History & Politics

Recalling the “Lost” Irish Quarry Town of Texas in Baltimore County

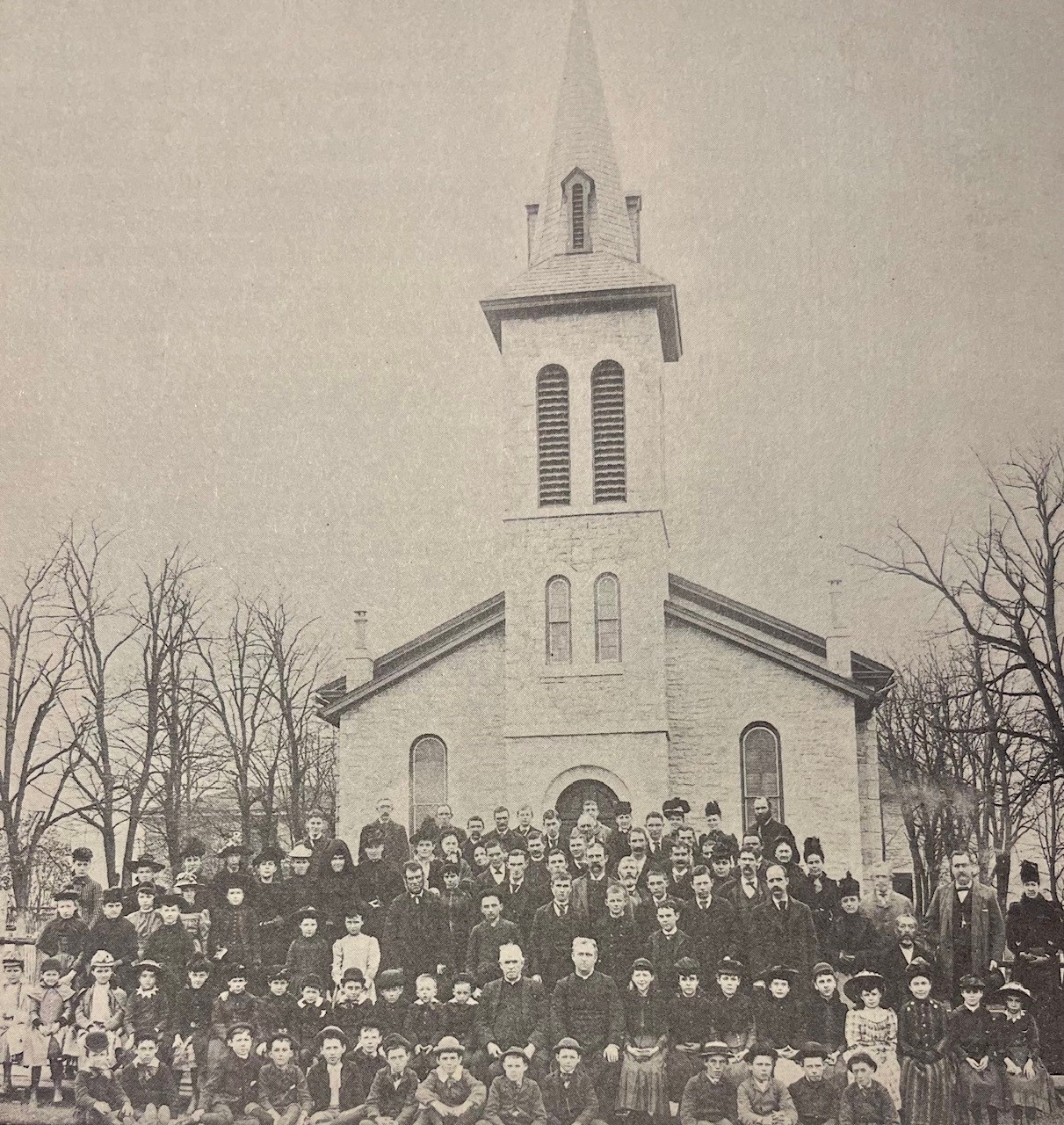

St. Joseph’s Roman Catholic Church in Cockeysville was constructed between 1850-1852 by the Irish arrivals.

At the height of the Great Famine in 1847, some 1,500 Irish tenant farmers and their families were evicted from their land and made to walk 165 kilometers along the Royal Canal from County Roscommon to Dublin. Among them were 366 men, women, and children—mostly children, in fact—from the village of Ballykilcline, which was in the 13th year of a rent strike against the British Crown.

The Queen’s calvary and police “tumbled” their thatched homes, dispatching them en masse to Liverpool and then New York as part of a forced migration scheme to steal their farms. Officials had labeled the Ballykilcline families “troublemakers,” as neighboring tenants, many of whom had lost loved ones to starvation and famine disease, also began refusing to pay their rent.

Today, their sorrowful trek is marked by 30 pairs of bronze shoe sculptures on the National Famine Way walking trail from County Roscommon to Dublin. (The small bronze statues were cast from a child’s weathered shoes, later discovered by a farmer in a ruined 19th-century cottage.)

In a twist of fate, many of these Ballykilcline survivors would end up in Baltimore County, where they would establish an Irish community with the unlikely name of Texas around a promising quarry and the burgeoning North Central Railway line.

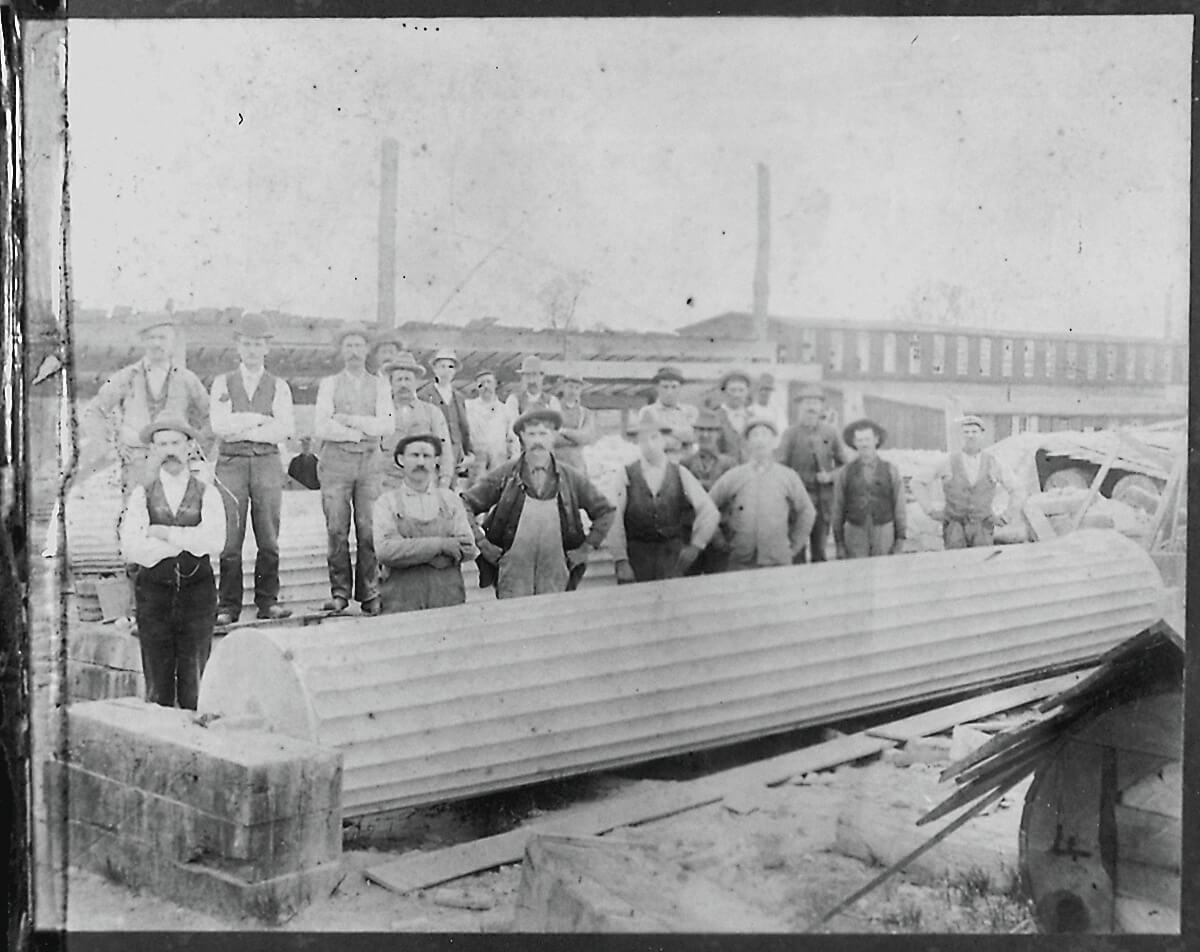

The crystalline, blue-white dolomite marble quarried by some of these Irish workers would eventually be used in the construction of the Washington Monument in D.C., the porticoes of the U.S. Capitol, City Hall, and, poignantly, the spires atop St. Patrick’s Cathedral in New York. If you live in a 100-year-old rowhouse, your marble stoop may have been quarried by these Ballykilcline refugees—or their descendants.

Similarly, Texas marble helped the Irish arrivals build the quarry adjacent St. Joseph’s Roman Catholic Church between 1850 and 1852. Some of their headstones, indicating the year of their birth in Roscommon County, can be found in the cemetery behind the still-thriving church.

How exactly the village, which has all but disappeared, like several other former industrial and mill towns in Baltimore County—including Ashland, Oregon, Gunpowder, and Warren—got the name Texas remains a question. The best guess is it originates from volunteers who left the nascent village in 1846—the year before the Ballykilcline migrants arrived—to fight in the Mexican War. When they returned, they named the town Texas, initially New Texas, because it apparently reminded them of the Lone Star State.

By 1895, the Irish were well established, with the formerly evicted families able to buy small plots of land and houses made affordable by ground rents.

“Everyone’s heard of the ‘No Irish Need Apply’ signs,” says Cassie Kilroy Thompson, a local public historian of Roscommon descent. “In Texas, it went the other way: ‘Only Irish Need Apply.’”

In March of that year, The Sun ran a detailed description of St. Patrick’s Day festivities in Baltimore County, including close-knit Texas, entitled “Ireland Forever!” (Éirinn go Brách in Irish). The 1940 Census listed Texas with a population of 494, including 111 dwellings, three farms, eights businesses, one school, two churches, one public building, two industrial plants, one cemetery, and one amusement park.

But by then, mechanization was reducing the need for quarry workers, and the land around the quarries became more valuable for commercial development. In 1951, the Texas post office closed, with mail going through increasingly sprawling Cockeysville, which eventually subsumed Texas entirely. Outside of the church, cemetery, and quarry—operated now by Martin Marietta—few markers remain. A notable exception is Padonia Road, named for Richard Padian, one of the Ballykilcline rent strike leaders and among the first to make his way to Baltimore County with his wife, Mary, and their four children.

The secular heart of Texas—McDermott’s “Don’t Worry About It” Tavern, down the street from St. Joseph’s on Church Lane—held on until 1991. That’s when former quarryman, professional boxer, and longtime owner of the legendary tavern, James McDermott, finally sold his bar to make way for the Light Rail. Known as the “Unofficial Mayor of Texas,” he once said the reason he didn’t sell the place and retire earlier was that, as a lifelong bachelor who lived above the bar, he never had to worry about being lonely.

“All I have to do is walk down the steps,” he said in an interview, “and I’m with all my friends.”

Interestingly, St. Joseph’s, like many Catholic churches, again has a large immigrant congregation—with numerous Mexican and Central American families among its 7,000 members.

Even so, those congregations (including those founded by Irish refugees) occasionally need a reminder of the Christian principle of “welcoming the stranger.”

“We try to make the connection this has always been an immigrant church,” says Msgr. Richard Hilgartner. “The marble for the new sanctuary arch is coming from the old quarry.”