History & Politics

Preserved H.L. Mencken House is a Palpable Step Back in Time

Union Square home of the prolific journalist reopens after 23 years.

“I have lived in one house in Baltimore for nearly 45 years. It has changed in that time, as I have—but somehow, it still remains the same… It is as much a part of me as my two hands. If I had to leave it, I’d be as certainly crippled as if I lost a leg.” —H.L. Mencken

The sofa arrived on a dreary, wet evening this past winter after residing in the Annapolis office of former Maryland Senate Majority Leader Mike Miller for the past decade. The rain and damp weather didn’t diminish Brigitte Fessenden’s enthusiasm one bit.

“It was wrapped in a plastic cover and carried in by two women,” says Fessenden, president of the Society to Preserve H.L. Mencken’s Legacy, with a smile. “I think Mencken would’ve enjoyed watching that while he smoked his cigar.”

Shuttered for 23 years and recently reopened pre-quarantine, the longtime home of the journalist, essayist, and cultural critic known as the Sage of Baltimore faces Union Square in southwest Baltimore. In fact, the prolific Mencken, author of such works as Happy Days, Notes on Democracy, and The American Language, did much of his entertaining in the sitting room, where the sofa offered respite to F. Scott Fitzgerald, among others.

“It’s one more piece of the puzzle,” says Fessenden, who has spent much of the past year meticulously researching, recollecting, and reinstalling Mencken’s original chairs, lamps, carpeting, bookshelves, piano, and paintings and placing everything back where it was when the former Baltimore Sun newsman lived in the three-story rowhome.

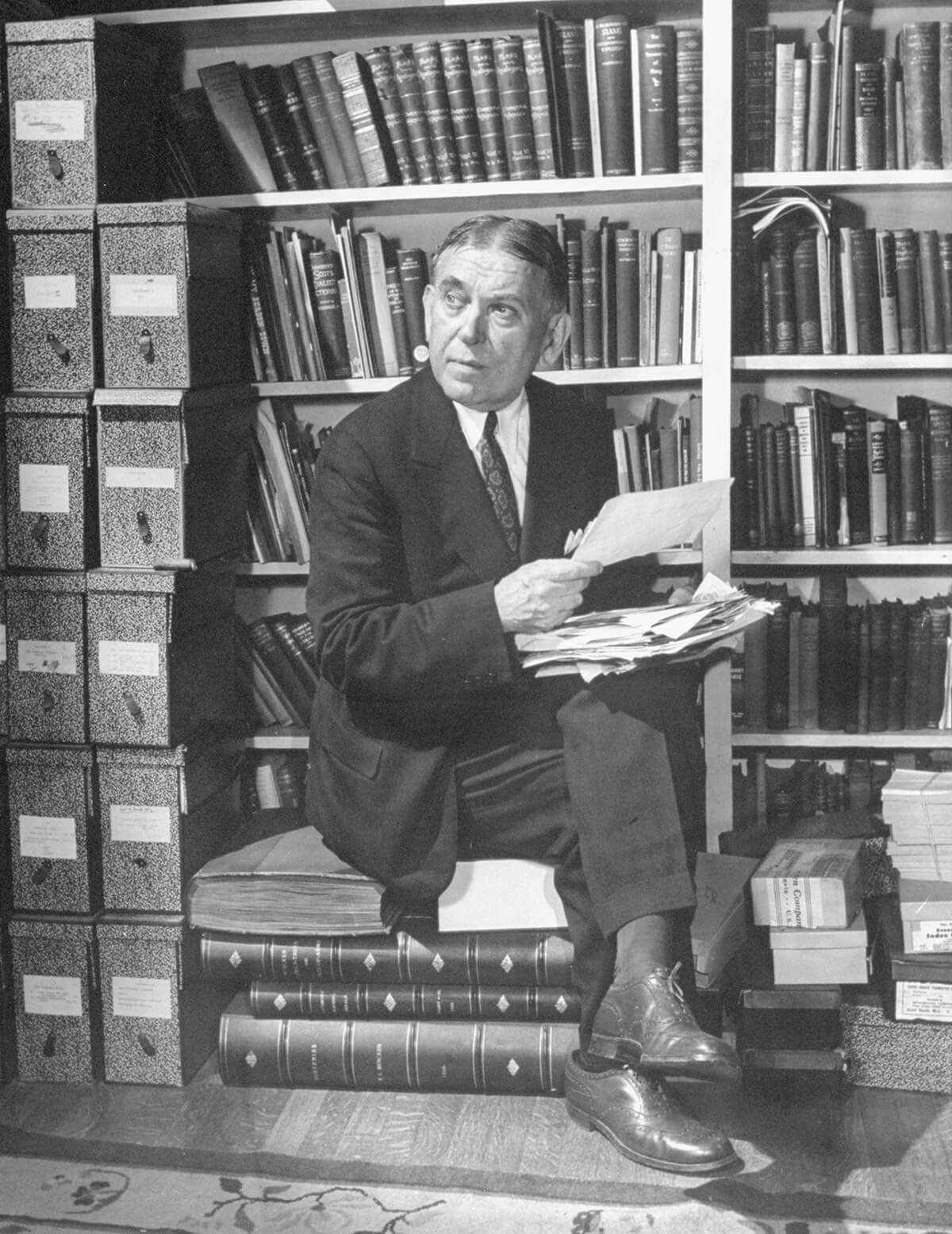

The attention to his study alone, a palpable step back in time, is striking. (It was here where Mencken’s “councils of war” plotted strategy against various government book-banning efforts and where Mencken persuaded Clarence Darrow to defend John Scopes in the Scopes Monkey Trial.) Mencken’s own lightweight, early 1900s L.C. Smith & Bros. typewriter, for example, has been restored to remarkable condition—evocative of a refurbished Stradivarius—with functioning type bars, spool, roller knob, and keys.

Nearby sits his favorite brand of thin replacement leads for his pencils, his sharpener, his memo pads—produced by the “Universal Atlas Cement Co.”—a box of Pilot brand staples, a bottle of Sheaffer Skrip ink, and five-cent mailing labels. His wooden chair is solid, upright, and worn—like those of all serious writers.

After the unexpected 1997 closure of Baltimore’s City Life Museums, which previously operated the Mencken House, the three-story brick home basically sat vacant. For the most part, the home’s belongings have been kept in storage by the Maryland Historical Society. Since his death in 1956, Mencken artifacts have scattered far and wide, including to the Enoch Pratt Free Library’s H.L. Mencken Room, private collectors, and the Smithsonian. Fessenden only recently discovered Mencken’s famous red suspenders in a wrongly marked box. “That made me happy,” she says with another smile.

That it took the city more than a dozen years to disperse a private $3-million bequest to fix the place up would not have surprised the acerbic Mencken. “Every decent man is ashamed of the government he lives under,” he once said.

Mencken’s legacy, of course, is complicated. There is no denying his stature as one of this country’s original thinkers. There is also no question he displayed anti-Semitism and used the racist pejoratives of the time. But Mencken also published black writers as founder of the groundbreaking American Mercury magazine. At the moment, there is the hope that the restoration and reopening of his home will not just attract visitors there, but will spark renewed interest in his work.

Going forward, there is additional hope the Mencken House can serve as a foundation for continued neighborhood development around the graceful, 2.5-acre city park at its doorstep. There’s even aspirations Mencken can become a Baltimore institution in the way the Edgar Allan Poe, whose home, of course, is a popular destination, has become inseparable from the city’s identity. But obstacles remain.

“Not all geniuses are movie-star good-looking,” says Jeff Jerome, former curator of the Poe House and now outreach coordinator with Mencken House, referring to the challenges of promoting the image of the portly, middleaged, sometimes dour, and often sarcastic writer. “At least Poe was weird-looking.”