History & Politics

After the Fire

In February 1904, downtown Baltimore was utterly destroyed by a ravenous fire that burned for two days. Just two years later, a new city—the one we live and work in today—had risen from the ashes. We look back at the rebirth of a great American city, and hear the echoes of the present in the voices of the past.

[Editor’s Note: 2/7/2024: This 2004 piece by then-contributing writer Jim Duffy ran in our February issue 20 years ago this month. We re-share it today in commemoration of the 120th anniversary of the Great Baltimore Fire—a “blaze for the ages” that obliterated 86 city blocks, consumed 1,526 buildings, and killed five Baltimoreans.]

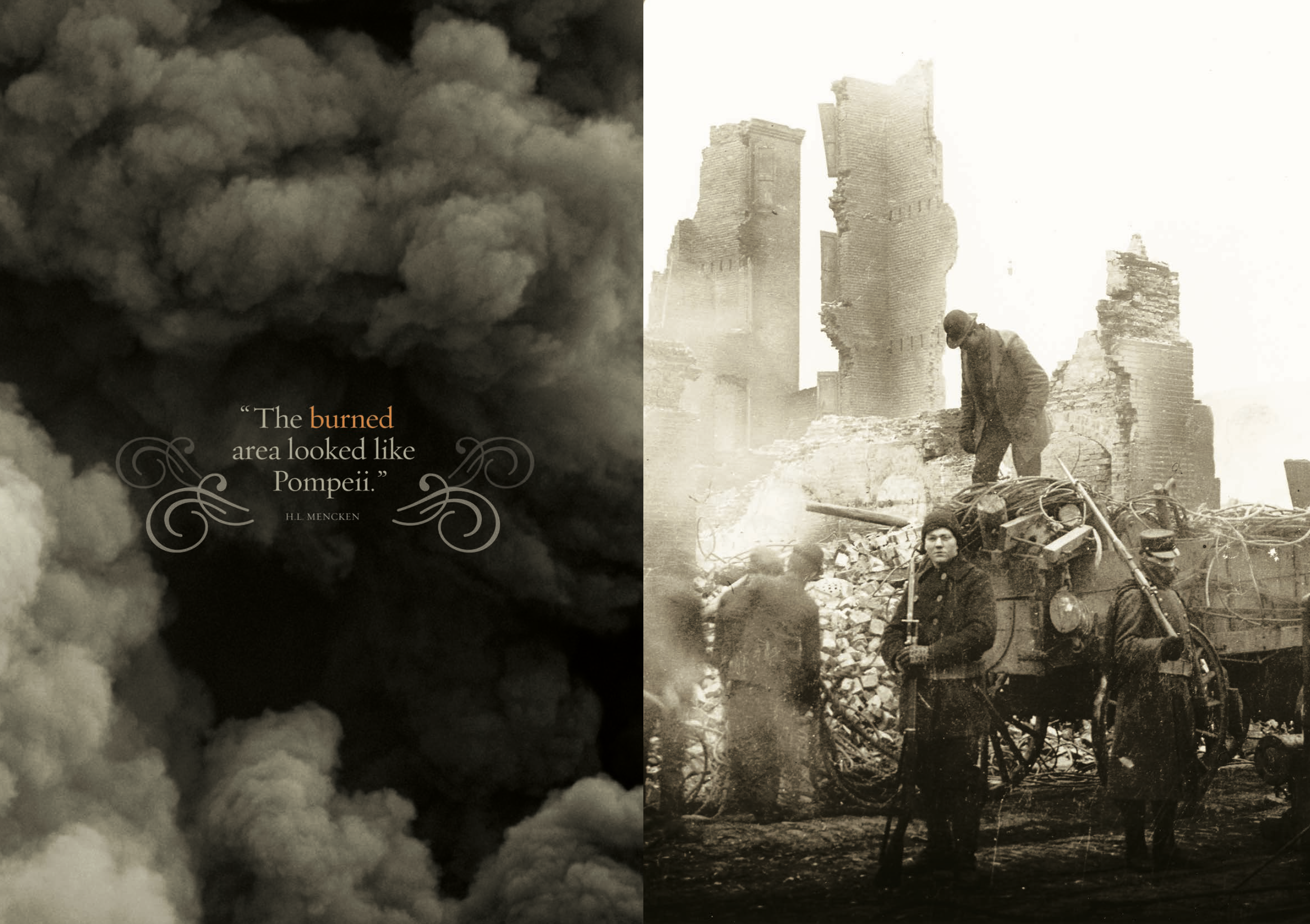

It’s hard to believe that H.L. Mencken could sum the scene up in six words, but there you have it: “The burned area looked like Pompeii.”

Strange, isn’t it, how hard it is to find your bearings in the vast, frozen rubble? What corner is that? Which way is the camera pointed? Wait…yes…there’s the City Hall dome!

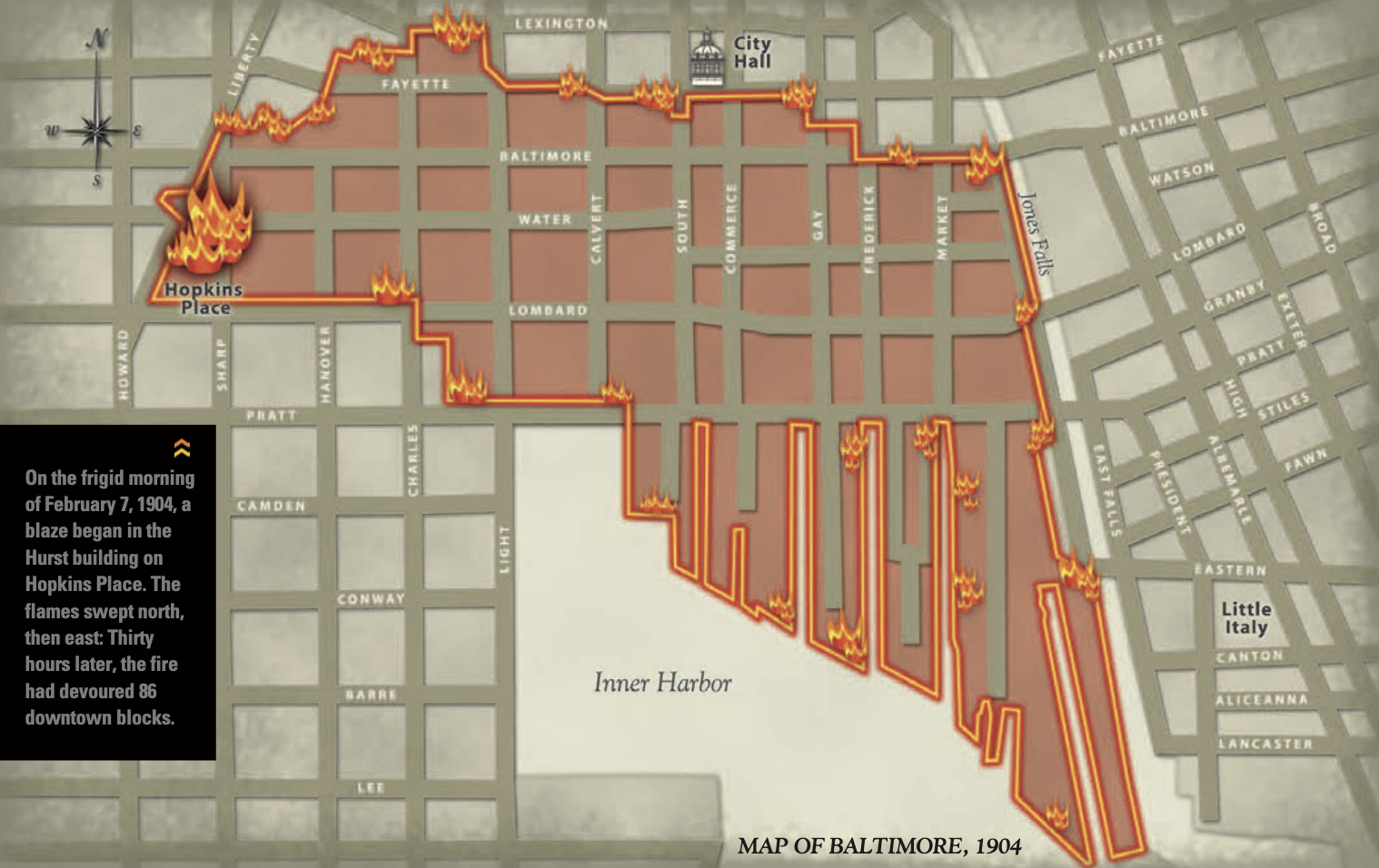

A century ago this month, Downtown Baltimore went up in flames. No one knows how the blaze started, though all the experts seem content enough with a piece of pure conjecture about a carelessly flicked cigar passing through a window into the basement of the Hurst building that stood on Hopkins Place, where the Baltimore Arena is today.

Historians are on firmer ground when they rank the resulting conflagration as a city-defining moment, one on a par with the defense of Fort McHenry in 1814, and the 1833 founding of the B&O Railroad. The fire raged for two days, February 7 and 8, a Sunday and a Monday. Stiff, shifting winds pushed the blaze north, then east along a clockwise arc and kept firefighters constantly on their heels.

The Baltimore Sun, Feb. 8, 1904: “There is little doubt that many men, formerly prosperous, will be ruined by the events of the past 24 hours…Many of the spectators saw it all go up in flames before their eyes, and there were men with hopeless faces and despairing expressions seen on every hand. In fact, the throng seemed stunned with the magnitude of the disaster and scarcely seemed to recognize the extent of it.”

It’s still hard to fathom the extent of it. On the one hand, only one person died in the blaze (with four more succumbing later to fire-related causes). On the other hand, the fire obliterated 86 city blocks, consuming 1,526 buildings that housed 2,500 businesses. It was, without a doubt, a blaze for the ages: not as big as the legendary 1871 Chicago fire, but a lot bigger than the famed 1872 Boston fire.

In the old pictures, a few human figures stand amid the ruins. But they’re distant, recognizable now more as types than as individuals—soot-covered immigrant, stoic businessman, grim civic leader, drained firefighter. This being a city (then and now) flush with coincidental small-town connections, it’s natural to take an elongated look, wondering whether any of those lives brushed up against yours over the generations.

Perhaps that immigrant was one of your great-grandfather’s shot-and-a-beer buddies. Perhaps that firefighter started a family tradition that reaches the fourth-generation firefighter in the rowhouse next door. Perhaps that well-dressed man’s name ended up on your business card—the old newspaper clippings are chock full of Venables, Marburys, and Semmeses.

Eventually, the wandering mind makes its way back to the point: What was it like to watch the city burn?

The Baltimore American, Feb. 8, 1904: The Maryland, a lunch room, “was brilliantly lighted and patronized by men of grime and of worry…[W]hile they dined a stringed orchestra played beautifully. Soon the rain of sparks in the street made the young lady waitresses nervous, but the leader of the band and his men kept on, oblivious to all except the time and the tune. Then the general cry for retreat went up and, seizing the cash register and a few valuables, all rushed to the open air and safety.”

Some people credit divine intervention for staving off an even more monumental catastrophe. Fervent prayers issued from St. Leo’s Church found answer when the blaze failed to jump the Jones Falls and ravage Little Italy. Others speculate about a more devilish force, noting that the fire backed off on the brink of consuming the old Monumental Burlesque House.

The Baltimore American, Feb. 10, 1904: “Yesterday, however, it was but a smoldering mass of ruins, with no element of danger of further spread. This brought a feeling of indescribable relief to everyone, and the representatives of the commercial, financial, and manufacturing life of Baltimore were free to turn their minds to thoughts of the future.”

The Baltimore Sun, Feb. 8, 1904: “There is little doubt that many men, formerly prosperous, will be ruined by the events of the past 24 hours…Many saw their all go up in flames before their eyes…The throng seemed stunned with the magnitude of the disaster.”

There are many fine ways to mark the centennial of an event so seminal to this city. Some will chase the fire’s mysterious origins. Some will mourn lost architectural gems. Some will relish the heroics of firefighters (and their horse-drawn equipment). The exhibits, tours, and lectures planned around town for the months ahead promise something for every interest.

My own interest is focused on what happened after the fire. Perhaps that’s because there are echoes of current events at New York City’s Ground Zero in the story of the rebuilding of Baltimore. Everybody back then was stunned to find that “fireproof” buildings were nothing of the sort. Crews clearing the rubble worried that post-fire dust would be the respiratory death of them. Rebuilding plans and proposed memorials stirred passionate debates.

The rebuilding story also speaks to current events close to home. A century after the fire, Baltimore once again finds herself about the hard work of raising a new city. Look at the west side of downtown, where the new Hippodrome opens this month. Look at Inner Harbor East, on its way to becoming a little downtown of its own. Then keep tracking the shore down to Canton Crossing, where things are just getting started. Head up to the East Side, near Johns Hopkins Hospital, where they’ve basically decided to create on purpose the situation faced by city leaders after the Great Fire; they’re reducing the area to rubble and then starting over again with a biotechnology park.

On the morning I write this, there’s a story in the paper about a single property on the west side of downtown that’s been trapped for six years in a purgatory of redevelopment paperwork. Six years! Maybe someday it will win a meaningful approval. Maybe someday after that a shovel will strike ground.

Fanned out across my desk are scores of blurry microfiche printouts of stories detailing Old Baltimore’s response to the fire (we had five major daily newspapers back then). It took just two short years—tumultuous years, to be sure, but two short years nonetheless—to clear her 86-block sea of rubble and raise a completely new downtown.

Not only that: The buildings that burnt had a combined value of $13 million. Their replacements were worth $35 million. The rebuilt downtown had better, wider streets and a better, more productive harbor. It delivered Baltimore into a future much brighter than it would otherwise have found.

How’d they pull that off? Could we modern-day Baltimoreans have done as well? Are we doing our rebuilding jobs as well?

The Baltimore News, Feb. 8, 1904: “To suppose that the spirit of our people will not rise to the occasion is to suppose that our people are not genuine Americans…We shall make the fire of 1904 a landmark not of decline but of progress.”

To be frank, Old Baltimore was in rather desperate need of progress. Downtown streets dated to colonial days. They were narrow, confusing, ill-connected and, as a result, paralyzed by horsedrawn traffic jams. Even pedestrian progress was an iffy proposition, thanks to the mish-mash of utility poles sunk in sidewalks to prop up an ugly, never-ending web of overhead wires.

The city’s wharves and port facilities were all but obsolete. The harbor was so thick with silt that only constant dredging kept its depth at 20 feet. That was deep enough for the old sailing ships, but everyone could see that the future belonged to steamships.

Last but far from least: sanitation. Imagine all the mounds of horse poop on those poorly drained streets. Imagine a city without a proper sewer system, its human waste routed from indoor water closets to stagnant nearby cesspools or into open ditches leading to open streams. The sweepers, shovelers, and scrapers who toiled to clear the muck went by a rather hopeful name: the Odorless Excavators Association. Not even they could prevent the filth from flowing freely on those frequent occasions when the Jones Falls flooded, inundating downtown clear to Calvert Street.

Old Baltimore wasn’t so much oblivious to her problems as impotent in the face of them. Most historians blame a brutal municipal hangover lingering from the Civil War, which created bitter divisions in Baltimore’s population while tearing away at the Southern roots of the city’s cultural and business life.

The “war sapped the vitality of an entire generation,” James B. Crooks writes in “Politics and Progress: The Rise of Urban Progressivism in Baltimore 1895–1911.” “Economically, Baltimoreans became more conservative; politically, they became apathetic; and psychologically, they became less daring.”

Nothing came of sanitation commissions established with great fanfare in 1881 and 1893. At the time of the fire, yet another sewer plan was before the General Assembly. As always, the Odorless Excavators lobbied furiously against it. Other civic-minded initiatives died at the ballot box as cynical voters convinced that official corruption was endemic rejected one bond referendum after another.

Still, some Baltimoreans were trying to revive their tired city. Inspired by the City Beautiful movement, the fledgling Municipal Art Society made lots of noise about better schools, wider streets, and new parks. Under editor Charles Grasty, the Baltimore News had become a powerfully progressive voice. In another hopeful sign, the dashing young Robert McLane was narrowly elected mayor in 1903. (McLane was a few months younger at his inauguration than Martin O’Malley was at his.)

The scenery and the players were now in position. Yet over the ensuing years, historians have gone back and forth on the chicken-or-egg question: Did Baltimore rouse herself just in time for the fire? Or was it the fire itself that finally roused her?

There are moments in the fire story when Old Baltimore seems not a century away, but a millennium. As news of the catastrophe spread across telegraph wires, everyone everywhere wanted to help. There was talk of emergency federal aid. Neighboring states offered money, manpower, and equipment. Spontaneous donations started arriving in the mail at City Hall.

The Baltimore News, Feb. 9, 1904: “Mayor McLane made the following statement to the News this morning: ‘As head of this municipality I cannot help but feel gratified at the sympathy and the offers of practical assistance which have been tendered us…To them I have in general terms replied: Baltimore will take care of its own people the best it can…but we thank you, and we appreciate it just the same.”

Some $60,000 in donations arrived in the mail before McLane’s message got out. All was returned, accompanied by properly polite thank-you-but-no notes. The city did accept $250,000 from the state of Maryland to help the injured and unemployed, but 90 percent of those funds were later returned to the state treasury.

Report of the Citizens’ Relief Committee, 1906: “In view of the enormous losses, the remarkably small showing of only $23,000 disbursed proves that the virility and self-respect of Baltimore’s citizens can not easily be matched, and their spirit of independence and capacity for self-help calls forth, even in this progressive age, wonder and admiration.”

As investigators waded into the rubble after the fire, snippets of encouraging news slowly trickled in. Buildings housing banks may not have been fireproof, but the vaults were, so securities and cash survived. Insurance companies offered public reassurances about their solvency. The predicted riots and looting didn’t materialize. Burned-out businesses scrambled to regroup.

The Baltimore News, Feb. 10, 1904: “RUSH FOR HOUSES. $75,000 Given for Building Worth. $37,000 Sufferers From Conflagration Glad to Pay Any Price For Temporary Quarters. North Charles street is now temporarily the center of the financial district. Almost every building is being offered for sale and some exorbitant prices are being asked.”

Of course there was profiteering: This is Baltimore, after all. What did you expect? But more important was the way some farsighted businessmen sensed straight away that the fire presented an opportunity to tackle the city’s seemingly intractable problems. On Tuesday, Feb. 9, retired railroad executive William Keyser called the first informal meeting of like-minded leaders. A follow-up session the next day included the mayor himself.

The Baltimore American, Feb. 11, 1904: “BALTIMORE BRAVE AND DETERMINED WORLD ADMIRES OUR GRIT…To carry out this civic spirit a meeting was held yesterday at City Hall, and steps will at once be taken to organize a special body that will announce to the world, and then proceed to furnish proof thereof, that Baltimore is fully able to cope with the calamity that has befallen it.”

That Friday, McLane named an advisory Citizens Emergency Committee. Its roster reads like a guide to the grand institutions and legal patriarchs of modern-day Baltimore: Henry Walters, Theodore Marburg, William H. Welch, Richard M. Venable, John E. Semmes, Sherlock Swann, Henry Stockbridge.

The headlines may have been gushingly optimistic, but the newspapers also carried reports hinting that caution remained the watchword for many Baltimoreans. Unnerved by the thought of thousands of men suddenly unemployed and hordes of strangers in town to gawk at the devastation, residents in a glitzy new suburb called Roland Park hired extra security patrols. The Maryland National Guard was called in to patrol downtown. And every tavern in the city was ordered shut down.

The Baltimore American, Feb. 15, 1904: “The efforts of saloonkeepers and breweries to elude the blockade of police and militia has led to the adoption of odd devices. Every kind of vehicle has been pressed into service to carry beer, and a story is current that an enterprising saloonkeeper in the Eastern district secured his beer by sending a hearse for it.”

Unnerved by the thought of thousands of men suddenly unemployed and hordes of strangers gawking at the devastation, residents in a glitzy new suburb called Roland Park hired extra security patrols.

The new advisory committee threw caution to the winds. It split into subcommittees that began issuing reports in as little as three days. Streets should be widened. Parks should be built. Electrical wires should be buried. Wharves should be rebuilt. The harbor should be dredged. A proper sewer system should be built. The committee recommended that the rebuilding be planned and executed through a powerful new entity called the Burnt District Commission (whose acronym, by fitting coincidence, matches that of the modern-day Baltimore Development Corporation). Squeezed by a shortage of space at City Hall, the five-member commission headed by Sherlock Swann held its meetings in a janitor’s closet.

The Baltimore American, Feb. 15, 1904: “FINE PLANS FOR A MODEL CITY. The citizens of Baltimore yesterday, many for the first time, had a chance to pause sufficiently in their work to realize that a new era has been entered—that the Metropolis of the South stands upon the threshold of an epoch full of possibilities for a greater, more progressive and more influential Baltimore, whose importance cannot as yet even be estimated.”

The whole city seemed suddenly drunk with civic good will. Newspapers served up quote after hyperbolic quote from businessmen and politicians. Nary a cynical word was heard, even in the face of recommendations that the new Baltimore should be modeled after Paris—that’s right, the one in France. Then the real work began. And it became all too clear that wider streets meant smaller lots for new buildings, that new parks meant lost lots for some property owners, that rebuilt wharves would have to be city-owned—what of their current owners? At the risk being overly harsh, one might say that everyone in Baltimore favored every proposed improvement except the one that touched on his own holdings (and thus was “Not In My Backyard” born). Soon, voices of dissent were raised. Public rallies in opposition were mounted.

The Baltimore World, Feb. 19, 1904: “Delays are dangerous, and the great danger that hovers above Baltimore today is in delay…Every man who by penuriousness or greed puts a stumbling block in the pathway of the city’s improvements hangs a weight about his own neck, for in retarding the work, and hence the city’s progress, he depreciates his own property. Let us hope that no business man or property owner will fail to measure up to the needs of this occasion, or show that his greed is greater than his love for his city.”

McLane and his allies were nothing if not shrewd. The enabling legislation for the Burnt District Commission (which they had rushed through the General Assembly after the fire) gave the two city council branches that then wielded great power in Baltimore zero authority to amend the plan for new streets.

Pass it whole. Reject it whole. Take it or leave it. Those were the only options. Leave it, and pay the price.

The Baltimore American, March 11, 1904: “Baltimore’s City Council will lay itself open to severe public censure if any of the members allow themselves to get into wrangles over the ordinances required for the rebuilding…There is strong public demand…for prompt action, for no squabbles, for a hearty cooperation in every measure.”

McLane explained the strategy in simple, down-home terms: “We do not want to take three bites at the cherry.”

But his quote is rich with between-the-lines food for thought. His way managed all at once to be populist, progressive, and thoroughly anti-democratic. Sometimes, it seems, serving the public good—even doing the public’s will—requires making an end run around the public’s elected representatives.

Said representatives were none too happy to discover their powerlessness. On March 30, the Second Branch of the City Council erupted into open revolt and cast a stunning preliminary vote to dump the whole rebuilding scheme.

The Baltimore Sun, April 2, 1904: “Act, do something! The spirit of hopefulness and courage with which our citizens faced their calamity the day after the fire is being frittered away while Councilmen, intent upon petty features of the problem, demonstrate their incapacity to comprehend its larger features…The people of Baltimore want the work of rehabilitation to begin right away. They want deeds, not words.”

In the end, they got deeds. But the recalcitrant City Council got something, too—a compromise that killed the most controversial of the proposed widenings, Baltimore Street. The roads that were widened (by anywhere from 15 to 63 feet) include Hanover, Charles, Light, Pratt, St. Paul, Calvert, and German (now Redwood) streets, along with Hopkins Place.

An obvious question still lingers: Where’d the money come from? That brings us to a tale of timely good fortune.

The city had long before sunk some money into the Western Maryland Railroad. But by 1874, when John Mifflin Hood took over a bedraggled WMR, that investment looked like a bad bet, likely to end in a total loss. To everyone’s surprise, Hood turned the railroad around. When he sold WMR in 1902, the city cleared $8.7 million. It was a windfall just sitting there in the city’s coffers when the fire broke out.

The Baltimore World, Feb. 19, 1904: “There’s a good deal of silly sentiment about the Western Maryland money that must disappear in the face of a desperate business proposition such as now confronts us. If the Western Maryland money can help us, we should not hesitate a moment to use it.”

The windfall helped Baltimore get off to a fast start, but it didn’t come close to covering the whole rebuilding bill. Fortunately, a once-cynical public had by now changed its tune: Between 1904 and 1911, Baltimore voters approved bond issues totaling $50 million.

Soon enough, we will move on to our reasonably happy ending ending. But the events of 1904 necessitate a couple of unfortunate detours first.

One is a personal tragedy. On May 30, 1904, Mayor McLane returned home from City Hall, and promised to take his new bride of just a few weeks out for a carriage ride. He went to his room; there was a shot, and he was found dying of a bullet wound to the head, presumably a suicide attempt. The historical record has whispers of domestic troubles and speculations about the pressure of the mayor’s public position. Some even suspected murder. But no plausible explanation was ever offered. McLane served as mayor for just 385 days.

The second detour returns us to larger civic affairs. Though Baltimore seized many important opportunities after the fire, she also missed out on a few. No memorial to the fire ever got built. Parks got squeezed out of the redevelopment plan, including a grand one that would have stretched along the south side of Fayette Street from the east end of City Hall to the west end of the Post Office and perhaps beyond.

Among the many advocates for this plan was Frederick Law Olmsted Jr., the son of the famed landscape architect. The younger Olmsted weighed in on the rebuilding in a report published by the News on Feb. 20, 1904. He suggested an entirely new street slice diagonally downhill from Baltimore and Park to Pratt and Light. Not only would it would ease congestion, he argued, it would also “form a splendid vista” of the harbor. Olmsted saw something in the harbor that few contemporaries did.

One gets the sense that if he were alive today, he would not be surprised in the least by the Inner Harbor. He proposed a pedestrian promenade for the waterfront, lined with plantings and lights. He suggested that scenic overlooks be placed atop the sheds that would sit along the new wharves.

“There is not a more interesting sight among all the activities of a city,” he wrote, “than the coming and going and maneuvering of big vessels and small craft in a busy harbor…My point is that in a comprehensive and intelligent treatment of the waterfront many matters of appearance and recreation can be provided for by the exercise of some thought…[and] without any material addition to the tax-payers’ burden.”

Olmsted wasn’t always so prescient, however. He also told Baltimore not to fret about its trolley lines, because it was inevitable that the city would soon develop a proper subway system.

Frederick Law Olmsted Jr., son of the famed architect, suggested an entirely new street slice diagonally downhill from Baltimore and Park to Pratt and Light. It would “form a splendid vista” of the harbor.

And so Baltimore’s plan wasn’t perfect. But what plan is? In “The Limits of Power: Great Fires and the Process of City Growth,” historian Christine Meisner Rosen compares how well Baltimore, Boston, and Chicago recovered from their respective fires. Her conclusion is blunt: “Baltimoreans achieved more of their improvement goals more fully than the others, and consequently solved more problems.”

One can only imagine the scene downtown as 1904 gave way to 1905. Six months after the fire, 236 buildings were under construction. One year after the fire, more than 200 new buildings were completed and 170 more were under construction. And two tumultuous years after the fire, Baltimore had earned the right to do a little chest-thumping.

The Baltimore Sun, Feb. 7, 1906: “TWO YEARS AFTER FIRE BALTIMORE IS BOOMING. Marvelous Progress In Building, Manufactures, Municipal Improvements And General Business. RARE OPPORTUNITIES FOR CAPITAL. The Loss of $100,000,000 By The Conflagration Has Not Only Been Recovered, But The Aroused Enterprise Of The People Has Gone Something Like $100,000,000 Better—How One Of The Greatest Disasters Of Modern Times Has Been Converted Into A Blessing.”

The following September, the city threw a week-long Baltimore Jubilee. There were speeches and sermons and cheers. There were parades, concerts, light shows, and carnivals. There were tens of thousands of revelers downtown every night for a week.

Ninety percent of the lots in the burned district were occupied by then. The street improvements were finished—those are the streets we drive today. The wharves were being rebuilt—those are the piers of today’s Inner Harbor. The sewer system was in the works—that’s the one that’s still working (barely) today.

All played a critical role as Baltimore made the transition from one economic era to another, from dealing in dry goods to becoming a manufacturing powerhouse. In 1904, Baltimore’s industrial output was pegged at $150 million. By 1927, that climbed to $700 million.

When it comes to numbers like this, the historians argue back and forth about the impact of the fire. Some say the fire sparked a great revival. Others think Old Baltimore would have managed just fine in the new century in any case.

The Baltimore American, Sept. 10, 1906: “The conflagration destroyed all but hope and courage, and the two combined have raised from the ashes a new and greater city…Even the casual visitor [will be] compelled to admit that the Monumental City contains all that is possessed by any other city in the country.”

Not quite the Greatest City in America, perhaps, but at least Baltimore was in the running.

This story is based in part on interviews with Stephen Heaver of the Fire Museum of Maryland, Jeannine Disviscour and Barbara Weeks of The Maryland Historical Society, historian Dr. Pete Petersen of Johns Hopkins University, and historian Wayne Schaumburg, who has taught classes about the fire at several local colleges.

In addition to the newspaper articles, books, and official documents mentioned directly in the text, the most important written sources for the article were Baltimore Afire by Harold A. Williams, Baltimore on the Chesapeake by Hamilton Owens, Newspaper Days by H.L. Mencken, and “History of Baltimore 1870–1912,” an essay by John M. Powell in the book Baltimore: Its History and Its People.