The Gritty History (and Gentrification) of Fells Point

Baltimore City annexed Fells Point some 250 years ago this month, but the waterfront neighborhood has an epic story all its own.

By Ron Cassie

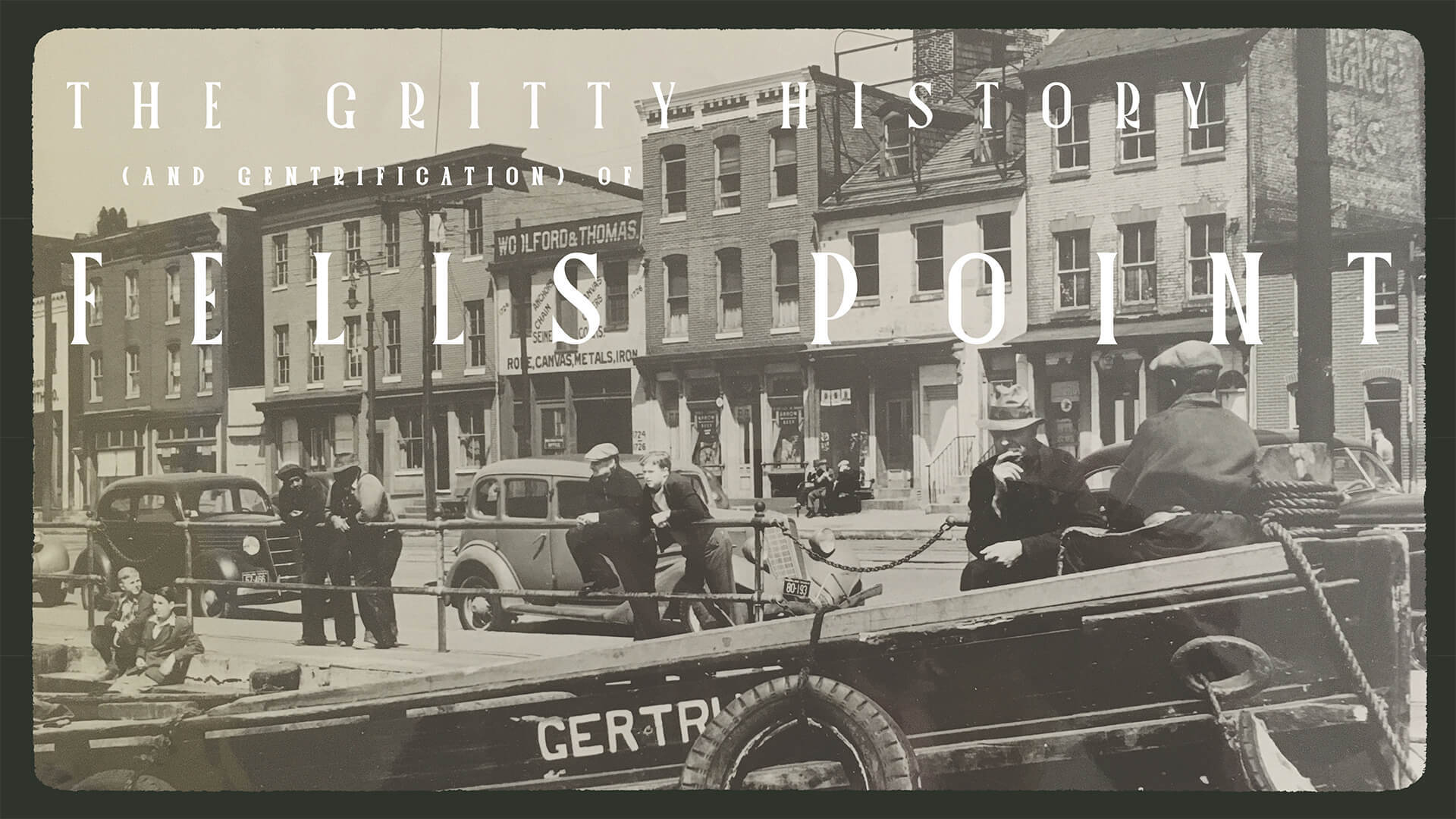

Opening photo: Thames Street, foot of Broadway, May 1940. —Courtesy of Tony Norris

THE OUTBREAK OF WAR IN 1812, a disconcerting letter from Capt. Richard Moon to the Secretary of the Navy was reprinted in The Weekly Register, a Baltimore-based magazine among the most widely read of its era.

Referring to himself as the “[former] commander of the privateer Sarah Ann,” Moon reported his Baltimore-commissioned schooner had been captured. Worse, Moon wrote, the British claimed six members of his crew were, in fact, treasonous subjects of the king and “are to be tried for their lives.” Among those imprisoned was George Roberts, described as “a coloured man and seaman” and someone Moon knew to be born in the U.S., married, and living in Baltimore. Only following further correspondence between diplomats did the seamen escape execution.

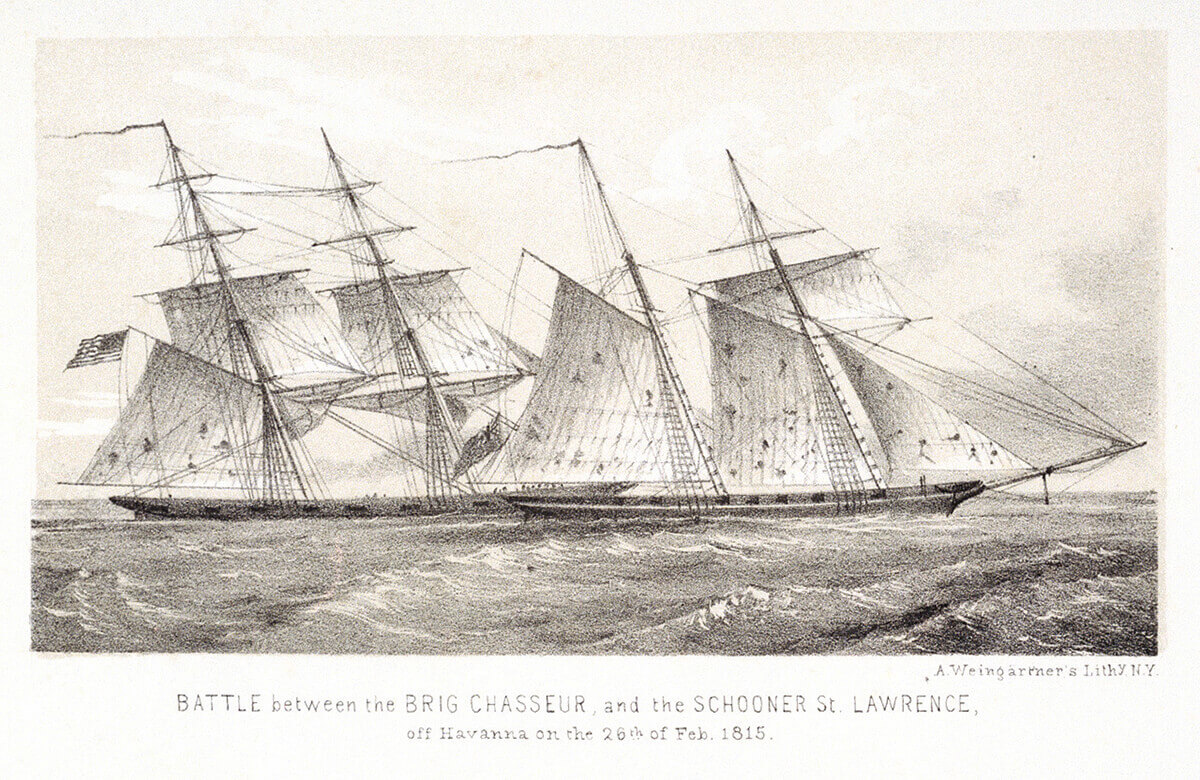

After his release from a Jamaican prison, Roberts continued to fight the British on the high seas, signing on as a gunner aboard the Chasseur. Newly constructed in the shipyard of Thomas Kemp at the corner of Washington and Aliceanna in Fells Point, the topsail schooner quickly became the best-known of the swift Baltimore clippers. In 1813, the Chasseur raided six British vessels, sending all but one up in flames when they were finished. The following year, its crew, including Roberts, divested another dozen and a half British merchant ships of their cargo, the spoils shared among its captain, seamen, and shipowner. (During war, the difference between pirates and privateers depended upon one’s perspective. Governments in need of naval help sanctioned the often lucrative, if risky, seizure of its opponent’s vessels by normally illegal means.)

The Chasseur, from which the popular Southeast Baltimore bar takes its name, also became famous for boldly proclaiming a single-handed blockade of the British Isles. In total, the Fells Point docks were home to 58 such privateering vessels, credited with the capture of more than 500 ships. The attempted British invasion of the Baltimore harbor in the fall of 1814 (think “Star-Spangled Banner”) was in good measure to rid the “nest of pirates” from Fells Point.

When the Chasseur returned and saluted Fort McHenry after the war’s end, its crew were hailed as heroes. The already legendary schooner was dubbed the “Pride of Baltimore.” Its ship’s captain, the renowned Thomas Boyle, who had lost men in battle and had been wounded himself, praised Roberts for displaying “the most intrepid courage.” Readjusting to civilian life as a free Black carpenter and laborer, the ex-privateer purchased a home for $150 on Ann Street in Fells Point. Such was Roberts’ reputation, that over the ensuing decades, despite the horrific racism of the era, he marched in uniform alongside the city’s prominent citizens on civic occasions. His 1861 obituaries—he lived to 95—recalled his patriotism, “many hair-breath escapes,” and desire to always be remembered as “one of the defenders of his native city should the necessity have arrived [again] to take up arms in its defense.” His “brave character,” it was noted, was “adorned with amicable [and charitable] disposition,” such that “news of death will cause heartfelt sorrow.”

Battle

between the

Chasseur, a Fells

Point privateer, and

British schooner

St. Lawrence off

Havanna, 1815. —Adam Weingartner, public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Roberts’ service was not unique, however. It’s estimated 20 percent of the War of 1812 privateers were African American. Other Black Americans, free and enslaved, worked in Fells Point’s busy shipyards, building the vessels that undid the British navy and merchant fleet. (In a terrible irony, they were also forced to caulk ships used in the foreign and domestic slave trade.)

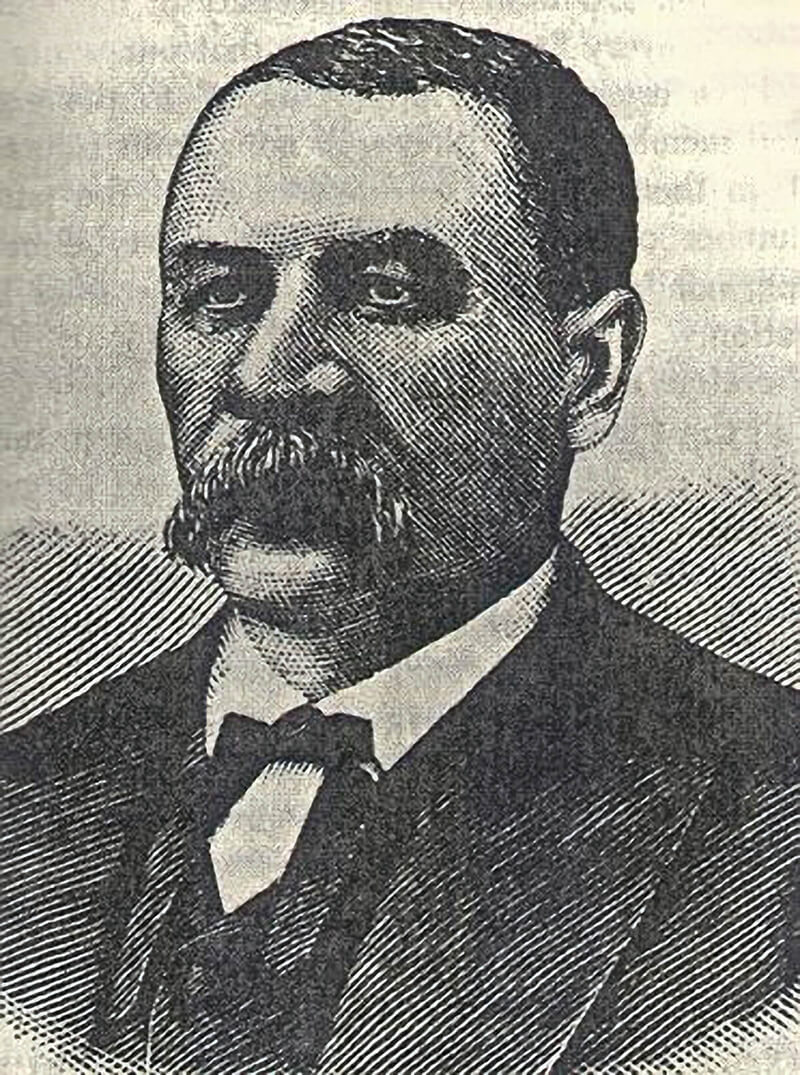

Free Black seaman and a hero of the War of 1812, George Roberts —Courtesy of the Maryland Center for History and Culture, PVF

It’s no coincidence the Caulkers Association, one of the first Black trade unions in the U.S., was formed in Fells Point or that a Black former ship’s caulker named Isaac Myers founded the Chesapeake Marine Railway and Dry Dock Company in Fells Point, a cooperative that employed 300 workers at its peak. Nor is it a coincidence that Frederick Douglass learned to read and write in Fells Point and escaped slavery posing as a free Black sailor. The same month that Douglass escaped from Fells Point, 133 people of African descent were shipped from Baltimore to New Orleans for enslavement on Louisiana plantations.

Some 250 years ago this month, on the cusp of the American Revolution, Baltimore City annexed both nearby Jonestown and Fells Point, taking its early shape. But from its clipper ships and compelling Black history to its yellow fever outbreaks and child labor horrors; from its boarding houses, brothels, and bars to its inflow of Polish immigrants and landmark “Stop the Road” battle; from its rebirth in the 1970s to its ongoing gentrification—the iconic waterfront neighborhood with its “Belgian block” cobblestone streets has a gritty, colorful, complicated story all its own.

And let’s not forget the tales of sailors getting shanghaied from Fells Point pubs; or the tattooed, hard-drinking, blacksmith and ward boss George Konig Sr., whose election-day street fights with the Know-Nothings in the 1850s were straight out of The Gangs of New York; and a certain bar where Edgar Allan Poe is said to have had his last bender. Its narrow lanes and alleyway are filled with secrets and stories.

Fells Point reflections. —Video by J.M. Giordano

he hamlet that sprouted on the small,

hook-shaped peninsula on the northwest

branch of the Patapsco River was on land

purchased by Quaker William Fell, who

followed his brother Edward here from Lancashire,

England. It’s a bit confusing because all the male Fells

seem to be named either William or Edward, but it was

William’s son Edward, a colonel in Maryland’s provincial

army, who first laid out the budding town’s streets

in 1763. The Fell family cemetery, awkwardly squeezed

today between rowhouses on Shakespeare Street, contains

the remains of William Fell, his son, Edward Fell,

and his son, William. (There was no Admiral Fell. The Admiral Fell Inn, it's been said, takes its name from an episode

about a drunk admiral, not named Fell, stumbling into

the harbor—“the admiral fell in.” Management at the inn

has changed hands since it opened in 1985 and says the

name is merely a play on words, but it’s too good of a story

not to repeat.)

he hamlet that sprouted on the small,

hook-shaped peninsula on the northwest

branch of the Patapsco River was on land

purchased by Quaker William Fell, who

followed his brother Edward here from Lancashire,

England. It’s a bit confusing because all the male Fells

seem to be named either William or Edward, but it was

William’s son Edward, a colonel in Maryland’s provincial

army, who first laid out the budding town’s streets

in 1763. The Fell family cemetery, awkwardly squeezed

today between rowhouses on Shakespeare Street, contains

the remains of William Fell, his son, Edward Fell,

and his son, William. (There was no Admiral Fell. The Admiral Fell Inn, it's been said, takes its name from an episode

about a drunk admiral, not named Fell, stumbling into

the harbor—“the admiral fell in.” Management at the inn

has changed hands since it opened in 1985 and says the

name is merely a play on words, but it’s too good of a story

not to repeat.)

Early Fells Point developer, Ann Bond Fell. —Courtesy of the Maryland Center for History and Culture, 1986.105.4

Edward Fell advertised his plan to sell plots of his land near “Baltimore-Town, Maryland on a Point known by the Name of Fell’s-Point” a year earlier in the old Maryland Gazette. Grammarians will note the apostrophe after the family name, which has dropped out of general use, but not without heated debate over the years. More importantly, it was not Col. Edward Fell who ultimately developed the wooded, 100-acre lot he inherited on the water and the surrounding 3,000 acres he consolidated. He died at 33. Rather, it was his first cousin and wife, Ann Bond—once described as “the Jim Rouse of her day”—who sold the plots.

Wealthy in her own right, Ann Bond Fell proved a shrewd businesswoman. She vigorously promoted Fells Point, which was competing with Baltimore Town for investment. She fended off gossipy attacks in the local broadsides and rumors of unhealthy water in Fells Point. She also struck up forward-thinking contracts, which stipulated that purchased property would revert to her if not developed within two years. (The City of Baltimore might take a cue from Ms. Fell in its dealings with developers and slumlords.) She later remarried a well-to-do county landowner, but not before she made him sign a prenuptial agreement, ensuring her holdings would be passed down to her children.

18th-century Fells Point street map. —Courtesy of the Society for the Preservation of Federal Hill and Fell’s Point.

If it isn’t obvious yet, the neighborhood street names—Ann, Bond, Fells, as well as Lancaster, Thames, Shakespeare, Aliceanna, Caroline, Bank, Gough, Wolfe, and Washington— date to this 1700s period, marking “The Point” as one of the oldest active waterfront communities in the country. Fleet Street, it’s believed, pays homage to Capt. Henry Fleet, a British Chesapeake Bay explorer. Other names have changed. Wilk Street, now Eastern Avenue, was known as “the Causeway”—a notorious stretch of “houses of ill-fame” frequented by sailors. Market Street became Broadway, which since 1786 has been home to one of the city’s oldest public markets.

The names of Fells Point’s lively alley streets have changed, too. Though not necessarily for the better. Strawberry Alley, home to the Methodist church attended by Frederick Douglass as a young man, became Dallas Street. (Douglass later returned and built five rowhouses on the street, including one available on Airbnb, that remain to this day.) Happy Alley became Durham Street, which today is full of murals and mosaics celebrating the girlhood home there of Billie Holiday. The alliterative Argyle and Apple Alleys were renamed Regester and Bethel Streets.

The rebranding of the “alleys” to “streets” after the Civil War might be considered the first attempt at gentrification in Fells Point.

The leveling of two majority-Black alley streets—sections of Dallas and Spring, part of a “slum clearance” effort on the edge of Upper Fells in the late 1930s—might be the second. They were demolished to make room for white immigrant families—in what became the Perkins Homes housing project. Recently, the majority Black residents of Perkins Homes have been moved out and the low-rise Perkins buildings have been knocked down in favor of a new mixed-use development, which is supposed to include a percentage of housing that is affordable for its former tenants.

Pay day for the stevedores, c. 1905. —Library of Congress

emarkably, the streets of Fells Point, like

many in the earliest years of the city,

were not formally segregated during its

so-called “golden era,” which peaked

with the War of 1812 and lasted until the Civil War.

(Baltimore’s infamous housing segregation law,

which stated that no Black resident could move onto

a block in which the majority of the residents were

white and vice versa, came in 1910.) All seven of the

residential alleys in Fells Point had white and Black

households, as Mary Ellen Hayward, author of Baltimore’s

Alley Houses, discovered when she examined

the city’s first directory to note “householders of color”

in 1808. Eight of the larger streets, too, were at least somewhat integrated with Black caulkers, laborers,

laundresses, blacksmiths, barbers, and their

children—a trend Hayward traces through subsequent

directories. When Douglass, known as Frederick

Bailey as a boy, lived in Fells Point with the

slave-owning Auld family, “a [nearby] German baker

had a shop on the southwest corner of Aliceanna

and Happy Alley,” Hayward writes, “but there was

also a ‘colored grocery’ on the same block.”

emarkably, the streets of Fells Point, like

many in the earliest years of the city,

were not formally segregated during its

so-called “golden era,” which peaked

with the War of 1812 and lasted until the Civil War.

(Baltimore’s infamous housing segregation law,

which stated that no Black resident could move onto

a block in which the majority of the residents were

white and vice versa, came in 1910.) All seven of the

residential alleys in Fells Point had white and Black

households, as Mary Ellen Hayward, author of Baltimore’s

Alley Houses, discovered when she examined

the city’s first directory to note “householders of color”

in 1808. Eight of the larger streets, too, were at least somewhat integrated with Black caulkers, laborers,

laundresses, blacksmiths, barbers, and their

children—a trend Hayward traces through subsequent

directories. When Douglass, known as Frederick

Bailey as a boy, lived in Fells Point with the

slave-owning Auld family, “a [nearby] German baker

had a shop on the southwest corner of Aliceanna

and Happy Alley,” Hayward writes, “but there was

also a ‘colored grocery’ on the same block.”

Two of the oldest wooden homes standing in Fells Point, at 612 and 614 Wolfe Street, became homes to Black caulkers in the 1840s and 1850s. All during these decades, as tobacco receded as an economic driver in Maryland, the free Black population in Fells Point and Baltimore grew dramatically.

Two of the more unlikely stories of the period involve a self-taught Black artist named Joshua Johnson and a French-speaking Black Cuban immigrant named Elizabeth Clarisse Lange, both of whom lived in Fells Point. Born into slavery, Johnson, became an accomplished and sought-after formal portrait artist and is recognized as the first African-American professional painter in the United States. Lange, meanwhile, is under consideration by the Vatican for canonization. From 1818 to 1828, with fellow immigrant Marie Magdelaine Balas, she offered previously unavailable free education to children of color out of her Fells Point home. Later known as Mother Mary Lange, she founded the first permanent African-American religious order of nuns, the Oblate Sisters of Providence, and the school that evolved into Saint Frances Academy in East Baltimore (and recently graduated the 2023 NCAA Women’s Basketball Tournament Most Outstanding Player, Angel Reese).

But even with the presence of Douglass, who, at about 12 years old, purchased his first book, The Columbian Orator, from Nathaniel Knight’s bookstore on Thames Street—perhaps worth consideration as Baltimore’s first radical bookshop—it is not correct to view Fells Point through the lens of slavery and abolition, says local Black historian Lou Fields.

Black maritime business owner Isaac Myers, c. 1875. —LIBRARY OF CONGRESS

“The proper lens is economic, it’s about the building of Baltimore, and because the Inner Harbor is naturally shallow and Fells Point has a deep water port, that’s where life gets started,” says Fields, who has been leading Douglass tours of Fells Point for 23 years. “At that time, it was a maritime community. Everybody was working to make a dollar, a quarter, or whatever it was.” He notes that some of the first whites to come to Baltimore from Europe were indentured servants: “The first Blacks who came to The Point, like the first whites, came to supply a labor force to clear land, build houses, and build roads.” Landowners found they were more suited to the work than the Indigenous people—Baltimore is part of the ancestral land of the Susquehannock and Piscataway tribes—so they brought in more enslaved people from the Eastern Shore and Southern Maryland.

“That said, Frederick Douglass’ life changed dramatically because he was sent to Baltimore,” continues Fields. “He might not have survived otherwise. But once he’s here, he also sees Black men, women, and children auctioned off at the foot of Broadway and others separated from their families and put on ships headed to New Orleans.”

Eventually, Douglass joins the East Baltimore Improvement Society on what is now Durham Street, where he gains some education from older free Black ship caulkers and meets his future wife. There were physical confrontations between white workers and Black workers for jobs on the docks—and Douglass nearly gets killed when he’s attacked by several men—but he also writes about a pair of Irish immigrants who encourage him to escape.

“The light broke in upon me by degrees. I went one day down on the wharf of Mr. Waters; and seeing two Irishmen unloading a scow of stone, I went, unasked, and helped them,” recalls Douglass in his 1845 memoir. “When we had finished, one of them came to me and asked me if I were a slave. I told him I was. He asked, ‘Are ye a slave for life?’ I told him that I was. The good Irishman seemed to be deeply affected by the statement. He said to the other that it was a pity so fine a little fellow as myself should be a slave for life. He said it was a shame to hold me. They both advised me to run away to the north; that I should find friends there, and that I should be free.”

“Fells Point is a place with a lot of history, a lot of issues, a lot of different people from all walks of life thrown together in a tight geographic area,” Fields says. “It’s the most fascinating neighborhood in the city.”

Local historian

Lou Fields stands next

to the Frederick Douglass

memorial sculpture.-Photography By J.M. Giordano

y the 1960s and into 1970s, much of Fells

Point was set for demolition. Viewed by city

leadership as a waterfront slum, Fells Point

was deemed better to pave than preserve.

The shipbuilding yards had disappeared with the

advent of the steamship, which required a deeper channel

than even Fells Point offered. The canning industry,

which overlapped and then replaced the shipbuilding

industry and once filled more than a hundred packing

houses around the harbor, had all but disappeared as

well, following longer growing seasons and a booming

trucking industry to the south and west.

y the 1960s and into 1970s, much of Fells

Point was set for demolition. Viewed by city

leadership as a waterfront slum, Fells Point

was deemed better to pave than preserve.

The shipbuilding yards had disappeared with the

advent of the steamship, which required a deeper channel

than even Fells Point offered. The canning industry,

which overlapped and then replaced the shipbuilding

industry and once filled more than a hundred packing

houses around the harbor, had all but disappeared as

well, following longer growing seasons and a booming

trucking industry to the south and west.

Tugboats at Fells Point, circa 1950s.—Photography by Tom Scilipoti

Rukert Terminals on Brown’s Wharf remained one of the last surviving cargo warehouses in operation. The toxic Allied-Signal chromium plant in now-rebranded Harbor Point was still a major employer. However, there were few others beyond the sprawling H&S Bakery plant.

Synonymous with Fells Point since 1878, Baker-Whiteley’s tugboats remained a daily sight on the water, echoing the past as the neighborhood’s future became the subject of intense debate, activism, and lawsuits. (The tugboats would leave, too, in the early 1980s, moving to Locust Point after the New York-based McAllister Brothers acquired Baker-Whiteley. In general, port business didn’t so much leave Baltimore as migrate further out around the harbor from Fells.)

Meanwhile, transportation planners laid out an east-west expressway across Lancaster Street to connect I-70 in the west to I-83 in the center of Baltimore—with I-95 east of Fells Point, one of the final pieces of Maryland’s interstate network.

The city told residents the highway was inevitable, and their rowhouses and businesses stood in the way of progress. With few options, many took the marketpriced checks and relocation fees and left, some happily no doubt, for the suburbs. Whole blocks, almost a hundred homes and structures in all, were condemned to make room for a massive interchange over today’s Harbor East and a six-lane, elevated highway through the heart of Fells Point’s historic district.

It was in the middle of the Fells Point “Stop the Road” citizen uprising in 1972 that Tony and Laura Norris stumbled across a dingy bar called The Lone Star among the vacant rowhomes and dilapidated boardinghouses. Both were musicians and teachers, but Laura had gotten ill and couldn’t work for a period and while they were figuring out what to do next, a friend ventured to Fells Point looking for office space. Unable to find anything suitable, a realtor pointed him toward a small saloon for sale. “He came back and said, ‘Let’s buy a bar,’” the now-82-year-old Tony Norris recalls. “So, I called a Baltimore friend who was in California teaching, and said, ‘Loan me $3,000,’ or whatever it was for the down payment. At that time, you could buy almost everything in the neighborhood. I think we paid $14,000 for the liquor license and the building, but there wasn’t much there. There was an old room in the back that had a kitchen that had never been finished. One of our customers who was handy said, ‘Well, I’ll help fix the kitchen up.’”

Among some junk and antiques in a midtown garage, Norris found a stained glass window dedicated to the memory of a mysterious Bertha E. Bartholomew, which went on display with back lighting behind the bar. That memorial window provided the inspiration for one of the city’s beloved institutions of the past half-century, and most well-traveled bumper sticker ever—EAT BERTHA’S MUSSELS.

From top: Bertha’s

owners Laura and Tony Norris

in front of their beloved

bar and restaurant today; the memorial stained glass

window and the inspiration

for the name of Bertha’s.—PHOTOGRAPHY BY J.M. GIORDANO

When Bertha’s opened, a few other bars changed hands and an otherwise-declining neighborhood—that easily could have gone the way of Philadelphia’s waterfront community, which had recently been waylaid for I-95—became invigorated by an unlikely youth movement.

Which isn’t to say there weren’t colorful old joints or neighborhood stalwarts that stuck around. There were always a lot of bars (and complaints about bars) in Fells Point, the nature of an old port of call. Helen’s Corner, run by Helen Christopher, whose merchant marine husband had been lost at sea, catered to tugboaters. Now the Admiral’s Cup, Christopher sold it in 1985 with the stipulation she could continue living upstairs for the rest of her life. Jimmy’s Restaurant, a greasy spoon and gathering spot for shift-workers and politicians alike, had been around since the late ’40s. The Acropolis night club, owned by the same Greek family, featured belly dancing. Miss Irene’s at Thames and Ann—home to The Point today—remained a smokey, rough-around-the-edges bar with cheap beer, a big pool table, and hard-drinking regulars.

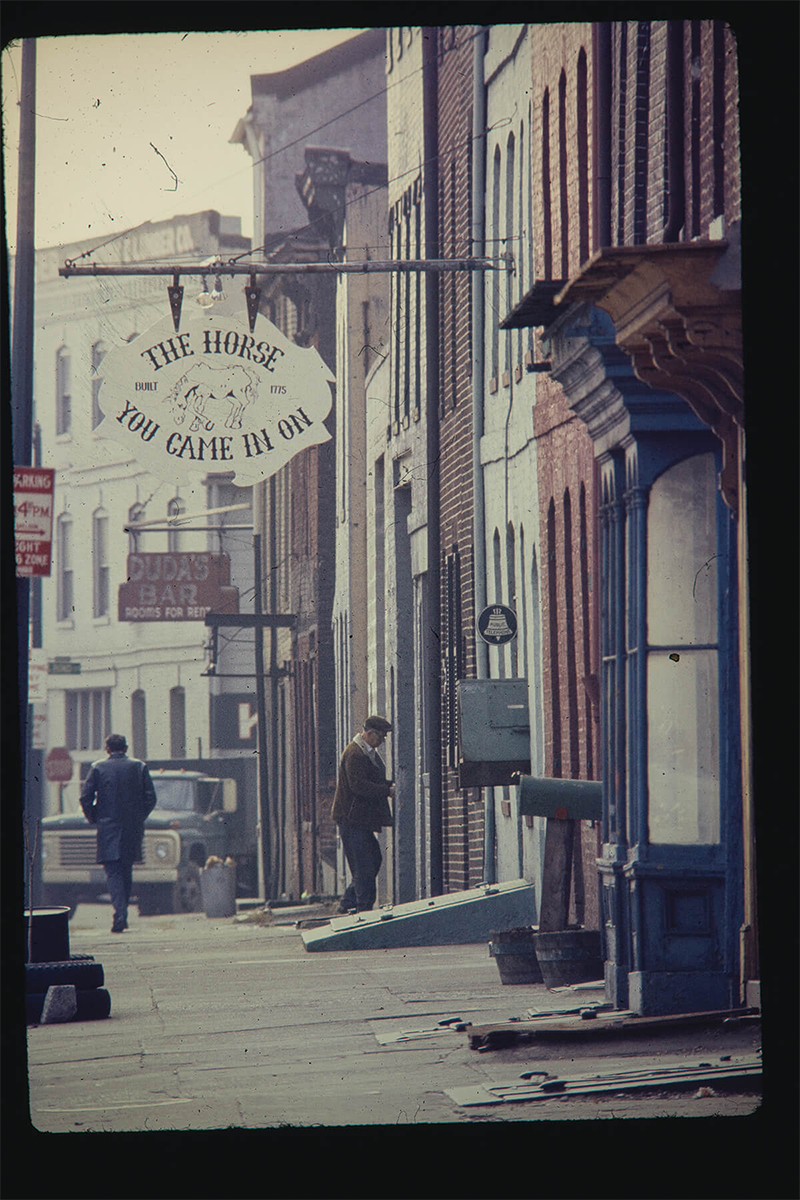

Leadbetters

Tavern, the Cat’s Eye

Pub, and The Horse You Came In On in the 1970s.—COURTESY OF THE SOCIETY FOR THE PRESERVATION OF FEDERAL HILL AND FELL’S POINT

But The Thames Café (“Thames and Dames”) got sold and remade as Leadbetters Tavern, named after the blues musician Lead Belly. A well-known Baltimore figure named “Turkey” Joe Trabert opened Turkey Joe’s a few doors from Bertha’s. A 1775-built tavern called Al’s and Ann’s on Thames Street was rechristened The Horse You Came In On in 1972, after a long-haired, twentysomething named Howard Gerber bought it with a down payment won at Pimlico. Things were a bit looser in those days. The day that The Horse You Came In On opened, a friend of Gerber’s literally rode a horse through the front door and up to the bar. Some believe the saloon is not only the oldest continuously operating bar in the U.S., but also the last stop of Edgar Allan Poe before he was found delirious in the street on Election Day 1849. (One theory holds Poe’s death resulted from a Mobtown practice known as “cooping,” in which eligible voters were kidnapped, drugged, or forced to drink, and then disguised to cast multiple ballots.)

In 1975, Irish-American Kenny Orye, who convinced some he ran guns for the IRA, and Tony and Ana Marie Cushing opened the Cat’s Eye Pub on Thames Street, taking their name from a West Virginia distillery where Orye’s uncle bought his moonshine. Contrary to what’s been published elsewhere, Ana Marie Cushing says with a smile, the previous Harbor View tavern there had not been a biker hangout, but a lesbian bar. By the late 1970s and early ’80s, the Cat’s Eye’s back room had become a place to be after closing time, recalled Steve Bunker, a former seaman who operated the nearby China Sea Trading Company with a parrot perched on his shoulder. “At 3 a.m. you could run into politicos, hookers, sailors, deal-makers, illegal Irishmen, riffraff, and refugees,” Bunker, who now lives in Maine, wrote years later in the Fells Point newsletter. “You didn’t ask too many questions about your stool mates, you just drank your beer, passed a joint, and enjoyed the company.”

Before Orye died from an overdose at 33 in 1987, he organized an Irish wake at the Cat’s Eye for a departed IRA leader. It was equal parts publicity stunt to raise awareness for the IRA cause and joke on city officials and the press: The body in the casket wasn’t real. Five years after Orye’s death, longtime Cat’s Eye bartender Jeff Knapp, who normally resembled Abe Lincoln and once snuck into the St. Patrick’s Day parade dressed as the patron saint of Ireland, was honored with a New Orleans-style jazz parade for his funeral.

Ghost tours of Fells Point claim the ghosts of Orye and Knapp still work the Cat’s Eye bar.

The music and bar crawl culture developed over time as more pubs opened kitchens and got permits for live music. But things were not excactly popping in the early ’7os. “When [Bertha’s] first opened, someone would say, ‘Let’s go over to The Horse or the Cat’s Eye for a beer’—there was this sense we were all in it together—and you’d get into your car and drive around the corner and have no trouble parking right in front,” the now-84-year-old Tony Norris says. “It was that empty down here.”

Dreamlander Edith Massey in front of her store, Edith’s Shopping Bag.—EAST BALTIMORE DOCUMENTARY PHOTOGRAPHY PROJECT COLLECTION. SPECIAL COLLECTIONS, UNIVERSITY OF MARYLAND, BALTIMORE COUNTY.

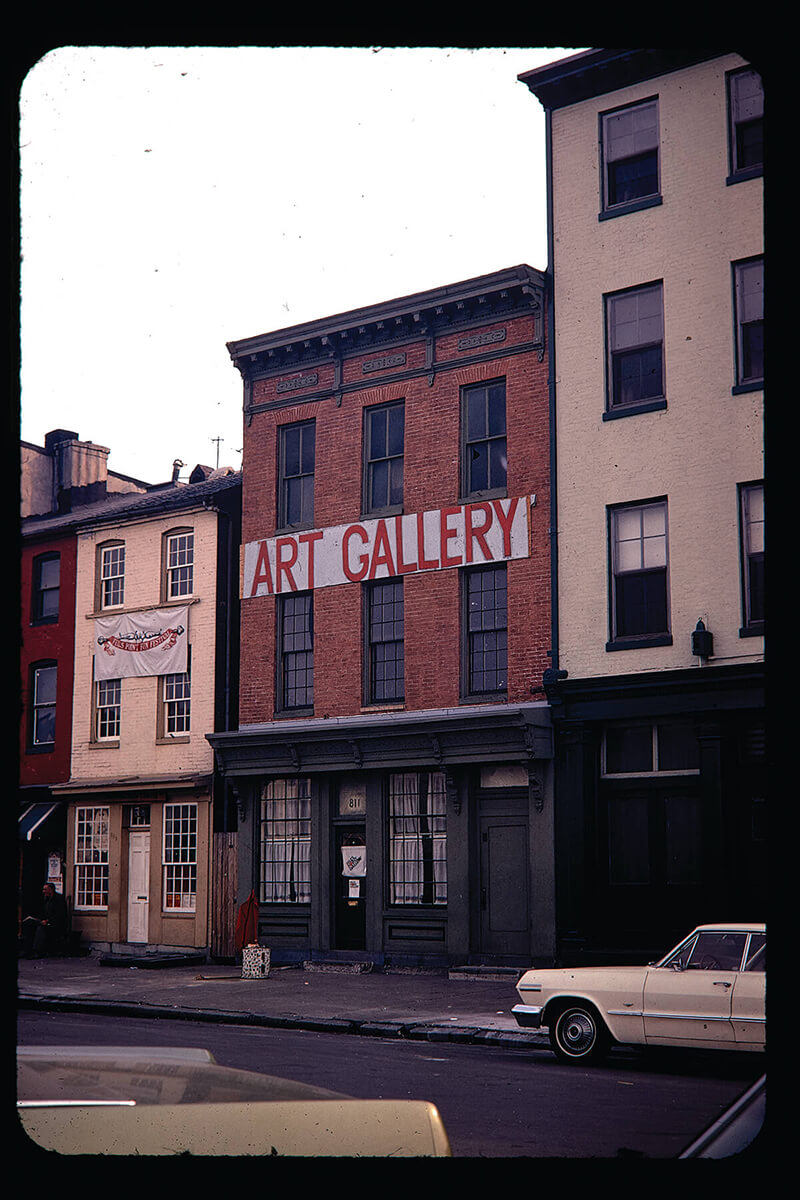

The Fells Point art scene had begun blossoming earlier. By the late ’60s, the old Hollywood Bakery on Broadway had turned into a full-blown artist colony of former Maryland Institute College of Art students. Divided into 22 rooms and studios, the entire place rented for $100 a month, giant bakery ovens included. Others began squatting in and renting previously condemned houses from the city while the “Stop the Road” fight continued in the courts. By 1973, at least 15 houses that the city had bought out earlier were rented to people who wanted to live in and repair them. A $7,500 home went for $75 a month with the generous provision that repair materials could be deducted from the rent—the nascent start of a now-50-year rehabbing movement.

The Fells Point Gallery, founded in 1969 by MICA alumni, became a destination. Then, a second-hand bookstore opened. Many still looked down upon “seedy” Fells Point at the time, but others saw it as Baltimore’s version of Greenwich Village. The Fells Point Corner Theatre, now in Upper Fells, raised its first curtain, appropriately, at the corner of Shakespeare and Broadway in 1970. The still-thriving Vagabond Players moved into the former Corral’s Bar on Broadway in 1974.

In the late ’60s, John Waters, Glenn Milstead, aka Divine, and friends began making pilgrimages to Fells Point, finding new partners in subversion. MICA graduate Vincent Peraino, who was among the influx of artists, became Waters’ set designer. Susan Lowe, a painter who later dated Orye (some of her paintings still hang in the Cat’s Eye), appeared in nearly every Waters film. Other Fells Point Dreamlanders included Mink Stole, George Figgs, Paul Swift, Peter Koper, and Bob Adams. “The Hollywood Bakery, that was Vincent’s commune, and it was right next door to Pete’s Hotel, where Edith Massey worked as a bartender and we hung out,” Waters recalls with a laugh. “It was the worst possible time down there and it was the cheapest possible place. Drinks were 30 cents. Divine hated it. He called it a ‘hobo bar.’”

Waters shot all over Fells Point and Massey opened a thrift store, Edith’s Shopping Bag, with Adams following her memorable appearance as “the Egg Lady” in Waters’ 1972 movie hit, Pink Flamingos.

“Fells Point was welcoming to all kinds of people, that was the thing that was so amazing,” Waters continues, noting he once did a fashion shoot at the Apex adult movie theater on Broadway, which somehow coexisted among the churches and families in Upper Fells. “Paul Swift would jump up and dance naked on the bars. They weren’t gay bars. It was gay and straight. It was trans. Trans even then, and everybody really got along. It was just cultural outlaws that didn’t fit in their own minority.”

“The artists would hang around with the tugboat guys and stevedores in the bar—we used to open at 8 a.m. for guys getting off their night shifts—that’s just how it was then,” says Cushing.

Fells Point

Fun Festival, late 1960s,

with a “Stop The Road”

banner hanging on the

side of a building.—COURTESY OF THE SOCIETY FOR THE PRESERVATION OF FEDERAL HILL AND FELL’S POINT

The Art Gallery building, c. late 1970s.—COURTESY OF THE SOCIETY FOR THE PRESERVATION OF FEDERAL HILL AND FELL’S POINT.

At the same time, pioneering preservationists had moved to Fells Point. One visionary was Lu Fischer, who lived in Ruxton and was married to a doctor but bought a waterfront rowhouse with intentions of restoring it, unaware a highway was planned through her block. “Perhaps no other town on the eastern seaboard boasts 18th-century houses facing the water such as we have here in Fells Point,” she wrote in a letter to The Sun in 1966. Former Councilman Tom Ward helped found the Society for the Preservation of Federal Hill and Fell’s Point the following year. Bob Eney, who’d grown up in Dundalk before a stint in the Army and a career as a department store display artist in New York, was another champion. Photographing and documenting some 200 homes and buildings, Eney led the successful campaign to get Fells Point listed on the then-new National Register of Historic Places in 1969—the first inclusion from Maryland—wooing officials with walking tours, drinks, and dinners at Haussner’s in nearby Highlandtown.

According to Eney, one of then-Vice President Spiro Agnew’s female staffers, who secretly supported the Fells preservationists, passed their completed National Register forms to Agnew to speed approval. Not realizing the obstacle that placement on National Register would present to the highway he and local contractors favored, Agnew dutifully forwarded them on and “in three days we were on the National Register,” Eney recalled in 2004. “The contractors [who’d been bribing him for years] were furious with Agnew because he was so dumb. He had no idea what he had done.”

The annual Fells Point Fun Festival, in fact, was first organized as an anti-highway fundraising effort. At the 1969 annual street party, Barbara Mikulski, a then-33-year-old social worker, shouted her opposition as future Mayor William Donald Schaefer tried to make his case for the highway. “The British couldn’t take Fells Point, the termites couldn’t take Fells Point,” announced Mikulski, part of group calling themselves Radio Free Fells Point. “And we don’t think the State Roads Commission can take Fells Point either.”

The granddaughter of Polish bakers, Mikulski is a link between Fells Point’s long immigration history and the fight to the stop the highway. “My great-grandmother landed in Fells Point somewhere at ‘the foot of Broadway,’ which is what we called that area then, not Fells Point,” Mikulski says. “When she came to this country and lived on Chester Street near Holy Rosary, she could read, but she was from Poland. One of the things she did to learn English was to buy a newspaper and go down to the Broadway Market and practice the language and the exchange of money, and so on. People were helpful and she could trust that she wasn’t going to be taken advantage of. The churches were like settlement houses because they were bilingual.”

Prior to the Eastern-European wave, Fells Point was the arrival station for thousands of farmers and laborers from Germany and Ireland. St. Patrick’s Church, now serving a Spanish-speaking congregation on Broadway, is the city’s oldest Catholic parish, dating to 1792. Germans came to Baltimore early and often, with many fleeing their homes after the failed 1848-1849 revolution. The Irish, in the 1840s and 1850s, arrived as refugees, some in desperate condition as they were pulled onto the Fells’ docks from vessels known as “coffin ships” because of the number who succumbed during the Atlantic crossing.

But by the 1870s, Poles were the dominant immigrant group. The first Roman Catholic Polish parish—St. Stanislaus Kostka on South Ann Street—formed in 1880. The city’s first Polish newspaper launched in 1891. A second parish, Holy Rosary Church, where Sunday morning Mass is still said in Polish, was founded in 1887. St. Casimir’s in Canton was founded in 1904. Which is not to romanticize the immigrant experience. Women—and children—went to work in the Fells canneries and as seasonal laborers on Maryland farms. Mikulski later bought a house on Ann Street in part, she admits, because it was in the path of the highway. “She was ready to lie down in front of the bulldozer,” says Tony Norris, the Bertha’s owner, who has known Mikulski since the early ’70s. The Norrises subsequently traded rowhouses with Mikulski and remained a neighbor for 20 years. When she was elected to Congress in 1976, her Eastern Avenue office was only steps from her grandparents’ bakery.

“It was a great neighborhood because people tended to live, work, worship, and shop in the same area,” says Mikulski, who was born in 1936 and retired from Congress in 2017, after becoming the first woman to chair the powerful Senate Appropriations Committee.

“In terms of the battle of ‘the Road,’ there was the parochial crowd, the preservationists, [artists], the business owners—we were all in it. Were the town hall meetings contentious?” Mikulski adds. “It’s Bawlmer, hon.”

Barbara Mikulski

giving a speech.—EAST BALTIMORE DOCUMENTARY PHOTOGRAPHY PROJECT COLLECTION. SPECIAL COLLECTIONS, UNIVERSITY OF MARYLAND, BALTIMORE COUNTY.

The fundamental problem behind the conception of “the Road”—including the stretch known as “The Highway to Nowhere” that got built through majority-Black West Baltimore—is officials did not appreciate the value of working-class neighborhoods, Mikulski says. “That was certainly the attitude of Robert Moses,” the New York highway builder who first designed Baltimore’s planned east-west highway. “He did not see the value, he didn’t see the jobs that were there, and he didn’t see what I call the social capital. It was the relationships that were, and are, important in those communities.”

The artifacts, both living and dead, of those Polish roots are all over. Sophia’s Place, a Polish deli selling stuffed cabbage, among other specialties, continues in the renovated Broadway Market, as does Ostrowski’s Polish deli on Bank Street. Patterson Park’s monument to Gen. Pulaski, a Revolutionary War hero, and the Katyn Memorial in Harbor East hardly need mention.

Eventually other groups came, though situated farther from the waterfront. After World War II, there was a huge migration of Lumbee Indians from North Carolina into Upper Fells. The Baltimore American Indian Center on Broadway was founded in 1968. And, of course, all up and down Broadway and Eastern are dozens of Mexican and Central American businesses and restaurants.

Cocina Luchadoras,

Sophia’s Place, and

Cat’s Eye Pub.—PHOTOGRAPHY BY J.M. GIORDANO

It’s ironic perhaps, but ever since “the Road” though the Fells “slums” was defeated for good in the late ’70s, gentrification has been a sensitive subject.

By 1985, former warehouses and factories were already being turned into expensive apartments. “Speculators see Fells Point as an opportunity,” Bunker, the former owner of the China Sea Trading Company, said in a Sun story.

“It’s just not the same,” Manuel Alvarez, a chief engineer for the departed Baker-Whiteley tugboat company, told the same reporter, adding he had little desire to visit Fells Point anymore. “It’s just too...trendy. It’s not just the way it used to be.”

In an oral history a generation later, Ed Kane, who founded the Baltimore water taxi operation in the ’70s, said he thought Fells Point “still doesn’t know what it wants to be when it grows up.” It’s been in “state of transition,” he said, for “more than 200 years.”

A ghost sign reading “Vote Against Prohibition” remains visible today.-PHOTOGRAPHY BY J.M. GIORDANO

Gentrification remains a concern for some of the older folks who recall places like Leadbetters, which was sold in 2016, and the Wharf Rat, which was one of the oldest buildings and bars in the city when it was sold in 2021. They say the original English character of its zigzagging streets and tiny pubs is all but gone.

Duda’s Tavern, in a storied Thames Street building that once boarded sailors, is still a family-run operation after more than 70 years. The Norrises, however, are in the process of selling Bertha’s.

A Starbucks has opened, and the Atlas Restaurant Group continues to buy up property and open bars and restaurants, raising questions about Fells Point losing its idiosyncratic touches. Some worry the H&S Bakery plant will leave and be replaced by a highrise office or condo complex like those in Harbor East—where height restrictions were lifted in the 1990s for the subsequent development projects.

The numbers speak for themselves: The median home price in Fells Point rose from $77,600 in 1990 to $349,650 in 2014. The percentage of residents with a BA degree or higher was 33 percent in 1990 and 70 percent by 2014.

With gentrification what often comes is a loss of what sociologists call “third places,” where people spend time between home and work. First United Evangelical, an 1851 German church on Eastern Avenue, for example, is now luxury apartments. The 96-yearold Patterson duckpin alleys are currently under conversion to condominiums—though some lanes may remain after a protest.

However, the 19th century St. Michael’s Church in Upper Fells is now a brewpub and the former St. Stanislaus today hosts a yoga and fitness studio—21st century “third places.” There are others, like the cozy Greedy Reads bookstore, which opened in 2018.

Six years ago, the upscale Sagamore Pendry hotel on Thames opened inside the long-vacant, recreation-pier building—once home to the fictitious headquarters of the Baltimore Police Department in the ’90s show Homicide: Life on the Street.

The question may be, does it matter whether Fells Point residents know the Pendry was first constructed as a $1 million—a pricey sum in 1914—dual-purpose maritime warehouse/state-of-the-art ballroom and recreation center for the Fells immigrant community?

Is preservation still a rallying point and part of the glue that binds the Fells Point community together, and if so, for how long?

Society

for the Preservation of Federal Hill

and Fell’s Point president David

Gleason sits in front of the

1765-built Robert Long House.-PHOTOGRAPHY BY J.M. GIORDANO

“When I was a kid, it was a different world, we didn’t have all these cars, these high-rises and yeah, a lot of houses were vacant,” says 46-year-old Andy Norris, who took over running Bertha’s from his parents and lives in Upper Fells. “My parents would say, ‘Go outside and play,’ and I’d take a ball and beat the ball against a vacant house and then three other kids would be hanging out with me and we’d play a game of some kind.

“I get the new business owners and the changes,” Norris continues. “I don’t hate it, like a lot of the oldtimers. They’re coming from a good place. In their minds, they’re doing the best thing that they can do for the neighborhood. I believe that. Now, is it the best thing for the neighborhood? I don’t know. The thing about Fells Point is that had so much character, and characters, such charm. But people got older and sold their places and the new people, who are buying them, this is how they see their future.”

Norris acknowledges the water and rowhouses will be always be here. As will reappointed warehouses and Thames’ Belgian block streets. But what else? “What I guess I mean, is that a neighborhood or is that just brick and stone?”