History & Politics

Victor Blackwell Settles In as Co-Anchor of CNN’s Weekday ‘Newsroom’

Former Milford Mill Academy class president discusses his career, the state of broadcast journalism, and how his deep Baltimore roots inform his work.

In July 2019, President Donald Trump attacked Rep. Elijah Cummings in a Saturday morning tweet, referring to his district, our city, as a “disgusting, rat and rodent infested mess.” As Baltimoreans recoiled and fumed, weekend CNN co-anchor Victor Blackwell memorably called out Trump’s racism on air, in real time—noting the president had only used the word “infested” in previous efforts to degrade congresswomen, immigrants, and districts of color, as well as parts of Africa.

“The President says about Congressman Cummings’ district that no human would want to live there,” Blackwell told viewers before addressing Trump directly. “You know who did, Mr. President? I did, from the day I was brought home from the hospital to the day I left for college, and a lot of people I care about still do.” Blackwell continued, in just a handful of sentences, to point out the many hardworking people and families in the 7th District, and the community’s patriotism, while also acknowledging its challenges. “They are Americans, too.”

The former Milford Mill Academy class president and Howard University graduate got emotional at the end of his rebuke and his poignant commentary garnered national attention. But on a daily basis it’s been Blackwell’s poise, preparedness, and interview skills—like when a Texas legislator suggested he should read his education bill and he lifted up his own highlighted copy of the proposed law—that set him apart behind the desk.

With CNN since 2012, Blackwell earned a well-deserved promotion last April from weekend co-host to afternoon co-anchor of CNN Newsroom. Not that it’s been an easy path. He’s paid his dues, starting as an overnight assistant at WBAL Radio while in high school, and then as a reporter and anchor in Hagerstown and Jacksonville, Florida. He later became the first Black lead television anchor at WPBF in West Palm Beach before CNN scooped him up.

We caught up with Blackwell to ask him about his career, the state of broadcast journalism, and how his deep Baltimore roots inform his work.

Can you recount the scene on set after Trump’s tweet attacking Rep. Cummings and Baltimore hit Twitter?

We had a nine o’clock break and then we were back on at 10 a.m. I saw the tweet and I knew Rep. Cummings well because I was a participant in his youth program in Israel. When I saw it, the word “infested” jumped off the screen at me. I remember the president having used it in reference to The Squad [Reps. Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez, Ilhan Omar, Ayanna Pressley, and Rashida Tlaib] a couple of weeks prior. I did a simple search and saw how many times he has used the word “infested” and found it in reference to Ebola and to sanctuary cities in California, and that was it—in the entire eight-to-nine years of the account.

I told my producer I was going to write something in the break and I wanted to highlight when the president uses this. Then I thought, “Should I take the next step and talk about the district and idea that no human being would want to live there?” I went back and forth. But I decided there was really no one else in my position, on a national network at that point, who could speak from the 7th District, so I decided to. The emotion was a surprise to me because I do my best not to let my emotions carry me away. So I held back, which is why I was as silent on air for as long as I was. Trying not to continue with a cracked voice. But I wrote that myself, in probably about 10-to-15 minutes.

And your first broadcast gig was the morning announcements at Milford Mill?

Well, I did the morning announcements at Woodlawn Middle School, too. But yeah, I found a little theme song on a cassette that I’d play into the microphone before I started the announcements.

Why Howard University?

My mom always gave me three options as a kid: “You can take a job and take care of yourself. You can join the Army and Uncle Sam can take care of you. Or you can go to college and I’ll take care of you.” I chose college. She tried to talk me into Howard because she knew of the alumni. When I started choosing, she said, “You can go to any school you want. I’ll pay for any HBCU you choose.”

Your mother sounds like the kind of mom who never missed a school play.

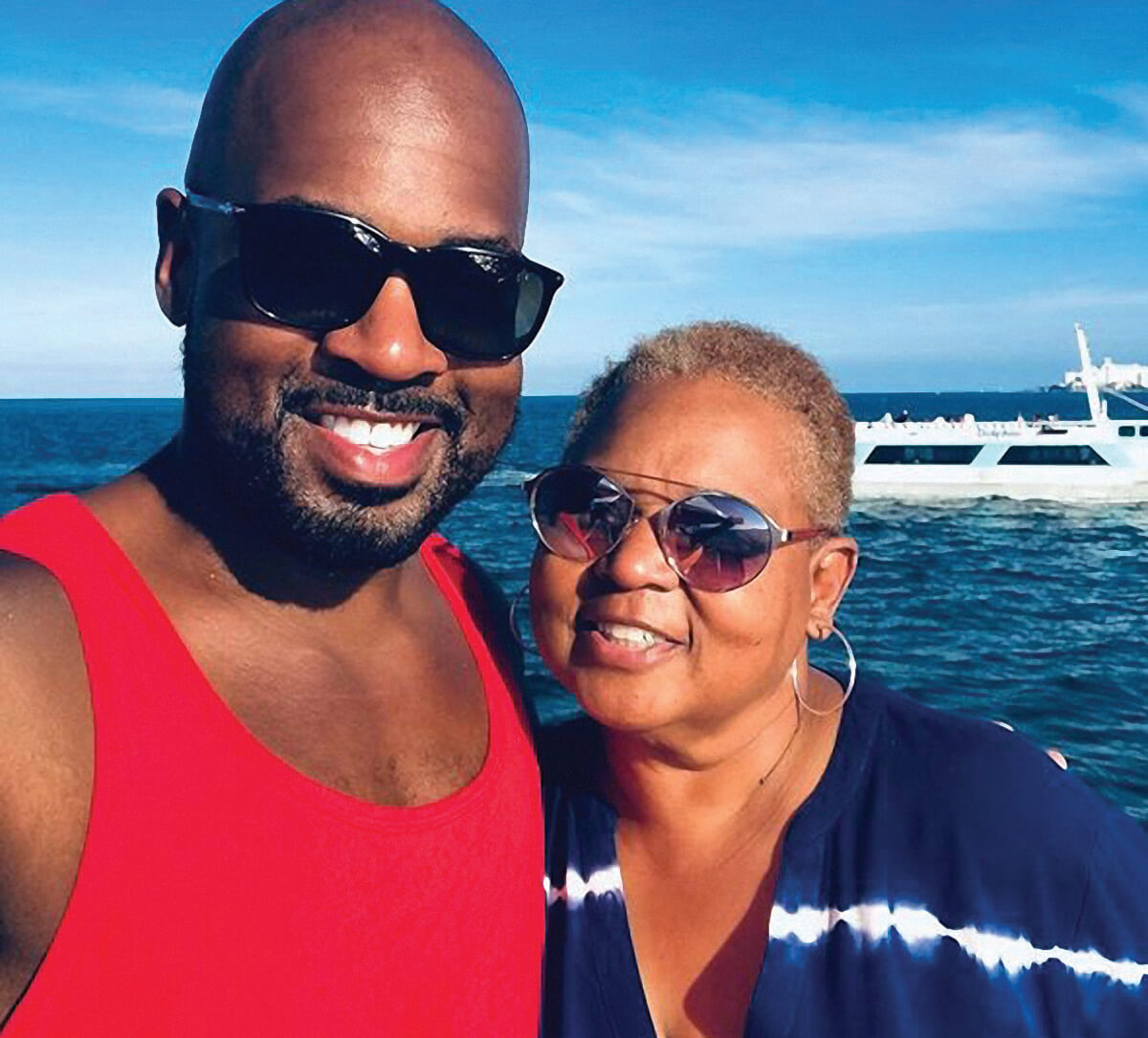

My mom literally texts me after every show.

Why journalism?

I was in 4th grade in Mrs. Mulcahy’s class, whom I haven’t called recently, but I still keep in communication with. She told us the story of Paul Revere and the Midnight Ride and I thought it was cool—this guy on the horse—and couldn’t wait to get home and tell my mom this story. And she was like okay, “I get it, you tell people and they can protect themselves,” bringing the story to my level. I thought, that’s what I wanted to do. Paul Revere wasn’t a job right?

I’m nine years old and I’m trying to figure it out. The person I equated to that role was [WJZ anchor] Al Sanders. Al Sanders, to me, at that point, was the guy I wanted to be. Al Sanders was never loud, he was never boisterous, smooth as butter, and a Baltimore institution. Eventually, I decided that was the job I wanted.

How do you drill down to what is most critical in the limited time you have on air?

If I’ve asked the question and someone has spoken for 45 seconds and that was not an answer to my question—I’m going to double up. If this is the reason we invited you here, I’m going to try a third time, and sometimes no answer is an answer. I get that and the viewer gets that.

You’ve been at CNN for nine years and the news cycle only gets faster. Then, there are unprecedented “fake news” attacks.

When I started in 2012 on the weekend show, we made smoothies, I did push-ups, crunches—we had a health segment. It was a different time, a different show. Certainly, the 2016 election shifted the show. You’ll remember there was a stretch where a member of the administration lost a job every Friday night. I [started] going to sleep at 5 p.m. on Friday and then getting up at 11:30 p.m. to start preparing for the weekend show because [inevitably] there was a tweet and a firing.

I remember the day the former president tweeted out a GIF of him body-slamming someone with a CNN logo as their head. My car was keyed that day, from the CNN sticker where I had my parking decal all the way down the side.

“I feel like I bring the versatility of the city with me.”

You and Newsroom co-anchor Alisyn Camerota, a white suburban mom from New Jersey with three kids, seem to complement each other.

Being Black and gay from West Baltimore is different [than her background]. I think it is important to have people from different backgrounds and different life experiences. People use the word chemistry, but the work is being generous, it’s listening, it’s being open to ideas and perspectives. That for me is what people see as chemistry. It’s easy with Alisyn. I trust her and the people that I work with are coming to this purely in good faith, and we can engage on questions about race and LGBTQ issues. I have no problems with that.

How do you handle someone spreading misinformation or disinformation on air?

We have to confront misinformation and disinformation every time. [CNN anchor] Brianna Keilar said one time, “You can’t just leave bullshit, you have to shovel it.” That will stay with me. But I don’t think we should be bringing people on who are spreading disinformation and misinformation just for the purpose of challenging that. The goal should be more light than heat. Sometimes there is heat, but the goal should be light.

What does coming from Baltimore bring to your work?

Baltimore is unique and has its own culture. There’s the history—from Frederick Douglass to Francis Scott Key. Its texture is both beautiful and blighted in some areas. That has helped me in my role. There’s the Inner Harbor and U.S.S Constellation, and the stretch of North Avenue with block after block of vacant houses, and there’s Druid Hill Park, the history of Lexington Market—my family has been going to Faidley’s for generations. I feel like I bring the versatility of the city with me.

This past fall, you did a compelling special with the teacher and the class that former President George W. Bush was reading to when 9/11 happened. Is there another story you’d like to do?

Certainly, I’m pitching some. But one person I’d like to profile is Marian Robinson, the former president’s mother- in-law. From raising Michelle Obama on the South Side of Chicago to reaching the White House [she moved in as the First Grandma], the arc of that story is notable. I think that would be a good one to tell.

What is it like to be in the front row to history? Find out when Victor Blackwell talks with the students who, 20 years ago, were with President Bush on 9/11. This CNN Special Report airs Sunday at 10 p.m. ET pic.twitter.com/Wd4VgIK3Mo — CNN (@CNN) September 2, 2021

Is there an interview that stands out?

I’m not into celebrities. One that sticks with me was the story about a senior home in Hagerstown run by a charity that was losing state funding. With a month to go, these people were going to a shelter because they had no next of kin. I did the story and funding was restored. This was me carrying my own camera, a one-man band; this wasn’t CNN. At the end of this career, I don’t know that I will remember one interview with a member of Congress. [I will remember] this man in his eighties crying, not knowing where he was going.

And you came back to report from Baltimore after the death of Freddie Gray.

I was traveling in Port-au-Prince, Haiti, and I remember seeing teenagers [on CNN at the Marriot hotel there] running out of Mondawmin Mall. That’s where I bought my junior prom shoes—I know North Avenue. I wanted to show the frustration was not only over the death of Freddie Gray. It is, in large part, from broken promises over generations for some families. And that what viewers saw, the vacants on North Avenue—that’s not the result of the riot the night before—these homes have been in this condition since I was a boy. It’s because of a lack of investment and support.

You also sat down with three Baltimore high-school boys at that time.

We had to get them home before curfew, but they went to the high school Freddie Gray went to, and they told me about feeling trapped, that they don’t have a way out. When that story aired, the president of Bethune-Cookman called and said he wanted to offer those three boys a scholarship, a full-ride. And we did a follow-up, recorded them flying down and moving in [the dorms]. But one left during the first year and other two left the next year. I really feel I should’ve or could’ve done more. I flew down several times to visit. I met with the president and an advisor, and told them if they needed anything to contact me—“If you need a tutor, I will make a call.”

They just weren’t prepared. They did not have a lot of support in high school, and we’re not in contact anymore. I got the little plaque from The Baltimore Sun when they did a story [about the students starting at Bethune-Cookman], but I can’t bring myself to hang it up. That’s another one that stays with me.

Ultimately, what’s your reward from journalism and sitting in the anchor chair?

A reporting job is going out, talking to people, and listening to people, and finding out things. I’m naturally inquisitive. Sometimes I travel by myself, and intentionally get lost and find things I can do and read. The anchoring part is I’m someone who talks to the TV and asks questions even when I’m not doing this job. So the fact is, I can now ask a member of Congress, “Well, what was the point of that?” instead of just doing that in my living room. That may not be the answer the network wants me to give. [But] that’s the payoff for me.