History & Politics

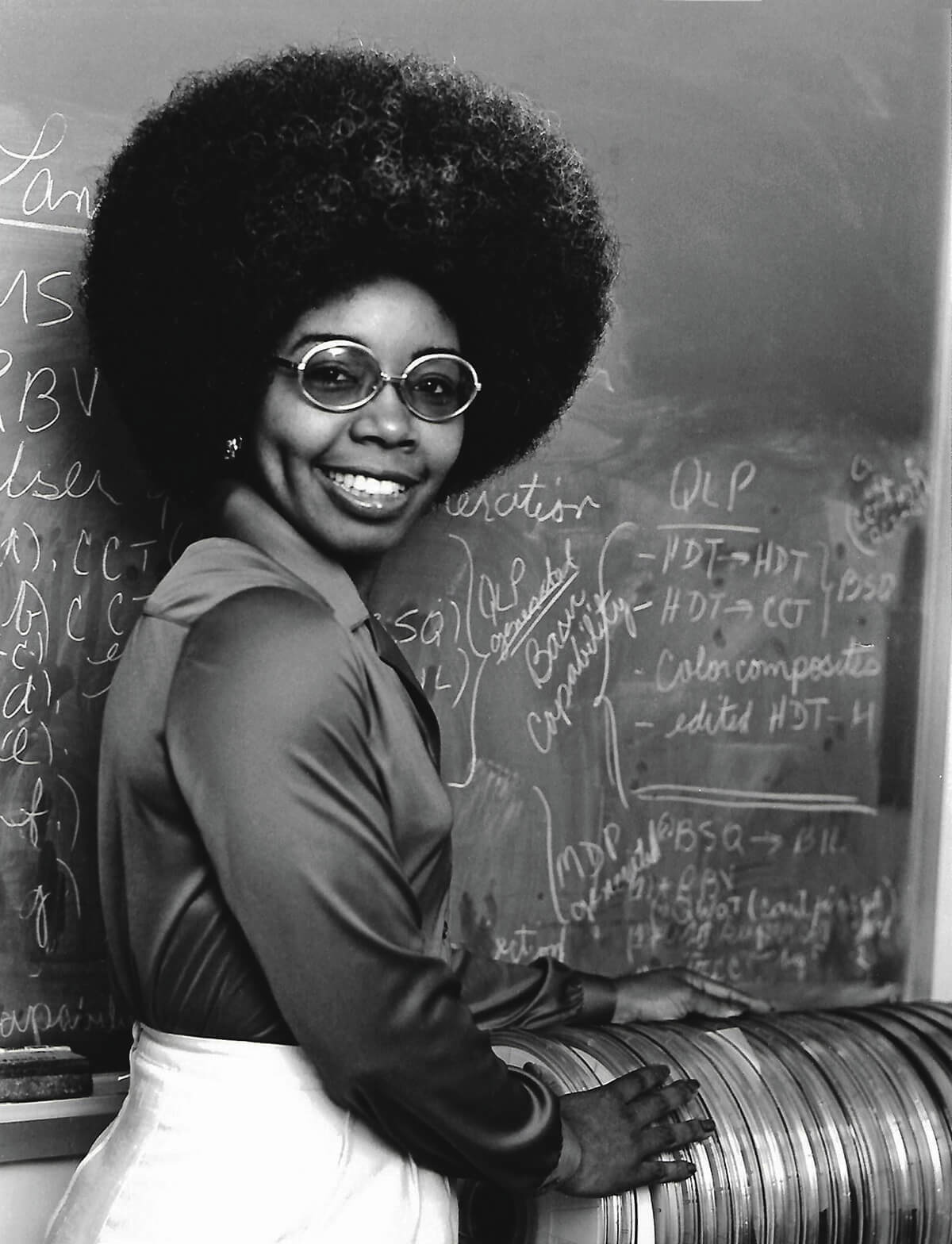

Baltimore Scientist Played Key Role in NASA’s Novel Satellite Imaging Program

NASA recruited Valerie Thomas from Morgan State in 1964.

Built to alleviate a housing shortage created by World War II workers and Black veterans flooding into the city, Cherry Hill did not yet have a branch of the Enoch Pratt Free Library when Valerie Thomas began school there. Nonetheless, she found something at the ad-hoc library set up at the community center that piqued her interest.

“The first book I brought home was The Boys’ First Book of Radio and Electronics,” she says. “It had illustrations of projects students could make and I showed it to my father, and he said, ‘Oh, I know how to do that, and that.’ He knew about electronics and also photography and even developed his own film, but he didn’t show me how to do anything.”

The next book she took out was The Boys’ Second Book of Radio and Electronics, and again her father did not offer to assist. “I got the message. Electronics is not for girls. ‘Go sew with your mother. Learn to do hair like your mother.’ I decided to master my sewing, which I did. I taught myself how to do hair.”

Thomas still wanted to know about science and technology, but it wasn’t until a senior year physics class at all-girls Western High School that she began learning about “what made things tick.”

The next year at Morgan State, the head of the physics department got her up to speed on trigonometry, which took all of 20 minutes, and she was on her way. Typically, the only woman in her upper-level science and math classes, she excelled. When NASA came for a recruiting visit in 1964, they offered her a job.

At NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center in Greenbelt, the now-79-year-old Thomas would become a leader and expert in the development of the agency’s Landsat program, which digitized some of the earliest satellite images of Earth. Thomas became renowned inside NASA for creating the key programs and documents that enabled researchers at NASA and around the world to visualize Earth and its ever-changing landscape from reams of computer tape data.

Fifty years after its launch, Landsat remains a one-of-a-kind resource for research into agriculture, geology, regional planning, natural disasters—and climate change. Landsat images are used to chart deforestation around the globe as well as receding glaciers. Not that it was smooth sailing at the start at NASA, where Thomas got to know Katherine Johnson and Mary Jackson, two of the women portrayed in Hidden Figures. Her first supervisor provided neither assignments nor guidance.

“There was an older Black woman, a scientist, who came by and she kept asking if he was giving me work,” Thomas says. “When his supervisors realized the situation, they moved me and my career took off like a rocket.”

Later, Thomas took every opportunity to talk with students and mentor interns, earned a doctorate, raised two sons, and became the first woman president of the National Technical Association, which focuses on helping African Americans progress in STEM fields.

A half-dozen years ago, Thomas began substitute teaching at DuVal High School in Prince George’s County, not far from Goddard. The magnet school specializes in science and technology.

“Word eventually got out about my time at NASA,” Thomas says with another chuckle. “Students would hear about my background, and then the ones who knew would tell other students when I’d get in front of a new class. They’d nudge them, ‘Google her, Google her.’”