News & Community

Justice For All

Fifty years after Thurgood Marshall’s Supreme Court confirmation, Baltimore’s great dismantler of Jim Crow remains a colossus of U.S. history.

he closest Thurgood Marshall came to his own lynching was in Columbia, Tennessee, near the banks of the Duck River, a notorious repository of black bodies not far from the birthplace of the Ku Klux Klan.

he closest Thurgood Marshall came to his own lynching was in Columbia, Tennessee, near the banks of the Duck River, a notorious repository of black bodies not far from the birthplace of the Ku Klux Klan.

On the night of Nov. 18, 1946, Marshall, then chief counsel for the NAACP Legal Defense Fund, had just won the acquittal of “Rooster Bill” Pillow, a black man charged with rioting and attempted murder, and negotiated a lesser conviction for “Papa” Lloyd Kennedy, another black man charged with the same crimes. Months earlier, the first major post-World War II racial clash in the U.S. had broken out in Columbia after news spread of a fist fight between a white store clerk and a black veteran (who’d spoken up about the rude treatment his mother received after she complained of having to pay for a shoddy radio repair). Armed to protect themselves and the black section of town known as Mink Slide from white mob violence—the serviceman had been let out of jail and whisked out of Columbia for his own safety—Pillow and Kennedy were among more than 100 African-American men arrested following a standoff that left four white police officers with buckshot wounds.

Two of those arrested from Mink Slide were shot and killed by police while awaiting a bail hearing and, ultimately, 25 African-American men faced charges from rioting to attempted murder. For his safety and that of his small NAACP Legal Defense Fund team, Marshall had been driving the 50-plus miles back and forth from Nashville to the courthouse rather than staying in Columbia overnight. En route, they passed a typical “sundown town” warning sign each morning: N—GER READ AND RUN. DON’T LET THE SUN GO DOWN ON YOU HERE. IF YOU CAN’T READ, RUN ANYWAY!

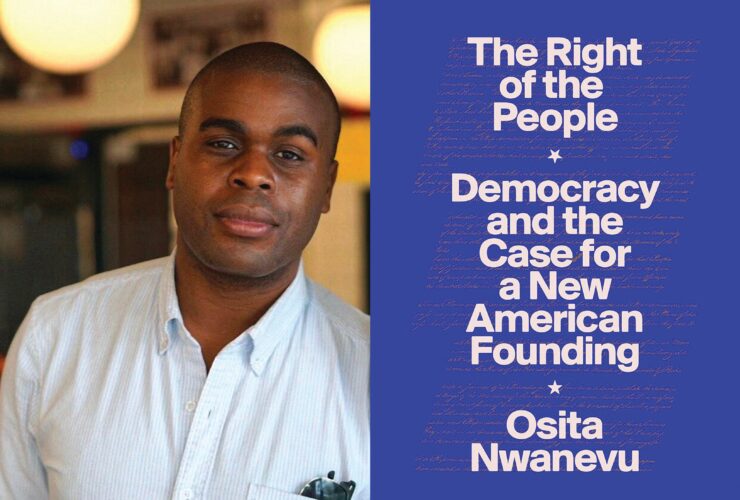

Marshall at the Supreme Court in 1955. —Getty Images

Amazingly, Marshall and his team would win acquittals in 23 of the 25 cases, some of which had been moved to a nearby county, from all-white juries. But they weren’t winning over everyone. By that evening in mid-November when Pillow was acquitted, some in the law-enforcement community, which often served as an extra-legal arm of the KKK—not to mention a lot of white Columbians—had had enough.

Just as the sedan Marshall was driving crossed over the Duck River Bridge on the return trip to Nashville, a car in the middle of the road blocked its path. Columbia police and highway patrol cars quickly surrounded Marshall’s vehicle with officers accusing Marshall of drunk driving. Marshall, who enjoyed a strong drink but was stone-cold sober at the time, was soon separated from the two attorneys and the journalist driving with him and ordered into the back seat of an unmarked vehicle.

Marshall was later saved only because fellow NAACP lawyer Alexander Looby whipped a U-turn after seeing the car carrying Marshall—supposedly headed to Columbia to face a judge for drunk driving—veer off the main road. Looby, with the other lawyer and journalist, both of whom were white, tracked the vehicle carrying Marshall down a dark dirt road and upset his abductor’s plans.

Marshall later recounted that he hadn’t been scared until the car he was in turned from the unpaved road toward the water, where, the NAACP lawyers had been told during the trials, they’d end up swinging from a tree. “The mob got me one night,” Marshall said in an interview years later, “and they were taking me down to the river where all of the white people were waiting to do a little bit of lynching.”

Eight years later, the Baltimore born-and-raised Marshall would become a household name—in white households—when he successfully argued Brown v. Board of Education before the U.S. Supreme Court and struck the death knell for the legal apartheid system of “separate but equal.” Marshall had long been a Joe Louis-type figure in black households by then. Across the Deep South, his arrival in town often marked the last, best hope for people of color in oppressed communities, many of whom would trek miles for a glimpse of the famous Negro lawyer in court. The answer to their prayers was recited with two words: “Thurgood’s coming.” And 21 years later—50 years ago this month—Marshall became the first African-American Supreme Court justice confirmed by the U.S. Senate. In the tumultuous 1960s, with cities erupting in police violence and riots, it was a moment akin to the election of President Barack Obama in the black community. “Every bit as important,” says Ben Jealous, the former head of the NAACP and current candidate for governor in Maryland, “because it came in 1967 in the midst of the civil-rights struggle and a lot of upheaval in this country.”

Today, Marshall’s legacy inevitably gets reduced to his victory in Brown v. Board of Education and his identification as the first black justice to serve on the Supreme Court. The Columbia, Tennessee, episode, and dozens of others like it, remain forgotten or unknown altogether. But in a legal career that spanned nearly sixty years, it was the two groundbreaking decades leading up to Brown v. Board of Education during which Marshall—as courageous, tenacious, and visionary an individual as this country has ever produced—changed America.

Traveling nearly 50,000 miles each year, mostly by train, often alone, his life threatened too many times to count, Marshall took Jim Crow apart plank by plank, state by state, federal ruling by federal ruling. Overseeing hundreds of cases as director of the NAACP Legal Defense Fund for 21 years, Marshall set precedent after precedent, not just in the arenas of education and criminal law, but across every sector of public life—voting, housing, transportation, equal pay, taxpayer-funded services, military justice, higher education, and the rights of minorities to serve on juries.

Three examples: Marshall helped establish that coerced confessions are not admissible in court; that states cannot legally enforce restrictions on the sale of homes to minorities; and that nonwhites cannot be barred from voting in primary elections, which, in many parts of the country, were the only votes that mattered.

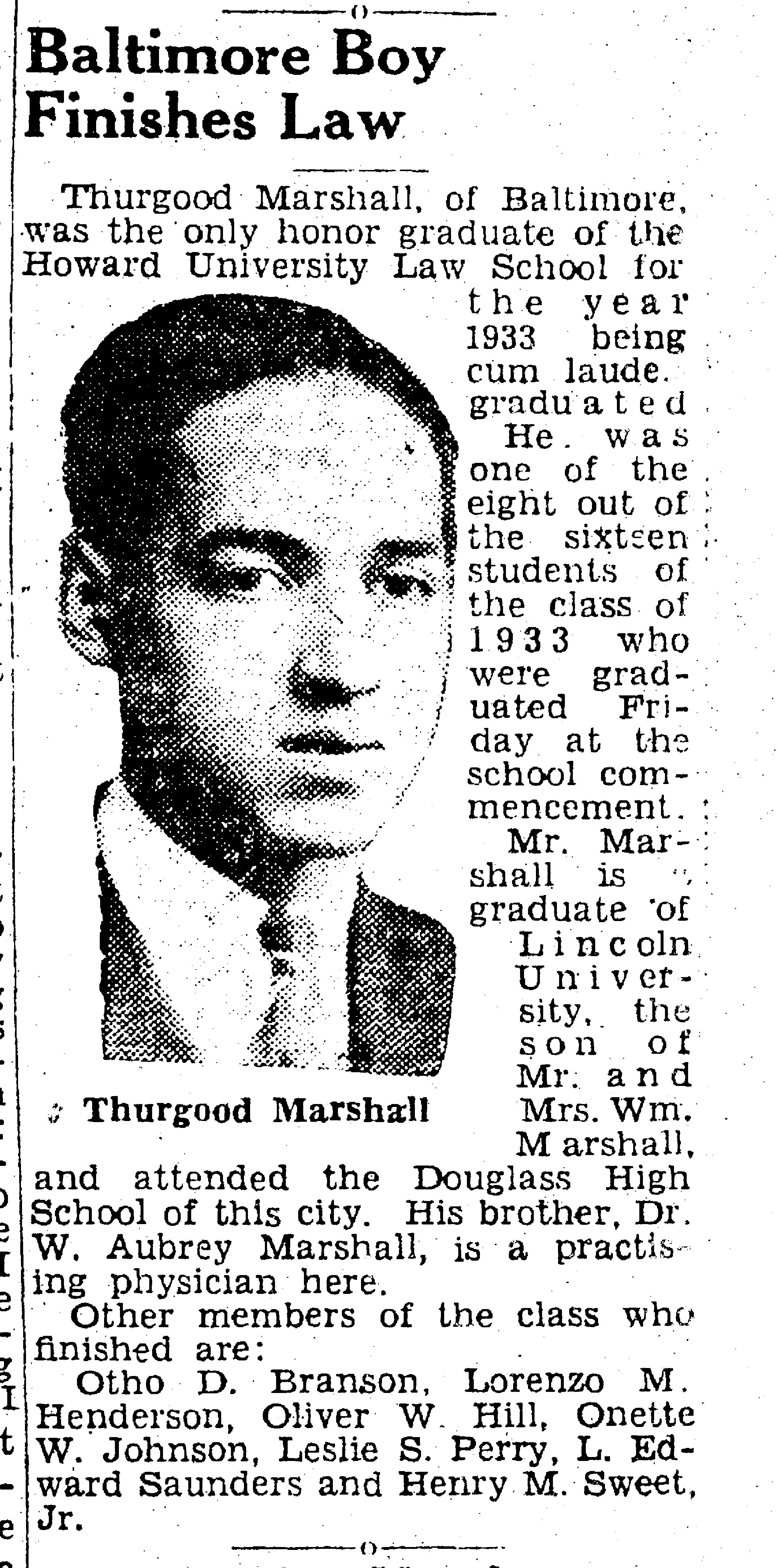

Marshall finishing law school. —Afro-American Newspapers

“Before Thurgood Marshall, ‘All men are created equal’ were just [hollow] words,’” says Sherrilyn Ifill, who holds Marshall’s position today as the head of the NAACP Legal Defense Fund. “He gave them meaning.”

Thurgood Marshall grew up in historic West Baltimore, in the then-black middle-class neighborhood of Upton, in a red-brick, three-story Division Street rowhouse that still stands. Public School 103, the former “colored” elementary school he attended, stands, too, but has been long vacant and was badly damaged by fire last year. His family roots run deep here: Three of Marshall’s grandparents lived in Baltimore at the start of the Civil War. All were literate and became advocates for black equal rights.

One grandfather, Isaiah Olive Branch Williams, volunteered and served as a captain’s steward aboard the U.S.S. Santiago de Cuba during the Civil War, seeing combat against the Confederate navy. He later opened a Baltimore grocery store, which he operated as long as he lived, and joined with prominent local African Americans in a campaign against police brutality and discrimination in 1875.

Marshall’s other grandfather, Thorney Good Marshall, was the only one of his grandparents who was not free when the Civil War broke out. Not yet an adult, he escaped slavery in Virginia during the chaos and made his way to Baltimore, which had the largest population of free blacks in the country. Thorney Good Marshall joined the U.S. Cavalry after the war, heading west with one of the all-black regiments nicknamed “Buffalo Soldiers” by Native Americans. He also later opened a successful grocery store in Baltimore. (Marshall’s name derives from a great-grandfather, “Thorough-good,” which he shortened to Thurgood in second grade, believing it too lengthy to write.)

Marshall’s father, Willie, worked as a B&O Railroad porter and as a waiter at the white-only country club on Gibson Island—and helped his son land work both as a porter and waiter, experiences that would leave an impression on the younger Marshall. His mother, Norma, graduated from what is now Coppin State University after her two sons were born and taught in a local “colored” elementary school.

It was from this lineage, and in the crucible of segregated West Baltimore—a Harlem-like mecca of political activism, achievement, and black culture (Marshall went to school with Cab Calloway)—that Marshall’s worldview took shape. For decades, national civil-rights leaders, including Marshall’s friend Clarence Mitchell Jr., the NAACP’s chief lobbyist in Washington during the 1960s, would rise from West Baltimore, which had been home to the forerunner of the NAACP, the Mutual United Brotherhood of Liberty, and then home to one of the strongest branches of the NAACP.

But as much as anything, it was the kitchen-table debates with his father about the Constitution, race relations, and current affairs that sparked Marshall’s interest in the law. His older brother Aubrey—not nearly as contentious—would go on to medical school and become a doctor. But Marshall, who liked to banter and enjoyed a good argument his whole life, engaged his father, a well-read, complicated, sometimes tough man without the benefit of a high-school education, for hours. Marshall later said his father, who demanded he prove every claim he made in heated discussions sometimes overheard by neighbors, “never told me to be a lawyer, but he turned me into one.”

Marshall’s mother, it’s said, wanted him to become a dentist because it guaranteed a middle-class income. His grandmother, too, worried a black attorney was doomed to struggle in Baltimore—which Marshall did at first, unable to find someone who’d rent a downtown office to a “colored” professional. She taught him to cook before he left for college. “You can pick up all that other stuff later,” she told her grandson, “but I bet you never saw a jobless Negro cook.”

The lessons and concerns were not lost on Marshall. He loved good food, developed a capable touch in the kitchen, as well as in the courtroom, and never forgot where he came from. His mother also came around: She pawned her wedding and engagement rings to pay his law-school entrance fees to Howard University. It proved a fortuitous landing place for Marshall, who had not bothered applying to the University of Maryland law school, located just a mile and a half from his home.

Maryland did not accept black students when Marshall graduated from Lincoln University in 1930 and it was with some rich irony that his first major civil rights victory—shortly after earning his law degree from Howard and passing the Maryland state bar—was putting an end to the school’s racist admission policy.

“Marshall could not have gone to a better school,” says Kurt Schmoke, the former Baltimore mayor, former Howard law dean, and current president of the University of Baltimore. “His dean, mentor, and teacher at Howard was Charles Hamilton Houston, who viewed the law school as the West Point of the civil-rights movement and he was training the foot soldiers.” Houston, notably, left Howard not long after Marshall’s graduation to become the first special counsel for the NAACP and soon hired Marshall. “If you asked Marshall, he’d tell you it was Houston’s strategy to defeat segregation by attacking ‘separate but equal,’” says Schmoke.

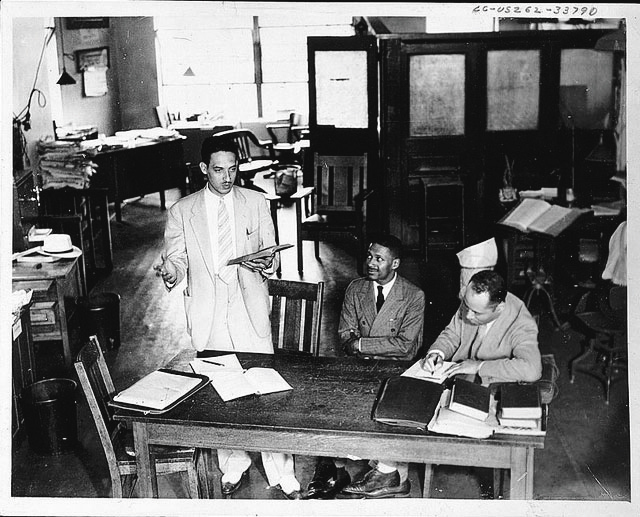

Marshall following the University of Maryland Case. —Afro-American Newspapers

Seven days after Thurgood Marshall became a certified Maryland lawyer on Oct. 11, 1933, George Armwood was lynched in the town of Princess Anne in Somerset County. Twenty-two or 23 years old when he was murdered, Armwood was described by friends as “a hard worker, uncomplaining, quiet,” well liked, but also “feeble-minded.” He had been accused of attempted assault and rape of a 71-year-old woman two days earlier. Before he was hanged, Armwood’s ears were cut off and his gold teeth were ripped out. His corpse was dragged back to the courthouse in downtown Princess Anne, hung from a telephone pole, and then burned and dumped in a local lumber yard.

The morning after Armwood’s death, Marshall wrote to Houston about the lynching. Already sizing up the legal situation and laying out the broader politics at play, the 25-year-old Marshall mentioned that the judge involved in the case and the Maryland governor were of different political parties and (correctly) predicted those competing political interests would keep the issue alive as the governor, law-enforcement leaders, and the justice system passed blame. A week after the killing, Marshall and nine other lawyers sent a petition to Gov. Albert Ritchie seeking anti-lynching legislation and an investigation into the lynching and state police involvement—Armwood had been taken by law enforcement officers to Baltimore City at one point for his own protection only to be inexplicably returned to the Eastern Shore.

Twelve men eventually were named members of the lynching mob, although none was found guilty of any crimes. Armwood, however, was the last man lynched in Maryland.

The Armwood case and a handful of others galvanized Marshall, who was struggling to establish a stable practice in Depression-era Baltimore. He soon turned his full attention to civil-rights law. Although the civil-rights cases rarely paid, there was plenty of work and Marshall proved particularly well suited to it. As a young porter with the B&O Railroad and a waiter on Gibson Island, he’d had the opportunity to interact with black and white people from all walks of life and he learned to size up individuals and situations, which was especially important in the segregated South, where laws, written and unwritten, varied from city to county to state.

Marshall was also a rare combination in terms of personality. He was someone both unpretentious and humble—he didn’t tout his own accomplishments—and gregarious, sharp-witted, loud, and funny. He was equally as quick to give others credit as to share a bourbon, an off-color joke, and a story or two. In the courtroom, he made his case with facts, the law, and the Constitution in a frank manner, neither alienating juries, Southern judges, nor opposing counsels, with whom he generally got along.

“Marshall was somebody naturally at ease in his own skin his whole life and optimistic. He liked and understood how to get along with people,” says University of Maryland law school professor Larry Gibson, who met Marshall on several occasions, and authored Young Thurgood: The Making of a Supreme Court Justice. “He was also resilient, knew how to find the silver lining in things, even in cases he would lose. But he was not naïve. Not by any means.”

It was only 19 months after passing the state bar that Marshall found the right candidate, an aspiring attorney and Amherst College graduate named Donald Murray, to use as a vehicle in tackling the University of Maryland law school’s admission policy. Both Marshall and Murray were threatened during the court challenge by the local KKK, which wrote Marshall and informed him that he was their “number one” target. (Murray went on to fulfill Marshall’s faith in him, too, graduating in 1938 and getting involved in several subsequent cases that led to the integration of other University of Maryland graduate schools.)

The Maryland law school’s long refusal to admit blacks, including himself, remained a deeply personal affront Marshall’s entire life and he was noticeably absent from the dedication when the school named its law library after him in 1980.

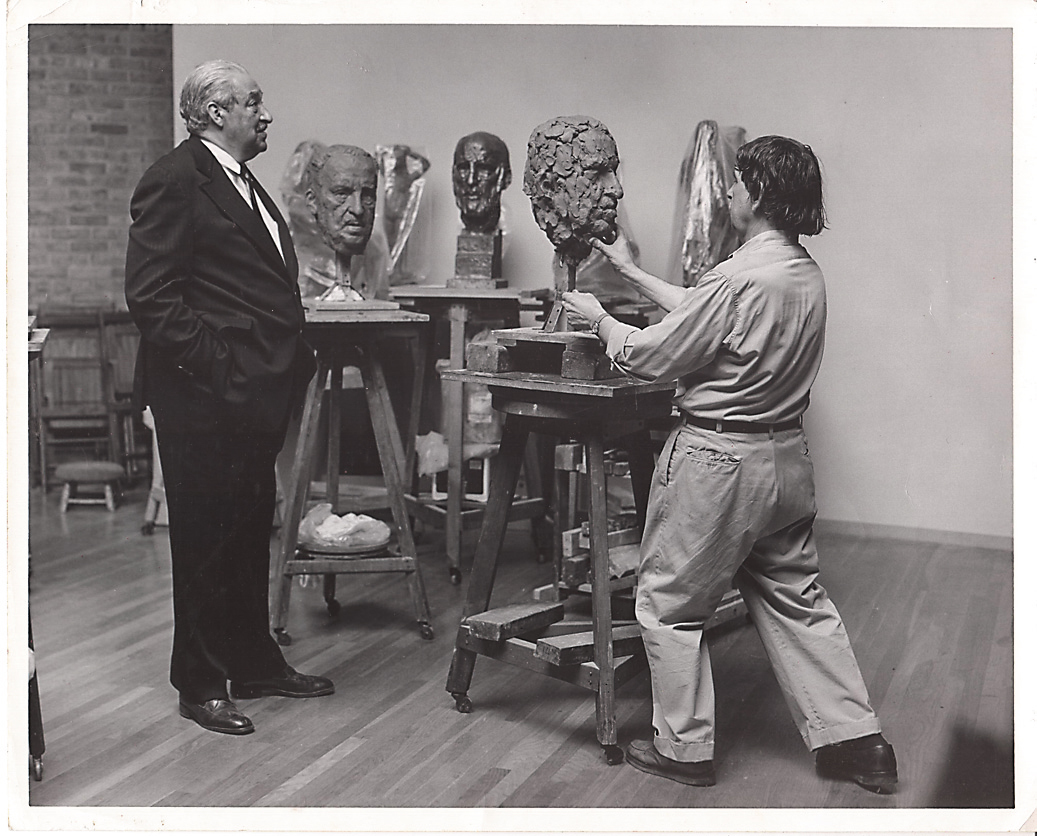

Marshall posing for his Maryland Law Library Bust. —Cecilia Marshall

After the Maryland law school victory, which Marshall won because the state failed to make its “separate but equal” defense—there was no black law school in Maryland—Marshall began representing black teachers in the state, who typically received half the pay white teachers earned. In 1938, Marshall won the first equal-pay cases in the nation for black teachers in Montgomery and Anne Arundel counties, prompting the Maryland legislature to appropriate equal pay statewide. That same year, the NAACP named him chief counsel and he moved to New York with his first wife, Buster. (She died of cancer, and in 1955 Marshall remarried and had two children, Thurgood Jr. and John, who survive to this day along with his 89-year-old second wife, Cissy.)

That second major civil-rights victory over teacher’s pay opened the door to similar battles all across the South in the ensuing decade, where Marshall and the NAACP Legal Defense Fund filed equal pay litigation in nearly every state—sometimes in several jurisdictions within each state. The Columbia crisis, for instance, wasn’t Marshall’s first foray into Tennessee. In the early 1940s, he had fought teacher pay cases in Nashville, Jackson, and Chattanooga.

Meanwhile, Marshall kept implementing the multi-pronged attack to end segregation as well as racially discriminatory criminal justice practices. Marshall was just 32 years old when he won his first Supreme Court victory in Chambers v. Florida, in which the Court overturned the convictions of four black men who had been beaten and coerced into confessing to a murder. Four years later, in what he considered one of his most important precedent-setting cases, Smith v. Allwright, Marshall convinced the Supreme Court to strike down the Texas Democratic Party practice of excluding blacks from primary elections of political parties, which had previously been viewed as private organizations. Another was Morgan v. Virginia, in which Marshall convinced the Court to strike down segregation on interstate buses after Baltimore native Irene Morgan, a 27-year-old mother of two, refused to give up her seat.

Between 1940 and 1961, he won 29 of the 32 cases he argued before the U.S. Supreme Court. Meanwhile, one of Marshall’s toughest tasks and moral quandaries became deciding where to put his effort. As Marshall was following his and Houston’s grand strategy to poke holes in Plessy v. Ferguson—the 1896 Supreme Court decision that gave birth to the legal doctrine of “separate but equal”—pleas kept coming to the NAACP to aid in capital punishment cases.

“Eventually, almost all of the criminal cases that Marshall gets involved in are death-penalty cases,” says Gibson. “He’s having to pick and choose his cases wisely. On one hand, he’s got a strategy he’s following to tear down segregation. But he’s also trying to step in where he has a chance to save someone’s life.

“At the same time, he’s having to stay in places under assumed names, staying in different private homes each night—sometimes alerting the press of his travels because he believes that will help protect him.” In one of the most notorious cases Marshall took on, the director of the Florida NAACP and his wife were killed in a firebombing of their home on Christmas night.

It’s also worth noting that on the way to Brown v. Board of Education, Marshall and the NAACP Legal Defense Fund made two momentous changes in their game plan.

“He’s also trying to step in where he has a chance to save someone's life.”

Initially, they’d set out working to enforce the “separate but equal” provision of Plessy v. Ferguson by demanding equal teacher pay and school facilities, hoping to make things better for African Americans until separate but equal became too expensive for the state to maintain. By the mid-1940s, however, their argument had taken another step: Because separate but equal facilities had never truly been accomplished—public services for blacks were uniformly inferior—the only solution, Marshall began to argue, was to make all public facilities and services open to all races.

By 1949, Marshall and the NAACP Legal Defense Fund’s argument evolved again as they began seeking direct test cases against public school segregation. Five of those test cases were eventually consolidated into Brown v. Board of Education, in which a three-judge panel at the U.S. District Court level had originally found “no willful, intentional or substantial discrimination” in the Topeka, Kansas school system.

But Marshall, as chief counsel, argued before the Supreme Court that racial classifications and segregation were inherently unconstitutional—regardless of the equality of the facilities—in that they stigmatized African-American children, thereby denying them equal protection under the law as guaranteed by the 14th amendment.

When asked during the Brown arguments by Justice Felix Frankfurter what he meant by “equal,” Marshall responded in the same forthright, plainspoken manner that had become his hallmark.

“Getting the same thing, at the same time, and in the same place,” he told Frankfurter.

In 1961, President John F. Kennedy appointed Marshall to the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit. By that point, Marshall was ready for a change. “I’ve always felt the assault troops should never occupy the town,” he said. “I figured after the school decisions, the assault was over for me.”

Four years later, President Lyndon B. Johnson appointed him U.S. Solicitor General and, in 1967, associate justice of the Supreme Court.

It is a footnote in history that Johnson was so intent on appointing the first black justice he created an opening on the court by naming Ramsay Clark attorney general in early 1967. That move essentially forced his father, Supreme Court justice Tom Clark, to resign because of a conflict of interest.

Marshall’s nomination became a summer-long fight before he was finally confirmed on Aug. 30. The final vote was 69-11 with Johnson persuading 20 senators, who feared a vote for a black man to the Supreme Court would cost them a subsequent election, to abstain.

"He was the kind of person that if a friend of mine from college stopped by, I’d check to see if he was in the office, and if he was, he’d say hello and talk to a complete stranger for 15 minutes. He was open to everyone.”

Marshall joined the generally like-minded liberal Warren Court, but then became known as “the great dissenter” as the court shifted to the right under chief justices Warren Burger and William Rehnquist. His reputation as a curmudgeonly old judge grew over his 24 years on the bench, but, according to his clerks, that reputation was only his public persona. Underneath, they say, he remained warm and big-spirited.

Former law clerk Stephen Tennis recalls barbecues at the Marshall home in Northern Virginia with his wife, Cissy, and their two sons, Goodie and John. “He was a very informal man,” Tennis says. “We called him ‘boss’ or ‘judge,’ but never ‘Justice Marshall.’ He was the kind of person that if a friend of mine from college stopped by, I’d check to see if he was in the office, and if he was, he’d say hello and talk to a complete stranger for 15 minutes. He was open to everyone. It didn’t matter who you were. But he didn’t suffer fools, either, which to him were people who thought a lot of themselves.”

Georgetown University professor Sheryll Cashin, another former law clerk, and the author of Loving: Interracial Intimacy in America and the Threat to White Supremacy, says Marshall’s vision of equality wasn’t limited to African-Americans, but to “any individual or minority group oppressed by the majority or by the government, and that included women, the physically challenged, and criminal defendants.

“I think some people are still adjusting, or not adjusting, as it were.”

At the press conference announcing his retirement in 1991, Marshall, true to form, was irascible, playful, and quick to the point as he fielded questions from the media.

“What’s wrong with you, sir?”

“What’s wrong with me?” Marshall echoed. “I’m old. I’m getting old and coming apart.”

Later, a reporter asked about a recent quote in which Marshall said despite a lot people quoting Martin Luther King’s “Free at last” statement, he still didn’t feel free.

“All I know is that years ago when I was a youngster, a Pullman porter told me that he had been in every city in this country, he was sure, and he had never been in any city in the United States where he had to put his hand up in front of his face to find out he was a Negro,” Marshall said. “I agree with him.”

Marshall refused to answer questions about other justices, the make-up of the court, and issues facing the court. When asked how he wanted to be remembered, he responded simply, “That he did what he could with what he had.”

Finally, another reporter mentioned to Marshall that several of his law clerks over the previous few days had been asked what they learned from him. The reporter informed Marshall that each had responded that they had developed a greater understanding of the rights of the individual from the justice. The reporter then asked Marshall if he could talk about what he had tried to pass on to them. “If there is one thing this court is for,” Marshall replied, “it is for human rights.”