History & Politics

Baltimore’s Ann Koger Smashed Tennis Barriers

Morgan grad was also the first woman to officiate a D-I men's college basketball game.

“My mother, Myrtle, was an avid tennis player and we lived near Druid Hill Park, so my three sisters and I grew up playing,” recalls Ann Koger. “She joined the Baltimore Tennis Club, whose history people should look up. They were doctors, lawyers, and educators who offered lessons and they put together a program to develop juniors and organized tournaments.”

In 1917, the club, originally called the Monumental City Tennis Club, hosted the first National Championship of the American Tennis Association, which remains the oldest Black sports association in the U.S. In 1924, the club again hosted the ATA National Championships in Druid Hill Park. In 1948, several club members, including Koger’s mother, protested the segregation of the park’s popular clay courts and, despite arrests, got the city to open the courts.

Eventually, the Baltimore Tennis Club played host to U.S. Open and Wimbledon champions Althea Gibson and Arthur Ashe—as well as Koger, who would go on to a groundbreaking career at then-Morgan College, where she starred on the men’s team, and as one of the first two Black women, with former Morgan teammate Bonnie Logan, to play on the Virginia Slims professional circuit. (Koger was on hand when Billie Jean King routed Bobby Riggs in the famed “Battle of the Sexes” match at the Houston Astrodome in 1973.)

Not that discrimination on Baltimore’s tennis courts had ended when she began playing as a girl in the late ’50s. Black players could only use Druid Hill Park’s clay courts after white players had first crack. At public-court tournaments, the Black players were all put into the same bracket to prevent more than one from reaching the finals. Other tournaments were held at private white clubs, which maintained the city’s only grass courts.

“The first time I played on grass was at a national tournament in Illinois,” Koger says. “To prepare for the speed, I practiced indoors on a basketball court.” Then, there was the cheating by some white opponents, which was ignored by officials. “I told one girl that I was going keep playing until I met her again, and I was going beat her,” Koger says. “She looked at me like I was a crazy. Being 12, I’d sit down under a tree and cry.”

After her pro career, Koger coached at Haverford College for 35 years, once pulling the team from a South Carolina event as part of a boycott around the state capitol’s Confederate flag. She also found time to officiate college basketball and was the first women to referee a Division I men’s game in the ’80s. Still, her time at Morgan, where she lettered in seven sports from 1968-1972—an era loaded with Baltimore talent—remains memorable for many reasons.

“I taught [future NBA first-round pick] Marvin Webster his hook shot,” she laughs. “In a pick-up game, I once got sandwiched under the boards between [future Pro Bowl tight end] Ray Chester and another football player and got knocked out.

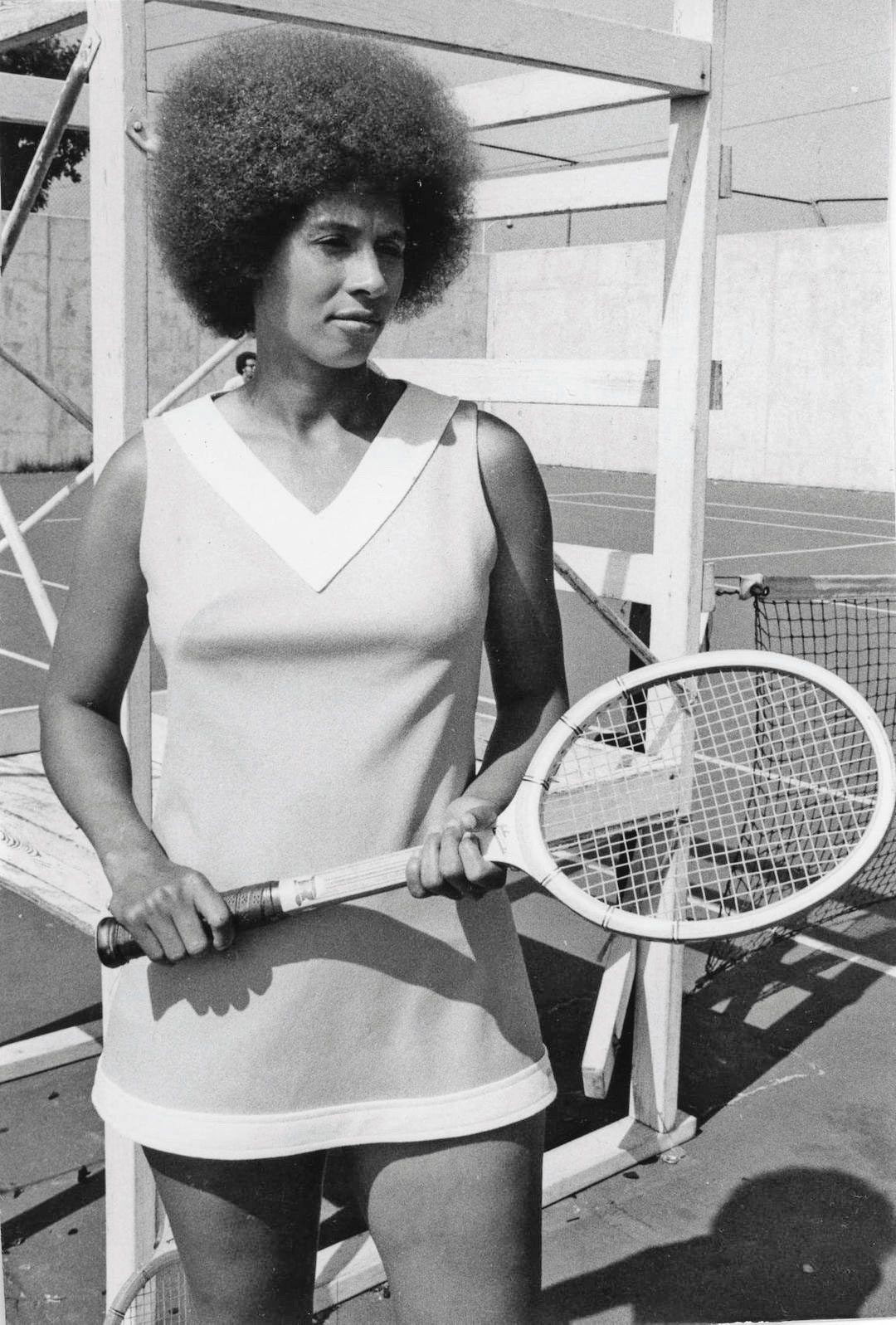

“Everyone always comments about my hair when they see those photos from Morgan,” Koger continues, with another laugh. “On campus, the police would stop me because they thought I was Angela Davis, who was then a fugitive wanted by the FBI. I don’t think I even look like Angela Davis. I did like the hairstyle. No fuss, which was perfect because I went from one sport to the next in those days.”

Not Angela Davis. But a revolutionary with a racquet.