History & Politics

Deer Park, MD Was Once an Elite Vacationland—Thanks in Part to its Famous Water

Now little more than a sleepy whistle-stop, it’s part of an unlikely tale intertwined with the Baltimore railroad, the Appalachian Mountains, and Maryland history.

If you’re looking for Deer Park, Maryland, just follow the railroad—out of the city, over the rolling countryside, through the foothills, and up into the Appalachian Mountains, as if heading for the clouds.

Out here, a serpentine path of iron track weaves its way west, following the Potomac River and existing as an ever-present shadow as you travel along the panhandle of the Old Line State. And over the Continental Divide, en route to Oakland, then onwards toward Ohio, it eventually passes through this whistlestop, just a stone’s throw from West Virginia and a shorter drive to Pittsburgh than Baltimore, now some three hours in your dust.

Upon arriving, it’s hard to imagine that Deer Park was once a major destination—drawing presidents, celebrities, and other well-heeled city-dwellers to a vacationland first named “Peace and Plenty” for its natural abundance, boundless scenery, and fresh mountain air. Through the snowfalls and mists of its 2,448-foot altitude, this tiny town—population 306—is now little more than a scattering of houses, trailers, old tractors, yard chickens, a church, a playground, and a long-closed general store.

In fact, there’s barely a trace of its former glory days, other than those train tracks and, beside them, a baby-blue, gated-off building, emblazoned with an antlered deer skull and white letters that read SPRING WATER.

“Sometimes you wish you could flip a switch and go back in time,” says the town’s mayor, Donald Dawson, 50, who has lived here most of his life. “I find myself doing that quite a bit—trying to picture what it used to look like. I’d love to see it boom again, like it did way back when.”

IF YOU LIVE IN THE MID-ATLANTIC, enter any grocery store or gas station today, and you’re likely to find a cooler filled with bottles of Deer Park Natural Spring Water. This prolific brand is a household name, and while its parent company is now headquartered in Connecticut, it has humble beginnings in Maryland, born just south of the railroad tracks in its namesake hamlet in 1873—making Deer Park, alongside the likes of Poland Spring and Mountain Valley, one of the oldest water companies in the United States.

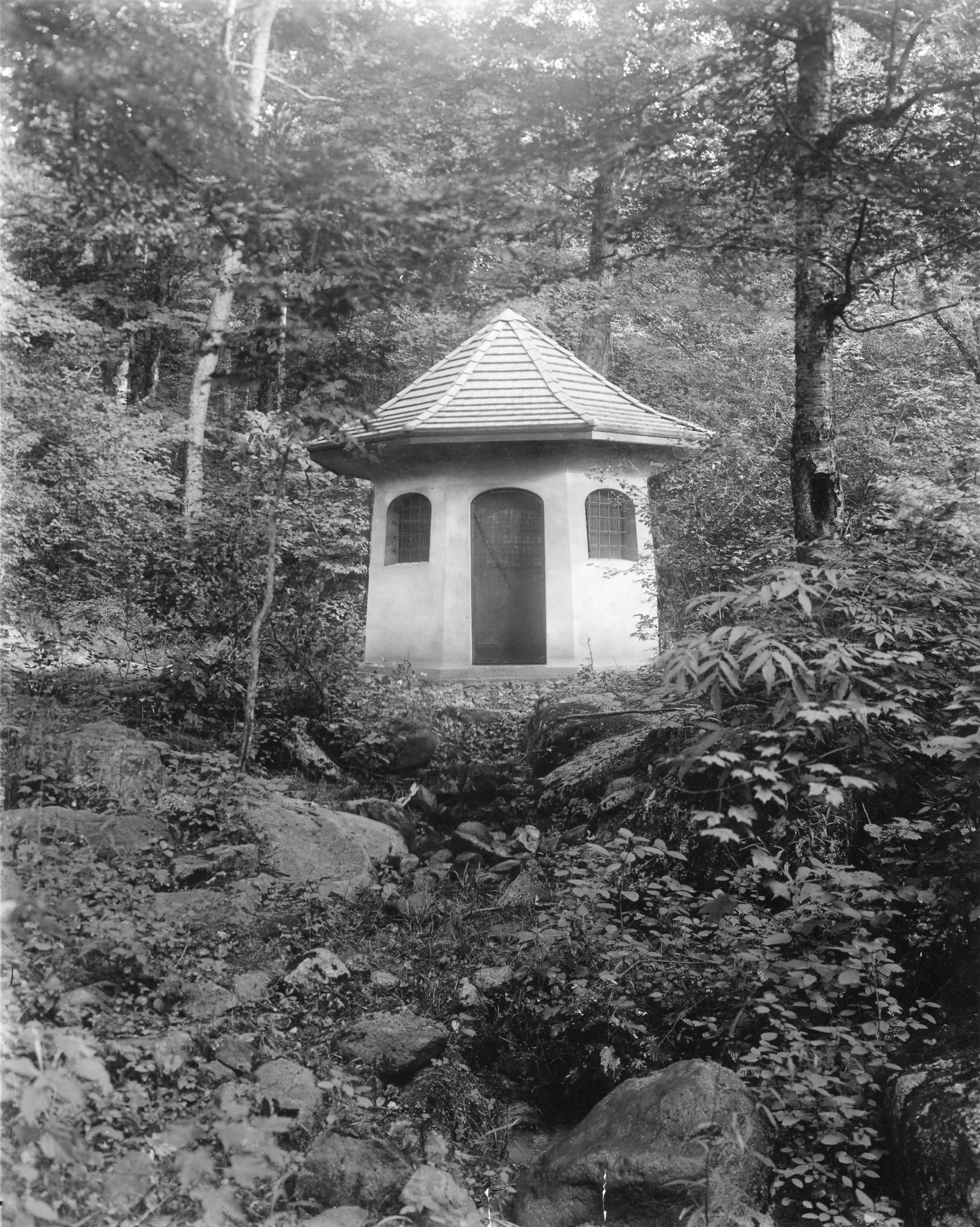

And down a winding backroad, tucked into the forest amidst the ferns and rhododendrons of this alpine terrain, Deer Park’s Boiling Spring is still flowing strong, 150 years later, fed by a sprawling underground aquifer made of limestone and sandstone, spanning some 40 miles beneath Pennsylvania, Maryland, and West Virginia. Precipitation falls and becomes groundwater, which fills the aquifer, eventually flowing up to the Earth’s surface, where it escapes via a range of regional springs, such as this one.

“Most of that water ends up flowing downstream,” says Eric Andreus, natural resource manager for the Deer Park Natural Spring Water brand. “Block Run eventually enters the Little Youghiogheny River, and then it begins its journey, ultimately ending up in the Ohio, which feeds into the Mississippi.”

The story goes that this particular source was named for the way that its waters bubbled up through the sand of surrounding creek beds, giving the appearance that it was, in fact, boiling. Then and now, it gushes forth at a rate of approximately 100 gallons per minute, or 150,000 per day.

“The water has always been a huge life source for this area, along the Laurel Highlands of the Allegheny Mountains of Appalachia,” says Karen White, curator at the Garrett County Historical Society Museum in nearby Oakland. “Indigenous people followed the rivers, and that led to some of our first trails”—then roads, then rails, too.

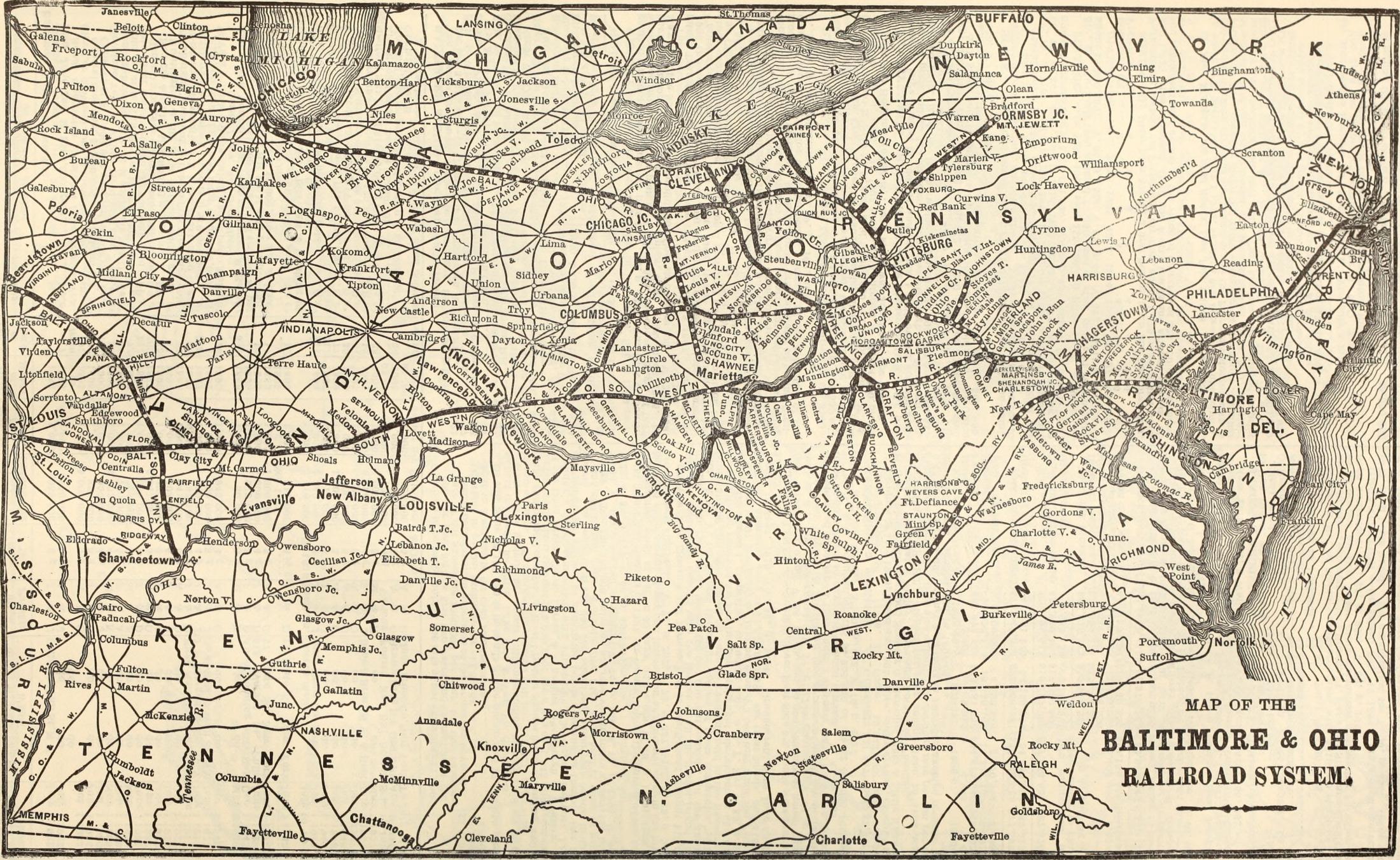

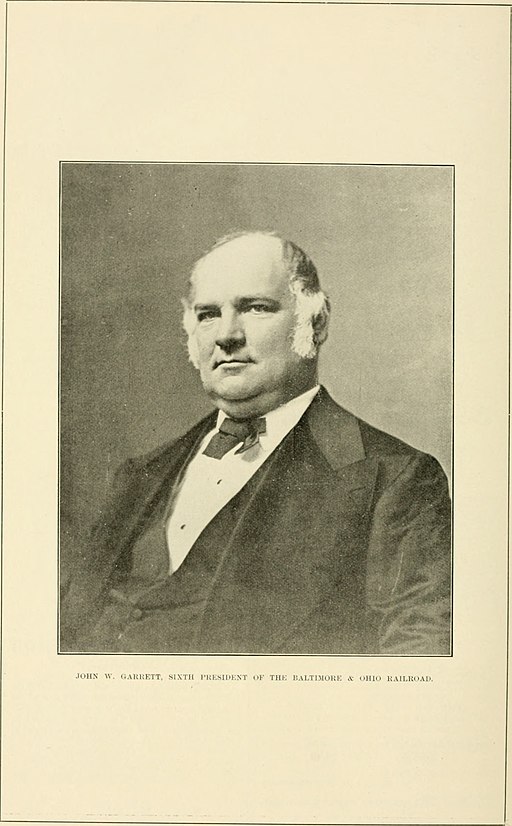

Indeed, it was this natural bounty that first caught the attention of John Work Garrett, a Baltimore native and prosperous businessman turned president of the Baltimore & Ohio Railroad, headquartered 200 miles east of Deer Park on West Pratt Street in the Pigtown neighborhood of Baltimore City.

Before the Civil War, the company’s tracks were unfurled westward, eventually passing right through what would one day become Garrett’s namesake county—at the time little more than coal, logging, and lumber country, known among Marylanders as “the outpost.”

The son of an Irish immigrant, Garrett’s father, Robert, “was a dry goods salesman in Baltimore who sold his merchandise up and down the National Road in Conestoga wagons to people on Westward Expansion, so he became very familiar with this neck of the woods,” says White, noting that John eventually joined the family business. “And as their prosperity increased, they also became aware of investing in land. . . . This area had started to become a summer resort for the very upper class of Baltimore—the McHenrys, the Howards, the Keys—and John Garrett capitalized on that. He understood its potential.”

“The water has always been a huge life source for this area.”

“The salubrious climate and beautiful country among the highlands of Western Maryland have elicited much attention during the past season,” Garrett wrote in his B&O Railroad report in 1857. “But the absence of adequate hotel accommodations has materially checked the tendency to seek these Glades for summer homes. Arrangements are being made for additional hotels; and a large population, from the South, West, and East will probably hereafter select this singularly picturesque and attractive region for summer resort.”

The Civil War would stall his grand vision, but in 1865, the B&O approved its first train station in the then-unincorporated town of Deer Park and, three years later, purchased more than 300 acres of land beside it.

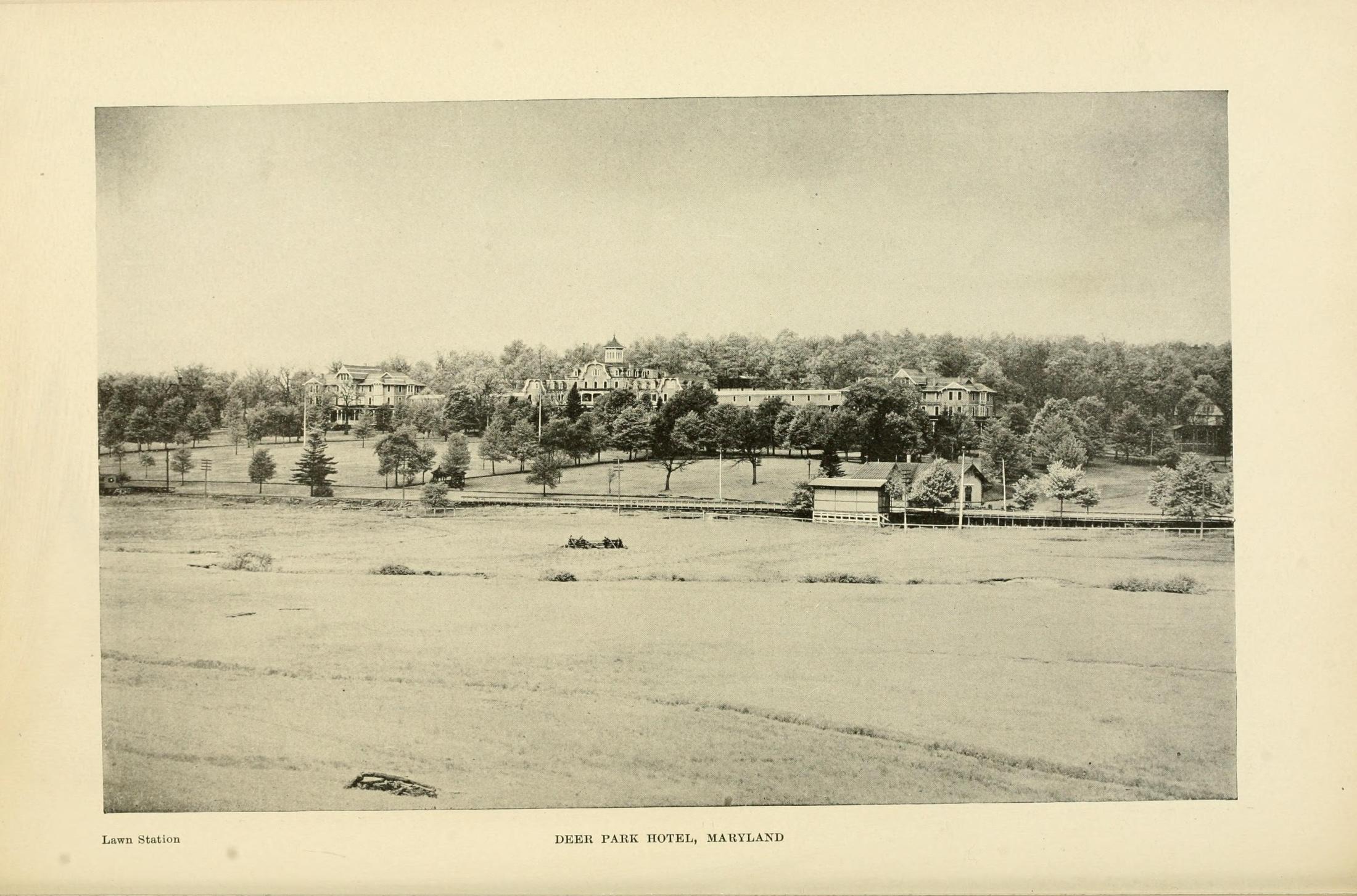

On the Fourth of July, 1872, construction began on the Deer Park Hotel—a four-story, Swiss-inspired luxury inn, billed as “the most delightful summer resort of the Alleghenies” in an era of no air-conditioning and, enticingly, “absolutely free from malaria, hay fever, and mosquitos.”

These were the early days of modern medicine, with crowded cities being fertile breeding grounds for infectious diseases like smallpox and tuberculosis, spread through the air like COVID-19, as well as dysentery, cholera, and typhoid fever, via contaminated water sources.

Not only was spring water hailed as free of urban contagions, but thanks to its purported purity and natural mineral content, for its healing and health benefits, too. (In fact, Poland Spring, circa 1845, was originally marketed around Maine as a kidney remedy.)

“People were starting to understand that the cities were filled with pestilence—you took your sewage and dumped it out in the street, it went into the Baltimore Harbor, then you drank the water, and it killed you—so they flocked to the mountain air and water,” says White. “You see it with the old breweries, too; think of Coors, which came from the Rockies, which made it better. And I’m from Cumberland, where the beer boasted that ‘mountain water makes the difference.’”

It was certainly a boon for the B&O Railroad, which started serving local water from Boiling Spring at its thriving Deer Park Hotel. Beneath the glow of new electric lights and amidst the ring of the town’s first telephones, the lavish lodgings featured 200 rooms, 10 cottages, bowling, billiards, tennis, trap shooting, horseback riding, orchestra concerts, twice-weekly dances, European-style dining rooms, and Russian baths and swimming pools, both filled with that same magical elixir, piped in from just down the street.

“The neighborhood abounds with the charms of the wilderness,” wrote The New York Times of Deer Park in 1896, “while the fine hotel buildings hold all the resources of civilization.”

Out front, the who’s who of Baltimore and Washington arrived by express train in the latest fashions. The hotel’s broad porches, lush gardens, and croquet matches brimmed with a bevy of dignitaries—theater, opera, and movie stars; famous writers, artists, and athletes; industry leaders, businessmen, and a host of politicians, from Baltimore Mayor Ferdinand Latrobe to Presidents Harrison, Garfield, Grant, Taft, and Cleveland, who honeymooned here after his White House wedding—all earning the town its reputation as the nation’s “summer capital.”

“This was the place to be,” says White, noting that Garrett’s role in providing railroads to the Union Army during the Civil War garnered him friends of every ilk. “People came from all over—Baltimore and Washington, but also Cincinnati, St. Louis, Richmond, Philadelphia, New York. . . .”

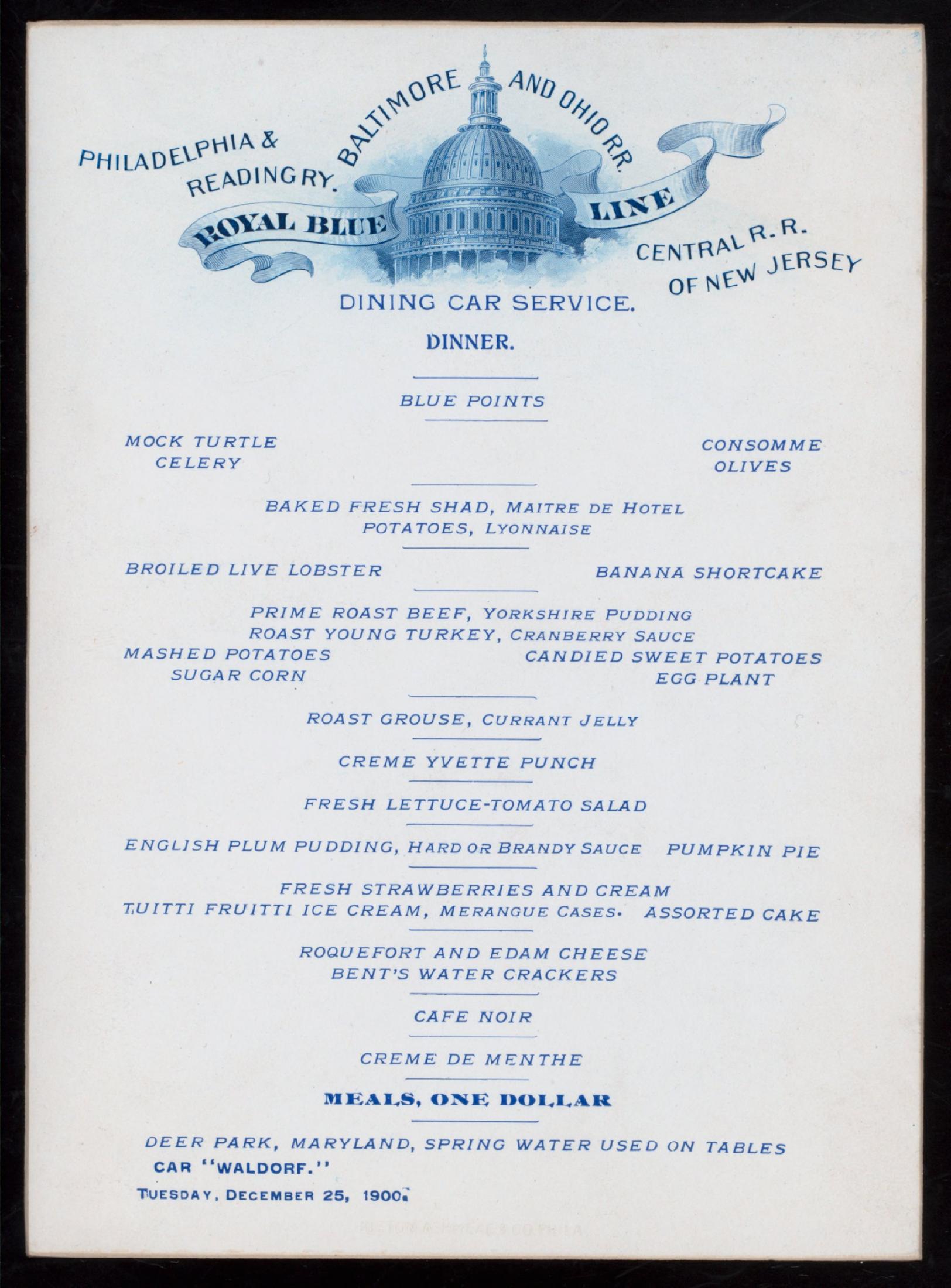

And it was those guests, by 1905, who had convinced the railroad to start serving its famous water in its white-tableclothed dining cars.

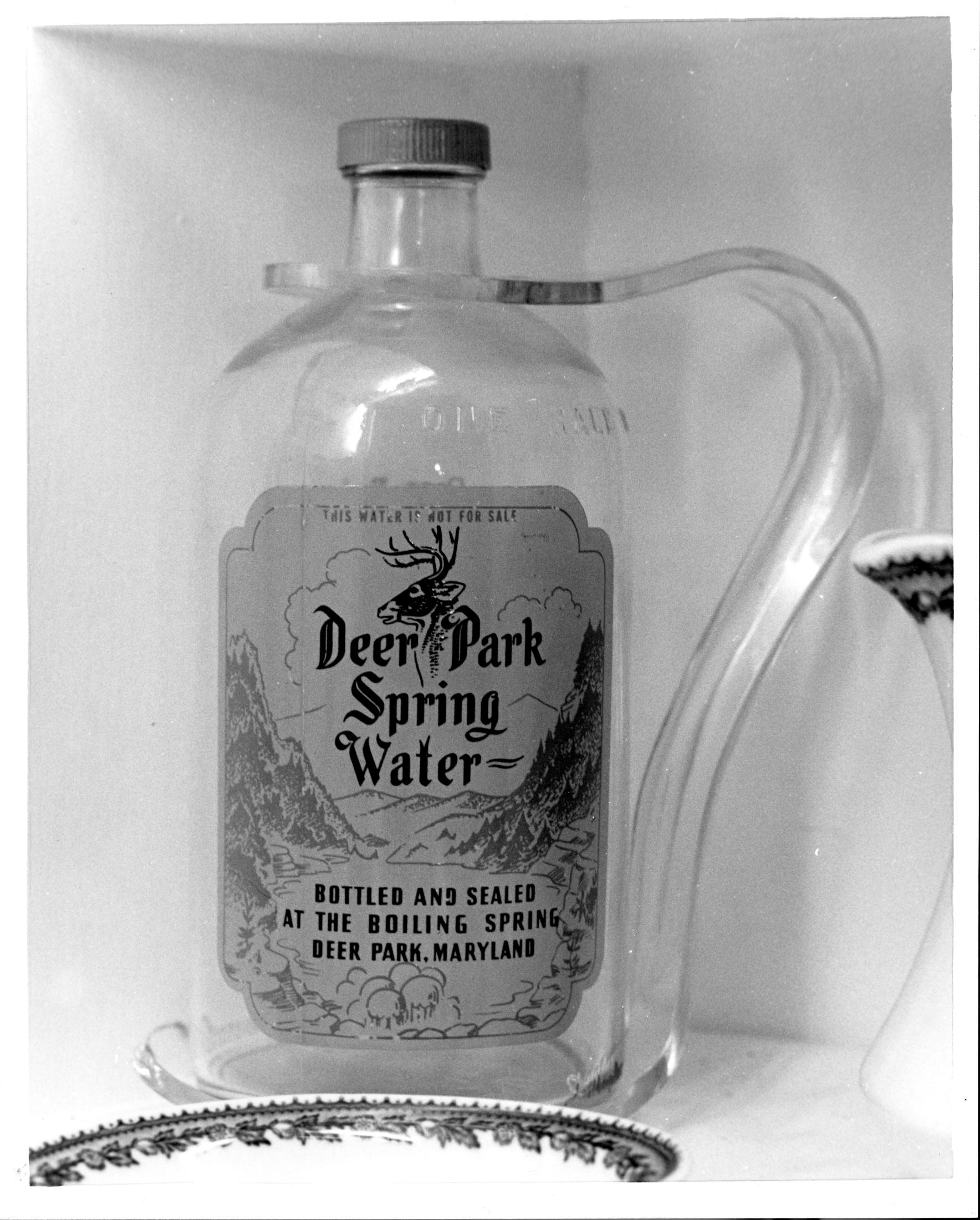

Piped straight from the source at Boiling Spring, it was first bottled in large glass vessels before being fine-tuned into half-gallons, fit with silver caps and Lucite handles, with that signature buck illustrated on the label. Those were packed into wooden cases, then loaded on the Number 222 and 30 trains for distribution. At its final destination, the water was served for free, alongside the likes of caviar and oysters.

“This was a time period when the B&O was competing with other railroads and promoting a luxury travel experience, from having their own telegraph network to the water that they served,” says Jonathan Goldman, curator at the B&O Railroad Museum, located in the original Mt. Clare Station in Pigtown. “Back then, railroad companies were doing everything—building trains, constructing bridges, cooking food—all in these giant factory towns with these giant internal supply chains. Our campus here was 100 acres.”

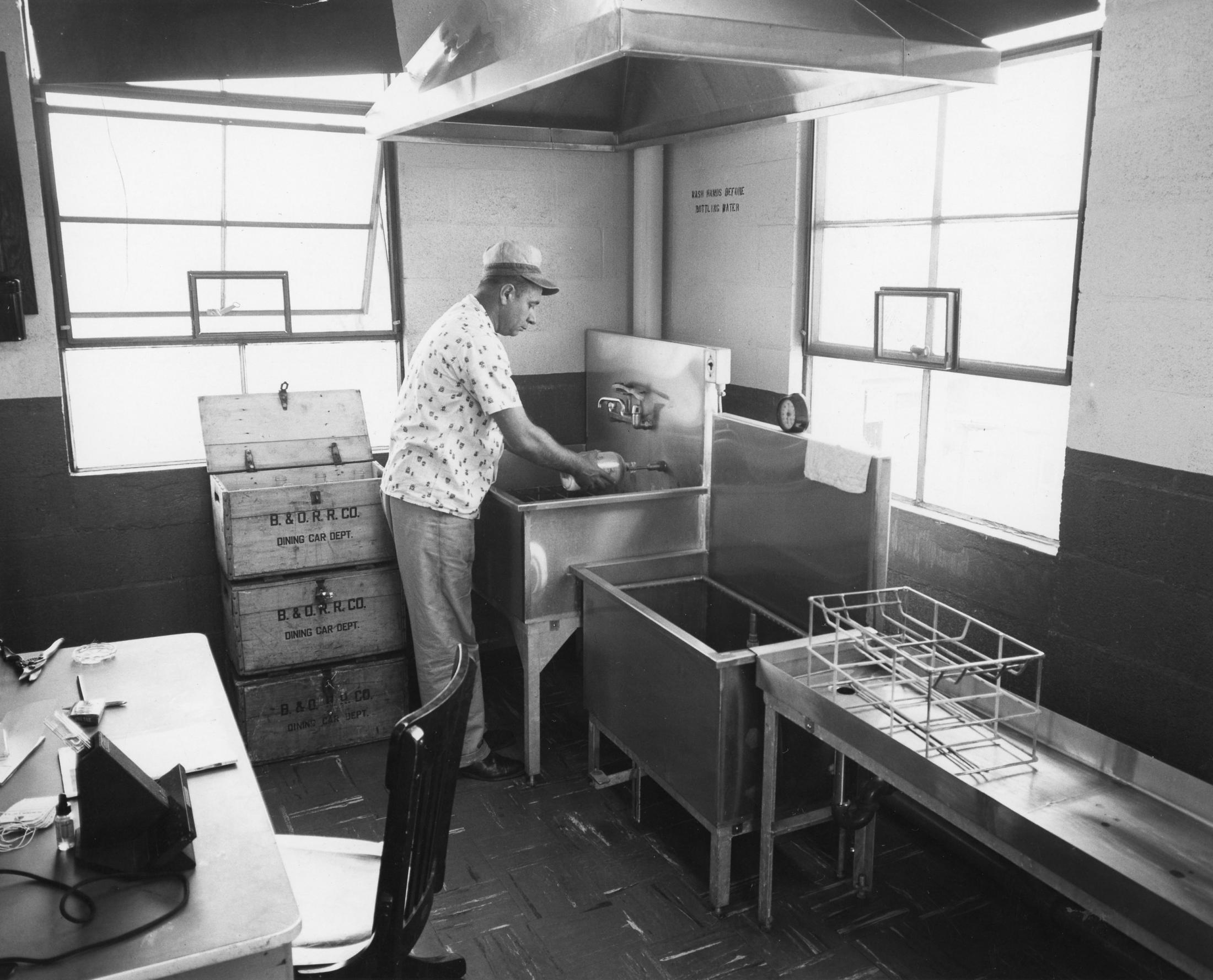

Meanwhile, back in Deer Park, a small bottling plant emerged to meet increased demand. When the glass bottles were returned by railcar, they were sterilized and refilled by a two-man operation, which included a biochemist and a supervisor from the B&O Dining Department, at a rate of 40 cases a day by the 1950s.

Eventually, they moved into a larger facility, where they ran multiple shifts and employed dozens of workers, and which is still visible from the train tracks today. Townspeople say that there was a time, not that long ago, when its overflow spigot was a de facto communal faucet.

Deer Park’s spring water continued to ride the rails until 1964. By that time, though, the resort town’s metaphorical well had already begun to run dry.

As automobiles took off in the 20th century, train travel declined, and the B&O sold its hotel in 1924. The stock market crash of ’29 would be the final blow, with the property eventually left “vacant, with boards over its windows . . . an abandoned wreck,” per a 1941 Sun article, before being razed the following year, its old oak groves cut and sawn into war-effort lumber.

These days, there’s nothing left, except for two of the guest cottages and a lone historical marker standing testament to the past. In fact, it’s nearly impossible to place the exact location where the hotel once stood, with a residential neighborhood and thickets of evergreens now covering its former grounds.

“It was peaceful growing up here—there was a lot of history, about the hotel and the trains and the water, that everybody who lived here grew up knowing about, or learning,” says Tom Upole, 46, a third-generation resident and owner of Deer Park Automotive on Edgewood Drive. “There used to be a number of train stops right through here, but when passenger service ended, everything along the way slowly deteriorated.”

That last passenger train pulled out of Oakland in 1983, with the old B&O lines now used for freight carriers, usually hauling fracking gas, coal, or timber, and many jobs heading “back down the mountain,” says White.

“It was peaceful growing up here…there was a lot of history.”

But all the while, the water remained. In 1970, Nestlé bought Boiling Spring and employed 10 workers to bottle some 3,000 gallons of water per day, sold to the masses in both glass and plastic, far and wide, from New York to South America.

“The Deer Park spring, like Old Faithful, operates at the height of dependability,” wrote a company newsletter that year. “Droughts, freezing weather, or any other tricks of nature have never caused the spring to vary its daily output.”

Meanwhile, bottled water was about to boom again, with the splashy U.S. rollout of European brands Perrier and Evian employing some of the very same tactics used over the last century by the likes of Deer Park, whose own 1971 advertising still heralded a product full of “natural minerals,” “filtered by nature itself as it bubbles from deep inside the earth,” and “untouched by human hands.”

This was no mere ploy, of course; those minerals are actually “where the water gets it taste,” explains the company’s Andreus, with every spring having its own nuance.

But as before, the public drank the Kool-Aid, and in the ensuing decades, bottled water consumption took off, growing 284 percent to nearly 42 gallons per American each year from 1994 to 2017, according to the Beverage Marketing Corporation. By 2021, it set a new total volume record of 15.7 billion gallons, or 47 per person annually, mostly out of single-servings.

But even with such demand, the industry has also felt its share of market shifts in recent years, with internet images of polluted oceans and littered fields and forests bringing societal sway toward sustainability. New initiatives among water companies include more environmentally friendly packaging, like cardboard and aluminum, while Deer Park has incorporated bottles made from recycled plastic into its lineup.

Still, in 2021, under mounting pressure, Nestlé sold its American water portfolio, which has since been renamed BlueTriton, aka the parent company of Deer Park. By then, they had already shut down the Boiling Spring bottling plant, some two decades prior, and in doing so, closed the town’s last major employer.

“I’d love to see some of those jobs come back,” says Mayor Dawson, who worked at the plant briefly, “but I don’t know if that will ever happen.”

Though some of the brand’s water still hails from its birthplace, the majority now arrives from other springs in Pennsylvania, Florida, and the Carolinas. The company employs just one Deer Park resident for day-to-day operations in Maryland.

TEN MILES UP THE ROAD, though, another local attraction has filled the void of Deer Park.

One hundred years ago, just as the railroad resort was declining, the 13-mile, man-made, but spring-fed Deep Creek Lake was built in 1923. It didn’t take long for word to spread about this year-round getaway, drawing fishermen and families in the summer and hunters and skiers in the off-season, all once again tapping into the region’s rich natural resources. And in the 1990s, when Interstate 68 shortened the drive from the east, Deep Creek became one of the state’s top tourism destinations. Located just south of Wisp Resort and east of Swallow Falls State Park, it helps draw 1.4 million visitors to the region each year.

“I try to avoid it at all costs,” chuckles Deer Park Automotive’s Upole, echoing a common sentiment shared by many Garrett Countians. “Before the interstate, locals used the area for recreation, but today, it’s built up and overrun with tourists. I’m getting ready to go to Disney World and I think it’s almost cheaper to spend a week there than it is to stay at the lake.”

Not unlike the pandemics of yesteryear, COVID-19 has only made matters worse, creating a real estate gold rush for rural properties, with rental platform Vacasa naming Deep Creek the fourth best place in the country to purchase a winter vacation home in 2021, beating out Vermont and Montana.

“In a sense, the grandeur and the amenities of the turn-of-the century flipped from Deer Park to Deep Creek,” says White. “You know, we’ve never bottomed out up here. As one side declined, the other came up.”

At 69, she often wonders why John Work Garrett didn’t end up in the history books like other Gilded Age visionaries such as the Rockefellers and Vanderbilts. He died in his Deer Park cottage in 1884, during the hotel’s prime and just over a decade after the western county was named in his honor, before being laid to rest in Baltimore’s Green Mount Cemetery.

But even without great fanfare, his legacy does quietly live on in this far edge of Maryland, down the railroad tracks, along the ancient mountains of Appalachia, where White says plenty of people still go to get their water.

Just a short drive across the border near her home in West Virginia, cars line up at “the horse trough” on Caddell Mountain—an ever-flowing natural spring.

“It’s still part of the community’s mindset: that spring water is better for you,” says White. “It really hasn’t changed much. Society has, modes of travel have, thinking has, but what you’re looking for is still here—a piece of calm. The original tract was called ‘Peace and Plenty.’ And that’s where Deer Park was built.”