History & Politics

Gov. Wes Moore Has Lofty Dreams for Maryland. Can He Make Them Come True?

Through no fault of his own, Moore is essentially starting over in the General Assembly against suddenly stiff, worse than first projected, headwinds.

By Ron Cassie

Photography by Mike Morgan

OMENTS BEFORE THE Baltimore Orioles finally signed a long-term lease in December, Mayor Brandon Scott reminded officials and gathered press inside Camden Yards’ six-floor conference room that he never doubted the team and state would reach an agreement. “I spent the last few years explaining one thing to the media,” Scott said, before paraphrasing Jay-Z. “That I have 99 problems, but the Orioles leaving Baltimore, leaving Camden Yards, is not one of them.”

Seated across the room, Gov. Wes Moore crinkled his nose, broke into a broad grin, and nodded back at the mayor. Scott in his remarks went on to praise Moore and his team and O’s CEO John Angelos and his team. But the governor had stopped smiling by then. Hanging awkwardly in the air was the fact that 12 days from its expiration date, the Orioles’ lease and the threat of their departure had become an issue for Moore.

On the very night the O’s clinched the American League East title with a 2-0 win over the Red Sox, Moore and Angelos stood together in a luxury suite and celebrated to huge cheers as a scoreboard statement announced a 30-year deal to keep the Orioles in Baltimore. Except, the deal wasn’t done. Birdland had been misled for a photo op. Fans learned the next day that a memorandum of understanding, not a 30-year lease, had been reached. It wasn’t quite a full-blown PR stunt. It wasn’t former Gov. Larry Hogan standing on the BWI tarmac alongside $11 million of useless South Korean COVID tests, but O’s diehards didn’t appreciate their emotions being played with on the biggest night at Camden Yards since Delmon Young’s bases-clearing double in Game 2 of the 2014 ALDS. Partly because Angelos had long ago alienated the fan base and notoriously doesn’t speak to the local press, Moore took the brunt of the blowback.

After a honeymoon General Assembly session last year, the lease negotiations provided Moore’s first protracted test in office. Senate President Bill Ferguson and Comptroller Brooke Lierman, fellow Democrats, signaled they were not going to become rubber stamps for the popular new governor. They wouldn’t sign off on a quid pro quo, refusing to hand development rights to the taxpayer-owned warehouse and historic Camden Station to the billionaire Angelos family in exchange for a long-term deal. Ultimately, a 15-year lease got inked, which will extend to 30 years if Angelos and the state reach a separate development agreement.

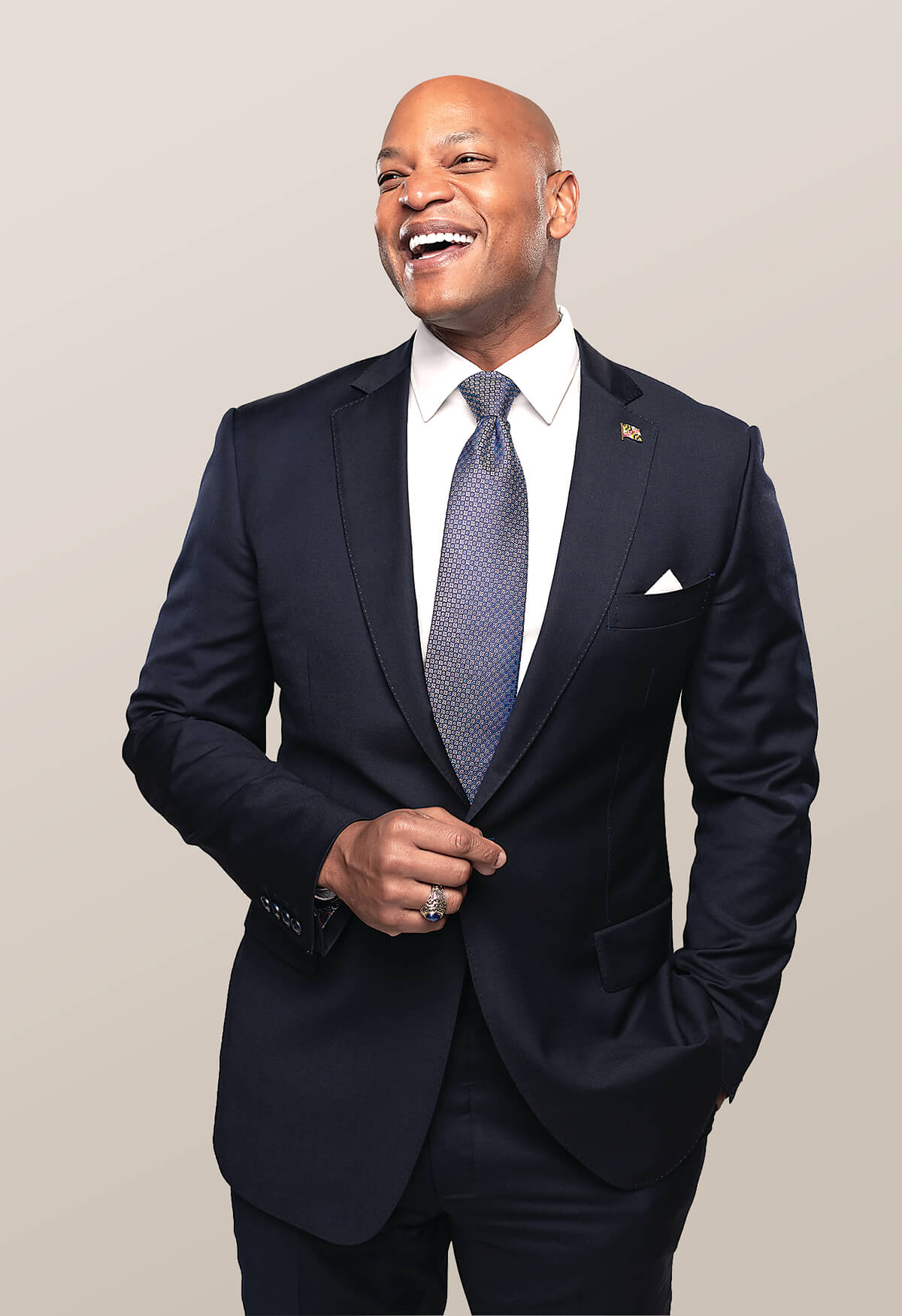

Tall, fit, charismatic, and with the kind of effusive optimism that lights up a room, Moore is an enormously appealing politician in ways far beyond his historic election as Maryland’s first Black governor. He may well have a gained a valuable lesson in the O’s ordeal, which, in the end, drama notwithstanding, was a much-needed 9th-inning win.

At the press conference and official signing, the governor’s normally unrestrained enthusiasm was turned down a self-effacing notch.

“Can I get a second?” Moore asked his Board of Public Works colleagues, formally motioning the lease agreement into the record for a vote.

“Well . . .” chided state Treasurer Dereck Davis.

“Pleaaassse,” Moore responded in faux exasperation, leaning back in his chair and slapping the table as the room burst into laughter. “I can’t take those kind of jokes right now.”

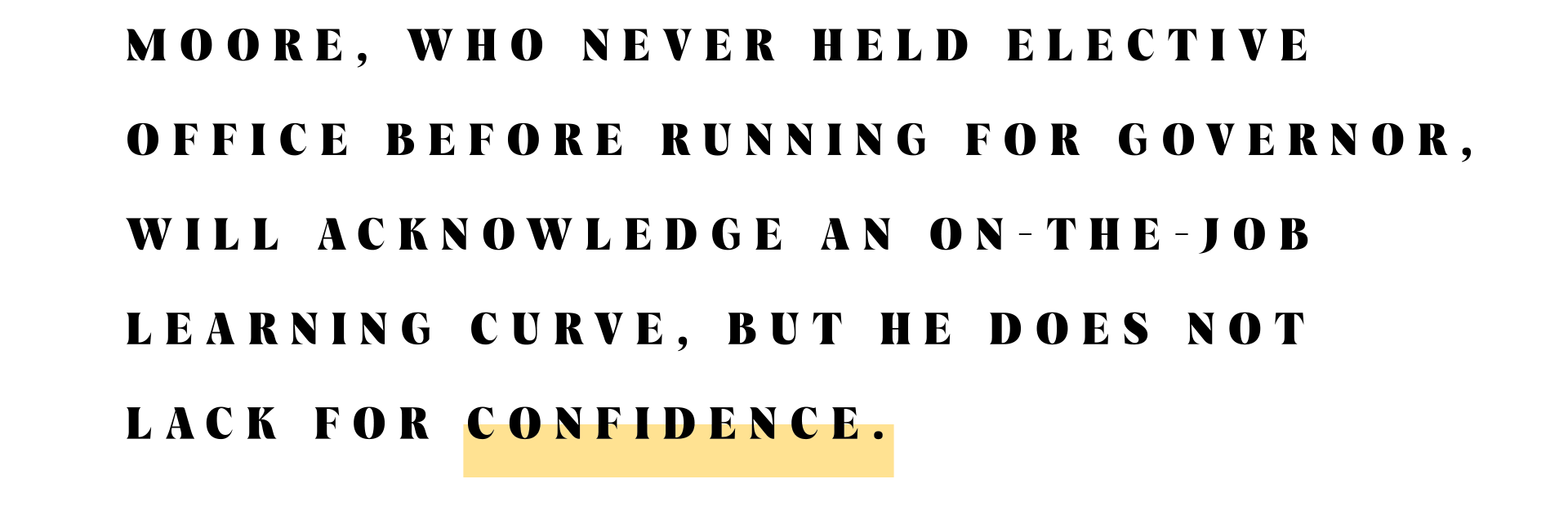

Afterward, as the media gaggle wrapped up, a reporter shouted one last question: “Where do you plan to celebrate?” “Pickles,” Moore said, name-checking the popular Camden Yards sports bar without skipping a beat. He didn’t actually wink as he turned and exited, but he might as well have. Moore, who never held elected office before running for governor, will acknowledge an on-the-job learning curve, but he does not lack for confidence.

The challenges heading into the current General Assembly, however, are much larger and more complicated than the development rights around Camden Yards. The pressing question of the moment goes something like this: Can the 45-year-old governor fulfill his promise and ambitious agenda against massive, looming budget deficits, which threaten to derail everything from basic governmental operations to educational funding and bus, Metro, and light rail service?

Navigating the O’s lease will look like a walk in the park by comparison.

ot only the state’s first Black governor, but the third Black governor ever elected in the U.S., Moore’s journey to Annapolis is literally the stuff of Oprah’s Book Club selections. Published in 2010, Moore’s memoir, The Other Wes Moore: One Name, Two Fates, juxtaposed his own life story against that of an incarcerated Baltimore man of a similar age. Years before, while studying abroad during his final year at Johns Hopkins University, he learned from his mother, then working at the Abell Foundation, that police were seeking someone with the same name—and placing wanted posters in the off-campus neighborhood where her son lived—for the slaying of a jewelry store security guard.

Curious about the incarcerated young man and the different paths their lives had taken, Moore would learn through prison visits that they shared more than just the same name and city. Neither had really known their father. At three, Moore lost his father, a D.C. television journalist, to a rare and misdiagnosed disease. The other Wes Moore’s father was never involved in his life, and he followed an older brother into drug dealing. Moore’s visits to his incarcerated namesake ultimately resulted in the best-selling book, but they also gave him some perspective on his own upbringing. “Even the worst decisions we make don't necessarily remove us from the circle of humanity,” Moore would write.

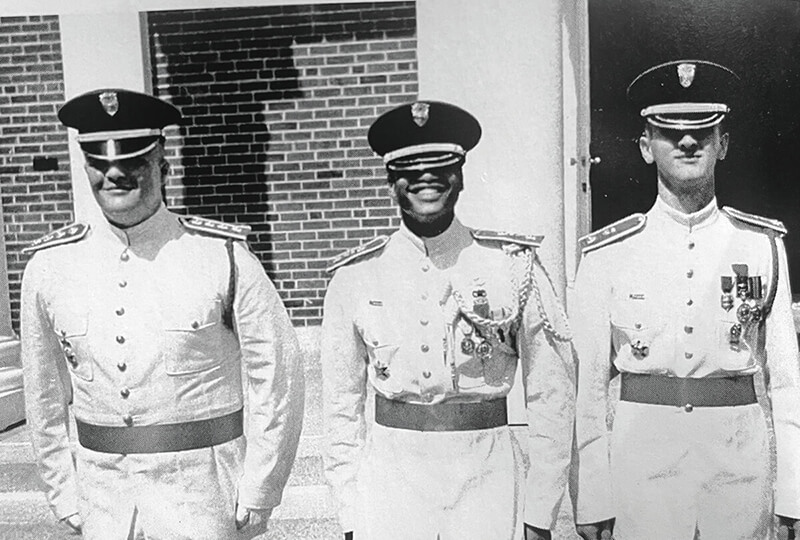

Ater his father died, his mother moved Moore and his two sisters from the D.C. suburb of Takoma Park to the Bronx, where her Jamaican immigrant parents lived. When he started getting into minor trouble in middle school, she shipped him to Valley Forge Military Academy before he ventured further off course. After initial “escape” attempts, Moore soon found role models in the older cadets and a sense of purpose from the male instructors. He embraced the experience so fully that he stayed to earn his associate degree and complete the U.S. Army Reserve’s early commissioning requirements.

The gregarious hugs and contagious energy are evident in the photos from college and even Valley Forge, where he became, not surprising in hindsight, captain of the basketball team, president of his class, and state American Legion oratory champion. (He was such a self-assured teenager that at the 1996 NBA draft, renowned New York Times sportswriter William Rhoden met the then-17-year-old point guard, attending as a fan, and wrote a column about him. The story chronicled the high school senior’s academic dedication and, yes, aspirations for elected office.)

The 100-watt smile and preternatural optimism were passed down separately, he says, through the maternal grandparents who helped raise him.

“People always say I look like my grandmother,” Moore says, gesturing to a photograph behind his desk in the State House, taken as she was filling out her mail-in ballot before his victory. “She died five days before the election. She was a lioness. She was the protective one. The natural optimism, however, that was my definitely my grandfather,” Moore continues. “I don’t want to call it blind optimism, but if there is anyone who should’ve been defeated and broken by the system, it’s him.”

INTERNING WITH MAYOR KURT SCHMOKE. COURTESY OF WES MOORE

Among his grandfather’s childhood memories were the Ku Klux Klan chasing his family from South Carolina back to Jamaica. After marrying, Moore’s grandparents returned to the U.S. His grandfather became the first Black minister in the Dutch Reformed Church and a community leader in the Bronx. They took out a second mortgage so Moore could attend Valley Forge.

“One of the things I just love about him so much is—and, you know, he had this deep Jamaican accent—is that he was maybe the most patriotic American I’ve ever met,” Moore says. “He loved this country. No one was happier when I joined the Army. My belief that things can be better, that we can make them better—that comes from him.”

As fate would have it, Moore interned in the office of Mayor Kurt Schmoke, Baltimore’s first Black elected mayor, while at Hopkins. Just prior to his inauguration, Moore told CBS News that the internship provided a first glimpse into public service and the role government and policy plays in everyday life. “Had it not been for that interaction with Mayor Schmoke,” Moore says, “I know my life would’ve been very, very different.”

Following Schmoke’s suggestion, Moore applied for and earned a Rhodes Scholarship to the University of Oxford as the former Yale scholar had done decades earlier. “I wouldn't say I feel like a proud papa,” Schmoke says. “How about a proud uncle?”

MOORE (CENTER) AS A CADET AT VALLEY FORGE. COURTESY OF WES MOORE

After finishing his studies, Moore returned to the Army and saw combat duty in Afghanistan with the 82nd Airborne Division, earning a promotion to captain. Later, he was named a White House Fellow to Secretary of State Condoleezza Rice. Even before his best-selling memoir, Moore’s résumé and uncommon communication skills were recognized as political commodities with crossover potential. Two years after serving in the White House, he was invited to address the Democratic National Convention, where the then-29-year-old veteran gave a rousing endorsement of candidate Barack Obama “to be my next Commander-in-Chief.”

To Rev. Alvin Hathaway, who grew up with former U.S. Rep. Elijah Cummings and is the retired pastor at historic Union Baptist Church in West Baltimore, Moore stands out as a throwback in this contentious, ego-driven political era, appealing to a purpose greater than oneself.

“I think he has the same kind of charismatic spirit of a John F. Kennedy or a Barack Obama,” says Hathaway, who is overseeing the renovation of Thurgood Marshall’s elementary school and is a friend of Moore’s. “They have a vision and they’re able to build relationships and attract brilliant people to work with them who also have an altruistic bent.

“It’s not the same scale, but Kennedy, who also served in the military, started the Peace Corps. Wes came up with the Maryland year-of-service option. For me, and other old-timers, we can see some parallels.”

But after his military and White House experience, Moore still had résumé boxes to check. He spent 2007 to 2012 on Wall Street before launching BridgeEdU, an organization that provided support to college students. Immediately prior to his gubernatorial bid, he headed the anti-poverty Robin Hood Foundation and served on the board of Under Armour. Since his election, Moore has ascended to national rising star status. A frequent Morning Joe guest—he appeared on the show the day of the photo shoot for this story to tout the O’s lease—Moore is already considered a potential 2028 Democratic presidential nominee.

“He’s a politician cast in the Obama mode, and not just because he’s African American,” MSNBC host Joy Reid told Vogue in a profile of Moore last year. “It’s because of his style of politics—a very aspirational, sort of affirming style, which is almost archaic in our hyper-partisan moment.”

MOORE AT

HIS INAUGURATION,

JAN. 18, 2023. AP IMAGES

worn into office in a moving ceremony on Jan. 18, 2023, which included a wreath-laying trip to the Annapolis city docks where enslaved Africans were once brought ashore, Moore vowed to rebuild state government, speed the transition to clean energy, bridge the equity and wealth gaps, and end childhood poverty. He promised to be bold and declared to Maryland that “our time is now.”

By all accounts, he got off to a remarkable start. The General Assembly passed all 10 of the bills his administration put forth last year, including legislation to raise the minimum wage, expand the Earned Income and Child Tax Credit, and create the first service-year option for young adults in the country. He released money to expand abortion access and signed an executive order protecting gender-affirming care. Not exactly minor items. And he mixed his progressive agenda with a dash of tech seed money and patriotism—testifying himself before legislators on behalf of a retirement tax break for veterans. It’s no wonder his first year was so successful. After eight years dealing with a Republican governor, Democratic legislators, who hold super majorities in the House and Senate, couldn’t wait to welcome one of their own into the Governor’s Mansion.

WITH LT. GOV.-ELECT ARUNA MILLER AT THE WREATH-LAYING CEREMONY IN ANNAPOLIS GETTY IMAGES

Further, Moore scored a major coup this fall when Maryland, specifically Prince George’s County, bested Virginia in the Hunger Games-worthy contest to determine which state should be home to the new FBI headquarters. The state’s Congressional delegation, Prince George’s County Executive Angela Alsobrooks, and former Gov. Hogan all claimed some credit, but it will break ground on Moore’s watch. Up for grabs? Nothing less than 7,500 new jobs and $4 billion in economic activity for a state whose GDP flatlined over the past five years.

All told, an impressive haul. But now, it’s time to wrap up all the good things in 2023 and put a bow on it. Through no fault of his own, Moore is essentially starting over in the General Assembly against suddenly stiff, worse than first projected, headwinds.

Over the next five years, the state’s revenues are expected to grow 3.3 percent annually. The flip side is the additional revenue is outpaced by projected 5.1 percent annual spending increases. Much of the spending demands are driven by landmark school funding legislation passed in 2021, which calls for $3.8 billion in additional annual funding over the next decade. Moore and the Democratic leadership in Annapolis have so far indicated they intend to keep The Blueprint for Maryland’s Future in place, despite pleas from various county leaders that the legislation will break their budgets as well.

Meanwhile, the Moore Administration is lagging far behind its goal to fill at least half of the roughly 10,000 vacancies at state agencies, and the increasing budget deficits won’t help. Unprecedented federal COVID relief dollars papered over deficits in recent budgets, but no longer.

The operating budget is projected to produce a $761-million deficit, which is just the tip of the iceberg. By 2029—potentially, the middle of Moore’s second term—that annual shortfall is projected to reach a whopping $2.7 billion.

An entirely separate pool, the transportation budget projects to a $3.15-billion shortfall over the next six years. That deficit imperils everything from basic road maintenance and regular Maryland Transit Administration bus service to Moore’s proposed revival of the Baltimore Red Line, which his predecessor infamously axed, sending nearly $1 billion of allocated funds back to the federal government.

Speaking of promises, Moore has never committed to reviving the canceled Red Line as a much-needed, east-west light rail system, nor would he commit to do so for this story, only resolving to recreate a “Red Line” of some sort, which, given budget constraints, seems destined to become a scaled-down rapid bus system. In fact, a dozen new highway projects have been put on hold, as well as the proposed expansion of the MARC train Brunswick Line. MTA commuter bus service, which connects suburban Marylanders to jobs in Baltimore and D.C., has been eliminated entirely. As for a third span of the Chesapeake Bay Bridge, former Gov. Hogan’s pet initiative? Don’t hold your breath.

Moore did not cause the state’s structural deficits, of course, but it largely falls on his shoulders to resolve them. (State legislators cannot redirect budget funds but can add to budgets.) By statute, Maryland, like all states, must balance its revenue and spending each year. It’s a trick that will go beyond sleight-of-hand accounting or borrowing from the state’s Rainy Day Fund after this year.

In a December 7 speech to the Maryland Association of Counties days after his Administration released its six-year transportation plan, which calls for eight-percent across-the-board budget cuts, Moore tempered the huge expectations that accompanied him to Annapolis, asking for trust and patience. He’d already heard from most of the county leaders in the room.

“I do know in this moment . . . trust can be tested,” Moore said. “I do know that our ability to invest was constrained by one simple truth, that Maryland is facing significant structural shortfalls.” In the current environment, “we have a duty to act with discipline.”

The reality, Moore admitted, “is I don’t have all the answers, and I’m honest about that.”

The speech covered a lot of positive ground as well, including Baltimore’s record drop in homicides, and Moore received a standing ovation afterward. Suffice to say, the eight-percent transportation cuts were not greeted with the same level of acceptance by Baltimore transit advocates and the General Assembly’s Maryland Transit Caucus, which fired off a public letter in protest. On cue, the day after Moore’s speech defending the cuts, a Baltimore-area light rail car caught on fire and service was suspended for two weeks.

The operating budget revenue crisis stems from lower-than-expected post-COVID sales tax revenues on top of the evaporation of federal pandemic monies. But the transportation outlook is worse. Inflationary construction costs related to the Purple Line connecting Montgomery and Prince George’s counties, the Washington Metro system, and the Howard Street tunnel are one major problem. The other issue is a declining revenue stream, i.e. the gas tax. Hybrid and electric cars are better for the environment, but reduced gasoline use has an unfortunate consequence in Maryland—less state transportation money.

Baltimore Delegate Robbyn Lewis, who founded the Red Line PAC in 2011 to raise support for that project, and Transit Caucus legislators have met with state officials to discuss the cuts. She says that Moore, Secretary of Transportation Paul Wiedefeld, and MTA chief Holly Arnold “get it”—that the proposed cuts hurt communities already underserved by public transit—but apparently, they saw little recourse.

“Welcome to the United States,” Lewis says. “We’ve been letting our infrastructure deteriorate for generations. Anger over the cuts is good. Anger means people are engaged, paying attention, and demanding what they need.” Transportation, she says, is the lynchpin to closing the wealth and equity gaps, which Moore says are his goals.

“You can’t close the wealth gap if you can’t get people to school and work,” Lewis adds. “And let’s talk about equity. Our transportation and transit systems were built to deny Black people access [to certain neighborhoods, jobs, and schools]. When you fix transit, you’re literally dismantling white supremacy.”

At the same time, she says, while Moore is the face of the budget and transportation challenges, it’s incumbent on the legislature to do their part. “What’s the adage, the governor proposes and legislature disposes?” says Lewis. “I knew we were going to hear some ugly news. My questions have been, what can we do to fix it? What’s our strategy? I believe there’s political will to tackle the transportation budget. In the House of Delegates, it’s time to roll up the sleeves.”

Lewis has floated the idea of establishing a half-cent sales tax increase to fund the state’s needed transportation investments, noting that according to the American Public Transportation Association, voters passed 29 of 36 similar funding measures across the country last year.

Delegate Stephanie Smith, chair of Baltimore’s House delegation, also believes that Moore understands the critical nature of public transportation, but similarly struggles to align his stated support for Baltimore with the cuts. “I can assure you,” she says of his transportation plan, “I was alarmed.

“There needs to be more sensitivity to what this means for folks who are going to jobs that cannot be executed remotely,” Smith says, “not to mention children, who are dependent on local transit to get to school in ways that are not relevant in other parts of the state.”

Moore said in his interview for this story that a new funding mechanism to replace the increasingly insufficient gas tax is a necessity. Whether he will support higher tolls or a tax dedicated to rebuilding the state’s transportation infrastructure seems unlikely. After the uproar over the transportation cuts, Moore subsequently restored $150 million of his initial $3.3 billion cuts to the state transportation budget, notably reversing some of the pain particular to Baltimore with a one-off addition of funds.

“Gov. Moore is a student of history and he’s well aware of recent history,” says Len Foxwell, ex-chief of staff to former state Comptroller Peter Franchot and a Democratic strategist, noting the political price of former Gov. Martin O’Malley’s tax increases to deal with Great Recession deficits. “I think he’s going to do everything humanly possible to avoid raising taxes on consumers that are already anxious about their household financial fortunes.

“Governors are ultimately more resistant to tax increases than our individual legislators because most legislators exist in single- party districts that are overwhelmingly Democratic and have relatively little to fear in terms of voter backlash,” Foxwell continues. “It’s also something that could be used against Moore down the road if he pursues what will presumably be his national political aspirations,” Foxwell says. “He’ll have to campaign in states that are not as progressive as Maryland.”

Foxwell adds one more cautionary tale, albeit one that’s genuinely historic at this point: After major highway projects were deferred during World War II, Gov. William Preston Lane Jr. enacted Maryland’s first state sales tax to boost transportation infrastructure funding. It got the Bay Bridge built, which bears his name, but also got him voted out of office.

MOORE IN

HIS OFFICE DISCUSSING

POLITICS.

iven Moore’s early wins, growing national profile, and approval numbers, already among the highest in the country for a governor, it’s easy to forget that he squeaked out a victory in the closest Democratic gubernatorial primary in Maryland since the embarrassing victory of anti-civil rights candidate George Mahoney in 1966. Despite his successes in other fields and immense gifts as a campaigner, Moore began his bid without a great deal of name recognition against a deep field. Ultimately, he edged former Secretary of Labor Tom Perez, 32.4 percent to 30.1 percent. Moore caught a critical break when former Prince George’s County Executive Rushern Baker, running fourth, ran out of money and withdrew six weeks before the primary, throwing a healthy amount of support to Moore.

Oprah’s endorsement and his own fundraising chops also certainly helped him overcome the odds. But Moore also bolstered his case as a change agent with the running-mate selection of former Delegate Aruna Miller, who became the first South-Asian immigrant and woman of color to serve in statewide elected office. (In a watershed election, Maryland also elected Brooke Lierman, the first woman to hold the State Comptroller’s job, and Anthony Brown, the first African-American state Attorney General.)

This fall, a Gonzales Poll put Moore’s approval rating at 60 percent, more than double his disapproval figure. Almost 80 percent of Democrats approve of Moore, while 30 percent of Republicans do, too, likely reflecting his military background and commitment to veterans, which provides an opening to many conservative and older voters. It doesn’t hurt Moore, the father of two school-age children, that first lady Dawn Flythe Moore has had a long career in state politics and is an excellent surrogate.

The numbers are interesting in that they are comparable to Gov. Hogan’s oft-touted approval ratings, even though the two men share few policy positions.

“I’ll say it this way, there’s not just one mold of politician that the public likes,” says Mileah Kromer, a Goucher College political science professor and author of Blue-State Republican: How Larry Hogan Won Where Republicans Lose and Lessons for a Future GOP. “Hogan, who came across as a sort of ‘everyman,’ and Wes Moore enjoy the backslapping and the handshaking to the same degree. They have similar extroverted demeanors, although expressed in very different packages.”

Also, like Hogan, Moore is not known as a policy wonk. He does, however, generally get high marks from fellow elected officials for his managerial, delegation, and relationship-building skills, and for his high-level appointments. As anyone who pays attention to his social media knows, Moore also embraces the cheerleader-in-chief role. He is not shy about wading into the Splash Zone at Camden Yards, taking his shirt off for the Special Olympics’ Polar Bear Plunge, or posing as Frederick Douglass for Halloween.

Along with “extroverted,” “charismatic” is the short-hand description that most often gets applied to Moore. Not a single quality, charisma actually encompasses several traits, requiring different abilities in different settings. Many people possess personal warmth, for example—extending a natural empathy when they meet someone for the first time. Others exude confidence. Still others have a quality sometimes referred to as “presence,” which seems mysterious, but is about residing in the present moment and paying attention to others and their verbal and non-verbal cues. Moore is the rare politician who possesses all these abilities, which is why people are drawn to him. And why, when he talks about the message he’s placed on Maryland’s welcome signs—“Leave No One Behind”—transposing the U.S. Marine’s ethos “Leave No Man Behind” onto society as a whole—many cast him onto the national stage.

Kromer recalls a high-profile political event two summers ago, where she was one of the featured guests with Moore. “The staff of the restaurant was there, just getting ready for work, and I remember watching Wes come in,” Kromer says. “The very first people he spoke with were the staff, and they were very excited. This is the Democratic nominee for governor, the future governor, and apparently, they’re who he wants to talk to. I thought it was revealing. Sometimes the most important person in the room is the everyday voter, and I see him forefront those people a lot.

“You can scoff at that poll question, ‘Does he care about people like me?,’ but there’s a reason pollsters ask that question and it’s about trying to get to the essence of how people feel about a candidate or politician,” Kromer continues. “Especially in a governor, people want to feel like the person in charge cares about people like them.” Meanwhile, The Other Wes Moore remains an interesting read for understanding the foundations of the Wes Moore’s political values.

Moore says he still doesn’t know if he would’ve pulled his life together without military school. What he says he learned in getting to know the other Wes Moore is “how little separates each of us from another life altogether.” He says it made him think deeply about the way privilege and preference work and how kids who don’t have “luck” like he did, will struggle to build lives for themselves.

In conversation in his office, an animated Moore, seated around a coffee table with his jacket off, highlights the role that government has historically played in un-leveling the playing field. He mentions that Baltimore was the first jurisdiction to legalize real estate redlining, creating de facto segregated neighborhoods that survive to this day—and suffer from unfair appraisal values as well. On the federal level, he notes, for example, Black veterans were excluded from the G.I. Bill’s full benefits after World War II.

“Government can, and has to, make resources [education, housing, health care, livable wages] more widely available, so opportunity is not just left to chance or to your ZIP code,” Moore says. “Because government has been very intentional about taking them away.”

When he was running Robin Hood, Moore would often talk about the role of government with people and hear the recurring refrain: “People in poverty, they just need to work harder," he recalls. “And I remember challenging people and saying, ‘Why do you think poverty exists?’ I’d say, that’s not a rhetorical question. I’m really asking, ‘Why do you think poverty exists?’”

To him, poverty has been intentional. “We’ve intentionally decided who wins. We’ve intentionally decided who gets access to opportunities and who doesn’t,” he says. “We’ve chosen that we were going to be a society of winners and losers, and the thing that I don’t agree with is, that sometimes you hear people say is, ‘That’s just the way capitalism works.’ No, that’s the way a corrupted form of capitalism works.”

Moore says he doesn’t believe in “quote unquote” redistribution of wealth, but in creating systems that give people the opportunity to succeed. “I’m not asking that everyone ends up in the same spot, but I am saying everyone should have a fair shot.”

A YOUNG WES WITH HIS GRANDFATHER. COURTESY OF WES MOORE

Moore reflects on his immigrant family’s story again. “My grandfather, who had a remarkable life story, devoted his life to this country, devoted his life to the ministry, to his community, and to his family and made tremendous impacts all throughout his life,” Moore says. “And he’s a person, who, when he passed away, had nothing to pass down to his children. Is that fair? No, it’s not. And that’s the point, because no one can argue that it’s because he didn’t work hard enough.”

Earlier in the morning, inside the large ceremonial room in the State House down the hall from his office, Moore had mentioned the unveiling of Gov. O’Malley’s official portrait over the summer. Traditionally, portraits are unveiled either shortly before a governor leaves office or shortly after a new governor is sworn in.

O’Malley, as Moore recounted, preferred to wait until after Gov. Hogan was out of office for his unveiling. (Hogan constantly attacked O’Malley in his bid to beat his hand-picked successor, Anthony Brown.)

The plan was that O’Malley’s portrait would eventually replace that of disgraced former Gov. Spiro Agnew. Agnew’s legacy, as we know, is that he was forced to resign the vice presidency over a corruption scandal. By coincidence, the portrait of Gov. Marvin Mandel—who had to step aside during a corruption scandal—currently stands next to Agnew’s.

The portraits of recent governors Blair Lee, Harry Hughes, William Donald Schaefer, Parris Glendening, Robert Ehrlich, and Hogan—all white men, of course—hang across the room.

Paintings of Leonard Calvert, the first colonial governor of Maryland, and his brother Cecil Calvert, the second Lord Baltimore, and Proprietor of Maryland from 1632-1675, hang side by side on a third wall. Moore is well aware of Maryland’s founding family’s shameful record on race. Under Cecil Calvert, Maryland became the second colony, after Virginia, to define slavery as hereditary by law.

When asked, while looking at the visages of his predecessors, what he hoped his legacy would be, Moore once again did not skip a beat. “That we didn’t miss the opportunity of this moment.”