History & Politics

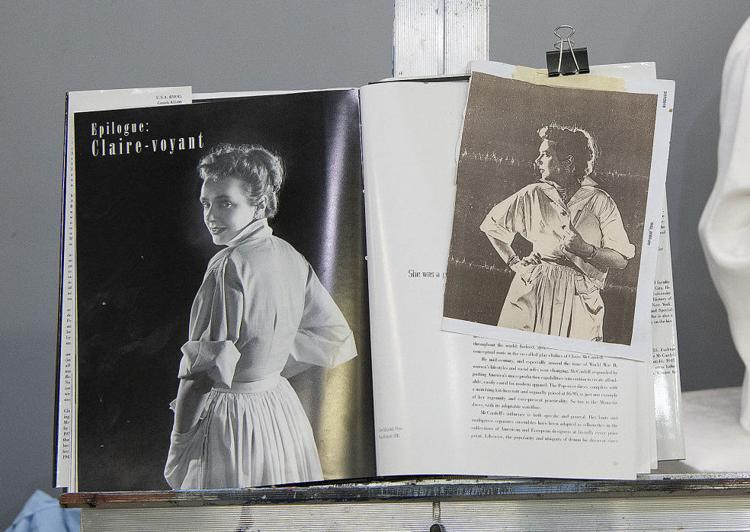

Claire McCardell Statue Will Honor Groundbreaking Frederick-Born Designer

Currently, less than 7 percent of U.S. monuments recognize women.

“You know why women love Claire McCardell?” says sculptor Sarah Hempel Irani. “Because she gave us pockets. And then she gave us flats.”

The only girl of Eleanor and Adrian McCardell’s four children, Claire McCardell was born into a well-to-do family in Frederick in 1905. She climbed trees, rode horses, skied, and acquired the nickname “Kick” for her skill in keeping roughhousing boys at bay. She also made outfits for her paper dolls from her mother’s magazine photos, kept an interested eye on local seamstress Annie Koogle when she sewed clothes for the family, and liked to tear apart her brothers’ less-restrictive clothes to see how they were pieced together.

The visionary behind ready-to-wear fashion for women on the move, she’d later create sporty cycling ensembles for women and incorporate menswear details in her signature designs.

“She wouldn’t have called herself a revolutionary,” Hempel Irani continues, “but what she did was revolutionary.”

McCardell tossed aside girdles, darts, shoulder pads, and unwieldy zippers that ran along the back of garments, as well as Paris fashion trends, and developed the distinctive, mid-century style known as The American Look that embodied both elegant simplicity and practical purpose.

“I like buttons that button and bows that tie,” she once said. More recently, McCardell’s designs served as the go-to fashion inspiration for the Emmy-winning Amazon Prime hit The Marvelous Mrs. Maisel.

As always, necessity was the mother of her inventions. When leather and rubber were in short supply during World War II, she turned to shoe manufacturer Capezio to help repurpose ballet slippers into functional footwear that fit her designs. To lighten her luggage on her European travels, McCardell created separates by designing dresses with interchangeable blouses and skirts.

Over a groundbreaking career as a designer and businesswoman, she became one of the 100 most important Americans of the 20th century, according to Life magazine, influencing designers from Diane von Furstenberg to Michael Kors and Donna Karan.

“She modernized the way women dress,” designer Anna Sui told The Washington Post. “Her clothes are timeless.”

Two years ago, the all-women’s Frederick Art Club, founded in 1897, decided the time was long overdue to honor McCardell, whose clothes are part of the collections at The Metropolitan Museum of Art, the Smithsonian, and the Maryland Center for History and Culture.

Initial plans called for a relatively modest bas-relief sculpture. But as they delved into their subject, they realized they wanted to make a larger statement that would reflect the enormous impact of her democratizing designs for the women of her era, who were seeking freedom and new roles in the workplace and society.

“Newswomen, in particular, were crazy about her,” says Linda Moran, chair of the Art Club’s Claire McCardell Project. “They gave her two Coty Awards.”

Eventually, they commissioned Hempel Irani, an award-winning sculptor who had recently moved back to Frederick, to create a 7-foot-6-inch bronze sculpture to pay homage to the designer in her hometown. (McCardell, whose life and career were cut short by cancer in 1958, is buried in the family plot at Frederick’s Mount Olivet Cemetery.) The bronze statue, with accompanying signage that will share her story, is scheduled for a fall unveiling at the city’s Carroll Creek Linear Park, Fredrick’s popular downtown greenway.

With the endeavor, the Art Club joins a national “break the bronze ceiling” movement to lift more monumental women on pedestals. Currently, less than 7 percent of the more than 5,100 monuments in the U.S. honor women.

As a teenager, Claire McCardell had hoped to study in New York. But, in a sign of the times, her father initially persuaded her to enroll at nearby Hood College in the home economics program. After two years, the somewhat shy, yet unwavering, McCardell moved to the Big Apple and enrolled at the Parsons School of Design.

Single and working for a designer in Manhattan, her big break came at 33 when a buyer for a major retailer noticed the dress McCardell was wearing. It was not a part of the company’s line he’d been shown, but something she had designed. What became known as “the Monastic Dress” hung loosely, but with a versatile belt that could be gracefully tied to follow a woman’s curves. The initial order sold out in a day.

“I’ve always designed things I needed myself,” McCardell later said. “It just turns out that other people need them, too.”