History & Politics

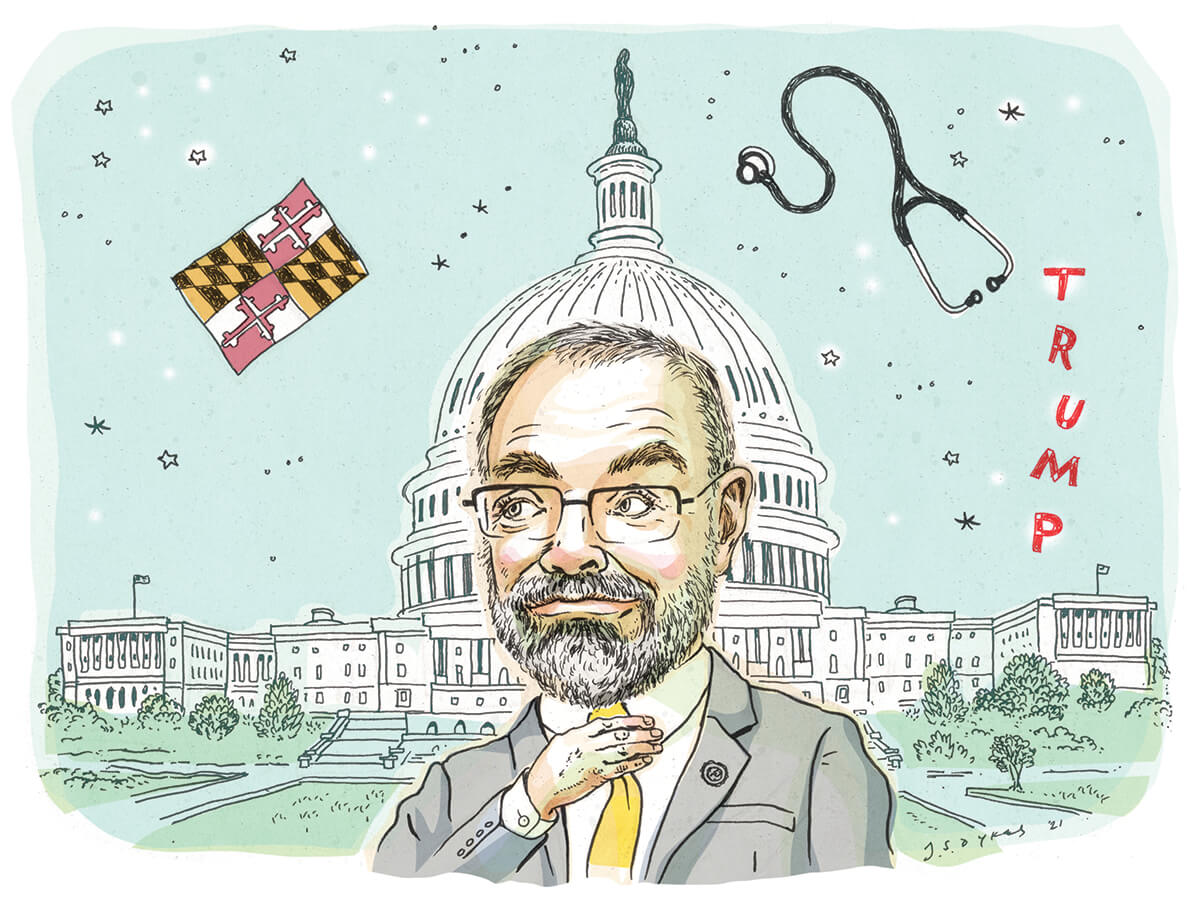

Does Congressman Andy Harris Represent the Future or End of the Maryland GOP?

To understand Harris' often out-there politics, you’ve got to understand the gerrymandering that enables him.

On January 6, as alarmed Americans were still grappling with the afternoon’s shocking images of the Donald Trump-inspired insurrection at the Capitol, a just-evacuated Andy Harris sat down in his House office for a virtual interview with WBAL-TV.

While waiting for word if Congress would reconvene to finish the certification of Joe Biden’s presidential victory, Maryland’s 1st District representative was calm. Disconcertingly so, given the day’s extraordinary and tragic events. Leaning back in his chair, Harris recounted witnessing Capitol police escorting House leaders “Mr. Hoyer, Speaker Pelosi, Mr. Scalise” off the floor. He matter-of-factly described being told that tear gas had been deployed in the rotunda and members of Congress should be prepared to use the emergency gas masks beneath their seats. He gave hint of a smile as he recalled the mob banging on the chamber door, comparing “the thumping” to the enthusiasm witnessed when a president arrives for a State of the Union.

“Obviously, later we heard there was a gunshot, but other than that,” Harris said, “there was no indication that this was a truly violent protest, as violent as one as you would worry about.”

Also disconcerting: While Harris said he didn’t support rioters breaking windows or disobeying lawful police orders, he stressed that he understood their frustration. He repeated Donald Trump’s debunked allegations that credible reports of election fraud had not been investigated and absolved the president of any role in fomenting the Capitol invasion. Instead, Harris—one of the Republicans challenging that day’s generally pro forma affair—placed blame with the summer’s Black Lives Matter protestors, whom he claimed had normalized violent political protest.

It went downhill from there.

After Congress reconvened, Harris got into a shouting match and near-tussle with a Democrat. During a Fox Baltimore interview the next morning, he spread the uncorroborated charge that leftist provocateurs were behind the Capitol assault. A week later, he skipped the House vote on impeachment altogether. A week after that, Capitol police stopped him after a handgun in his possession set off a magnetometer near the House chamber (a situation currently under investigation).

Not a good start to the sixth term of this GOP congressman who has said he will run next year? Not necessarily. Even with some Republican constituents joining Democratic officials in calling for his resignation, Andy Harris isn’t likely to pay a political price for his mounting controversies. The way his district is currently drawn, Harris’ stature in the eyes of his Trump-loving base might have only grown.

“The Democrats have no one to blame but themselves,” quips Richard Vatz, a conservative Towson University political analyst. In other words, to understand the often out-there politics of Andy Harris, you’ve got to understand the gerrymandering that enables him.

If it’s not obvious yet, Representative Andrew Harris is an anomaly in Maryland. He is the only Republican in the state’s congressional delegation and a Freedom Caucus member, the furthest right bloc in the House Republican Conference. (Founding Freedom Caucus members include Judiciary Committee member Jim Jordan, governor of Florida Ron DeSantis, and Mark Meadows and Mick Mulvaney, both of whom served as the former president Trump’s chief of staff.)

In one of the bluest states in the country, Harris’ stop-sign red district stretches from Assateague Island, up the entire Eastern Shore, and across the northern spine of the state to the Carroll County border of Pennsylvania. The result is that he has cruised to reelection since 2010 (which, to Vatz’s point, is basically how Democrats intended it when they crammed as many Republican precincts into the 1st District as possible).

On one hand, it would be easy to dismiss the 64-year-old Harris as a fringe politician in a hyperpartisan district. He’s a Cockeysville anesthesiologist by profession, and not particularly charismatic. He doesn’t hold any leadership positions. He hasn’t authored significant legislation outside of trying to prevent the legalization of marijuana in D.C. and generally only makes the news when his extreme-right positions place him outside even recent GOP norms.

It’s not a short list. He has expressed support for Hungarian dictator Victor Orban. He was the only House member to vote “present” on a resolution denouncing QAnon. He opposed naming a North Carolina post office after Maya Angelou, calling her a communist. (His politics often smack not just of Trumpism, but McCarthyism.) Unlike say, Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell, he continued to back Alabama Senate candidate Roy Moore after credible allegations of sexual abuse.

In recent years, he voted “no” on both funding for 9/11 first responders, which the House passed 402-12, and recognizing the mass extermination of Armenians under the Ottoman Empire, which passed the House 405-11. Closer to home, he denounced the CDC response to COVID as “a cult of masks” and railed against Governor Hogan’s closure orders at a ReOpen Maryland protest, comparing them to “Communist China” and North Korea.

In March, Harris voted against a resolution to award Congressional Gold Medals to police officers who protected the U.S. Capitol on Jan. 6. The measure, which Harris called “a stunt,” passed 413-12.

“Democrats have no one to blame but themselves,” says Richard Vatz.

What remains up in the air at this point, is whether the Old Line State’s Grand Old Party will continue lurching toward Harris and his Freedom Caucus wing and likely put itself out of business in terms of winning statewide office. Or, will it swing back toward Larry Hogan’s brand of traditional conservatism, which has proved capable of winning the most important elected office in Maryland? “The million-dollar question,” says Mileah Kromer, director of the Sarah T. Hughes Field Politics Center at Goucher College. It’s a divide analogous to the national GOP’s reckoning in the wake of former President Trump’s stinging election rebuke, the GOP’s loss of the U.S. Senate, and their standard bearer’s second impeachment.

Not surprisingly, given divisions within the GOP, different Republicans answer differently. State delegate and Minority Whip Kathy Szeliga, a former Harris chief of staff who lives in Perry Hall, remains all in on her former boss’ take-no-prisoners brand of politics.

“I’m launching a ‘Keep Harris in the House’ effort,” she told Baltimore in early March. Perhaps more noteworthy, Szeliga admits she’s given thought to running for Congress from the 1st District once Harris steps aside. “I don’t think Andy will be there another 20 years.”

Szeliga represents one direction for Maryland’s GOP and could conceivably run for governor sometime as well. “She would be a U.S. Senator if she lived in Alabama,” one veteran, non-partisan political observer says, paying a compliment, albeit a backhanded one, to her savvy political and communication skills.

Meanwhile, Harford County Executive Barry Glassman, closer in manner and rhetoric to Hogan, sees a potential opening to unseat Harris. Shortly after the events at the Capitol in January, he announced he’s weighing a run against Harris. The term-limited Glassman points to Harris’ oft-repeated campaign pledge not to run for more than six terms, which he recently disavowed, as a case study.

“The pledge he made is a popular one—‘I won’t stay in office more than 12 years and become a product of Washington’—but that’s exactly what has happened to him,” Glassman says. “I don’t know if he was always this conservative, and I wish I had another word, because I consider myself a conservative, or if he’s gotten more conservative since he’s been in Washington. But I feel it’s clear he’s become the very thing he said he was going to avoid by not seeking more than six terms.”

Harris did not make himself available for an interview for this story.

Heather Mizeur, a former State Delegate and talented campaigner with the ability to raise money, is the most prominent Democrat to throw her hat into the ring so far for 2022. But political observers across the board describe her task of upsetting Harris as a near- hopeless cause in the district as constituted.

It was not always this way in Maryland’s 1st District, or the state, for that matter.

For 18 years, Wayne Gilchrest, then a moderate Republican, represented the 1st District. Before him, Democrat Roy Dyson represented the area for a decade. But after Democrats remade the congressional map following the 2010 census, Harris has been untouchable.

The premise for the Democrats in creating the distorted district map was to boost their 6-2 advantage in the House to 7-1. They literally drew long-serving Western Maryland Republican Roscoe Bartlett out of the picture by adding a large portion of Democratic-majority Montgomery County precincts to his district.

Inconceivable today, 20 years ago Maryland’s congressional delegation was split 4-4. From 1993-2003, voters sent Republicans Wayne Gilchrest, Bob Ehrlich, Connie Morella, and Roscoe Bartlett to the Hill. Of course, it’s hard to imagine Gilchrest and Morella in to- day’s GOP. Gilchrest has switched party affiliations, and both were among more than two-dozen former Republican House members last year who announced they backed Joe Biden.

But even with Maryland’s 2-1 Democratic registration advantage, the state’s gerrymandering is crazy. Some Dems admit as much.

“It’s difficult to justify a 7-1 split in the congressional delegation,” says Len Foxwell, the veteran strategist who until recently served as the top adviser to Maryland Comptroller Peter Franchot and has since launched his own communications firm. “One downside is many people are disenfranchised from casting meaningful general election ballots.”

Change is hard, however, and power difficult to part with. Gerrymandering is built into our political DNA. The practice derives its name from a former Massachusetts governor named Elbridge Gerry. Described as “a nervous, birdlike little person” by a biographer, Gerry was both a signer of the Declaration of Independence and the brains behind the dubious legislation that created a misshapen political district in his home state in 1812.

The result is Harris has little incentive to appeal to the widest swath of voters. He can meet with a white supremacist on the Hill—he later said he didn’t know the man’s background—and call Christine Blasey Ford a “troubled woman” with “psychological problems,” without worry. In the past, as Gilchrest says, the 1st District, which used to include the Eastern Shore and Southern Maryland, shared a more libertarian bent and a concern for the Chesapeake Bay. Now, the 1st is represented by someone with a lifetime 3-percent score from the League of Conservation Voters.

Adding to the polarization in Maryland, as elsewhere, local jurisdictions are also gerrymandered. According to Foxwell’s research—he teaches a class around some of the wonky details at Johns Hopkins—more than 75 percent of Maryland’s jurisdictions are de facto monopolies. Baltimore’s 100-percent Democratic City Council isn’t the exception; it’s the rule here. In Montgomery County it plays out blue, but on the Eastern Shore and in Western Maryland, it’s a GOP-only show. “The result is an increasingly corrosive effect,” Foxwell says.

Harris has little incentive to appeal to the widest swath of voters.

Earlier this year, Hogan created an independent commission to address gerrymandering, but power rests in the Democratic legislature. Suffice it to say, Senate President Bill Ferguson quickly shot down the idea of a dramatic overhaul.

In the end, says Doug Mayer, Hogan’s former top communications strategist, Harris is less a cause than a symptom of what’s wrong with gerrymandering and GOP politics. For starters, he’d like to see a state map where four congressional seats are largely “safe” for Democrats, two for Republicans, and two up for grabs, reflecting the state’s party registrations. But he’s too much of a realist to be optimistic.

Mayer is similarly skeptical regarding any significant move away from Trump and Trumpism by the Maryland GOP or national GOP base and adherents like Harris.

“Donald Trump is the litmus test for Republicans,” says Mayer, now with the Annapolis-based Strategic Partners and Media, a highly regarded Republican campaign consulting firm. “As a long as the Republican Party stays a cult of personality, it’s going be a problem here and nationally to win.”