Ross Jones spent decades at Johns Hopkins University without ever learning the story of the university’s first president’s extraordinary daughter Elisabeth Gilman. A rebel in her time, Gilman traveled the country and the world advocating for those whose voices were not as easily heard as her own. She fed and entertained U.S. servicemen in World War I France, provided relief for miners and their families throughout Appalachia, called for an anti-lynching law in Maryland, and ran for several offices as a member of the Socialist Party, among other things.

Though her story was mostly lost to time, Jones has revived this 20th-century heroine in his new book, Elisabeth Gilman: Crusader for Justice. Ahead of his book talk and signing at Evergreen Museum & Library November 1, we spoke with Jones about gathering the details of Gilman’s past and what she might think about the state of the present.

How did you first come across Elisabeth Gilman’s story?

I was doing research, and this is probably 10 years ago, in the Eisenhower Library in the archives. I noticed a her name in a file and, to tell you the truth, I did not know she existed. I didn’t know that Daniel Coit Gilman had a daughter—he actually had two. It turns out that she had donated to the Hopkins Library in the 1940s all of her letters, diaries, scrapbooks, and pictures. She even did an informal memoir that was in there, and I spent about an hour or so just sort of leafing through things. I quickly came to the conclusion that this was really fascinating and it might be worth a story. So then I went back on a number of occasions just in the early days and went through the whole file and was able to read everything.

Tell me a bit about the research process. After that first file, where do you go from there?

I concentrated on her letters first. There were many of them and she, fortunately for me, wrote in a nice hand. Most of the letters were written from during World War I and to her sister. She had gone over as a volunteer with the YMCA, which ran a canteen in Paris for soldiers coming off the front for rest and recreation. And she was in a hotel that was taken over by the military, 450 residents whenever the soldiers were there, and she would provide food and entertainment, and she wasn’t alone. There were several women who did that. She was there for about two years and she wrote letters to her sister two or three times a week. And so you got this picture of what life was like in Paris during the war, what she was up to, entertaining the troops, and some of the things that were happening to her. Her enthusiasm for her job was very, very touching.

That habit of letter writing has really gone by the wayside. It’s a shame people won’t have those kids of materials for research in the future.

It’s really a lost art in many ways, and I don’t know what we’re going to do now that we just have everything online, you know. There’s no original materials anymore. One of the things that really fascinated me was Elisabeth, in the winter of 1917, had to buy an overcoat, and she wanted to tell her sister. She wrote to her sister about it and she cut a little swatch of the material, a kind of blue and black wool, and pinned it to the letter. Well, it’s still there. That really amazed me, over 100 years old now and still has its colors.

Gilman was quite the radical in her time. Can you talk a little about how she came to be that way?

I would characterize her as being the centerpiece for social reform and social justice in Baltimore for the first half of the 20th century. She was into so many things. She started out as a social worker. In 1916 she went up to Boston and heard a professor from Wellesley who was an Episcopalian, like Elisabeth was, and also was a socialist and it a Elisabeth’s introduction to socialism. She came back to Baltimore and, lo and behold, almost as soon as she got home, she had an invitation to go to an international socialist rally. It was a weeklong rally held in, of all places, Sherwood Forest. It’s hard for me to believe that anything like that would be held there!

Anyhow, she met a radical Episcopal priest named Mercer Green Johnston. He had just been dismissed from his church in Newark, New Jersey, because he was too radical. They were birds of a feather and a kind of reinforced each other’s idealism and interest in socialism. And then the war came along. Johnston signed up to go drive an ambulance in France, his wife went over as a volunteer for what was called the National Surgical Bandage, Committee, and they asked Elisabeth to go with them.

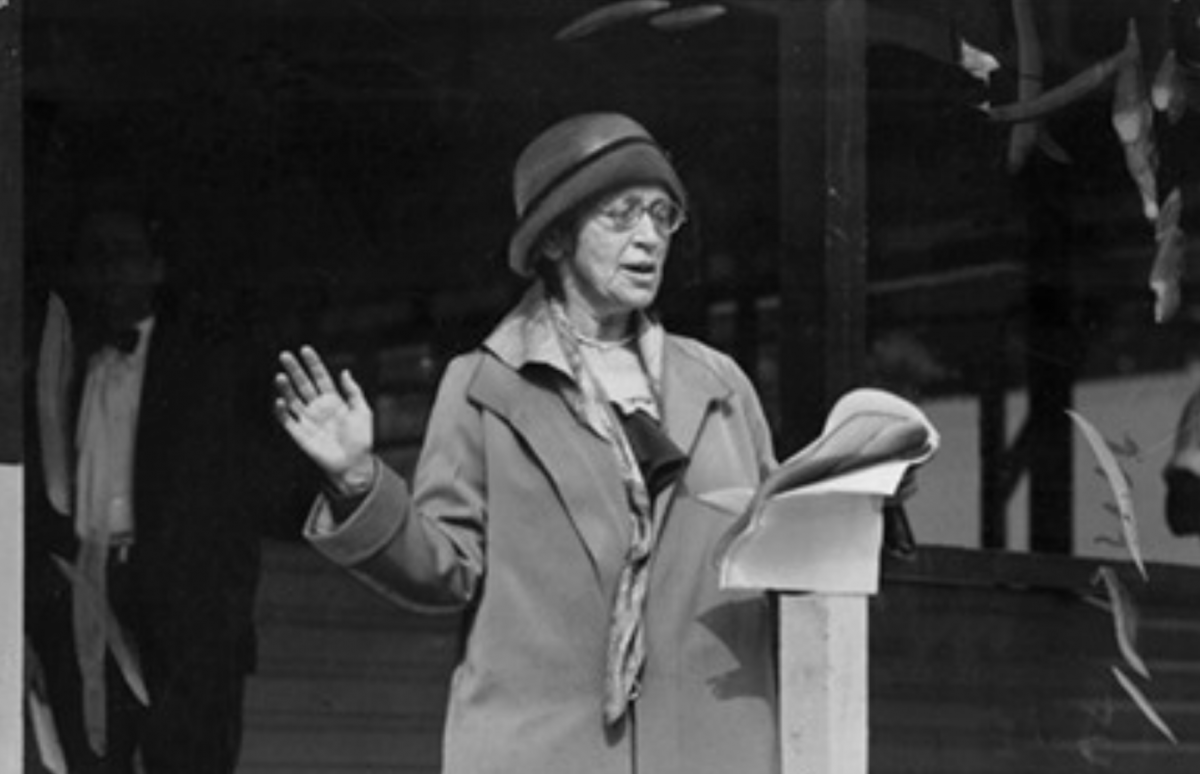

She came back in 1919 and then she really got revved up doing all kinds of activities. She was the secretary of the West Virginia Miners Relief Association, she went to Washington, D.C., to testify at a meeting of the House Immigration and Naturalization Committee, she held a meeting at her home in 1931 a where the Maryland chapter of the American Civil Liberties Union was founded. She was nominated for governor in 1930 by the Socialist Party and lost by huge, huge margin. But she used the platform to talk about her liberal views, and her message was that the Socialist Party wants to make the world a better place for everyone to live. She said that over and over again. She ran twice for the United States Senate. She ran for mayor of Baltimore, even sheriff. So she really was a pistol. When she wasn’t running, she was doing things like badgering Congress for relief funds for workers during the depression and she was always speaking out against racial discrimination.

The word socialism can sort of scare people off sometimes. Can you tell me a little bit more about sort of what the concept meant to her?

Well, the concept meant to her that the government would own major industries. Many of the things that she was pushing for prior to FDR’s election were actually put in place by his administration. I think she was a kind of a quiet socialist in the sense that she wasn’t super radical. She just saw and felt that the working people of the country, men and women and their children, weren’t getting a fair shake. She pushed for cheaper trolley fairs in Baltimore. She wanted to lower gas rates, electric rates, and water charges. She was fighting against a big business that she felt was taking advantage of working class people.

Where do you think Elisabeth would fit into today’s world?

She would be having a ball today. Everything going right now is just the opposite from what she believed in, what she fought for for all those years. I think she might be a little sad to come back and see some of the things that are happening today. Voices like hers need to be heard, and I think they are being heard more and more. She might be a little disappointed that racial relations are not as positive as she might’ve hoped. For her to have fought it for that then and to realize that that the racial discrimination, the issues with the police and African-American men, and other things that are going on today I think would have disappointed her very greatly.

How do you hope people remember her?

I would always hope that people would read the book, and then maybe if anyone should ask them today who Elisabeth Gilman was, they would tell you what a champion she was for liberal causes and how dedicated she was to the advancement of social justice and the well-being and working people in her day.