News & Community

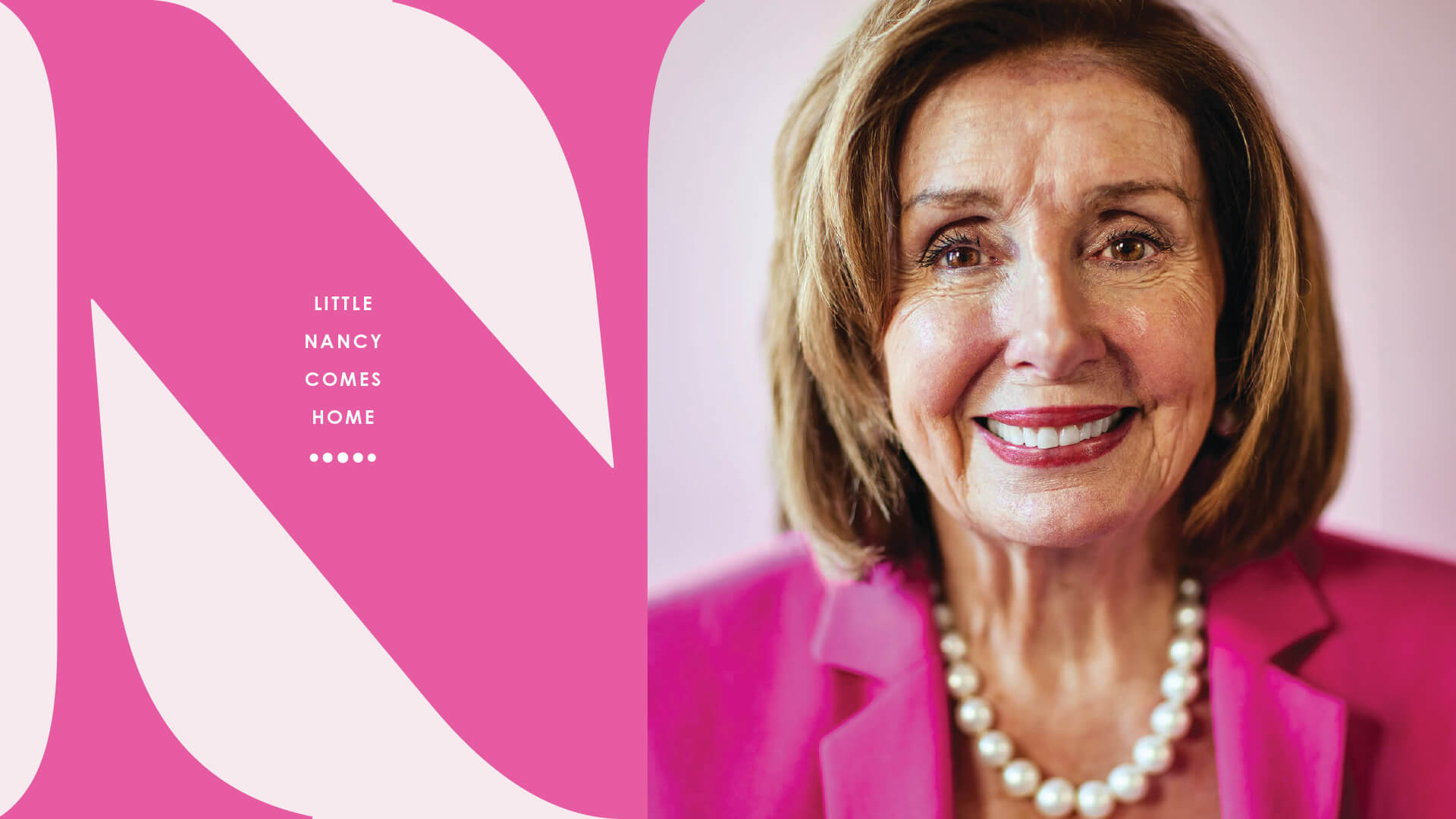

Little Nancy Comes Home

Little Italy’s hometown hero and the first female speaker of the House returns to reminisce about the place where she was born and raised.

By Jane Marion

Photography by Justin Tsucalas

N A PICTURE-PERFECT Baltimore day in mid-May, fueled by some combination of chocolate ice cream for breakfast, five or so hours of sleep, and a deep sense of duty, Nancy Pelosi holds court in a private dining room at Sabatino’s. This break at the Little Italy institution marks her third stop on a whirlwind official visit that includes at least five ports of call around Baltimore, the city where she was born and bred, a stone’s throw from her childhood family home—not to mention the place where both her father, Thomas Ludwig John D’Alesandro Jr. (“Tommy the Elder”), and her eldest brother, Thomas J. D’Alesandro III (“Young Tommy”), served as mayor.

But neither man is more famous than the congresswoman, arguably the most powerful woman in politics in all of U.S. history. After nearly two decades off and on, she stepped down from her position as speaker of the House last year and rejoined the rank-and-file as a member of Congress to her now-home state of California. Even at 84, the speaker emerita maintains an indefatigable, almost-superhero energy. The kind that should make her hometown proud.

Earlier in the week, she accepted the Presidential Medal of Freedom from President Biden for “her resolve on Jan. 6, 2021” and “her efforts to protect freedom and democracy.” In the weeks to come, the Lincoln Medal—given to the person who “exemplifies the lasting legacy and mettle of character” embodied by its namesake, the 16th U.S. president—will be conferred at Ford’s Theatre. She’s also been busy putting the finishing touches on her second memoir, The Art of Power: My Story as America’s First Woman Speaker of the House, due out this month, while gearing up to run for yet another term in November. And of course, she prioritizes spending family time with her husband, Paul, her five adult children—all born within a span of six years—and her 10 grandchildren.

“One of her sayings is ‘resting is rusting,’” says press secretary Ian Krager, who, at all of 24, is likely the only person who can keep up with her (though her entire entourage, including her communications and legislative directors, is exceedingly youthful). “I’m a workhorse, not a show horse,” is another one of her favorite sayings, he says. “There’s never a down day with her.”

Which brings us back to this day in Baltimore. After all, why do one thing in Charm City (like this interview) when you can do five? Her first stop of the day was to speak with Gov. Wes Moore at a Maryland Transportation Authority press conference, followed by a boat tour of the wreckage of the collapsed Francis Scott Key Bridge. After Sabatino’s, it’s off to Morgan State University (where she holds an honorary Doctor of Public Service degree), followed by a trip to the Social Security Administration with former Maryland Gov. Martin O’Malley, now SSA’s commissioner.

But for this brief moment, wearing her trademark uniform—a monochromatic hot pink suit over a simple white blouse and matching shoes, plus a chunky pearl choker—she’s picking at a plate of appetizers and a special salad and reminiscing about being back in the neighborhood where she spent those formative first 18 years of her life.

“Every time I come here, it feels like I just left 10 minutes ago,” says the speaker between bites of shrimp and bits of provolone scattered across her salad. “Growing up here was, of course, a family experience, but also cultural and religious,” she says of her Catholic upbringing. Her childhood memories—“too many to name,” she says—“are all centered around family and faith.”

Though many people assume she’s from San Francisco—her home away from home since 1969—there’s no denying she belongs to Baltimore, from her lingering accent and ramrod straight Institute of Notre Dame parochial-school posture to her trademark moxie and take-no-prisoners negotiating skills on full display in Congress.

“I am among the many Baltimoreans who are quick to claim Nancy Pelosi as a favorite daughter,” says Congressman John Sarbanes. “Her list of achievements is breathtaking. . . . And her success comes from never forgetting the lesson she learned from the Baltimore community that nurtured her: Power is only worth having if it is put to work for the benefit of others.”

In person, Pelosi is funnier, more diminutive (5’2” without her requisite three-inch heels), and more Italian grandmother-like than she comes across in the news. She eats everything on the table with her hands—from sausage and peppers to shrimp—then drips marinara on her shirt after dunking fried rings of calamari. (“I thought maybe I forgot to put out utensils,” says the server, laughing later.) But really, what’s a little red sauce when you’ve overseen the impeachment of an American president? Twice. “[Former U.S. Sen.] Barbara Boxer taught me that if you spill something on the front, you just turn it around,” says Pelosi, not missing a beat.

Somehow, a little sauce on a shirt—especially when it’s from the same 69-year-old recipe that the restaurant’s been serving since it opened its doors in 1955 (when a 15-year-old Pelosi lived down the street)—seems symbolic: In fact, her story can be traced in a trail of marina, where Italian-American pride and patriotism were central to shaping her. And sitting at the convivial “Sab’s,” beneath a portrait of Thomas Jefferson (“my hero,” she says), brings it all back. “We came here a lot,” recalls Pelosi. “Sabatino’s was hard to get into. It was always considered the haute cuisine of Italian food . . . but we went to all the restaurants in Little Italy,” she says, not wanting to pick a favorite, though this place carries so much of her family’s history within its walls.

Sabatino’s is where “Little Nancy,” as she used to be known, often ate with her parents and brood of brothers. It’s also where, once the kids were grown, “Tommy the Elder” and Nancy D’Alesandro—née Annunciata Lombardi, aka “Big Nancy”—sat most Monday nights at a round table by the window, from which they could look out and see their three-story brick rowhome. Sabatino’s is where a black-and-white photograph of Pelosi’s father, posing proudly outside the restaurant next to then-President Jimmy Carter, hangs in the hallway by the entrance downstairs, and where a life-sized mural—believed to include a relative on her maternal side, posing with original owner, Sabatino Luperini, among others—is emblazoned on the wall of a banquet room upstairs. And Sab’s is also where now-restaurant-owner Vince Culotta, who was friends with Pelosi’s older brothers, Hector and Nicky, fondly remembers delivering food to the family home when a widowed Big Nancy’s health was ailing.

While the rest of her family spent their lives in the city, Pelosi left for Washington, D.C., in 1958 to attend college at Trinity—the country’s first Catholic liberal arts college for women—never to move home again. And while it’s been some time since the speaker has been back in Baltimore, she returns, she says, “whenever I can,” and stays loyal to the neighborhood that nurtured her. Pelosi has a few relatives who still live nearby. And despite shuttling between San Francisco and D.C., she says, “We stay connected.”

“She’s a Baltimore person,” says Phil Culotta, Vince’s son, who has worked at the restaurant since 1973. “Her roots are here. She remembers us—and the neighborhood.”

DEPUTY EDITOR JANE MARION ENJOYS LUNCH WITH SPEAKER PELOSI AT SABATINO'S IN LITTLE ITALY.

ancy Patricia D’Alesandro was born on March 26, 1940, at the then-St. Joseph Hospital in Towson. She was the only girl in a family of five boys (a sixth died of pneumonia before Nancy’s birth). The future Beltway heavyweight came into the world weighing eight-and-a-half pounds, at a time when her father was still a U.S. representative in Congress, before becoming mayor.

Tommy the Elder’s political rise—from high-school dropout to local giant of the Democratic party—is a Horatio Alger story if ever there was one. The son of Italian immigrants, he was bitten by the political bug while attending the 1912 Democratic National Convention at the Fifth Regiment Amory on Division Street, the year Woodrow Wilson was nominated to the party. “My father was maybe eight or nine,” recalls Pelosi, “and his mother carried him on her shoulders so he could see. That was really exciting for him. I don’t know if it drew him to running himself, but it certainly awakened him to what it took. And so, when he was old enough to vote, he was running for office.”

The first family of Baltimore poses for a portrait in 1947 with “Little Nancy” front and center.—Courtesy of the Maryland Center for History and Culture

D’Alesandro, who entered politics in 1927, was a state delegate, a congressman, and, from 1947 to 1959, a legendary mayor of Charm City. To this day, his record of achievement—launching the Friendship International Airport (now the Baltimore-Washington International Thurgood Marshall Airport) and overseeing the groundbreaking of the Baltimore Harbor Tunnel and the Jones Falls Expressway—left an indelible mark on the city he served. Most memorably, he is known as the mayor who, after 50 years, brought back a Major League Baseball franchise (the Orioles).

But on a deeper level, for his fellow compatrioti in Little Italy, D’Alesandro’s contributions were more personal. At a time of intense discrimination, Baltimore’s first Italian-American mayor helped change attitudes about Italian immigrants.

“Tommy did more for the people and the neighborhood and the Italians than anybody in this country at the time,” says Vince Culotta. “I don’t think there were that many Italian congressmen in the ’30s and ’40s.” D’Alesandro’s oldest son, Young Tommy, went into politics, too, and became mayor, serving only a single term during the tumultuous 1968 riots that followed the assassination of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.

And then there was Little Nancy.

On the day of her birth, the Baltimore Guide newspaper presciently proclaimed, “We predict that this little lady will soon be a ‘Queen’ in her own right.”

Meanwhile, Big Nancy had different dreams for her only daughter. “My mother wanted me to be a nun,” says Pelosi, though, like most teenagers, she had her own ideas. “I thought I’d be a dancing queen,” she says, swiveling slightly in her chair for comic effect. “I was a ’50s teenager and I was madly in love with Elvis Presley—my girlfriends and I used to dance in our house on the first floor.”

Even at a young age, she was a bit of a trailblazer. “I wanted my independence right from the start,” she says. “I didn’t want people hovering over me. I wanted to go out and play and be with friends at the playground. I didn’t want anyone to go with me—I wanted to do my own thing.” She also knew that when it came time for college, she wanted to expand beyond the borders of Baltimore, a first for her family. “That was never a question,” she says matter-of-factly, though her father, who wanted her to attend college locally and live at home, took some convincing. “I was going to go anyway,” she says.

THE D’ALESANDRO FAMILY STANDING OUTSIDE THEIR HOME IN LITTLE ITALY. —Courtesy of the Maryland Center for History and Culture

Still, Little Italy was her world for 18 years. Her childhood home at 245 Albemarle Street on the corner of Fawn was decorated with Persian rugs, a piano, and an oil painting of the family. It was just down the block from her paternal grandparents (who lived at 235 Albemarle with 13 kids and rotating boarders, including an organ-grinder and his monkey in the basement), as well as her maternal grandparents (who lived at 204 Albemarle), plus her aunt (who lived at 314 Albemarle), with yet another aunt on nearby Eastern Avenue. Fittingly, in 2006, when she was incoming House speaker, the 200 block of Albemarle was christened Via Nancy D’Alesandro Pelosi.

“I don’t know that Little Italy looked that much different [back then],” she says. “Envision a place that is warm and friendly—Italian, in that respect—surrounded by delicious food and the smell of fresh-baked bread. . . . And people would say, ‘That person is Genovese, or that person is Milanese, or Neapolitan,’ so the whole map of Italy was represented here, from one family to the next.”

In those days, St. Leo the Great Roman Catholic Church was (and still is) at the heart of neighborhood. Everything that happened, from communions to weddings to funerals to post-election ravioli dinners, occurred at the place of worship on Exeter Street that was also central to Pelosi’s devoutly Catholic family’s life. “My parents didn’t raise me to be speaker, they raised me to be holy,” she says, noting with a touch of defiance that in May 2022, she was told by the Archbishop of San Francisco that, due to her abortion rights advocacy, she was “not to be admitted to Holy Communion.”

Although her brothers all attended St. Leo’s School, Big Nancy saw to it that her daughter would matriculate at her alma mater, the Institute of Notre Dame. “IND was important to me,” says Pelosi, who joined the debate team her freshman year. “I loved it there. I was a Latin scholar. The nun who taught us was my favorite teacher. She would always say, ‘You are classicists and are expected to behave in a certain way.’ And we were always like, ‘We just thought we were signing up for Latin, we didn’t know we were signing up to be a model to the rest of the class.’”

A BLACK-AND-WHITE PHOTOGRAPH OF PELOSI’S FATHER, POSING PROUDLY OUTSIDE SABATINO'S IN LITTLE ITALY NEXT TO THEN-PRESIDENT JIMMY CARTER, HANGS IN THE HALLWAY BY THE ENTRANCE DOWNSTAIRS.

Sen. Barbara Mikulski, who was a senior at IND when Pelosi was a freshman, recalls that the school’s standards were rigorous and the expectations high for the young women who enrolled. “You had to be brainy to go there,” says Mikulski, a legend in her own right as the longest-serving woman in Senate history. “We wore uniforms and, when you came to school, whether on a bus—or in the mayor’s limousine—we were all the same to the nuns.”

Of course, while academics were strong, there was an equal emphasis placed on faith, as well as community. “There was a strong commitment to love your neighbor and social justice and really advocating for the sick and feeding the hungry,” says Mikulski. “Your job was your neighbor—and everyone was your neighbor. We were taught to show up and stand up and speak up.”

Out of school, the future speaker enjoyed exploring beyond her tiny, tight-knit neighborhood that spread across roughly 15 square blocks. “The Enoch Pratt library was like a home away from home,” she says. “I’d go there several times a week. They had a wonderful children’s section, including books on Mahatma Gandhi, which was surprising for the ’50s.” She also enjoyed attending The Lyric. “The mayor had a box at the opera,” she says, “and we’d go on Wednesday nights, but I also went to children’s symphony on Saturdays.”

While her mother exposed the kids to the arts, the D’Alesandro men were passionate about sports. “I watched with them,” says Pelosi. “I didn’t want to be treated like a girl. I knew every fight song of all the teams,” she says. “We were always at the games. Sports were a unifying thing in a family with a lot of boys; we watched them all the time.” To this day, she’s a serious fan—though perhaps sacrilegiously for a certain sector of Baltimore. “The Orioles are my second team, after the Giants,” she says, “and the Ravens are my second team, after the 49ers.”

Family dinners on Albemarle were also seen as something sacred. “That was the center of our existence,” says Pelosi. Her father often had commitments in the evening, but in true Italian fashion, he still prioritized the ritual of coming together over a meal. “He’d come home from City Hall and we’d have an early dinner together and then he’d change into black tie and attend three or four events,” she says.

Beyond the dinner table, the D’Alesandros did everything as a unit.

“People would say, ‘Don’t ever invite Tommy D’Alesandro to something unless you want the six kids who come with him,’” she recalls. “We were always moving as a pack.”

Though her mother, who died in 1995, never worked in politics formally, she was a devoted and fastidious organizer who pulled Little Italy’s women into her husband’s grassroots campaign, all while raising her children. (In her Sun obituary, Young Tommy called her “the true politician of the family.”) She had wanted to be a lawyer, but that wasn’t in the cards. So instead, like many women of her generation, Big Nancy operated behind the scenes. She knew, for example, that the best political assets were women. “She instilled in all of us that the VIPS were the ‘volunteers in politics’—the people who did the grassroots organizing,” says Pelosi. And just by being in her family, that meant the D’Alesandro women, too.

“There was never any election that we weren’t giving out buttons or leaflets or placards,” she says. “We lived in a very Democratic neighborhood—maybe there was one time when two votes went Republican, and it was like, who could it be?”

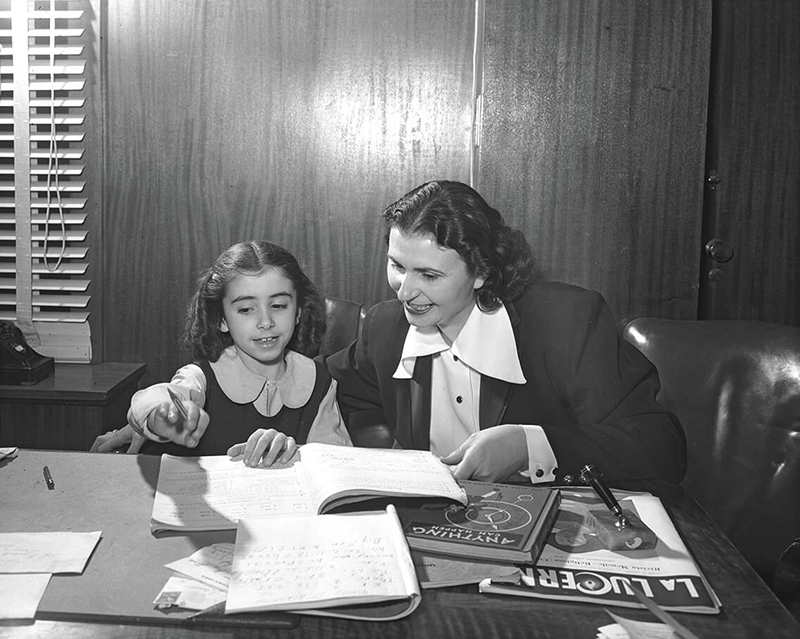

Big Nancy also ran an ad-hoc community help desk known as “the Favor File.” Constituents seeking advice or aid would line up outside the house and around the corner on Albemarle, then stream in one by one to talk to Big Nancy. In her early teens, Little Nancy, already an astute political observer, sometimes sat by her side, ready to take notes that would later be typed on index cards and filed away.

BIG NANCY READING WITH LITTLE NANCY, DECEMBER 1947.—Courtesy of the Maryland Center for History and Culture

“Because I listened to my mother, I knew how to tell people how to get on welfare, how to get a place in the projects, or a bed in a city hospital,” she says. “In seventh or eighth grade, I came home and played, but if [a need] came up, then that’s what I did.”

“She learned a lot from her mother,” confirms Mikulski. “Her mother really handled a lot of the constituent service when people called the home. And even when her father became ‘the bigshot,’ they stayed in Little Italy.”

Big Nancy also forged connections farther afield, including with local women’s groups in Greektown, Polishtown, and other urban villages. From watching that, too, “Nancy knew how to make strong communal times,” continues Mikulski. “She had community grassroots down. She knew how to do the macro—and the macaroni and cheese. Nancy always remembered where she came from—that helps you remember where you want to be.”

Of course, every favor was a potential volunteer or vote for her father when it came time for the polls, though Pelosi says that was never the motivation. “It was more about paying it forward,” she says.

“They helped a lot of people,” recalls Vince Culotta. “I don’t remember them ever turning anyone down. If you needed something, they’d say, ‘Go see Tommy or Miss Nancy,’ because she would get through to him. If you needed a job or a street sign or something taken care of, they would help you.”

That early education in politics served Pelosi well when she ran for office many decades later. “I would observe [them] before an election, getting out the yellow legal pads and saying, ‘These are the votes we need—now how many are we going to get from this neighborhood and how many from that neighborhood?’ To win, you had to know how to count, and when I say that, I mean you had to know the reality of the count—build in a fudge factor but understand that you have to get out your vote.” This became something of a political trademark for Speaker Pelosi. She would never bring a vote to the House floor if she didn’t know she had the necessary count to win.

Even the week before this visit to Baltimore, Pelosi met with candidates for the Democratic primaries, telling them, ‘You have to own the ground—all the rest of it is a conversation, whether it’s social media, whether it’s mail or TV,’” she says. “Whatever it is, you must do that messaging to inspire, but it’s all a conversation unless you own the ground. You must know how many votes you need, where you’re going to get them, and make sure you have them—that’s what I saw my father do and that’s what I did to win for office, too.”

She still remembers her first trip to D.C., when she was six years old and her father was getting sworn into the House for his last term in Congress before running for mayor. “We all piled into the car and as we got closer, my brothers are like, ‘Nancy, Nancy, there’s the Capitol.’ I said nothing. Then a little bit later, ‘Nancy, Nancy, there’s the Capitol.’ By the third time, I said, ‘Is it a capital A, B, or C? I don’t see any capitals.’” “They said, ‘It’s the dome of the Capitol, Nancy,’” she recounts, clearly delighting in the punch line. “And there it was, this beautiful Capitol, and to see it is something very moving. . . . The excitement they had is still something I carry with me.”

Which is one of the many reasons why she’s so heartbroken when she reflects on January 6. The events of that day—and the subsequent vicious home attack on her husband, Paul—remain raw for Pelosi, who avoids even so much as saying former President Trump’s name (she refers to him using various adjectives, such as “grotesque”). And she calls that fateful day as she sees it: “It was an insurrection incited by the president of the United States.

“To see these vile creatures incentivized by the most vile creature of all degrading the Capitol was terrible,” she says of the day. “But what was more terrible is that they were undermining the Constitution and undermining Congress’ responsibility that day, as well as defecating in the Capitol.”

SABATINO'S IN LITTLE ITALY.

At this fulcrum point, she doesn’t see retirement as an option.

“My mission right now is to make sure that the Democrats save our democracy for what could be on the horizon,” she says. “That is my mission; I am usually on a mission rather than a schedule,” she adds, spouting another one of her Pelosi-isms. “Over the years, when someone won or someone lost, you would just move on, but this election is Washington crossing the Delaware. We must win, or else I don’t know that our country can withstand.”

As numerous staff members give the signal that it’s time to go, the speaker continues to talk with some urgency about the upcoming presidential election, even as she poses for a photo with the young Sab’s server, whose mom is a fan. “The national anthem was written in Baltimore,” she says. “My favorite line is, ‘proof through the night that our flag was still there’—that’s what this election is for us. We must prove through the night to what’s-his-name that our flag is still there.”

Pelosi points out that Little Italy is an immigrant community where “patriotism is a strong sentiment and people have chosen to be here.” That’s the America she is proud of. That’s the America she wants to preserve.

Soon, she’s descending the steep staircase with a phalanx of people from her security detail. She walks through the front doors and outside of Sabatino’s, then poses for a portrait in her turned-around top. Afterward, she hops into the back seat of a black Suburban, buffered by a motorcade of Baltimore City police officers, ready to escort her to the next stop. Her press secretary carries a brown paper bag with her to-go pasta order—penne with mushrooms, peas, carrots, veal.

And house-made red sauce, of course.