This story was published in partnership with The Trace, a nonprofit newsroom covering gun violence in America. Sign up for The Trace’s newsletters, here.

Ray Kelly worried that the sound system wasn’t going to work. If the speakers failed, he was less likely to draw people to the park to build support for Baltimore’s movement to defund the police—to shift law enforcement funding to other services and projects that proponents hope can decrease violence. If he couldn’t get their attention with music, Kelly worried, he wouldn’t be able to explain the opportunity they had to radically reimagine how to keep their communities safe.

“Music is what brings this community outside,” Kelly said. He fussed with the wires until R&B singer Miguel’s “Sure Thing” began to fill the park. Moments later, as Kelly predicted, the small trickle of residents who had wandered out of nearby buildings to see what was happening gave way to a flood of more than 200 people.

The more listeners the better, because the defund movement is at a crossroads in Baltimore and elsewhere. The country experienced a record homicide spike in 2020, with cities like New York and Los Angeles reporting historic year-over-year surges—still well below the record murder rates of the ‘80s and ‘90s, but enough to stoke fears nationwide. Political support for defunding law enforcement has withered in many places, the gains earned during the summer 2020 protests flagging as people worry cities cannot fight surging crime without police.

New York City voters picked Eric Adams, a former police officer and defund critic, in the Democratic mayoral primary in June, while the new president of the Los Angeles civilian oversight panel is an outspoken critic of the defund movement. Supporters in both cities are frustrated by the lack of sustained political support from government institutions, as across the country, defunders are still voicing their demands through demonstrations.

In Baltimore, defund proponents are embracing a longer play. Over a decade of activism focused on the city’s notorious police force, they’ve learned that effecting lasting change isn’t as simple as a single summer of outrage. Instead, they are pushing for gradual movement on the city budget and the slow toil of working through bureaucracy. These advocates hope to convince both their neighbors and their political representatives that the bold choice is the one that will keep them all safer.

But with the death toll of the city’s gun violence rising, residents in neighborhoods on the front lines of violence are caught between a police department with a record of abuse and the fear that even a marginal cut to funding will lead to chaos and even more violence. Defund leaves people with so many unknowns, making it a tough sell. That’s why Kelly, the local face of police reform activism, fussed with those speakers, trying to put people at ease with music before broaching the fraught subject.

It was the first Saturday in September, a few days after school started. Kelly had organized the block party on a thin slice of concrete and brick in Pennsylvania Triangle Park, across the street from St. Peter Claver Catholic Church in West Baltimore. There were backpacks for kids, hot dogs and hamburgers for enjoyment, church volunteers to wash people’s feet, and a nonprofit on hand to help residents to get old criminal cases expunged from their records. In the middle of the park was a burgundy tent emblazoned with the words “Citizens Policing Project.”

Four teenagers fanned out from the tent to ask residents to fill out a survey about their experiences with the Baltimore Police Department. The survey asked how officers treated them, how they thought the agency should change, and if they wanted it to be dismantled and started anew. They could also weigh in on alternatives: If they wanted to trim police staffing, how else might Baltimore make their neighborhoods safer?

Ready to Act

The movement Kelly was trying to grow had been in motion here long before George Floyd’s murder by a Minneapolis police officer in May 2020 propelled “defund” from a verb to a noun. In April 2015, 25-year-old Freddie Gray, from Baltimore’s Gilmor Homes public housing complex, was tackled to the ground by police officers, shackled by police, and subsequently thrown in the back of a BPD transport van. He died days later from injuries sustained during the arrest, sparking the largest uprising in Baltimore since the assassination of Martin Luther King, Jr., in 1968. The knife Gray was arrested for carrying turned out to not be illegal; the officers charged in his death were ultimately ruled not responsible.

It was a textbook example of what residents said was wrong with BPD: Police flooded a neighborhood in response to crime, arrested someone who hadn’t broken the law, physically abused him until he died in their custody—and were cleared of legal responsibility for his death.

In the wake of the uprising, what would become the Baltimore defund movement began to take shape. Kelly, already a local activist focused on the police department, had been surveying residents about their experiences with BPD hoping to prove that the agency needed to change. His peers had been lobbying the Maryland state legislature to reform policing, with moderate success.

The activists identified underlying social ills as the drivers of violence. Baltimore has long been plagued by disinvestment, white flight, and a decades-long industrial exodus. Its schools are underfunded, the housing stock is old, and according to the 2020 census, 1 in 5 residents lives in poverty.

So the calculus was easy, in Kelly’s estimates. Until the city spent more money providing jobs and addressing residents’ health, housing, and education needs, it could never be safe. With Baltimore spending more per capita on police than any other American city, it made sense to fund those things using money from the policing budget. Many defund advocates say the city’s safety should never have been the exclusive domain of police—a force designed, in their view, to protect property and react to crime—to begin with. They draw a line connecting public safety to economic stability, which allows a community to provide for its residents and, they hope, prevent them from turning to crime in the first place.

Baltimore Police Department Commissioner Michael Harrison remains skeptical. “In an environment where violent crime is higher than in other jurisdictions, maximizing the resources that are available to reduce violent crime is critically important,” Harrison said in an emailed statement. “It would be detrimental and catastrophic to reduce capacity.”

Just this Friday, Maryland’s governor had harsher words. “Trying to reduce crime by defunding police is a dangerous, radical, far-left lunacy,” Gov. Larry Hogan said at a mid-October press conference, in which he called Baltimore and its flirtations with the defund movement a “poster child for lawlessness.” Hogan announced a $150 million initiative to send more state funding to the police for hiring, equipment, salaries and training. “We can not defund the police,” Hogan said. “We need to refund the police.”

Maryland typically gives around $115 million in direct aid and grants to local law enforcement agencies across the state each year, including BPD. Hogan’s newest proposal would more than double the amount the state provides for those agencies in 2021 alone. The governor will need to get most of this spending approved by the General Assembly, which is run by Democrats—and routinely rejects his proposals.

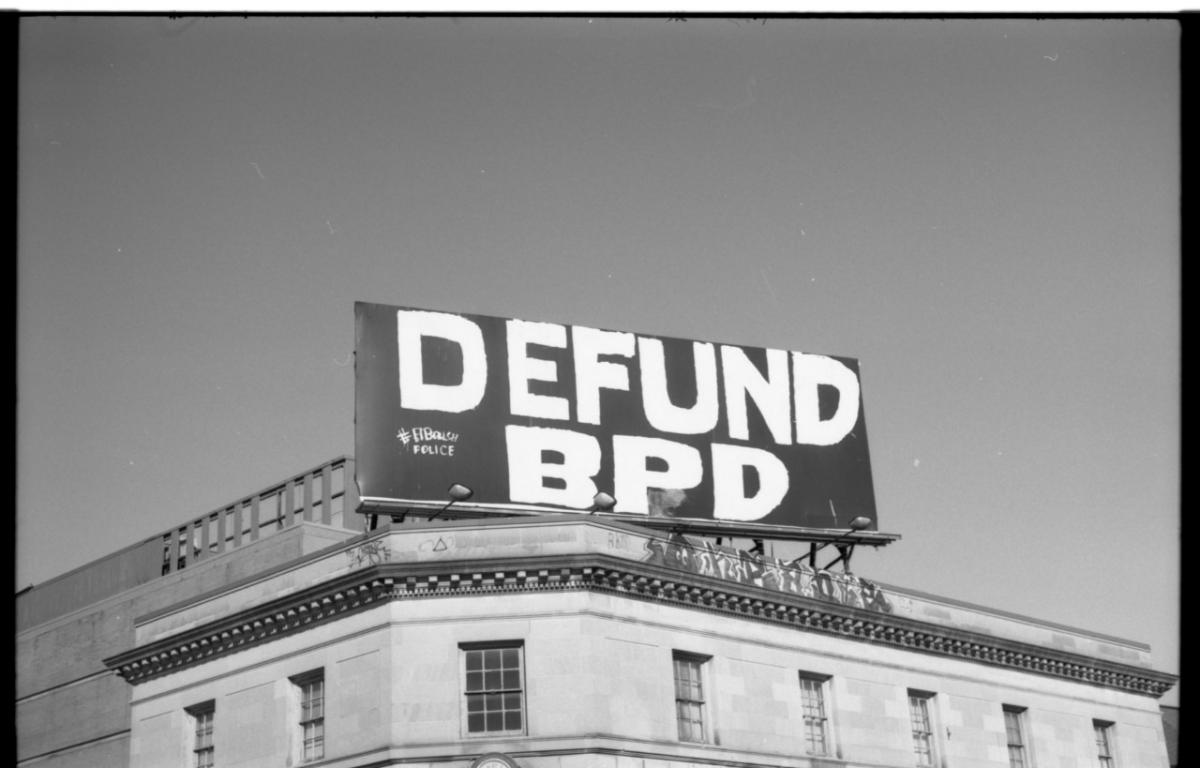

Because of the activists’ early work, when Floyd’s murder galvanized the defund movement across the country, Baltimore was primed to act. Residents painted “Defund the Police” outside City Hall and “Defund BPD” over a billboard above the busy intersection of North Charles Street and North Avenue. “The community is saying this ain’t working, and we need to cut the funding to the police department,” said Rob Ferrell, 35, a senior member of Organizing Black, a collection of young Black activists affiliated with the Movement for Black Lives.

Weeks later, Baltimore sheared $22 million from the once-sacrosanct police budget. But by the summer of 2021, the city had increased that budget by $28 million, restoring the cuts and then some.

“Part of this is about weaning ourselves off a system that centers police,” said Zeke Cohen, a Baltimore City Council member who voted in favor of the $22 million decrease in BPD funding before he supported this spring’s increase.

Harrison says that the police are not the long-term answer to reducing violence, but they are an important part of keeping it in check. “There is a need for non policing entities like social service providers from multiple disciplines to deal with the root causes of crime and provide pathways for individuals to move away from a life of crime,” Harrison said, “but again, not at the cost of reducing police capacity and eliminating positions.”

The changing politics around defund have led Kelly and his colleagues back to the grunt work of their early days: the unglamorous and tedious labor of passing out surveys and gathering resident testimony that could determine whether “defund the police” ever becomes a long-term reality. They hope the stories they collect will add a human element to their campaign to change policing across Baltimore, and perhaps across the country. Kelly and his cohort, who make up a broad coalition called the Campaign for Justice, Safety, and Jobs (CJSJ), have articulated at least one clear goal for the short run: They want the city to strip $100 million from the Baltimore Police Department’s $555 million budget over the next two years.

They realize they can’t be too prescriptive as they try to convince thousands of residents in crime-beleaguered neighborhoods that there are alternatives to the police. They’ll ask residents what they need, and they expect the answers to be complex. “The key is not to present the solution, because I don’t know the solution,” Kelly said. “It’s about taking the time to get the shit right.”

The Beginnings of a Movement

When they first began organizing, the groups that would eventually form CJSJ prioritized police reform at the state level. It took a decade of lobbying, but these early efforts did bear fruit. This spring, lawmakers agreed to overturn some police protections, such as the 10-day waiting period officers were granted between a shooting and their questioning. In the same session, lawmakers passed legislation allowing Baltimore residents to vote on returning full control of BPD to the city from the state, which has run the department since 1860.

The legislative victories are important, but Kelly has never basked in the glow of gains won in Annapolis. He is constantly checking up on his people back home in Baltimore. “Someone is always calling me because their boyfriend got locked up, or someone got killed and the mother calls me,” Kelly said.

Those calls come from a community Kelly has lived in for 52 years. In that time, he came to know many of its residents, including Antoin Quarles, a close friend who volunteered at Kelly’s September event in the park. “I used to be laid out in this park off smack [heroin],” Quarles said. The 49-year-old now runs a reentry assistance program called Helping Oppressed People Excel, HOPE for short. He spent more than two decades in prison, some of that time alongside Kelly, who landed at the Jessup Correctional Institution for distribution of narcotics in the early 1990s.

“I used to not be a nice guy,” Kelly said, pointing to the tattoos announcing his long-ago gang affiliation. After a few stints in prison, he would eventually return to his roots, if not his old habits. St. Peter Claver Catholic Church is one of the oldest Black Catholic congregations in the country; it’s two blocks from the street Kelly grew up on, and where he was baptized in 1973. It is now also the home of his work on policing.

In 2013, Kelly conducted his first survey on policing in West Baltimore, speaking with hundreds of people. He learned they wanted more foot patrols and also more meetings between community members and police. After some letter-writing and lobbying, the city met those demands.

The following year, Kelly was back at it, asking more community members what they wanted from the police. This time, West Baltimore residents accused officers of routinely dishing out beatings, ignoring crimes that occured in plain sight, and excessive stop-and-frisk searches in which residents were sometimes stripped naked. Then, the ground shifted.

What Does “Public Safety” Mean, Anyway?

Watching footage of the uprising after Freddie Gray’s death made organizer Ferrell, who was out of the country at the time, feel like he wasn’t doing enough. “It was like a weird out-of-body experience,” he said. “I should have been with my people.”

Ferrell returned to Baltimore and linked up with Ralikh Hayes, a 28-year-old veteran organizer. Hayes, Trè Murphy, and Michaela Brown wanted to create a grassroots organization focused on Black liberation, a space designed for young, vocal Black advocates. They established Organizing Black in 2016.

From their earliest days, different organizers had differing visions as to what “defund” actually meant. Should “defund the police” be interpreted in narrow and literal terms? This new wave of activists would push a much more radical agenda. Many in groups like Organizing Black see the police as defenders of property and the capitalist status quo. To them, the end of policing is a move toward a society that can truly wrestle with capitalism.

Others call it a reform movement intended to question and scrutinize every dime spent on police, limiting budgets to cover operational costs but not abolishing the system entirely. These different views have created a working tension within the broader coalition.

“Defund and divest aren’t enough; we need to work toward abolition,” Ferrell said.

For Kelly, abolition is not a realistic goal, especially given the prevalence of crime in the city. “When your grandmother gets knocked over the head coming home from the grocery store, you need the police,” he said.

In 2015, Kelly led more than 600 Baltimoreans through a peace march along Pennsylvania Avenue. At a drug corner, he asked a simple question: What did he need to do to get the guys on the corner off the street? The answer, they said: “$15 an hour plus benefits.”

But even as the uprising sparked a new wave of youth activism, the streets of Baltimore were turning increasingly, exceedingly violent. In May 2015, the month after Gray died, the city recorded 42 homicides, and July’s tally reached 45. It was the start of a six-year surge that has yet to abate.

Reform or Renewal?

In 2016, Kelly compiled the results of the surveys before and after Gray’s death into a report, titled “Over-Policed, Yet Underserved: The People’s Findings Regarding Police Misconduct in West Baltimore.” While the department maintained a strong visual presence in the neighborhood, the report said, it did little to stop crime and violence. Furthermore, police officers mistreated the city’s Black residents, targeted them for pedestrian and vehicular stops, and routinely violated their constitutional rights.

The U.S. Department of Justice released its own report in August 2016, documenting many of the same transgressions. The following January, the city entered into a federal consent decree, which forced the police department to stop using stop and frisk, train officers in de-escalation and how to better interact with people during mental health emergencies, and maintain staffing levels. Kelly was later appointed to the monitoring team.

As the city inched toward reforms, corruption among the Baltimore police ranks started coming to light. A few months after the consent decree agreement was signed, seven members of the Gun Trace Task Force, a specialized unit charged with removing guns from the streets, were accused and later convicted of racketeering, robbery, extortion, overtime fraud, and selling drugs seized during police operations. The officers were arresting dealers and illegally searching their homes to pilfer cash and drugs. The city paid more than $13 million to settle lawsuits related to the abuses.

Where Gray’s death was a clarion call to push for police reforms, the Gun Trace Task Force incident hardened the resolve of many activists, convincing them the department was in such disrepair that mere changes couldn’t fix it. Defunding the police, on the other hand, would at least limit its ability to commit further abuses. A defunded department could no longer pay for the military vehicles used against protesters in the uprising, or for specialized task forces that wielded their power to profit off those they were policing.

The Quiet Power of the Advocacy Class

In 2020, Kelly’s small office behind the auditorium of his church was abuzz. Baltimore was in the middle of a Democratic primary for the mayor’s seat. The leading candidates came to talk about their approach to policing. Kelly and the Campaign for Justice, Safety, and Jobs cannot formally endorse candidates, but they can cause trouble for those who refuse to give the coalition facetime or take positions it opposes.

When Brandon Scott, then City Council president, came to see Kelly in spring 2020 to seek support for a mayoral run, Kelly was moved by Scott’s commitment to a public health approach to violence. Scott had also promised to move money away from policing. CJSJ helped Scott’s team get people to the polls (COVID-19 had delayed voting by about a month) and worked a quiet grassroots campaign to get him elected.

They spent the weeks before Floyd’s murder discussing reducing the police budget with the campaign; Scott pushed for and won the $22 million reduction. Weeks later, he won the primary and cruised to a win in the general election.

After Scott took office, the court-appointed consent decree monitor, Judge James K. Bredar, issued a stern warning about the city stripping money from the police department. Since cutting the budget could have resulted in a fine—a consequence of being out of compliance with the consent decree—Scott balked at a second year of cuts. He also argued, as did Harrison, the police commissioner, that the department was already short on officers and couldn’t weather any reduction. So Scott gave the police more money, expanding the agency’s budget beyond the amount cut the year prior. At the same time, Kelly, feeling muzzled by his official role, left the consent decree monitoring team.

The Future of Defund

The political winds that favored defund in summer 2020 began blowing in the movement’s face by the following spring, but the Campaign for Justice, Safety, and Jobs remained committed to its original mission of moving money away from policing. The city was fresh off Scott’s decision to increase police funding, and the police commissioner announced plans to put more cops on the streets to address yet another spike in violence.

As mayor, Scott had morphed from an ally into what Ferrell called a target of the movement. Defund had to change as well. Activists realized they needed more city residents engaged in the budget process. “It’s important for folks to recognize how little power they have,” Organizing Black’s Hayes said. “Previous mayoral administrations have talked to community members about their budget priorities, and I don’t think it was done to gain input. They have done it largely to tamp down criticism.”

Baltimore might seem the least likely place to revive a defund the police campaign: The city is on pace for a seventh straight year of topping 300 homicides annually. But defund supporters don’t see those stats as an argument against their movement. If anything, the numbers show that no matter how large the police budget grows (currently it’s $900 per resident), the department has not been able to make Baltimore safer.

The campaign plans to educate people on pushing for participatory budgeting, a process through which the city would give Baltimoreans a hand in crafting the budget from scratch. The hope is that, over time, this strategy can shift money away from policing to other needs, as community members determine them.

It’s a risky move. “It could theoretically backfire,” said Hayes, whose organization supports abolition. “If there is a community that wants more police, I am actually okay with that. Having communities decide what they want for themselves is better than a theoretically pure push to defund the police.”

Over the course of the summer, through community events like cookouts, food drives, and block parties, Kelly and CJSJ continued to collect stories about Baltimoreans’ interactions with the police. All told, they’ve recorded more than 1,000 accounts, and canvassing will continue through the fall. Collectively, the responses add up to a testimony of life in the heavily policed neighborhoods of East and West Baltimore, mostly Black precincts that make up more than half the city.

Kelly has become accustomed to the police coming to his events, whether they are invited or not, and the block party across from the church in September was no different. Across the street, a half-dozen officers kept watch.

Walter Myles, a 61-year-old Black Baltimorean, was on his way to a book signing when the smell of sizzling hot dogs drew him to the park. He was one of a handful who filled out the survey that day. “Every time I’ve been stopped and felt a little intimidated, for the most part, it’s white police officers,” he said.

Rodney Hudson, a 52-year-old pastor at Ames Memorial United Methodist Church and a one-time City Council candidate who received the police union’s endorsement, moved to the city in 2007. Hudson, who is also Black, said his first interaction with Baltimore police was not pleasant. “The police stopped me one time and had me sit on the corner, right on the curb,” Hudson said. “They had no idea that I was a pastor at a church here.”

Stories like these are common in the city. According to publicly available data, Baltimore has spent more than $36 million to settle police misconduct cases since 2010. Still, neither man was convinced to join the defund movement, saying they believed the department could successfully be reformed. “I don’t support ‘defund the police’ now that I know exactly what it means,” Myles said. “If anything, we need more police.”

Organizing residents in the poorest sections of the city, where the violence is most acute, won’t get any easier. At a canvassing event in August, a young woman filled out the survey and agreed to share her story with the media, but changed her mind when volunteers told her she’d need to publish her full name. She quickly left the venue. “They are scared,” said Donna Brown, 52, and a co-founder of the Citizen Policing Project’s cofounder. “They are scared the cops are going to read this and possibly retaliate.”