History & Politics

Decades Before the Civil War, Maryland Funded a Colony in Liberia to “Resettle” Free African Americans

The bonds between the country we know as Liberia, uniquely allied with the U.S. since its inception, and Maryland are profound, if generally little known.

Stephen Allen Benson was six years old when he emigrated to West Africa. Born on Maryland’s Eastern Shore in 1816, he sailed from Baltimore on a brig named Strong with his free-born African-American parents and four older and two younger siblings. His father, a 36-year-old Cambridge farmer, and mother, a 30-year-old weaver, no doubt had high hopes for themselves and their children when they departed the Baltimore harbor.

Though not enslaved, the Benson family was part of a group of 37 leaving behind the brutal racism endemic to the country of their birth for the promise of life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness in the fledgling private colony of Liberia (literally “land of freedom”).

Motivated by the domestic politics around slavery and their own white nationalism, prominent Southern white Americans, including Maryland lawyer Francis Scott Key, had founded the American Colonization Society several years earlier. As an alternative to emancipation and citizenship, their answer to the growing “problem” of free Black Americans was “resettlement” in Africa.

Things took a tragic turn for the Bensons, however, after landing in Monrovia on Aug. 8, 1822, as it did for so many of their fellow passengers. Most of the African Americans aboard ships funded by the American Colonization Society would die from malaria and disease and in confrontations with the native West African populace. Stephen’s mother succumbed to disease three years after their arrival. Four of the Benson children died similarly over the ensuing two years. Underscoring the inevitable contentiousness of colonializing inhabited land, 16-year-old Joseph Benson was shot to death months after arrival by what his brother Stephen described as “an attack of the natives.”

Maryland, with other slave states, including Mississippi and Kentucky, later formed its own resettlement colony under the American Colonization Society umbrella in what is today’s Liberia. In fact, after seceding from the American Colonization Society, the short-lived Republic of Maryland—now the Maryland County in Liberia—became an independent country. More than half of the African Americans who ultimately emigrated to Liberia were emancipated on the condition of deportation to West Africa.

Stephen Benson would survive and, emblematic of Liberia’s settler colonialist roots, become the nation’s second president after it declared independence from the U.S. in 1847.

HE BELIEVED IT WAS BETTER TO “DIE IN MARYLAND THAN BE DRIVEN LIKE CATTLE TO…LIBERIA.”

Not surprisingly, Liberia has struggled with its dual heritage—a mix of minority Black Americo-Liberian settlers and indigenous Africans—since the constitution, “For the Government of the African Colony of Liberia,” was written 100 years ago.

“Liberia continued to mean different things to different people,” writes Claude Clegg, a Black historian of the African diaspora at the University of North Carolina, in The Price of Liberty: African Americans and the Making of Liberia. “Those who had come from America looking for liberty sometimes found a semblance of what they sought, but very few discovered absolute freedoms untampered by hardships and sacrifice.”

For many, however, it was worth the risk. “Particularly, for ex-slaves,” Clegg writes, “freedom meant legalized personhood, civil rights, and a documented existence. In essence, it was the unfettered ability to create one’s own familial, communal, and civic relations in a land beyond the overbearing control of white people.”

The role and identity of free and formerly enslaved African Americans evolved quickly in Liberia, taking a complex, empowering, but also surreal turn. With support from their U.S. backers, the Americo-Liberians constructed a replica of the antebellum society they had fled, oppressing the native population and denying them the right to vote, which still has political reverberations in Liberia.

“The Americans, in this case, are repeating what global, British colonizers did,” says local historian Lou Fields, author of Freedom Seekers: Early Abolitionists in Antebellum Baltimore. “Britain laid down a philosophy that says go somewhere, take somebody’s land, call it yours. Put people in charge, give them all the guns, and they’ll make the rules and regulations and tell the poor people, ‘You’re just a laborer, you don’t have much say.’ Unfortunately, we still see that elsewhere in the world today.”

The bonds between the country we know as Liberia, uniquely allied with the U.S. since its inception, and Maryland are profound, if generally little known. Stephen Benson was followed in office by Daniel Warner, who was born in Baltimore County to a formerly enslaved person and departed with his father and family aboard the Oswega, arriving in the teetering settlement of Monrovia in 1823.

Liberia’s capital, with a population of more than a million people today, Monrovia was named 100 years ago this month for then-President James Monroe, one of the largest slaveholders in the U.S. at the time and a staunch colonization advocate. (In a 442-page memorandum to Congress in 1845 from slaveholding President John Tyler, Black Americans emigrating to Liberia were documented as “recaptured Africans.”)

It was not until 1904, after Baltimore-born Garretson Gibson, who emigrated in 1845 and served a four-year term in office, that Liberia saw its last American-born president. Other prominent Americans who supported the colonization movement included Speaker of the House Henry Clay, Secretary of State Daniel Webster, and President Abraham Lincoln, whose views on race would evolve during the Civil War.

Johns Hopkins made a small, one-time donation to the cause. John McDonogh, in whose name the McDonogh School was founded in Owings Mills, refused to free those he enslaved unless they agreed to deportation to Liberia. He eventually sent 118 formerly enslaved individuals to West Africa on American Colonization Society ships as part of an incentivized manumission “work” program on his New Orleans plantation.

The motivations behind those who supported colonization efforts are not easily unpacked 150-200 years later. Some could no longer tolerate slavery but, believing freed African Americans could not make it in a white society, viewed their “return” as a moral effort. Others recognized that slavery was a doomed institution and preferred deportation to citizenship. Meanwhile, slaveholders simply did not want free Black individuals near enslaved African Americans, fearing they’d encourage escape—or worse, revolt.

Frustrated with the pace of colonization, which he said would take “centuries,” McDonogh proposed a 50-year “removal” plan akin in theme to the infamous Trail of Tears. In an April 1830 letter to his friend, Louisiana Sen. Edward Livingston, McDonogh suggested marching free Black Americans to the Northwest Territory—similar in concept to the removal of Native Americans from the South, which would begin the following month and last two decades:

“How would it accord, Sir with your ideas, to have the country belonging to the U.S. on the North West Coast set aside by law as an asylum or place of refuge for the free people color of the United States where they might establish either a government of their own or become a state of the union forming a part of the American confederacy.”

In the U.S., the colonization effort had the opposite effect intended by its slaveholding founders—it galvanized early abolitionists. In the eyes of former Morgan State University historian Benjamin Quarles, the colonization movement “originated abolitionism,” arousing the free Black community and slavery opponents. The overwhelming majority of 19th-century African Americans saw through the embedded racism of the era’s white liberalism.

In his pioneering book, Black Abolitionists, Quarles makes the case that the “colonization scheme had a unifying effect on Negroes in the North, bringing them together in a common bond of opposition.” Certainly, it had that effect in the Washington and Baltimore area.

“There might have been a little support for colonization initially [in the Black community],” says Scott Shane, author of Flee North: A Forgotten Hero and the Fight for Freedom in Slavery’s Borderland, whose protagonist, Thomas Smallwood, supported colonization before his 1831 manumission and then reversed his stance. “I suspect Smallwood might have been influenced by Black abolitionist writer David Walker in this famous [1830] essay in which he denounces colonization in the strongest terms. I think there was a change of heart in the Black community, at least in Washington and Baltimore. There are recorded public meetings where people basically get together and say, ‘Screw these people.’”

The brig Strong was not the first the American Colonization Society sent to West Africa. Two years earlier came the Elizabeth, which carried 86 emigrants, including the Rev. Daniel Coker, a remarkable figure in the history of the Black church in the U.S. and eventually, West Africa.

An African American of mixed heritage born into slavery in Baltimore, Coker, after gaining his freedom, served as the first official pastor of the historic Bethel African Methodist Episcopal Church on Druid Hill Avenue. Arriving initially in Sierra Leone, where the British had formed a colony of free and formerly enslaved Black individuals in Freetown, Coker became one of the founders of the West African Methodist Church.

Remarkably, the journal he kept of his voyage, chronicling his seasickness and then his heartbreak after learning of the death of nearly 400 enslaved Africans aboard a captured Spanish slave ship, survives to this day. So do letters to his wife, mother, and brother in Baltimore from his earliest days on West African soil. In one dispatch to his brother, he writes his group has met “such trials” and that only a handful of his cohorts remained together, and provisions were running low. He refers to his new home as “a strange heathen land,” adding he had not heard from America and does not know whether more people or provisions will be sent. He admits he does not know “what is to become of us, far distant from my dear family and friends,” but his faith in his mission and God is steadfast. Coker implores everyone who is able to follow his path:

“If you ask my opinion as to coming out—I say, let all that can, sell out and come; come, and bring ventures, to trade, etc. and you may do much better than you can possibly do in America, and not work half so hard. I wish that thousands were here, and had goods to trade with. Bring about two hogsheads of good leaf tobacco, cheap calico, cheap handkerchiefs, pins, knives and forks, pocket knives, etc.; with these you may buy land, hire hands, or buy provisions. I say come—the land is good…”

Interestingly, William Watkins, who attended and later ran the Bethel Charity School in Baltimore which Coker founded, rejected the invitation. He became, with Frederick Douglass, among others, one of colonization’s most vocal opponents.

In 1827, Watkins penned a letter to Freedom’s Journal urgently reminding readers that many prominent colonization supporters were slaveholders who wished to remove the influence of free Blacks on those enslaved. He also wrote anti-colonization and anti-slavery essays for the Baltimore newspaper Genius of Universal Emancipation while becoming acquainted with journalist and abolitionist William Lloyd Garrison, who had initially supported colonization. Garrison credited Watkins with changing his views and their relationship linked Baltimore’s Black community with the larger abolitionist movement.

Watkins believed it was better to “die in Maryland, under the pressure of unrighteous and cruel laws than be driven like cattle to the pestilential clime of Liberia.”

It goes without saying, even free Black men and women in Maryland did not have statutory guarantees of their rights before Emancipation. (Watkins, like so many liberty-seeking African Americans, eventually emigrated to Canada.) They could not vote, testify in a trial, or sit on a jury. They paid taxes, but their children could not attend public school.

The laws in Maryland, and elsewhere in the South, worsened after the 1831 Nat Turner slave rebellion in neighboring Virginia. In May 1832, the General Assembly banned free African Americans from other states from moving to Maryland—and prohibited free African Americans from returning to Maryland after leaving for employment elsewhere. New legislation denied free African Americans in Maryland from owning firearms without permission from local officials.

By the end of the decade, the state passed legislation that could, for all intents and purposes, re-enslave free African Americans by permitting courts to sentence forced servitude for debts, vagrancy, and some criminal convictions.

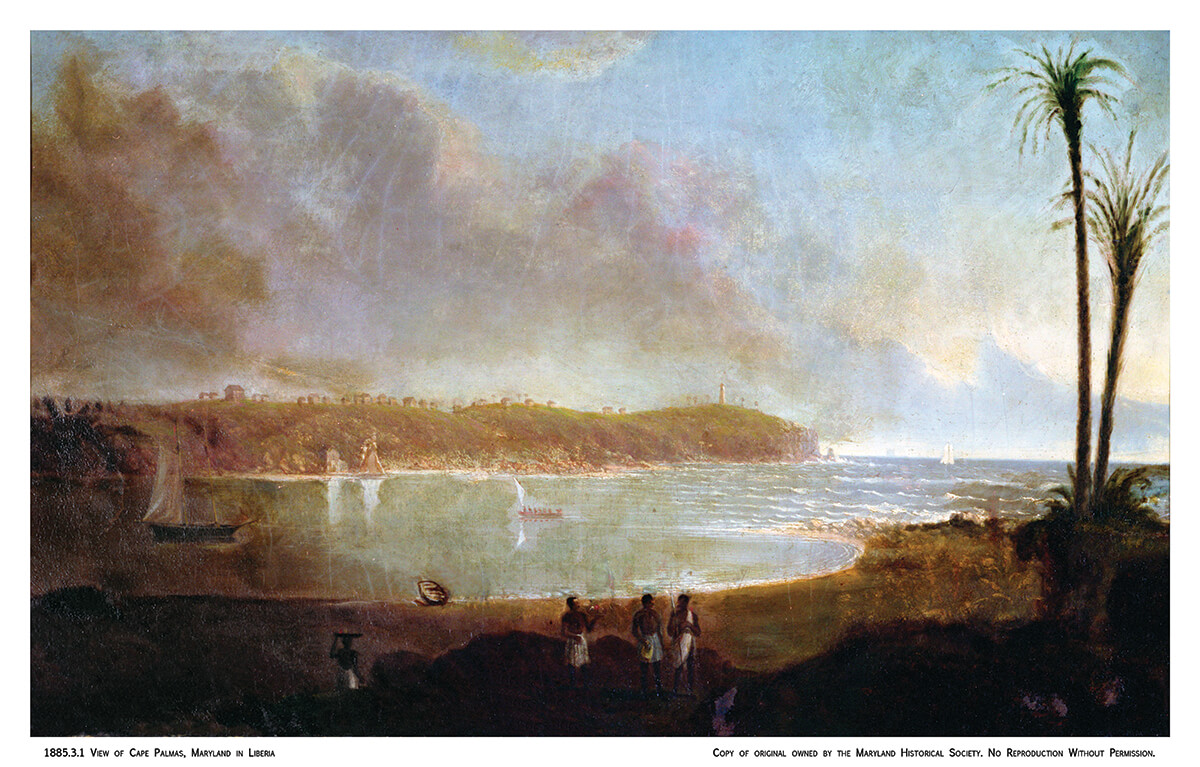

Four months after Turner’s uprising, the Maryland legislature allocated $10,000 annually for 26 years “for the transportation and removal of emigrants to Africa.” Maryland representatives subsequently purchased land from native peoples just south of the Liberian settlement in Cape Palmas.

The deportation effort struggled from the outset, however. In a report to the Maryland State Colonization Society’s board, one of the state’s traveling “recruitment” agents clearly summarized the reasons that African Americans overwhelmingly opposed colonization. They unyieldingly believed they were as entitled to the human rights set forth in the Declaration of Independence as all others born here.

“They [free Blacks] are taught to believe, and, do believe, that this is their country, their home. A Country and home, now wickedly withholden from them but which they will presently possess, own and control. Those who Emigrate to Liberia, are held up to the world, as the vilest and veriest traitors to their race, and especially so, towards their brethren in bonds. Every man woman and child who leaves this country for Africa is considered one taken from the strength of the colored population and by his departure, as protracting the time when the black man will by the strength of his own arm compell those who despise and oppress him, to acknowledge his rights, redress his wrongs, and restore the wages, long due and inniquitously withholden.”

From 1831 to 1851, only 1,025 emigrants—a fraction of manumitted African Americans in the state—were sent to Liberia. Colonization had been an issue upon which white supporters and opponents of slavery found common ground—as well as at least a handful of African Americans. Some of whom, it should also be remembered, persisted and thrived on foreign ground.

“I expect to give my life to bleeding, groaning, dark, benighted Africa,” Daniel Coker later wrote to Baltimorean Jeremiah Watts. Coker died in Freetown, Sierra Leone, in 1846, but not before founding the African Methodist Episcopal (A.M.E.) Church there and helping establish a lasting community. His descendants would become prominent citizens and leaders in Sierra Leone and Nigeria, where they remain to this day.

Decades after his death, his family would still recall their roots in Baltimore. In a letter from November 1891, West African A.M.E Bishop Henry McNeal Turner recalls a visit from two of Daniel Coker’s great-great granddaughters, 20-year-old Jane Coker and 11-year-old Susan Coker, describing them as “two beautiful ginger-cake-colored children, and very smart and bright.” He explained that they had “called upon me to inquire about their relatives in Baltimore.”

Jane Coker, Bishop Turner noted, worked as an interpreter for the missionary United Brethren of America among the native tribal population. “She wishes to visit Baltimore, but money is wanting,” Turner writes. “I told her if she dared to visit Baltimore…she would never get back; that the people would feast and honor her to death…”