History & Politics

A century and a half ago, Locust Point—Baltimore's Ellis Island—opened its historic piers to the foreigners who built the city's port neighborhoods. Today's newcomers face the same, and new, hardships.

All names in the first paragraph were changed throughout the story to protect the individual and/or family.

ALEJANDRO GARCIA’S FAMILY IN THEIR BALTIMORE HOME.

Morning of November, Alejandro Garcia took his two kids to their Highlandtown elementary school, said goodbye to each, and promised he would be back at the end of the day to pick them up. He told their mother, Anna, that he’d see her soon and hustled to his U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement’s appointment. He arrived a half-hour early, as was his practice. Garcia’s biannual check-ins at the ICE field office at Hopkins Plaza had become routine through the years, like a visit to the dentist’s office—some paperwork, a wait, an exam, a few questions, and then see you in six months. Still, his sister Maria was nervous each time her undocumented older brother had to report. “Stressful,” she says. “A family friend—Zoe—who has legal status, always went with him.”

Expecting the usual bureaucratic delays, he requested the day off from his employer, which was also his practice. The 36-year-old Guatemala native had been in the U.S. for 13 years, paid federal taxes, and had no criminal record. His son and daughter, American citizens by birth, were thriving in school, and he supported them and their mother, an active member of the community who is also legally blind.

He has not seen his family since.

“At lunch time, Zoe called me and said she hadn’t heard anything from Alejandro in hours and was scared. She thought something was wrong,” the 29-year-old Maria recounts several weeks afterward. As she talks she fills up with emotion. “I’m sorry,” she apologizes, pausing to wipe the corners of her eyes. “I told Anna it was probably nothing. I’m sure everything will be okay and that it was only taking longer than normal. Then, at about 2:30, she comes to my workplace, very upset, in tears. The immigration office finally told her they would not be releasing my brother today. At 7 p.m., we got a call from him from a jail in Snow Hill, and he said they were deporting him.”

Garcia, his children’s mother says, cried long and hard on the phone to her that night, concerned about what would happen to his 4-year-old daughter and 11-year-old son. “He wanted to be their hero. He kept saying he had let them down.”

From Snow Hill in Worcester County, Garcia was sent to a jail in Louisiana before the family could make arrangements to see him. Three weeks after his initial detention, the day before Thanksgiving, he was on a plane to Guatemala City.

Garcia cried long and hard on the phone to her, concerned about what would happen to his daughter and son. “He wanted to be their hero. He kept saying he had let them down.”

Maria, checking on her nephew and niece and their mother after church on a recent weekend, says she is more worried than ever about her own family. Sitting on a sofa in their tidy living room, she recounts crossing the U.S. border with an aunt at 15, and going to work right away as a housekeeper and babysitter. Her daughters—an 11-year-old and a 12-year-old who wants to become a doctor—are American citizens, but she does not have legal status, having only applied to the Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals (DACA) program last year. Her husband, a construction worker, is an undocumented immigrant from Mexico.

Since the Trump Administration ramped up interior deportations a year ago, the anxiety level in the Hispanic enclave of Southeast Baltimore, where most immigrant families are of mixed status, has become palpable. Last February, a nationwide weekend of ICE raids included the arrests of a popular Honduran barber and an established Ecuadorian business owner, leading to a pro-immigrant rally and march through Highlandtown. A few weeks later, another immigrant father without a criminal record was picked up by ICE officers and deported after dropping off his 9-year-old son at school. Over the summer, more than 30 employees at The BoatHouse Canton, a waterfront restaurant, left in fear after a Homeland Security official hand-delivered a letter demanding documentation of their immigration status.

Catalina Rodríguez Lima, director of the Mayor’s Office of Immigrant and Multicultural Affairs, says more than 100 local immigrant families have contacted her office seeking assistance after immigration arrests.

“I live day to day,” Maria says of her own potential deportation. “I try not to think about it.”

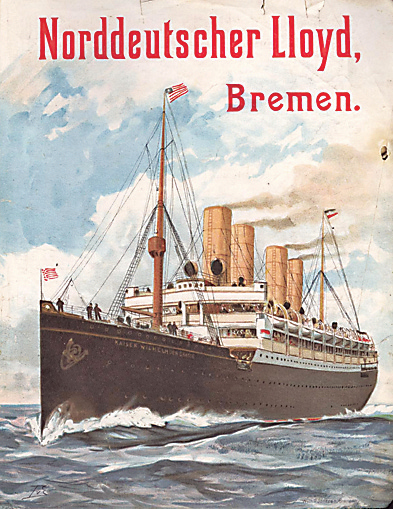

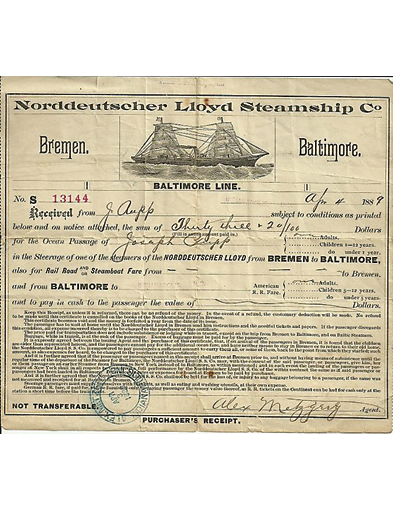

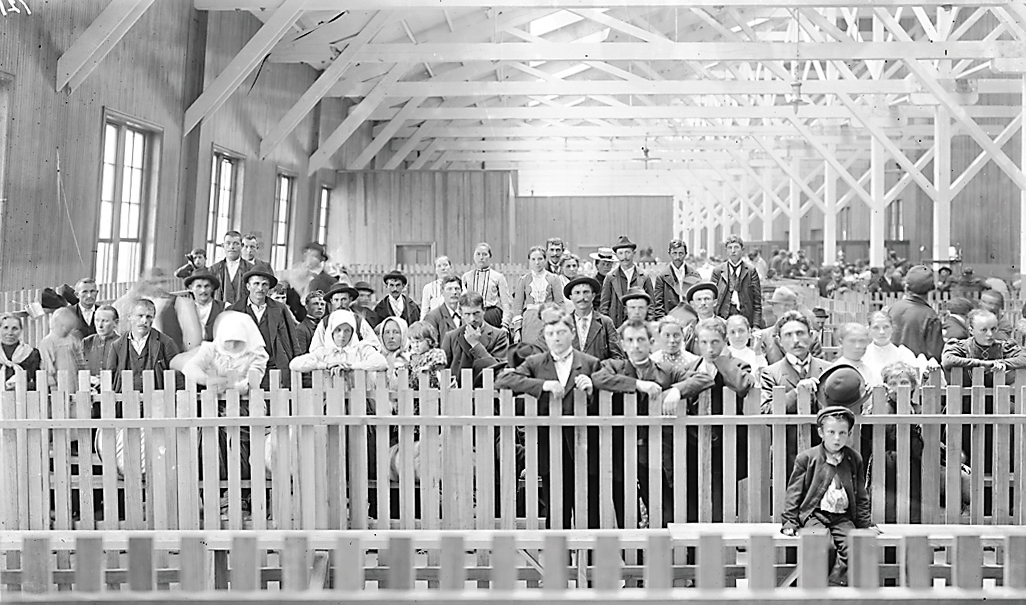

Locust Point immigration pier No. 9 built by the B&O Railroad. Immigrants arriving at Locust Point’s immigration piers in the early 1900s courtesy of the MARYLAND HISTORICAL SOCIETY. ADVERTISING PAGE FOR THE norddeutscher Lloyd, Bremen SHIPPING LINE; IMMIGRANT STEAMSHIP TICKET FROM 1889.

One hundred and fifty years ago next month, the arrival of the first foreign steamship—appropriately named the “Baltimore”—at the new immigrantion piers at Locust Point was greeted with a canon salute as it passed Fort McHenry and a parade down Broadway. Over the next five decades, the steady flow of Norddeutscher Lloyd ships from Bremen would re-chart the city’s course and character. From the opening of the Locust Point piers in 1868 until they closed in 1914—the period between the end of the Civil War and the start of World War I—1.2 million European immigrants entered Baltimore’s Ellis Island, making the city the third busiest port of entry in the U.S. and the busiest below the Mason-Dixon line.

“To understand the development of Baltimore,” says local historian Wayne Schaumburg, “you have to know about those piers and the influx of immigrants there who built the city’s ethnic neighborhoods around the harbor.”

Baltimore’s burgeoning B&O Railroad had privately funded and built the new immigration piers as it looked to fill passenger trains branching out into the unsettled Midwest. The railroad, the first commercial carrier in the U.S., inked a groundbreaking deal—put together by an immigrant businessman from Bremen named Albert Schumacher who sat on the B&O board—with the North German Lloyd line. After the 1890s, the vast majority of immigrants arriving at Locust Point would travel directly to a destination further west—in some cases to land bought sight unseen in Ohio, Missouri, Indiana, and Illinois. But the rest, often poorer Central and Eastern Europeans, carrying on average just $15—or 10 days wages—never ventured far from Locust Point. Often, they ferried over to Fells Point, Canton, and Highlandtown and headed into the city’s booming canning, garment, shipbuilding, steel, rail, and manufacturing industries.

Many of the struggles that the city’s current wave of working-class immigrants from Mexico and Central America encounter would have been familiar to these earlier Baltimore immigrants. They confront similar language and cultural barriers, stereotypes and discrimination, low wages—exploitation by employers and politicians—and backlash from entrenched, previous immigrant ethnic groups. In other ways—the increased criminalization of their presence, the aggressive deportation campaigns, the willingness to separate parents from their children, such as with the Garcia family, and the harsh anti-immigrant rhetoric from the president—their circumstances are unprecedented.

It is a coincidence, and a revealing one, that the latest epoch in Baltimore’s immigration saga is literally taking place on the same streets, in the same rowhouses as the past two centuries of history in Highlandtown and other parts of Southeast Baltimore.

One thing: It is important to keep in mind that the story of European immigration is not meant to serve as a complete history of Baltimore, nor its identity. The Great Migration—the broad movement of African Americans leaving the South for the North—takes place, for the most part, after the largest waves of immigration to the city. It’s worth noting that blacks fleeing the South left for many of the same push/pull reasons immigrants did—economic opportunity, full citizenship, freedom from persecution, and hopes of a better education for their children.

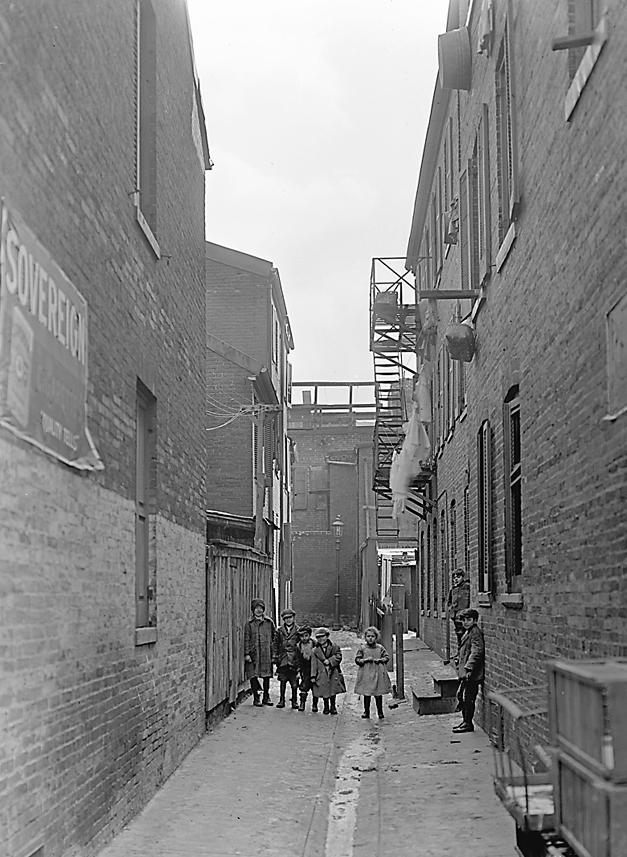

young boy carries loads of cans at a food packing plant in Baltimore, 1909. children at play in an alley near fayette street circa 1905 courtesy of maryland state archives

The first immigrants who arrived at the Locust Point immigration piers on March 23, 1868 were German, following in the footsteps of earlier, German immigrants to Baltimore—think the grandparents of Babe Ruth and H.L. Mencken—and The Great Hunger-plagued Irish.

That it was more Germans who initially came after the construction of the Locust Point immigration piers was hardly surprising, given that the agreement negotiated with Bremen essentially amounted to an exchange of Southern Maryland tobacco and Western Maryland coal for warm bodies. Not only was the B&O trying to book immigrants to expand their rail business, the state was looking to pitch the arable land it had for sale to Germans with cash to invest. Failing that, elected officials and business leaders were happy to bring more cheap labor ashore to boost Baltimore’s population and quickly industrializing economy.

The failed 1848-49 German revolution—the country was then a collection of confederate states—combined with feudalism, conscription, oppression, and their own potato famine had convinced hundreds of thousands of Germans that emigrating to the new democracy of the U.S. was worth a shot. America and Baltimore at the time also became a haven for Jewish Germans fleeing anti-semitic laws: The number of European Jews living in Baltimore rose from 120 in 1820 to an estimated 7,000 by the onset of the Civil War, including a certain Moses Hutzler, whose son Abram opened the iconic Howard Street department store. (Later, German Jewish entrepreneurs founded Hochschild Kohn’s, Hamburger’s, and Hecht’s.)

German Jews of the period also built the renowned Lloyd Street Synagogue, the third-oldest standing synagogue in the U.S., and now part of the Jewish Museum of Maryland in Southeast Baltimore.

Jewish immigrant hirsche lebe blume and his family in baltimore, circa 1870 courtesy of The Jewish Museum of Maryland.

In fact, so many native German speakers eventually came to Baltimore that, in the decades wrapping around the turn of the century, city council ordinances were legally bound to be printed in at least one of the local German-language newspapers. Remarkably, bilingual German-English schools served some 7,000 immigrant kids, who likely only heard Deutsch at home, at their peak in 1900. (Shaumburg says that his maternal grandmother, who landed at Locust Point, “refused” to learn English.) The major German newspaper in town, the Der Deutsche Correspondent, became a daily in 1848, and before the end of the century another dozen German-language newspapers had hit the presses in the city. Given today’s tenuous newspaper landscape—not to mention the hostility sometimes directed at immigrants who need time to learn English—it is noteworthy that the Deutsche Correspondent was published for three-quarters of a century here.

The other dominant immigrant group flooding into pre-Civil War Baltimore was refugees from food shortages almost beyond modern comprehension. As early as the fall of 1845, The Baltimore Sun reported the “most dreadful of calamities” under the headline “FAMINE IN IRELAND.” In a country of 8.5 million, more than 1 million people would die of starvation and famine-related diseases because of potato crop failures and indifferent British policies. Another 1.5 million Irish fled to America.

More than a few of these desperate, illiterate immigrants arrived on the banks of Fells Point—the point of entry before Locust Point—near death, according to contemporaneous accounts. Others did not survive the month-long journey aboard what became known as “coffin ships.” Baltimore’s Hiberian Society, which was founded in 1803 and still organizes the city’s St. Patrick’s Day parade, assisted many of the refugees.

Of those who did make it to Baltimore, many ended up employed by B&O, doing the backbreaking, dangerous work of digging tunnels and building bridges, or toiling at one of the nascent industry’s depots or Pigtown warehouses, like the one behind the right-field fence at Camden Yards. Underscoring their low socioeconomic standing, Irish workers often labored alongside free blacks. Indeed, the 1848-built rowhouse of immigrants James and Sarah Feeley and their six kids, which serves as home to the Irish Railroad Workers Museum, sits one block from the B&O Railroad Museum.

Accordingly, most of the first immigrant churches around the harbor were German and Irish places of worship. Holy Cross parish, founded in 1858 in Federal Hill, was the first faith community established in South Baltimore, servicing the religious needs for the some 1,000 Catholics of German descent living in the then-rising neighborhood. In neighboring Locust Point, Irish immigrants begat Our Lady of Good Counsel. A few years later, the cornerstone of the St. Mary, Star of the Sea church in Federal Hill—then just “the Hill”—was laid in 1869. Father Gibbons, later Cardinal Gibbons, the first Irish pastor in Locust Point, also served as pastor at St. Brigid Parish in Canton, rowing a skiff across the harbor in his priestly cassock and collar each Sunday morning, pulling double duty.

Tellingly, two German and Irish immigrant churches, Sacred Heart of Jesus—aka “Highlandtown’s Cathedral”—and St. Patrick’s serve almost exclusively Latino congregations today and offer Sunday Mass in Spanish.

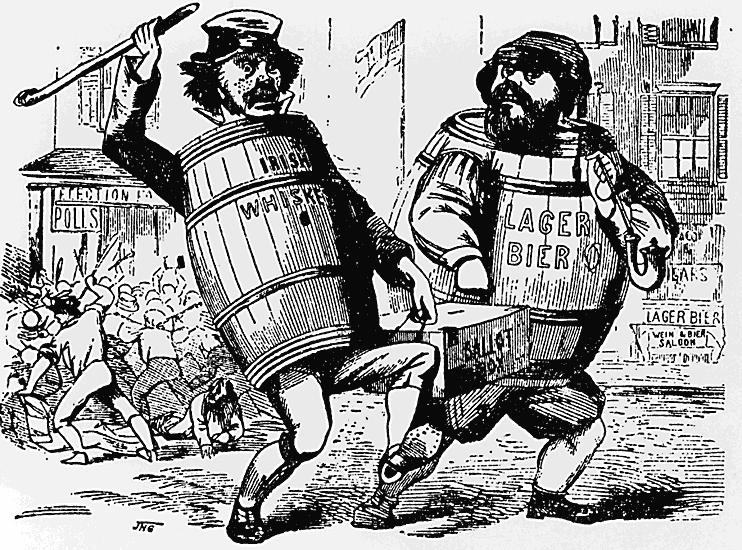

Cartoon charging Irish and German immigrants with stealing elections.

Then, as now, the immigrants and refugees of mid-century America dealt with powerful nativist forces, as surviving “No Irish Need Apply” signs attest. (Former Gov. Martin O’Malley kept one in his Annapolis office.) Not as well remembered is the virulent anti-immigrant Know-Nothing party, officially the American Party, which at its height in the 1850s, “included more than 100 elected congressmen, eight governors, a controlling share of half a dozen state legislatures from Massachusetts to California, and thousands of local politicians,” according to a recent Smithsonian tally.

From their hatred of foreigners to their Papal extremist theories, the Know-Nothings (so called because their first meetings were held in secret and if asked what they were up to, members were told to respond, “I know nothing”) sprung from a political movement that viewed Catholics as a “Romanist” threat to the nation, blamed German and Irish immigrants for driving up poverty and crime rates, and opposed the women’s right to vote. In their platform, the Know-Nothings said they aimed at restoring their vision of what America should look like with patriotism, Protestantism, self-reliance, temperance, and “a radical revision and modification of the laws regulating immigration, and the settlement of immigrants.” Specifically, they wanted to push the residency requirement for citizenship from five years to 21 years.

The blood Tubs were literally a group of butchers. “They dunked the heads of recalcitrant democratic party voters in tubs of animal blood they had collected. it was like gangs of New york.”

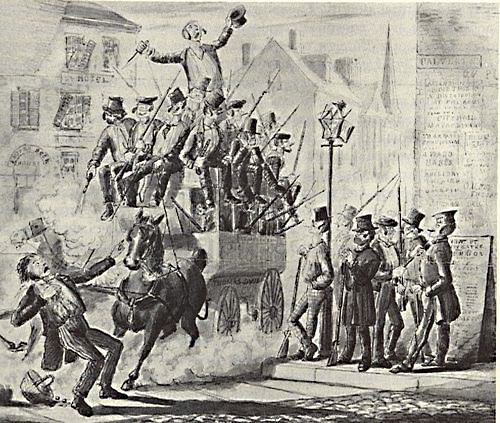

cartoon depicting A plug ugly election riot in baltimore in 1856.

Elections everywhere were brutal and crooked leading up to the Civil War, but perhaps nowhere more so than in Baltimore, which earned its moniker Mobtown from the intimidation, riots, and murder that accompanied its elections. Native-born residents, feeling less secure in their status, flocked to the emerging Know-Nothings, whose slogan—“America for the Americans”—was a full-throated reaction to the political influence and rising tide of immigrants. During the 1850s, thuggish political clubs in Baltimore, with names like Plug Uglies, Rip Raps, Rough Skins, Regulators, and Blood Tubs, surfaced in swinging response to the city’s unprecedented influx of immigrants. “The Blood Tubs were literally a group of butchers,” says local historian Nick Fessenden, co-founder of Locust Point’s Immigration Museum, which opened in 2016. “They dunked the heads of recalcitrant Democratic Party voters in tubs of animal blood that they had collected. It was like Gangs of New York.”

These Irish and Germans, escaping hunger and unrest, had become the country’s first urban immigrants and, between 1830 and 1860, they pushed Baltimore’s population from 80,620 to 212,418. Nearly 25 percent of the city was foreign-born—roughly three-and-a-half times the percent today.

know-nothing party flag from the mid-1850s courtesy of the maryland historical history society.

With the bloody backing of the criminal nativist gangs, Know-Nothing candidates held the mayor’s office for several years, captured a majority of the Baltimore City Council and, in 1857, won the governor’s office and the majority of the state house of delegates.

“The newcomers were often desperately poor. Worse still, from a native perspective, many were Roman Catholic,” writes Martin Ford, a former Towson University professor and retired assistant director at the Maryland Office for Refugees and Asylees, in a 2008 National Endowment for the Humanities article. “The Irish, in particular, were seen as drunken, belligerent foot soldiers of a corrupt Pope who had political designs on North America.”

brotman meat market and poultry on lomboard street, 1923 courtesy of The Jewish Museum of Maryland.

Immigration then came to a near standstill during “the War between the States.” It was not until the 1880s that Poles, Lithuanians, Slovaks, Bohemians, Russians, Ukrainians, and Eastern-European Jews boarded the North German Lloyd line ships for Locust Point.

From 1860 to 1890, the city’s population more than doubled once again.

The majority of the Polish immigrants arriving at Locust Point were Roman Catholics. Their first parish, St. Stanislaus, formed in 1880 in Fells Point and was served by Polish priests for decades before closing, to great heartache, in 2000. Holy Rosary Church, with its 3,000-pipe organ and 49-ton marble altars, followed St. Stan’s in Fells Point and then St. Casimir, with its twin, 110-foot bell towers, in Canton. Polonia, the city’s first Polish-language newspaper, began publishing in 1891. Poles, including women, and often children, working in the nearby canneries and picking fruit and vegetables in the summer in Baltimore and Anne Arundel counties, were becoming the backbone of Baltimore’s laboring class. Some 23,000 Polish-Americans were already living in the city by 1893, including the corner bakery-owning grandparents of former U.S. Sen. Barbara Mikulski.

Like the earlier German immigrants, the new immigrants from Eastern Europe were pushed by economic hardship, fear of conscription, class discrimination, and in the case of Jewish people, continued pogroms in Europe. Meanwhile, steamships, replacing sailing vessels, made the North Atlantic treks smoother and safer.

polish home club in upper fells point.

The Mikulskis are far from the only prominent local family to trace their history through Locust Point.

A partial list of Baltimoreans and their descendants with Locust Point immigration connections reads like a “Who’s Who” of Baltimore, and notably, Jewish Baltimore: Meyer Cardin, the son of Russian Jewish immigrants, served in the state legislature, sat on the city’s top court, and was the father of current Maryland U.S. Sen. Benjamin Cardin; the Cone sisters, Claribel and Etta, whose collection of French Impressionist and Post-Impressionist art is the prize of the Baltimore Museum of Art, were the children of German immigrant Jews from Bavaria; businessman and philanthropist Joseph Meyerhoff, whose name sits atop Baltimore’s Symphony Hall, was born in the Ukraine and came to Baltimore with his parents in 1906; Carroll Rosenbloom, who owned the Baltimore Colts, was the son of Russian Jewish immigrants; the descendants of Charles and Sarah Hoffberger, who arrived from the Austro-Hungarian Empire in 1881, first built a heating and oil business and then went on to own the National Brewing Company and the Baltimore Orioles; Zanvyl Krieger was one of eight children born to Austrian Jewish immigrants and, in 1992, his foundation donated $50 million to the Johns Hopkins University School of Arts and Sciences; Abel Wolman, who led American and international efforts to purify drinking water, was one of six children of Polish Jewish immigrant parents.

The Baltimore garment industry labor movement was, in large part, led by a Jewish immigrant named Jacob Edelman, who immigrated from Russia in 1912.

ikaros restaurant in greektown. Polish Treasures in Upper Fells Point.

Jong Kak Restaurant.

Frustrated and upset by the low wages and working conditions in Baltimore’s sweatshops—of which there were some 400 in the early 1900s, largely in the three-story, multi-generational rowhomes of Upper Fells Point—Edelman had joined his first strike a year after arriving in the city. He later earned a night school law degree, which he put to work in support of union and civil rights causes, eventually winning a seat on the Baltimore City Council. Edelman was not a typical Russian Jewish immigrant of the period; he arrived with more education than most, but he remained a champion of union and civil rights his whole life, including supporting an unsuccessful anti-discrimination bill (aimed at promoting the rights of blacks) in the City Council in 1958, whose defeat he said would make Baltimore “appear to the world as a bigoted hamlet instead of a great city.”

But the immigrant who made the most profound impact was a German tinkerer named Ottmar Mergenthaler, who came to the U.S. looking to join the industrial revolution and possibly dodge conscription into Otto von Bismarck’s army. His invention in Baltimore, the linotype machine, is credited with dramatically raising literacy rates across a single generation—Thomas Edison called it “the eighth wonder of the world.” His printing machines remain as centerpieces at the Baltimore Museum of Industry.

Italians and Greeks came, too, first forming Little Italy, and later Greektown. They generally came by train, often from New York, because there was no direct steamship service from the South Mediterranean region to Baltimore. Indeed, the former President Street train station, now a Civil War museum, is located across the street from the traditional Little Italy boundary.

By 1920, native Italian-speaking immigrants, who numbered 8,000, trailed only native German-, Polish-, and Yiddish-speaking immigrants in Baltimore.

st. leo’s church in little italy.

door in little italy.

In truth, two “Little Italy” neighborhoods formed in Southeast Baltimore. The first community grew around St. Leo the Great Roman Catholic Church. The second was established in nearby Highlandtown around Our Lady of Pompei, which was built in the early 1920s.

By 1940, more than 18,000 Baltimoreans were Italian immigrants or their descendents.

Thomas D’Alesandro Jr., mayor of Baltimore from 1947-1959, descended from these Italian immigrants. His daughter, Nancy Pelosi, whose mother was an immigrant, would become the first woman to hold the title of Speaker of the House.

Of course, John Paterakis, the deceased founder of H&S Bakery and Harbor East developer, and Peter Angelos, the current owner of the Orioles—two men who have profoundly shaped Baltimore—descended from Highlandtown Greek immigrant families.

Take a walk down Eastern Avenue and the vestiges are there—the Kaytn Memorial, delivered from Poland, in Harbor East, the Polish Home Club in Fells Point, bocce ball in Little Italy, the corned beef sandwiches at Atman’s Deli, the painted screen folk art created by Czech immigrant William Octavec, the golden domes atop St. Michael the Archangel Ukrainian Catholic Church, Hoehn’s German bakery, DiPasquale’s market, Mr. Boh of National Bohemian beer fame in lights atop Brewer’s Hill, and, Zorba’s, Samos, Ikaros, and the restaurants of Greektown.

One further, less obvious, Baltimore cultural note: The Patterson Bowling Center, the oldest duckpin lanes in the country, was opened by a Polish stevedore.

All of these institutions are now mashed up with Mexican and Central-American immigration outposts along Eastern Avenue—Tortilleria Sinaloa, Cinco de Mayo grocery, Miguel’s Barber Shop, and on and on.

“ten to 15 years ago, there were maybe three latino barbershops in baltimore," says serbando fernandez, “now, there are 40 barbershops.”

sErbando fernandez in his barbershop in highlandtown.

“Ten to 15 years ago, there were maybe three Latino barbershops in Baltimore,” says Serbando Fernandez, the Honduran immigrant barber who was picked up by ICE officers last year. “Now,” he adds with a smile and hint of exaggeration, “there are 40 barbershops.” Fernandez, who fled gang violence in his native country, also co-manages a youth bike repair clinic in Highlandtown, teaching kids how to fix their bicycles and giving bikes to kids who show up regularly. He was profiled by ICE agents, who apparently ran his legal Maryland license plate and driver’s license against its federal database after he entered a Walgreens on an otherwise quiet Thursday night. He eventually won legal status with the assistance of lawyers and activists.

latino mural in highlandtown.

“refugees are welcome here” poster.

In December, Attorney General Jeff Sessions came to Baltimore promising to further speed the deportation of immigrants and administration polices aimed at curbing overall immigration. Sessions announced a plan to hire another 60 immigration judges over the next six months.

In the first 100 days after President Trump took office, ICE already reported a nearly 40 percent increase in arrests over the same period last year. Those figures included a significant jump in the number of immigrants—nearly 11,000—who did not have criminal conviction, a 150 percent bump over the same period in 2016.

Sessions added that he supports the president’s proposals to end chain migration—the opportunity for U.S. citizens to sponsor family members for permanent resident status—and to prioritize the applications of immigrants who speak English or are highly skilled.

The former Alabama senator focused much of his attention on the DOJ’s partnership with Homeland Security and joint efforts to crack down on MS-13, an El Salvador-based gang. What wasn’t made clear was why Sessions chose Baltimore as the backdrop for his remarks. The gang is not prominent in the city, according to Baltimore police officials, yet Sessions highlighted Baltimore’s violent crime and murder rates before pivoting to MS-13.

Conflating immigration with increased levels of crime dates back at least back to Know-Nothing hostility toward the Irish. Similar accusations were leveled at Italians when immigration from that country was peaking. President Trump, in making his campaign announcement, infamously described Mexicans immigrating to this country as “rapists” and drug dealers who were “bringing crime.”

Four key elements of immigration policy changed in 2017: the deportation of non-criminals, the travel ban from certain majority Muslim countries, the phasing out of DACA, and the end of Temporary Protected Status (TPS) for Haitians and Nicaraguans. DACA allows young people whose parents brought them to the U.S. without authorization to go to school and work, legally. There are about 8,000 DACA recipients in Maryland—of an estimated 24,000 who are eligible, and nearly 800,000 recipients nationwide. TPS grants temporary status for those who fled their country because of natural disaster, public health crisis, or civil war. Salvadoran TPS recipients lost their protected status this January.

lithuanian hall in hollins market.

But blaming crime on immigration—which, in truth, has fallen sharply in the U.S. in recent years—is misguided.

Numerous studies show immigrants commit crimes at much lower rates than native-born citizens. The libertarian Cato Institute found illegal immigrants are 44 percent less likely to be incarcerated than native citizens. Legal immigrants are 69 percent less likely to be incarcerated than natives.

Other facts around immigration fly in the face of stereotypes.

Bureau of Labor statistics show foreign-born men, far from being a drag on the economy, participate in the workforce in higher percentages than their native-born counterparts. Immigrant workers also pay taxes. Foreign-born Hispanics, for example, contributed $96.9 billion in tax revenues nationwide, in 2015, according to study by the New American Economy.

Immigrants are also needed as replacement workers as aging baby boomers retire, say economists. And, in Baltimore, the growing Hispanic community, which doubled to 32,000 from 2005-2015, is also preventing the city’s sagging population and school enrollment numbers from falling through the floor. (State funding for public schools is based on enrollment.) Immigrants, in Baltimore, as elsewhere, open new businesses in higher numbers than native-born citizens as well.

“The economy and jobs are just not a zero sum game,” says John O’Keefe, an assistant professor of history at Ohio University-Chillicothe, who is working on a book about American immigration. Still, it can be hard for researchers to get their numbers into the public policy debate, especially when politicians make appeals to fears of crime and economic insecurity, O’Keefe says.

“When we have problems with crime and drugs, like today with opioids and heroin, we blame others and we tie it to de-industrialization in Ohio, in Pennsylvania, in Baltimore,” O’Keefe says. “We blame cheap labor in Mexico and China, and the cheap labor of immigrants. Then politicians and others paint looming, dangerous stereotypes that apply to Muslims and Mexicans and Central Americans. It’s very generalized and very understandable. This isn’t the romantic golden age of unions, higher wages, and lifelong jobs with health benefits any longer.”

irish railroad worker’s museum. zion church downtown.

Undocumented immigrants also do not qualify for welfare, food stamps, Medicaid, and many other public benefits. Most of these programs require proof of legal immigration status, and since the Clinton Administration's 1996 welfare reform law, even legal immigrants cannot receive these benefits until they have been in the U.S. for five years.

None of the attacks on immigrants are new, says University of Washington professor emeritus Charles Hirschman. “It’s a broken record. Substitute anti-Latino and anti-Muslim for anti-Irish, anti-Italian, anti-Catholic, and anti-Jewish. Our grandchildren of those immigrants forget all that.”

What differs today from the eras of European immigration in the mid-1850s and early 1900s is the government’s characterization of immigrants as criminals and its sweeping deportation efforts.

Simply put, prior to 1924 there were few laws regarding immigration. Passports had not even been required until 1918. New arrivals only had to prove their identity and find a relative or friend who could vouch for them.

“If you were healthy, you were in,” says Fessenden. “In Baltimore, 1 percent were detained. Visas didn’t exist until 1924.”

It is worth noting that Italians and Jews, two of the most prominent immigrant groups in Baltimore, were among the first groups restricted from entering this country and threatened with deportation. (The Chinese had been the first, in 1880.)

St. Michael the Archangel Ukrainian Catholic Church across the street from patterson park.

Then came the 1924 immigration law, known as the Johnson-Reed Act, which slashed immigration and created permanent restrictions designed to keep out Southern and Eastern Europeans, particularly Italians and Jews, but also Africans and Middle Easterners, while barring Asian immigration entirely. The law limited total immigration to 150,000 per year, cutting each nationality’s allowance to 2 percent of its U.S. population. “It was prejudice and racism,” Fessenden says. “There’s no other way to describe the intention.”

Nonetheless, Jews and Italians did not stop immigrating, becoming some of the first “illegal” immigrants to pour over the Canadian and Mexican borders. At one point in the 1920s, a Bureau of Immigration supervisor in El Paso, Texas reported “the number of European aliens arrested in this district annually increases, and the prediction is made that the situation . . . will grow worse instead of better,” according to Libby Copeland’s After They Closed the Gates: Jewish Illegal Immigration to the United States, 1921-1965.

Many of these unauthorized European immigrants—an estimated 200,000 from 1925-1965—eventually benefited from amnesties. Acknowledging the large numbers of Europeans without authorization, the government devised means for them to remain legally. The 1929 Registry Act allowed “honest law-abiding alien[s] who may be in the country under some merely technical irregularity” to register as permanent residents if they could prove they had lived in the country since 1921 and were of “good moral character.”

Today, no one believes having 11 million undocumented residents is a good idea, and both political parties describe the immigration system as broken. While many recall the amnesty signed by Ronald Reagan in 1986, few note that a decade later, Bill Clinton signed a law overhauling immigration enforcement, laying the groundwork for today’s systematic deportation.

After 1996, it became more difficult for unauthorized immigrants to become legal. Previously, those who’d been in the U.S. for seven years could gain legal status if they could demonstrate that deportation would cause extreme hardship. The changes also mandated the detention and deportation of noncitizens who had been convicted of an expanded list—for immigration purposes—of “aggravated felonies,” including individuals who may have pled guilty to minor charges to avoid jail and opt for probation.

Without the 1996 law, it is estimated there would be 5.3 million fewer unauthorized immigrants in the U.S. More stayed in the U.S. because going back and forth between their native country became more difficult.

Walter Ewing, Ph.D., a senior researcher at the American Immigration Council has a phrase for today’s immigration enforcement efforts. He calls it “the Great Expulsion.”

Alejandro Garcia’s children have never known a home other than Baltimore, but this month, with their mother, they will be leaving the United States and joining their father in Guatemala. Neighbors and friends pitched in for the family’s last few months of rent and then assisted with the purchase of plane tickets.

His sister Maria translates the conversation with her brother in Guatemala by phone from the family’s kitchen, out of earshot of the children: “Everything he was working for, that he wanted for them, has been lost now, my brother says. All his dreams for them, going to college, everything.”

He says he makes about $2 to $3 a day, if he’s lucky enough to find construction work. The choices, his sister explains, are between food, shoes, school supplies, and health care for the children there. Garcia’s son has a heart condition that requires daily medication.

Everybody has different attitudes about immigration, Maria acknowledges later, sitting on her brother’s living room sofa beneath family photos.

After a long pause, she smiles. “I love Baltimore. I love this country." if deported, she says she will go with no animosity.

“I don’t blame people for feeling the way they do,” she says. “Even the people I work with. Some people understand why my brother came to this country and what he was trying to do for his family, but other people don’t understand why he came.

“To people who don’t understand, I think they must not understand what it is like to have no food, no chance for an education, to live in extreme poverty—to try to live like a human being in those conditions. President Trump and some other people think we are criminals, but that’s wrong.”

She is also scared for her kids. “They don’t know any other country. I am fearful about what is going to happen this year.”

After a long pause, she smiles. “I love Baltimore,” she says. “I love this country.” She feels close to her friends and neighbors. If she is deported, she says that she will go with no animosity.

“I have met so many great people here. My life has already been changed forever for the better,” she says. “My neighbors, Latino and American, are good people. We look out for each other; we take care of each other.

“Highlandtown is my home,” she says. “I have found a good place to live.”