History & Politics

The Story of the Baltimore Cat That Joined the Coast Guard During World War II

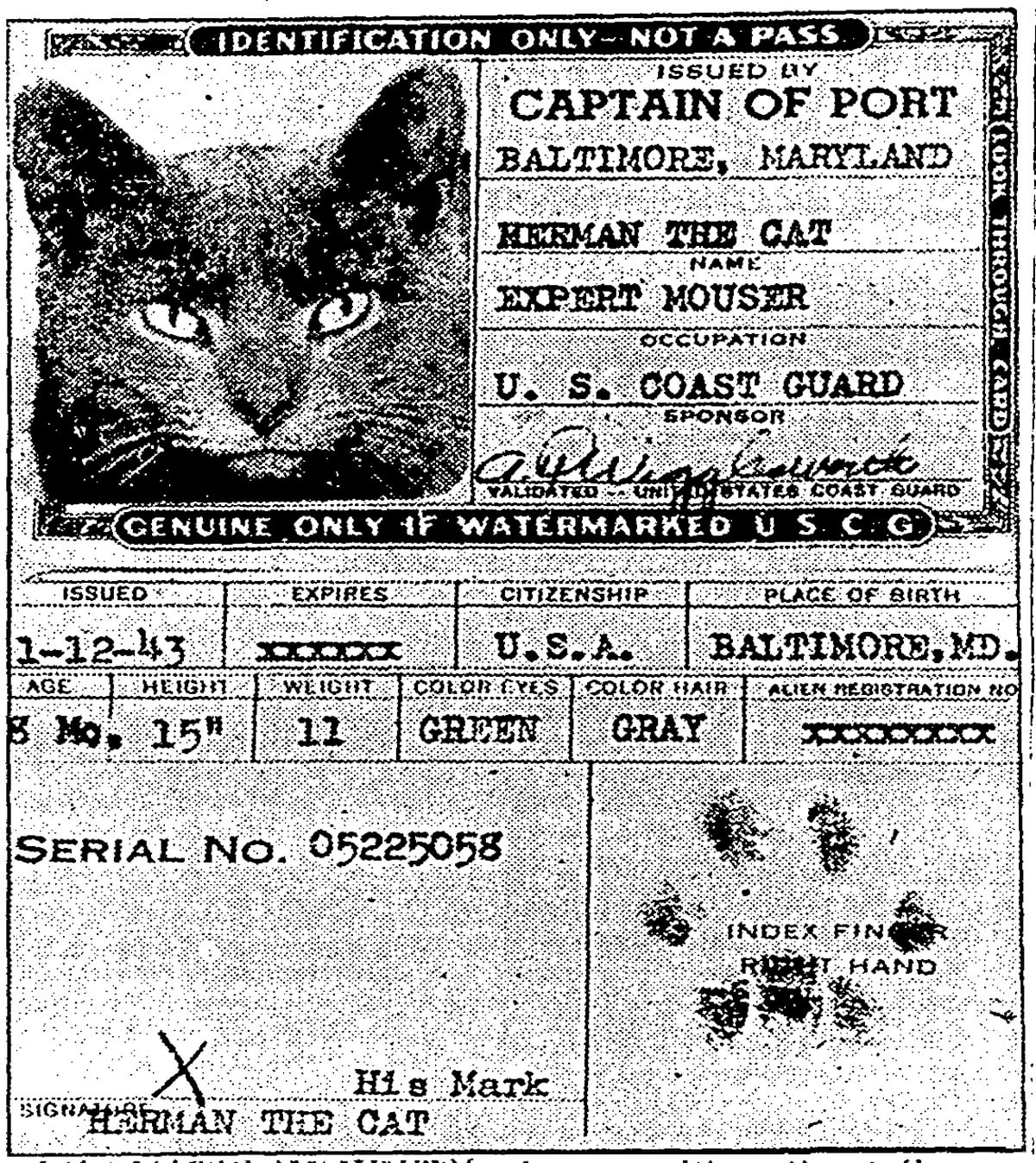

Before the Navy started restricting animals on ships, it issued an official port of Baltimore photo I.D. to Herman the Cat: Expert Mouser—a favored feline in service on its docks.

Concerns about rats carrying disease aboard ships, chewing through rope lines, and stealing provisions were quite serious during World War II at the busy port of Baltimore. While the city’s prolific brown and gray rats, in theory, helped prevent outbreaks of bubonic plague by killing any of the rare but disease-carrying black rats which could jump off a ship, their eradication remained important.

“It is a good thing to get rid of rats in general,” Col. Richard P. Strong, Medical Corps, United States Army, and a graduate from Johns Hopkins Medical School, told The Baltimore Sun in a January 1943 story. “They carry endemic typhus.”

It was with those ship-dwelling rats (and mice) in mind, and wartime precautions being what they were, that the U.S. Coast Guard that same month issued an official port of Baltimore photo identification to a favored feline in service on its docks.

Herman the Cat, occupation: EXPERT MOUSER, age: 8 months, height: 15 inches, weight: 11 pounds, eyes: GREEN, color hair: GRAY, received his credentials on Jan. 12, 1943. A pawprint substituted for the standard right-hand index fingerprint. (See above photo.)

“His is one of a select group issued a United States Coast Guard identification card,” The Sun reported in its weekly service edition. “No longer can anyone stop the mascot at Pier 4, Pratt Street, as he goes about molesting rats.”

Herman’s induction even made the popular Paramount newsreels of the era, which were distributed to theaters around the country.

Seamen and cats have a bond that dates back as long as people have been sailing. Ship cats have been deployed on merchant, exploration, and naval vessels ever since the ancient Egyptians, who venerated the whiskered creatures and kept them as live-in pets and brought them aboard Nile River boats to catch rodents and birds nesting in waterside thickets. It was from this work, sailing into various ports of call, that the species began to spread around the globe.

In addition to providing inexpensive disease prevention and companionship, cats were favored by superstitious sailors, who believed they brought good luck. Others thought the sight of cats fighting before departure spelled doom. Early sailors learned that a cat’s behavior—the twitching of its tale when agitated, for example—could indicate a drop in air pressure and that perhaps rough weather was ahead. Sailors also adopted cats from foreign destinations as mascots and reminders of their pets at home.

During World War I, the U.S. Navy banned alcohol onboard its vessels, but still allowed cats to boost safety and morale. Photos of mascot cats (and dogs) on U.S. Naval vessels appear as far back as 1888—and up through World War II—and show them playing with Navy fighter pilots before battle missions.

Hard to believe, given cats’ notoriously independent dispositions, but “Bounce,” the feline mascot of the USS Chicago in 1905, was trained to stand attention on his hind legs and salute with a paw whenever “The Star-Spangled Banner” was performed, according to the 2022 illustrated hardcover, Cats in the Navy.

Current Navy policy does not officially ban cats on ships, “but strict policies enacted in the 1950s due to quarantine laws and political criticism mean that permission to have an animal on a ship is rarely granted,” according to the Military Officers Association of America. (Fighting budget cuts in the 1950s, Navy leadership was embarrassed by Congress, who said they squandered resources, pointing to its cat funerals.) “One of the rare occasions is when an aircraft carrier changes home ports and transports sailors’ cars, dependents, and pets to their new location.”

For Herman, getting his identification was no easy matter. Like many defense workers, including some of the foreign-born, he ran into issues over his birth certificate. Nonetheless, Cmdr. C.H. Abel, captain of the Port of Baltimore, signed off, noting regulations at the time said nothing regarding cats. In addition to pursuing vermin, entertainment was listed as one of Herman’s duties. Rare for his kind, he was said to allow everyone to pet him.

“That’s it,” said Chief Boatswain A. M. Talbot, who was in charge of Pier 4 in 1943. “He’s an ambassador of good will, a diplomat.”