History & Politics

After 45 Years, SCOTUS Sketch Artist Art Lien Sets Down His Pencils and Watercolors

The Supreme Court is one place cameras are still not allowed.

Art Lien botched his first courtroom assignment. He had graduated from the Maryland Institute College of Art in 1976—“painting houses and freaking out about what to do with my life”—when he learned WJZ-TV needed a sketch artist to cover Gov. Marvin Mandel’s corruption trial.

He went to the newsroom, drew a few people working at their desks, got sent to a pre-trial Mandel hearing, and was promptly fired after his watercolors ran all over the non-absorbent paper he’d brought.

Desperate to redeem himself, he explained his blunder (the paper worked in the studio but not the courtroom) and offered to tackle another assignment for free. That turned out to be the trial for the killing of Councilman Dominic Leone at City Hall, whose murderer, with the help of soon-to-be legendary Baltimore defense attorney Billy Murphy, was found not guilty by reason of insanity.

Courtroom illustration is a dying art, with cameras generally allowed in courtrooms, but the tumultuous ’70s proved the perfect time to break into the niche profession. The Judicial Conference of the United States had formally prohibited cameras from courtrooms while Lien was at MICA.

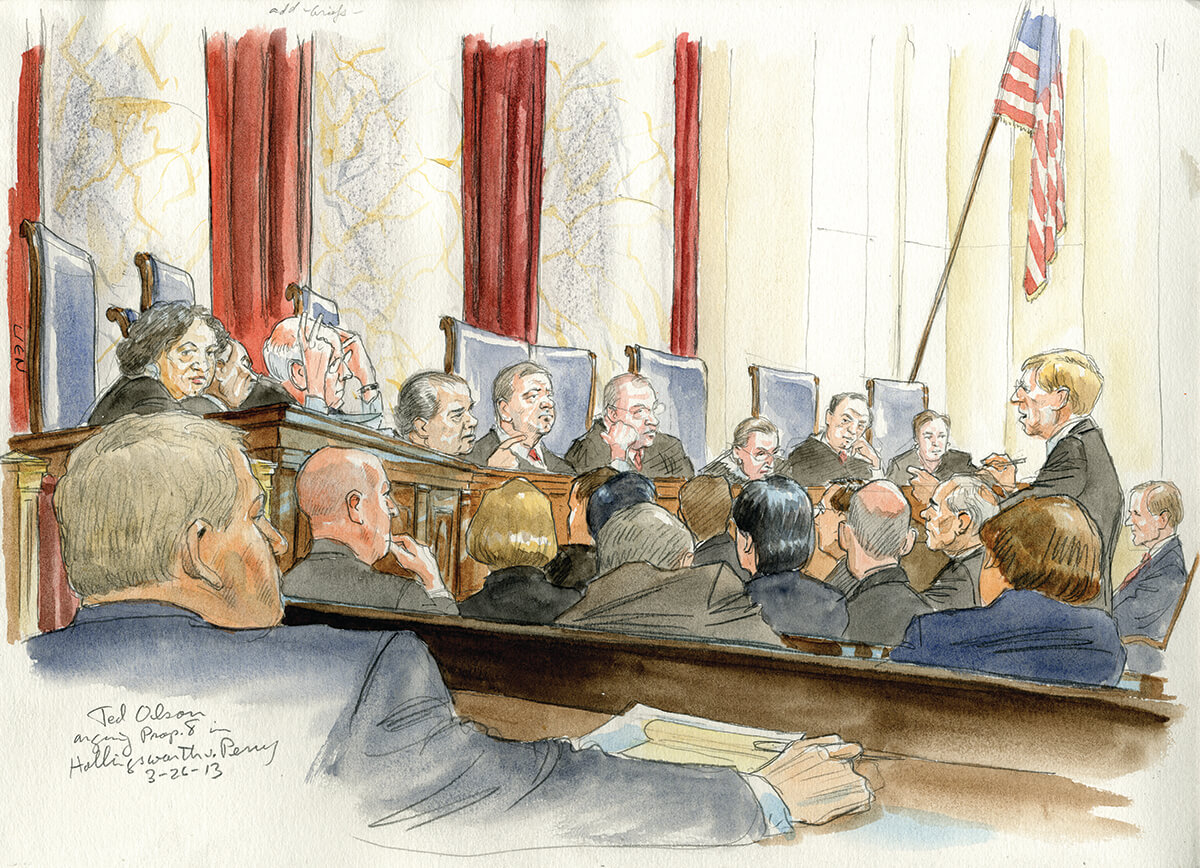

“I fell into it,” says Lien, who lives in Catonsville and retired this spring after going on to cover the Supreme Court and the nation’s most historic cases for more than 40 years, including the court’s overturning of California’s gay marriage ban in 2013, pictured above.

“After those first trials, I wrote letters to the three networks. At CBS, Howard Brody, who’d covered World War II and everything since [including the trial of the Chicago 7 and the Watergate hearings], I guess he was getting tired of doing it, and I tried out. Howard was wonderful. He took me to the Supreme Court and the Senate.”

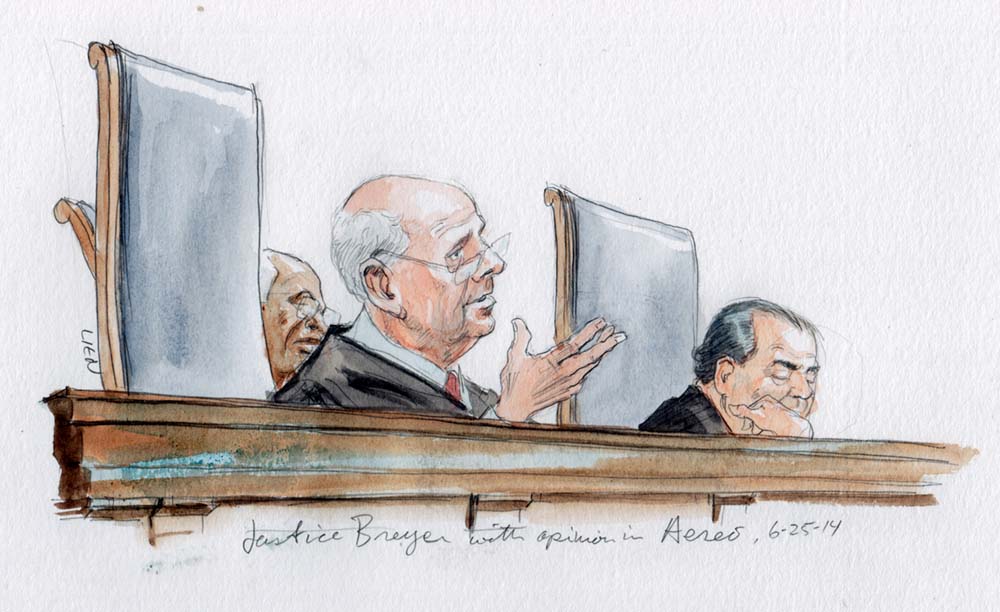

The Supreme Court is one place cameras are still not allowed. In the early days, Lien occasionally spotted justices having breakfast in the court’s dining hall.

“You’d see Harry Blackmun there, who wrote the Roe v. Wade decision,” Lien recalls, referencing the landmark decision that was just overturned. “There was no metal detector and security was relaxed. Today, there’s a fence around the entire building. A different time in every way. John Paul Stevens was a junior justice when I started and one of the more conservative justices. By the time he retired in 2010, he was one of most liberal justices.”

Lien obviously had a unique front row seat to history, but remains modest about his career. His mother, he maintains, was the real journalism star in the family.

“She was a groundbreaking international economics reporter and wrote a column for Le Monde in Paris under a pseudonym,” he says. “She was way more interesting than me.”

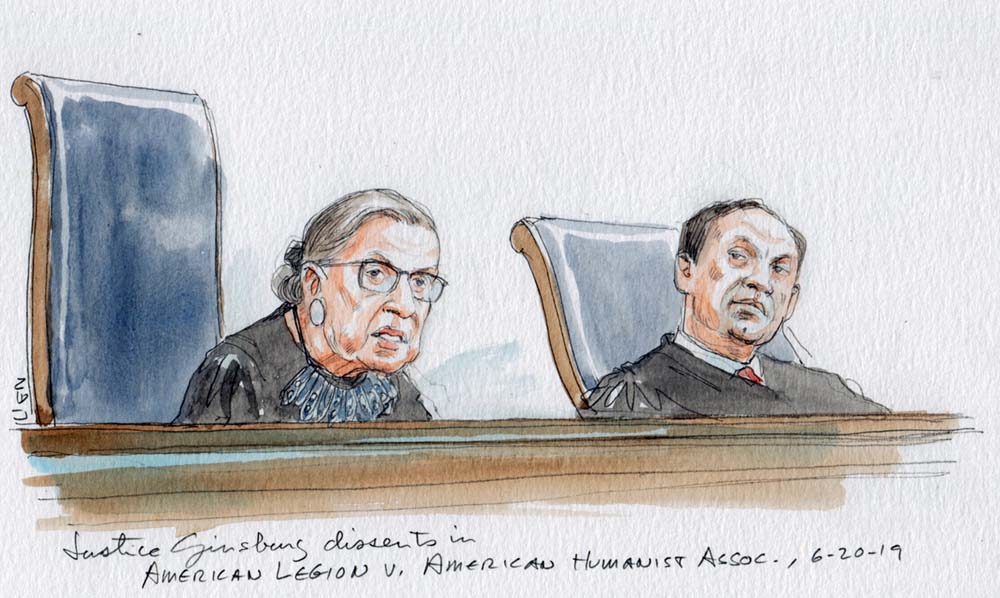

For the most part, his interactions with the justices were limited to observing them query lawyers during cases. Baltimore’s renowned Justice Thurgood Marshall, for example, in step with his irascible reputation, did not suffer fools and could get testy in court. Lien also remembers Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg, who was still driving herself to work at the time, coming to the press room and complaining about D.C. drivers.

Former Justice William Brennan, the son of Irish immigrants, approached Lien directly once—during a gallery showing of the court’s sketch artists’ work. “He’s looking at my sketch, and I’m next to him, and he said, ‘You made me look like a leprechaun.’ The funny thing is, he was short and you only saw his head peering over the bench and he did kind of look like a leprechaun.”

The most indelible trials Lien covered were not in the Supreme Court, however, but in Oklahoma City after the Timothy McVeigh bombing, in Boston after the marathon bombing, and in Texas following the gruesome, racist murder of James Byrd Jr., who was dragged to his death behind a pickup truck by three white men in 1998. “The testimony of the survivors and families is really hard,” says Lien, who also covered the trials of the police officers who were charged in the death of Freddie Gray.

Ultimately, after working remotely during COVID, Lien realized he didn’t want to commute to Washington anymore. At the moment, he has no plans to pull together a book of illustrations or start any new art projects. Recently, he even turned down a commission from the clerks of Justice Amy Coney Barrett. Instead, he’s looking forward to restoring a couple of vintage Holdsworth and Raleigh bicycles in his garage.

“After 45 years,” he says, with a happy but weary chuckle, “I don’t want to draw right now.”