History & Politics

Turning Tides

After decades of silence, the Eastern Shore begins to reckon with its difficult history.

AN ORDINARY WEEKEND in downtown

Easton, the brick sidewalks are mostly empty,

save for the occasional local out for a stroll or a

handful of tourists taking in the iconic Colonial

architecture of Maryland’s Eastern Shore. With

only 16,000 residents, it’s the second-biggest town

on the peninsula, a quaint yet popular stopover

for folks from Baltimore and Washington, D.C., on

their way to Ocean City.

AN ORDINARY WEEKEND in downtown

Easton, the brick sidewalks are mostly empty,

save for the occasional local out for a stroll or a

handful of tourists taking in the iconic Colonial

architecture of Maryland’s Eastern Shore. With

only 16,000 residents, it’s the second-biggest town

on the peninsula, a quaint yet popular stopover

for folks from Baltimore and Washington, D.C., on

their way to Ocean City.

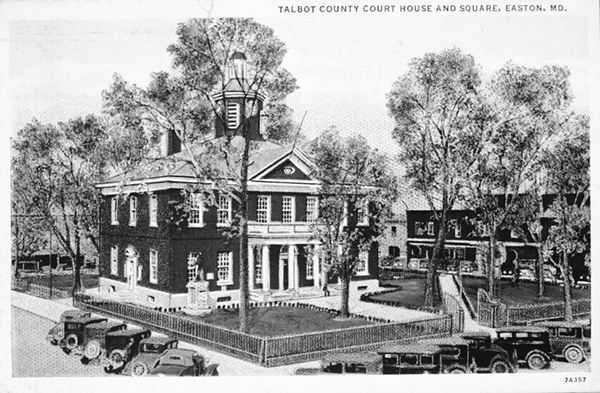

But on a Saturday afternoon this past August, a commotion could easily be heard from several blocks away as some hundred people gathered at the Talbot County Courthouse. Wearing masks and holding signs, their voices carried as they answered a call of “Whose courthouse?” with a unified “Our courthouse!” from a grassy lawn in front of the looming government building, built in 1794.

Talbot County Courthouse, circa 1920s. Courtesy of Talbot Historical Society.

Four days earlier, the Talbot County Council had convened inside the South Wing, sitting along a dark wooden bench separated by plexiglass dividers beneath the official seal of “Tempus Praeteritum Et Futurum,” or “Times, Past and Future,” as they voted on an issue that had grown increasingly urgent as months wore on. Earlier in the summer, after a thousand protestors rallied outside on Washington Street following the police killing of George Floyd, calls for Black Lives Matter quickly dovetailed with a demand to remove the “Talbot Boys.”

The Talbot Boys statue in December 2020.

In front of the courthouse’s grand entrance, the bronze statue, erected in 1916, depicts a young Confederate soldier carrying a Confederate battle flag atop a granite base that bears the names of 96 local Confederate soldiers and the inscription “1861-1865 C.S.A.,” or Confederate States of America.

“George Floyd’s death tugged at the conscience of this country, and people began to connect it to Confederate monuments and the messages that they send,” says Richard Potter, an Easton native and head of the local NAACP, who as a boy was mesmerized by the childlike soldier, sensing he must have done something special to receive such a significant perch, only years later becoming rattled by its history. “The courthouse is meant to be a place where we can go and get a fair and just trial. And yet to get inside, Black people have to walk past a monument that says you belong in bondage.”

Of course, this was not the first time that Easton residents had called for the statue’s removal. In 2015, Potter made the request after a white supremacist murdered nine people at the Emanuel African Methodist Episcopal Church in Charleston, South Carolina. Following a closed-door vote that violated Maryland’s open meetings law, the council unanimously chose to keep the statue where it stood. In 2017, calls came again after a white nationalist rally left one protestor dead in Charlottesville, Virginia. And again in 2020, when some 700 letters, including one from this writer, flooded the inboxes of the county councilmembers, as similar monuments came down all across the United States.

Protest at the Talbot County Courthouse, Easton, 8/15/2020

It was these events, and further conversations with community members, that inspired Council President Corey Pack to propose the removal of the Talbot Boys last summer, even after voting to keep it in 2015, at the time reasoning that it was a piece of history. “A man who fails to change his mind will never change the world that’s around him,” said Pack—the council’s first and only Black member—as the conversation grew contentious leading up to the vote that August evening.

Other council members—Chuck Callahan, Frank Divilio, and Laura Price—expressed opposition to the resolution, pointing to the COVID-19 pandemic, limited public input, and even the inability of the deceased Confederate honorees to be present. Price, in a previous meeting, also resisted the adoption of a diversity statement. “We have a lot of other problems here—I don’t think that this is one of them,” she said, referring to county government, though for many, speaking directly to the larger failure of the town, state, and country to reckon with its racial past and present.

In the end, the council voted 3-2 to keep the Talbot Boys—believed to be the last Confederate monument, outside battlefields and cemeteries, on public property in Maryland.

“The removal of this monument would not change the history of this county,” said councilmember Pete Lesher that evening. The local historian co-sponsored the resolution for removal, despite being a descendent of men listed on the statue’s base. “But the number who have expressed their feelings on this matter have made it clear that this is indeed a powerful symbol, and our actions on it tonight, I’m afraid, sadly speak of who we are now as a county, and the extent to which we have not yet changed.”

Within a matter of minutes, a protest emerged outside of the council’s windows, with demonstrators chanting, “Take it down,” “Vote them out,” and “Black Lives Matter,” causing the meeting to end early.

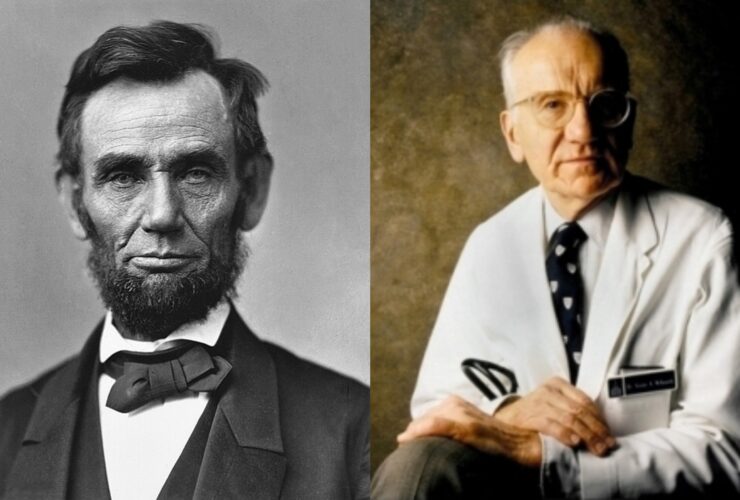

Council members Corey Pack, left, and Pete Lesher, right, inside the Easton courthouse.

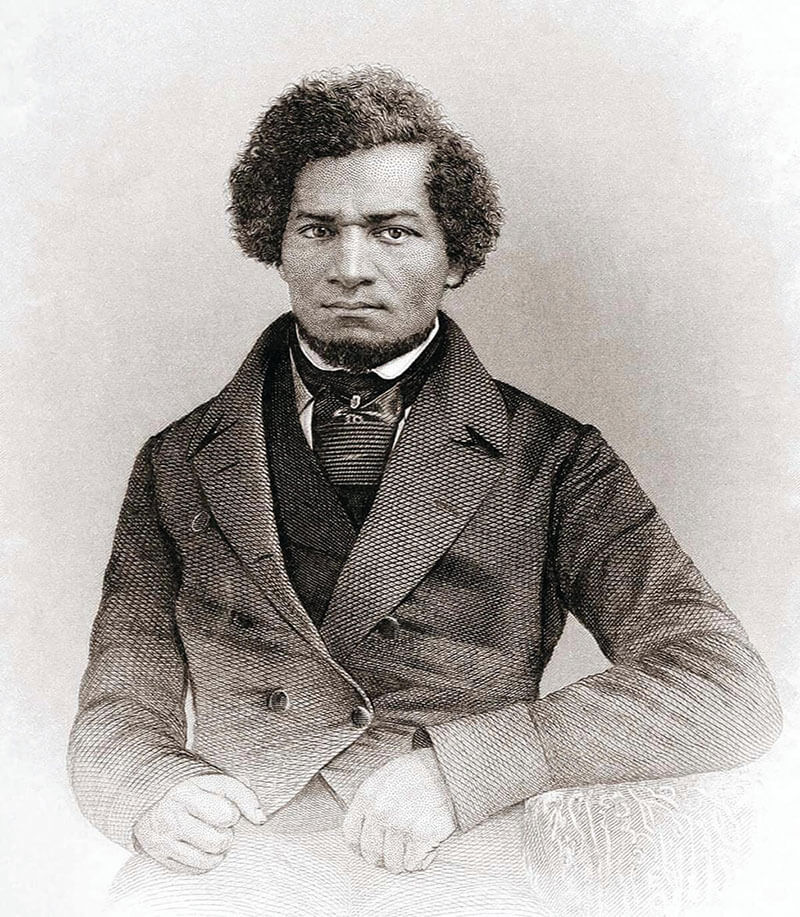

Frederick Douglass, circa 1855. Courtesy of THS.

A DECADE AGO, a different monument sparked debate in Easton—an increasingly sophisticated center of art and dining on the Eastern Shore. In 2011, a bronze statue of Frederick Douglass, arguably the region’s most famous son, was also erected on the courthouse lawn, but only after seven years of infighting, including objections from local veterans, and the margin of a single council vote, only under the condition that it not exceed the size of other statues, aka the Talbot Boys.

The famed abolitionist was long seen as a sort of balance to the Confederate soldier, whose cause sought to uphold slavery, as detailed in the C.S.A.’s founding documents. But today, the Douglass statue tells a broader story—his raised fist and defiant stance serving as a potent reminder of the horrors and hardships overcome by Black people in this town, and across the Eastern Shore.

Douglass was born into slavery around 1818, just 12 miles from where his monument now stands, becoming one of hundreds of enslaved African Americans on Wye Plantation, the largest of its kind on the Shore. “It was in this dull, flat, and unthrifty district . . . surrounded by a white population of the lowest order . . . and among slaves, who seemed to ask, ‘Oh! What’s the use?’ every time they lifted a hoe, that I . . . was born, and spent the first years of my childhood,” wrote Douglass in his memoir, My Bondage and My Freedom.

Corn crib at the Wye House plantation in Talbot County. Courtesy of THS.

In many ways, it can be said that the African-American experience began in this place, this region—on the Chesapeake Bay—when the first captured Africans arrived in Jamestown, Virginia, in 1619. But it wasn’t until changes in the trans-Atlantic slave trade and the expansion of tobacco plantations by the early 1700s that slavery took full root in Maryland. Tens of thousands of men, women, and children of African descent were brought by boat to tidewater ports that speckled these shorelines, tangling race and economics in a brutal web for centuries, particularly on the Eastern Shore—a 110-mile stretch of low-lying hinterlands separated from the rest of the state by the continent’s largest estuary.

By the time of Douglass’ birth, declining tobacco prices and overworked soil caused local farmers to shift to less labor-intensive grains, with many choosing to save money by hiring seasonal workers over supporting enslaved people year-round. Coinciding with a growing abolitionist movement that flourished in towns like Easton thanks to congregations of Quakers and Methodists, some slaves were released from bondage. But thousands of others were doomed to be sold from the Chesapeake to the booming cotton plantations of the Deep South as part of the Second Middle Passage, sometimes referred to as slavery’s Trail of Tears.

The Wye House plantation, circa 1892. Courtesy of THS.

On the Eastern Shore, these changes created a unique scenario, where the remaining enslaved people—some 35,000 in 1820—lived alongside some of the state’s largest populations of free Black people, and where some of the oldest African-American communities still stand today.

By its very nature, says Patrick Nugent, deputy director of the the Starr Center for the Study of the American Experience at Washington College in Chestertown, the Eastern Shore is in the middle of nowhere, but also in the middle of everywhere, close to urban centers like Baltimore, D.C., and Philadelphia, and yet isolated, geographically—with slavery in many ways at its historical center. For that, he says, to this day, “It is a crossroads of American politics, environments, and cultures that has led to a really complex history.”

In many ways, it can be said that the African-American experience began on the Chesapeake Bay, when the first captured africans arrived in Jamestown in 1619.

Loblolly pines in the Blackwater

National Wildlife Refuge in Dorchester County.

AND THAT INTERSECTION reached its apex leading up to the Civil War. Maryland’s below-the-Mason-Dixon-Line, border-state identity led to stark divisions of sentiments and sympathies, notably in rural communities like the Eastern Shore, where the economy relied on a racial caste system, with the local state legislature even considering secession in 1861. Ultimately, Talbot County sent more than 300 soldiers to the Union Army, but even after the Emancipation Proclamation, life changed slowly here, if much at all. Postwar “Black codes” and eventually Jim Crow laws kept wealth, resources, and power largely in the hands of white landowners, influencing housing, education, and employment for decades to come. Into the 20th century, African Americans often worked as low-wage farmhands and laborers in seafood-packing houses. Then Shore towns were hit hard by the Great Depression, still isolated from the rest of the state until the first Bay Bridge span in 1952, with that economic plight causing many to move away to industrialized cities throughout the Great Migration. Next generations would never return.

Women picking crabs and an oyster tonger. Courtesy of THS.

“I grew up in a middle-class environment, but I saw what other Blacks less fortunate than I had to deal with every day,” said Gloria Richardson of her life there in the 1930s and 40s during an interview with The Washington Post last December. A photograph of the young civil rights leader—pushing aside a National Guard bayonet during a 1963 demonstration over equal access for Black residents in Cambridge—remains an indelible image from that period. “Even today, until everyone is on the same plane, then the fight continues. This fight is still the same fight as before.”

Today, Dorchester County has a population of 32,000, more than 26 percent of whom are Black. But only 500 of the 2,800 businesses are minority-owned, and Black people are nearly twice as likely to be unemployed or living in poverty compared to their white counterparts. Those numbers are comparable, or worse, across the rest of the Eastern Shore, where school systems feature few teachers or principals of color, if any. Even after the Brown v. Board of Education decision in 1954, some counties did not integrate until 1969—the last in Maryland.

“We are concerned for our children,” says Adrian Holmes, founder of the Alpha Genesis Community Development Corporation in Cambridge, who is currently working to incorporate more diverse programming into the county’s public-school system. “We are not addressing this community with respect to its history. And so the ones who can find their way leave, and the ones who remain continue to struggle. We have to find more support for them, not just giving them money or housing, but addressing that systemic legacy.”

Politics also remain predominantly white—Somerset County elected its first Black politician in 2010—as does the judicial system, with courthouse ornaments like the Talbot Boys less symbolizing justice than serving as an icon of the old guard.

But 30 miles south of Cambridge in Salisbury, one historical marker dedicated to a Confederate general, considered a war criminal by historians, was removed last summer after more than 50 years. It had originally been installed in 1965—the same year that the Ku Klux Klan reemerged in Maryland after more than four decades, in Cecil County no less—on the site of a former historically Black neighborhood, which had been razed to make room for highways. In the 1980s, it was moved to the Wicomico County Courthouse, where slaves were once held, and a white mob lynched 18-year-old Garfield King in 1898, then Matthew Williams in 1931. In 2020, the metal plaque came down quietly with a final call from county executive Bob Culver, who succumbed to cancer a month later.

At least 40 of the more than 4,000 Black Americans lynched during the Jim Crow era were murdered in Maryland, with 11 on the Eastern Shore—a disproportionate share per capita. The state’s last recorded lynching took place in Princess Anne in 1933, when George Armwood’s gruesome killing was witnessed by as many as 2,000 white spectators, in part on the courthouse grounds, within sight of the region’s only historically Black college. Several lynchings took place in this most public square, as did one attempted lynching of Isaiah Fountain in 1920 at the courthouse jail in Easton, where he was ultimately hung. In each case, no suspects were ever found guilty.

STATE TROOPERS MEET AN ANGRY CROWD IN SALISBURY WHILE ATTEMPTING TO ARREST SUSPECTS IN THE 1933 LYNCHING OF GEORGE ARMWOOD. SEGREGATED SALISBURY CIRCA 1930S. COURTESY OF LIBRARY OF CONGRESS AND NABB RESEARCH CENTER, SALISBURY UNIVERSITY, RESPECTIVELY.

It was during this time, in the early 1900s, that the Talbot Boys statue was erected— half a century after the Civil War, amidst the box-office success of D.W. Griffith’s The Birth of a Nation, the revival of the Ku Klux Klan, and the violent rise of Jim Crow. Like these lynchings, its placement on the courthouse lawn—the epicenter of these small communities—was by no coincidence.

“None of these towns bears in its public space tangible evidence that it has acknowledged and come to terms with its racially violent history,” wrote Sherrilyn Ifill, president of the NAACP Legal Defense and Education Fund, in her book, On the Courthouse Lawn, in 2007. “The assumption of most whites is that this history is dead, unimportant, and irrelevant to the modern reality of life on the Eastern Shore. But in fact a town’s reputation as a racially violent one often lives on in the lore shared among Blacks.”

Tidal marsh in Blackwater.

ON THE EASTERN SHORE, the scales of history and heritage have long been tipped in the white direction, from the weathered complexion of the bay’s beloved watermen to its reputation as a verdant vacationland rooted in abundant agriculture, rarely with reference to the Black contribution to either. In fact, many outsiders (known as “come heres”) and residents (known as “from heres”) alike still don’t know that this region was once home to two Tuskegee Airmen, or a Buffalo Soldier, or the second president of Liberia.

But Clara Small, a retired Salisbury University history professor and Ph.D., is hoping to change that. “Blacks have never done anything in this country, and definitely not on the Eastern Shore,” a white student once told her. She went home that night and wrote 32 pages. Her third volume of Compass Points, a collection of African-American biographies from across the peninsula, is near release.

“I’ve always said that if you drop a compass here, and expand it 60 to 90 degrees, you’ll find homesites of the most important African Americans, not just on Delmarva, but in the state, in the nation, and sometimes internationally,” says Small, 74. “The Eastern Shore is one of the richest areas in this country in terms of African-American history. As a historian, I must footnote everything. My goal is to get the information out, so hopefully it gets passed on.”

A carte de visite of Tubman seated, circa mid-1800s.

During the days of slavery, the region’s sheer geography established a sense of isolation for African Americans—bookended by the bay and Atlantic Ocean, carved with a labyrinth of tributaries—but also channels of information. While traveling along the Chesapeake, visiting Black sailors helped spread news, as well as stories of freedom. And after one failed attempt landed him in the Easton jail, Frederick Douglass eventually fled north via train from Baltimore’s President Street Station—then hired out as a ship’s caulker—while disguised as one of these very seafarers.

On land, another important network connected them as well, including several key stops in Dorchester County, where the long, flat roads fall into inky black marsh, and the Eastern Shore’s most famous daughter was born around 1822. Today, numerous relics of Harriet Tubman appear between dying stands of loblolly pine along the Blackwater National Wildlife Refuge, from her likely birth site to her place of employment at the Bucktown General Store, plus other locations said to have been involved in the Underground Railroad, all now part of a 223-mile federal byway in her honor. Tubman famously returned to the Shore at least 13 times after her own escape to free more than 70 friends and family members. And these days, community members in nearby Cambridge plan to memorialize those heroic efforts by erecting her statue at the local courthouse—one block from the “Black Lives Matter” mural recently painted on Race Street, which was once the town’s unofficial dividing line.

The peninsula’s geography, bookended by the bay and atlantic ocean, established a sense of isolation for african americans, but also channels of information.

Bucktown General Store, where Harriet Tubman worked in Dorchester County.

Small was initially drawn to the Eastern Shore by a fascination with Tubman and Douglass, and her work has only become more relevant in recent years. The North Carolina native sees the racist mindsets of her former students persisting in towns like Salisbury, if not on the rise since the 2016 presidential election. She compares the Shore to Southern states like Mississippi, though the latter did willingly remove the Confederate symbol from its state flag last year. And yet it is not uncommon to still see that emblem here, flying outside of backwoods homes or brandished across the belt buckles and bumper stickers of certain white residents.

In this summer’s protests over the Talbot Boys, some young men protectively encircled the statue’s base, with one carrying just the red-and-white portion of the Maryland state flag—a symbol of the Confederacy. It wasn’t that many years ago, either, when in 1987, the Ku Klux Klan rallied on that same courthouse lawn in Easton, showing support for Tilghman Island residents who burned a cross into the yard of the town’s only Black family. Today, there are whispers of local Proud Boys.

“People might think it’s a thing of the past, but it still informs the present,” says Small. “The only place I’ve ever been called the N-word to my face is on the Eastern Shore—two times. I said preface it with ‘doctor.’”

Meanwhile, Salisbury’s Lynching Memorial Task Force is also working closely with city government to bring the region’s dark past into the light. This month, the group will install a plaque at the courthouse for the local victims, also honoring an unidentified Black man, whose burned body was discovered the morning after white residents dragged the deceased Matthew Williams behind a car through the streets of Black neighborhoods. And similar initiatives are underway all across the Shore and state via the Maryland Lynching Truth and Reconciliation Commission, established by the General Assembly in 2019.

“It took years to convince our local Black community to have this conversation because the wounds were still fresh,” says task force co-chair Amber Green, also noting that many lifelong residents had never even heard of the lynchings, which were largely ignored by the local press. (Damning coverage in national media, including the Baltimore Sun, inspired newspaper boycotts that cut off outside views well into the 1970s.) “There was a lot of hesitancy,” she continues. “There are still living relatives of Matthew Williams, and of the man who he was accused of murdering. But we continued to push the message that domestic terrorism has a direct result in our country’s, and county’s, disparities. A lot of people just assume that the past is the past, get over it. But all of it is connected.”

As the founder of the nonprofit Fenix Youth Project, Green helped lead the four-year effort to remove the town’s Confederate marker last summer, and is now spearheading a racial justice essay contest for local students. Following George Floyd’s death, she was also part of numerous marches that filled the streets of Salisbury. Within weeks, Broad Street, chosen for its proximity to the courthouse, was renamed Black Lives Matter Boulevard.

“We are in 2021, and we have been talking about the same issues since the 1930s, the 1960s,” says Green, 30, who nonetheless sees a course correction coming. “I don’t hope for change, I expect it.”

View through the trees of a mural painted on the side of the Harriet Tubman Museum in Cambridge.

ON THE SURFACE, at least, the prospect of change seems especially apparent in Chestertown, where in 1882, Gordon Wallace’s great-great grandfather was one of the men who founded Sumner Hall, a veteran’s post for Black Union soldiers. More than 400 Black Kent Countians fought for the Union, as documented in a granite monument downtown, much like the founders of Unionville, located on the way to the Wye Plantation in Easton, who are laid to rest in the cemetery behind St. Stephens A.M.E. Church.

Marker declaring Unionville a “historic African-American community settled by ex-slaves and free Blacks.”

Wallace now works at Sumner Hall, which reopened as a museum and education space in 2014 after decades of disrepair, and through relationships made there, he helped design two street murals in support of racial justice this summer, just around the corner on the town’s main thoroughfare.

“At the time, murals were popping up in other states, and I thought it was pretty cool that we were going down that path,” says Wallace, 23. “It was a good way of starting the conversation. Everyone can interpret art on their own time. Though I was a little surprised by the initial pushback.”

He’s referring to the three-hour meeting in August, where members of Chestertown’s majority-white council were hesitant to adopt the murals— one in the heart of the historic downtown to read “Black Lives Matter,” and a second, four blocks north in the Black neighborhood of Uptown, stating “We Can’t Breathe.”

Cemetery behind St. Stephens A.M.E. Church in Unionville.

The mayor cited concerns such as potential legal exposure, long-term maintenance, and the possibility of vandalism. (Threats did roll in from a Facebook group called the Kent Island Patriots in nearby Queen Anne’s County. “I’ve got some big fat tires I’ve been waiting to burn off,” said one member.) Meanwhile, some residents felt the effort was little more than white guilt from the town’s many liberal retirees. But in the end, after a slew of public comments, both were unanimously approved, adding the tagline “Chestertown Unites Against Racism” to each.

Where the downtown mural is now painted, High Street follows leafy brick sidewalks past Georgian- style homes with historic bronze plaques before ending at the Chester River, a bustling slave port until as late as 1770. Over the next nearly two centuries, like elsewhere on the Shore, the legacy of slavery would take on new forms, like segregated restaurants, theaters, schools, and hospitals, with Blacks and whites still living in separate silos across the county today.

At the same time, these African-American communities became sources of great pride, with a vibrant Black business district downtown on Cannon Street through the first half of the 20th century. Here, a Black entrepreneur sold square-foot lots to his neighbors, ultimately affording them the right to vote. Meanwhile, in Uptown, a Black school was named after Henry Highland Garnet, an internationally known abolitionist born into slavery in Kent County, while Charlie Graves’ Uptown Club became a destination on the “Chitlin’ Circuit,” drawing acts such as James Brown and Ray Charles.

Much of the old African-American neighborhoods have succumbed to gentrification or been replaced by affordable housing, but the Bethel A.M.E. and Janes United Methodist churches, past which Freedom Riders marched in 1962, are still anchors, with roots to the 1800s.

“This is a place where, in the face of all of this systemic oppression, African-American communities were able to build churches, businesses, schools—and those legacies still exist to this day,” says Nugent of Washington College, where he is also director of Chesapeake Heartland, an African-American humanities project in collaboration with the Smithsonian’s National Museum of African American History and Culture. “One is hard-pressed to find that type of deep-rooted legacy, dating back to the 1600s, elsewhere across the United States.”

A grassroots-style initiative, Chesapeake Heartland is working to document local Black life here, centering the often untold stories of African-American resilience, achievement, and excellence over the adversity. The program’s recently acquired “humanities truck” will serve as a mobile museum at events around the Shore, while their digital archive, launching this month, will feature a collage of oral histories and archival materials.

“African-American history on the Eastern Shore has been channeled through a few singular heroes, but that larger, complex, more nuanced story has not been fully recognized,” says Nugent. “Douglass and Tubman were geniuses, but they were also members of communities, and their success in so many ways came out of the other men and women who grew those networks, which brings out a notion that’s much more interesting. Not just that these two incredible people rose, but the shoulders of giants that they stood on.”

Images from the Chesapeake Heartland digital archive.

Courtesy of Chesapeake Heartland.

In September, Chestertown released a 16-month anti-racism plan that includes an apology for slavery, the establishment of an equity advisory committee, and offical support for existing community efforts. Those include Sumner Hall’s Legacy Day celebration of African-American culture, the Black Union of Kent County’s Juneteenth festival, which launched last year around the town fountain, and the James Taylor Lynching Remembrance Coalition, which seeks to memorialize a 23-year-old Black man lynched by a white mob near the Kent County Courthouse in 1892.

“When everything happened [last] summer, my uncle was telling me about the civil rights movement,” says Wallace. “It made me look back for comparisons between what happened then and what’s happening now. And in a Malcolm X speech, he mentioned Gloria Richardson. He said it would be these small communities, these rural areas, that would step up and make change when they say, ‘we’re here.’ Knowing everything that happened on the Eastern Shore makes this different. That is what makes this real.”

Notably, the police department has also revised its “use-of-force” policy to include a duty to intervene. The Eastern Shore has not escaped the plague of police-related deaths of Black people in modern-day America.

In 2018, 19-year-old Anton Black, who was born in Chestertown, was killed under the weight of three law enforcement officers outside of his mother’s home in nearby Caroline County. This past December, Black’s family filed a federal lawsuit alleging excessive force by officers and ensuing efforts to cover up those actions by public officials, as it would take an entire year for the cop, Thomas Webster IV, to lose his certification, only after it was revealed that he failed to disclose dozens of use-of-force reports from his previous post in Delaware. And this year, after failing to advance last session due to COVID-19, lawmakers also plan to reintroduce Anton’s Law, which would require more transparency and accountability from Maryland police departments.

Black’s death, brutally captured on body-camera footage and so similar to that of George Floyd’s, is what sparked Wanda Boyer, a Chestertown native, to lead the effort to install those local murals, along with fellow town activists Arlene Lee and Maria Wood. “Being so close to home, the illusion was over, it was time for us to do something,” says Boyer, 57, who grew up in the Uptown neighborhood. “From the beginning, I knew that even if the murals didn’t get passed, they would at least start some conversations. But it’s also about bringing action . . . I am cautiously keeping hope alive. All we’ve had is hope.”

“He said it would be these small communities, these rural areas, that would step up and make change when they say, ‘we’re here.’”

Mural painting in Chestertown. Courtesy of Shore Studios.

“BACKWARDS” HAS LONG BEEN a term used to describe this landscape of backroads and backwaters—in many ways, justly so, as many of these small towns still feel stuck in something closer to the middle of the 20th century than 21 years into the 21st. On the Eastern Shore, past remains prologue, and decades of silence leave old wounds unhealed.

“No racial reconciliation process can succeed without providing [the] opportunity for truth-telling,” wrote Ifill in On the Courthouse Lawn. “But merely providing victims and their descendants the opportunity to tell their stories is not enough. The stories must be heard. It is in the telling and hearing of formerly silenced stories that communities can recreate themselves.”

In the weeks following the Talbot Boys vote, a group of concerned citizens formed in Easton to hold regular rallies on the courthouse lawn during the county council’s Tuesday night meetings. Its members sought financial pledges from community members to fund the statue’s removal—they’ve raised at least $40,000 thus far—as well as a site for its relocation, though the local cemeteries and historical society are not interested.

Fredrick Douglass statue in Easton.

During the winter months, they circulated bright yellow yard signs that read “Move Talbot’s Confederate Monument” in capital letters (which were quickly countered by pro-statue placards declaring “Preserve Talbot History”), and began efforts to engage political leaders on state and national levels. A separate, community-led Racial Equity Task Force of Talbot County also plans to release a report on inequities across a variety of local sectors.

As of early January, the Talbot Boys statue still stands, with the council members who voted to keep the Confederate monument suggesting that the issue be pushed to an unlikely ballot measure in 2022. Both Corey Pack and Pete Lesher feel that the decision should ultimately be left to them as elected officials, and hold out hope for a change of heart among their colleagues, who did not return requests for comment.

“Those statues cannot speak words, but they do speak volumes,” says Pack. “If the elected body ever reaches a point that it can say, ‘This statue no longer represents what we believe in as citizens of this county,’ it still doesn’t remove the stain. You never remove that history. But what a strong symbol to the community, that we are moving collectively in the right direction, in an area where so much history has taken place. That’s a great American story to be told.”