History & Politics

Eyes of the Law

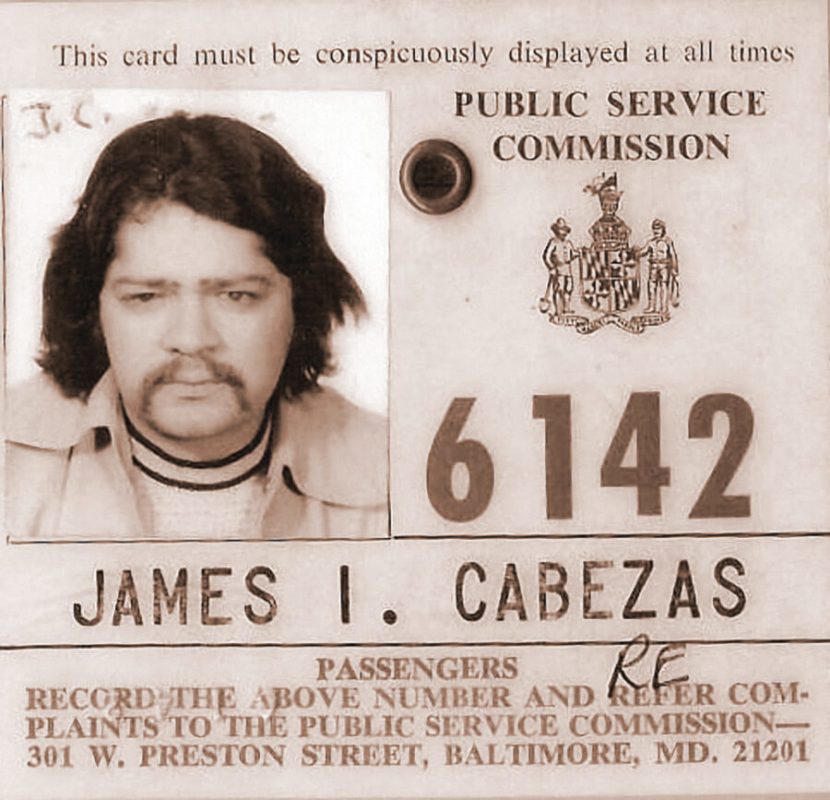

In new book, former undercover cop Jim Cabezas details his career fighting corruption and blindness.

“What does it profit a man to gain the whole world, yet forfeit his soul?”

-Inscription above the altar at St. Elizabeth of Hungary, Jim Cabezas’ boyhood church and school.

In 1971, Jim Cabezas’ rookie year walking a beat, there were 323 homicides in Baltimore. Twelve months later, a then-record 330. Heroin was sold openly, and he worked alongside more than a few, in his words, “brutal racists.” (Cabezas once threw his body on top of a black citizen getting savagely kicked by two officers, only to be told if he tried anything like that again he’d never receive backup.)

Less than two years on the job, Cabezas saw a grand jury return bribery indictments against six current and two former detectives. Indictments also came down against five lieutenants, six sergeants, and three patrolmen. Then former Governor Spiro Agnew resigned as vice president over extortion and other charges from his time in office in Maryland.

Recently, an older woman approached Cabezas, who just wrote his autobiography with former Sun reporter Joan Jacobson, and asked the former Baltimore cop and state political corruption investigator if he thought things had improved since be became a police officer. It should be noted: Cabezas spent three years working undercover as a taxi driver on The Block in the mid-’70s, and later, after losing his eyesight to a degenerative condition, oversaw the investigations that ended the tenures of former City Comptroller Jacqueline McLean, former Mayor Sheila Dixon, and former Anne Arundel County Executive John Leopold. “Probably the same,” the good-natured, matter-of-fact Cabezas told the woman. “Maybe worse,” he added, reflecting further.

The son of devout immigrants from Nicaragua and Chile, Cabezas grew up next to Patterson Park, attending St. Elizabeth of Hungary Catholic Church. His childhood was idyllic—baseball, football, and school—for a time. A near-fatal reaction to an antibiotic as a boy triggered a rare eye disease (which ultimately caused him to go blind in the middle of his career). Shortly afterward, he lost his mother to brain cancer. Then, as a cop, still only 22, his father—“my best friend”—was murdered.

Much of Cabezas’ 46-year career was spent in the chaotic Baltimore quadrant that includes The Block, City Hall, and police headquarters. Telling everyone he’d had enough and quit the department, in 1975, he actually went undercover for three years—posing as a taxi driver even to his future fiancée—and began frequenting The Block to determine if the Philadelphia mafia had infiltrated the prostitution, drug, gambling, and loan-sharking operations there. He also followed up on FBI concerns that the New York mob had infiltrated the docks and longshoreman’s union. Neither, he’d determine, had their hands in Charm City’s underworld. “Baltimore had a rep as a ‘rat town,’” he says. “Nobody kept an out-of-towner’s secrets, and it made the Philly and New York mobs nervous. Instead, it became a town where the mafia exiled people they didn’t kill.”

A chameleon with an unmistakable Highlandtown accent, he found corruption at each turn. “The culture on The Block is [drug] abuse and being abused, and it’s sad, but there is at least some honor among thieves. A few people look out for each other. With the police and with politicians, it’s just greed and hubris.”

After 15 eye surgeries, two well-timed minor miracles allowed Cabezas to maintain his near half-century pursuit of wrongdoers. The first was an offer to join the State Prosecutor’s office in the mid-’80s when his vision had deteriorated to where he couldn’t carry a gun. The second was new computer software for the blind that enabled him to stay on that job after a state doctor recommended his termination.

At 69, enjoying newfound renown from his book, he’s still surprised his corruption busts never served as a deterrent to others. He highlights, for example, former Baltimore County schools superintendent Dallas Dance, who went to jail last year. The other surprise was that his focus improved as he lost his eyesight over his career. “I listened better,” he says. “You can tell a lot from what’s in a person’s voice. I heard things with my heart I never saw before.”

Jim Cabezas with Joan Jacobson will be discussing his memoir Eyes of Justice at the Hamilton Branch (5910 Harford Road) of the Enoch Pratt Free Library on July 15 at 6 p.m