Senator Barb

How did the daughter of Polish grocers become dean of the U.S. Senate women?

Look at the first half-dozen times Sen. Barbara Mikulski’s name appears in The Sun and you can learn almost everything you need to know about her. It’s all before she ever ran for an elected office.

In 1962, a Mount St. Agnes College alumnae reunion announcement mentions that a “Miss Barbara Mikulski” will be assisting in organizing the event. It’s exactly the type of unglamorous assignment that a go-getting, 25-year-old woman signs on for: a ton of phone calls and errands, and lots of networking possibilities. Two and a half years later, “Miss Barbara Mikulski” appears again in The Sun, this time as a National Institute of Mental Health-granted social worker providing testimony at City Hall on behalf of an anti-poverty bill put forward by then City Councilman William Donald Schaefer.

By 1967, the daughter of Polish corner grocers has risen to assistant chief of community relations at the city’s Department of Social Services. She’s also in charge of a new city program providing a housing subsidy that—at an average of $15 to $25—isn’t much of a subsidy at all, she notes in one story. A year later, in the aftermath of the 1968 riots, she’s highlighted among those teaching a class for a Johns Hopkins University “Freedom School” initiative.

The feisty, tell-it-like-it-is Barbara Mikulski that Baltimoreans have come to know, respect, occasionally fear, and often love? She first emerges in 1969—at least in print. (She’s always joked that she considered becoming a nun before realizing, with the help of the sisters at the all-girls Institute of Notre Dame high school, that the “obedience” requirement might be a personal obstacle.) Still at her social services community relations position, Mikulski publicly calls out her own agency for allowing 55,000 city children to suffer from malnutrition.

The Sun characterized Mikulski and a welfare recipient who spoke up during the community meeting as taking “a healthy bite on the hand that feeds them.”

The ambition, smarts, spunk, leadership, commitment to social justice, interest in bridging racial divides—the understanding that the ability to create fundamental change lies among those with political power—it’s all taking shape. And the colorful personality—the self-effacing humor, the crackling quips, the bold strategic action—that’s about to come into view, too. In August of 1969, as her beloved Orioles are dominating the American League, Mikulski appears in the paper of record in the fight that will soon make her a rowhouse-hold name.

In a story headlined “Expressway Opponents Vilify Officials,” a 33-year-old Mikulski goes after a 16-lane urban highway scheduled to cut through the heart of the city—her city, where she has lived her entire life—from West Baltimore to the Inner Harbor, Fells Point, Canton, and Highlandtown. At a coalition gathering with West Baltimore residents, Mikulski takes a poke at city and state leaders’ promises of future development when, she snaps, “We haven’t even had present-day development.” She was just getting started.

The Fells Point Fun Fest in the fall of ’69 drew 50,000 people to the base of Broadway for steamed crabs, raw oysters, Polish sausage, beer, live music, tugboats, and ethnic folk dancers. The third annual event attracted local politicos, including former Mayor Theodore McKeldin, Del. Julian Lapides, and Schaefer—who had become City Council president, as well as a strong proponent of the East-West Expressway, which was projected to raze a couple hundred of Southeast Baltimore’s historic homes.

The Sun reporter assigned to the event noted that throughout the otherwise festive carnival atmosphere, a protest group identifying itself as Radio Free Fells Point had blasted “SOS” messages condemning the city’s Urban Design Concept Team, which it derided as the Urban Design “Concrete” Team.

One member of Radio Free Fells Point, the reporter quoted in the last line of the story, shouted her opposition as Schaefer tried to speak. “The British couldn’t take Fells Point, the termites couldn’t take Fells Point,” the protestor railed. “And we don’t think the State Roads Commission can take Fells Point either.”

Could there be any doubt who those words belonged to?

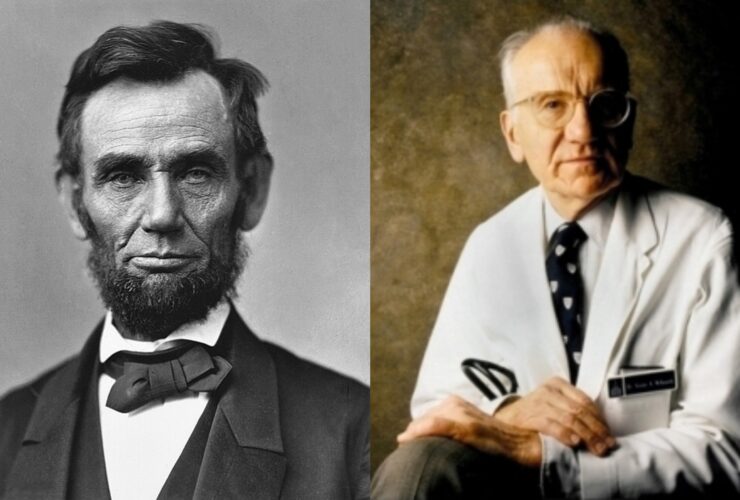

Then Rep. Mikulski in 1978 explaining legislation to help battered women. —Getty Images

When Barbara Mikulski won election to the U.S. Senate in 1986, there had never been another Democratic woman elected to the upper house of Congress who wasn’t appointed or succeeding a deceased husband. Her entrance into the quintessential “boys club” after a decade in the House of Representatives also distinguished her as the first Democratic woman to serve in both chambers. And by the time Barack Obama presented Mikulski with the Presidential Medal of Freedom last November, she had become the longest-serving female member of Congress ever.

But to view the scope of Mikulski’s career only in terms of “first” and “longest” would be to miss her undeniable legislative achievements—from groundbreaking funding for lifesaving women’s health research to support for the Baltimore-based Hubble telescope institute. When Obama presented Mikulski with the nation’s highest civilian honor, he described her as a “lioness” on Capitol Hill, noting she’d authored the first legislation he chose to sign into law—the Lilly Ledbetter Fair Pay Act. It would also diminish her trailblazing role in changing the culture and fabric of the Senate, where, for example, the gym had remained “men’s only”—because some of the old male guard didn’t want to give up the privilege of swimming in the nude—and tradition required that women wear dresses or skirts on the Senate floor, leading to her celebrated “Pantsuit Rebellion” of 1993.

“I had Grown Up in an urban village, a kind of European ethnic mayberry,” Mikulski says.

In March of last year, of course, Mikulski announced at Henderson’s Wharf in Fells Point that she would not seek reelection. Although she’s now 80, the news still came as something of a minor shock. She remains healthy and vigorous, and she is the state’s most popular elected official, according to polls. By all indications, she would’ve handily won office again. The cobblestone street where she delivered her announcement could not have been a more fitting location. She noted it was not far from where her immigrant grandmother opened a bakery, where her parents ran a small grocery—and just a few short blocks from where she launched her political career.

“It’s where I learned that we are all in this together,” Mikulski said at the press conference, choking up briefly when speaking about her staff, upon which she is famously tough, and her close working relationship with fellow Maryland Sen. Ben Cardin. “And it’s where I learned about service from my mother and father, who said, ‘Good morning, can I help you?’ every morning when they opened the small neighborhood grocery they owned and ran.”

She had concluded, she explained, in her direct style that has lost little of its fire after four decades in Congress, that she didn’t want to spend the next two years trying to finance another campaign run. Not when so much work remains to be done.

“Do I spend my time raising money or raising hell to meet your day-to-day needs?”

At a reception after her 1987 Senate swearing-in ceremony. —Getty Images

In hindsight, the grievances over swimming pools and pantsuits may seem minor and merely symbolic, but the casual, bipartisan chauvinism they reflected were significant to Mikulski and the women legislators of the era, who were regularly treated as second-class citizens on Capitol Hill.

“When Barbara decided to run in Maryland’s Democratic Senate primary, I can tell you, the attitude was, ‘Why is she running when there is a good guy? Women should only run if the other person isn’t good,’” recalls former Colorado Rep. Patricia Schroeder. “In this case, the good guy was Mike Barnes, a congressman from Montgomery County.”

Schroeder notes that while women were only a tiny percentage in the House—4.1 percent in 1977 when she and Mikulski first served together—at least there were 17 others. When Mikulski entered the Senate, there was only one other woman, Nancy Kassebaum, a Republican. “Even compared to the House, the Senate was a different world,” Schroeder says, almost chuckling at the institution’s ingrained sexism. “It was like Mad Men. When some of the female members of the House became appalled at the attacks on Anita Hill, who, of course, was testifying in front of an all-male, all-white judiciary committee [alleging sexual harassment against then Supreme Court nominee Clarence Thomas], we realized at one point the Senate wasn’t in committee but normal caucus. So, we over went there to discuss it with them. And you know what they said at the door? That they didn’t let strangers in.”

Eventually, several senators agreed to discuss the matter, she continues. “You know what Joe Biden [the judiciary chairman] says? He’d already talked about Thomas’s nomination with Sen. [John] Danforth in the gym and he’d promised they wouldn’t drag out the hearings. At the gym.”

“I’m not much of a jock anyway, but they just couldn’t accommodate me and that’s where they networked,” says Mikulski in her Senate “hideaway” office inside the U.S. Capitol, sitting at her parents’ old dinner table from their Highlandtown home, a table she had refinished. Mementos of Baltimore and photos of Mikulski with Girl Scout troops sit on the same shelves as pictures with presidents, world leaders, and female congressional leaders past and present. “That’s where they bonded.”

It’s worth remembering that Mikulski had been the first candidate endorsed by the newly formed, women’s pro-choice political action committee EMILY’s List in 1986—in the midst of the Reagan Revolution. “She was the first member of Congress I’d ever met,” says EMILY’s List founder Ellen Malcolm, who admits to having been both awed and slightly intimidated by Mikulski’s no-nonsense, full-speed-ahead approach during that initial one-on-one. “We had $5,000 and I told her I thought we could raise between $50,000 and $100,000 for her. She took out pencil and paper and said she was putting me down for $100,000. I thought I’d better do it.”

Mikulski remained the only Democratic woman in the Senate for her first six years until the image of Hill in 1991 getting grilled by the all-male judiciary

committee sparked something of an uprising the following year with the elections of Patty Murray, Carol Moseley Braun, Dianne Feinstein, and Barbara Boxer.

Headline writers hailed it “The Year of the Woman.” Mikulski responded in classic contrarian fashion: “Calling 1992 the Year of the Woman makes it sound

like the Year of the Caribou or the Year of the Asparagus. We’re not a fad, a fancy, or a year.”

With Sen. Paul Sarbanes. —Photography by David Colwell

By that time, with assistance from Maryland Sen. Paul Sarbanes, Mikulski had earned several key committee assignments, and had set a successful example. She showed her new female colleagues the ropes. Specifically, she crafted “Power Workshops” for rookie women senators, whom she implored to “suit up, square your shoulders, put your lipstick on” and fight. Later, with Texas Republican Sen. Kay Bailey Hutchison, she launched bipartisan, monthly women’s dinners, which have continued—out of the public eye—for more than two decades. “There’s only one rule, which still holds,” Mikulski says. “No staff, no memos, and no leaks.”

“I had not wanted to be the first and only,” she continues. “I wanted to be the first of many.”

“It was a big deal when Barbara Mikulski was elected,” says Susan Carroll, senior scholar at the Center for American Women and Politics. “After the hope of the 1970s, the ERA [Equal Rights Amendment] had petered out. There had been great enthusiasm around Geraldine Ferraro’s vice presidential nomination, but it turned to apprehension in the mainstream when that ticket fared so poorly. Then, Barbara Mikulski won and she immediately started getting a lot of attention in the national media. The narrative started to shift again.

“What stands out for me most is the way that she created space for other women in the Senate,” Carroll adds. “She socialized with them, brought them under her wing, and built a sisterhood, which now includes 20 Senate women.”

The former Catholic schoolgirl turned social worker certainly didn’t set out to become a feminist icon. Her entire career, Mikulski says, has been unplanned.

“Each step,” she explains, “was an evolutionary step that I didn’t know I was going to take. A lot of young people want to check this box and check that box, and I don’t believe in that. You want to have a goal, but you don’t always know what the next step is or should be.”

Mikulski’s goal was service, informed the old-fashioned way by family, faith, and community, and she started at Catholic Charities, working with foster care children and children in group homes. She learned a great deal—mostly that she wanted to stop families from breaking apart—and then more during her two years working in city social services. “Those two years were very determinative in my life. I had grown up in an urban village, a kind of European ethnic Mayberry,” she says. “And I saw situations that could be dangerous, a risk, for children. It wasn’t all related to physical abuse. It was often the poverty and corrosive effects of the poverty that led to a kid’s truancy and other problems. I decided to go to graduate school to help change the system.”

“People were being bulldozed out of their homes and they were being treated like a commodity. . . . ”

While Mikulski had few female political leaders to look up to as a young woman, there was no shortage of female role models in her tight-knit Polish community. She was a Brownie and then a Girl Scout growing up. She was inspired by the intelligence and strength of the Institute of Notre Dame nuns who taught both her and, coincidentally, Nancy Pelosi, who arrived at the school a few years later and would go on to become Speaker of the House. Long before she met Gloria Steinem in the late 1970s, she met Notre Dame’s Sister Francis Regis Carton, who held a doctorate and taught history. Naturally, she was also influenced by her grandmother who started the family’s bakery, as well as her mother, Christine, who managed the grocery store and was known as the “First Lady of Highlandtown” because of her civic activities.

Mikulski, who never married or had children, found her calling in politics—which she describes as “social work with power.”

For a time she intended to pursue a doctorate, possibly in public health or public policy, on top of the master’s degree she’d earned from the University of Maryland School of Social Work. But following the assassination of Robert Kennedy, whose campaign she supported, and the murder of Martin Luther King Jr., she says she hit the pause button on her academic pursuits. Coincidentally, it was during that period that several friends, including some who were also involved in social work, told her about the planned urban highway. They invited her to a community meeting to learn more.

“I heard that people are losing their homes and not getting real relocation benefits, that they’re going build an overpass at St. Casimir’s [the historic Polish Catholic church in Fells Point] and a day care center under the overpass,” Mikulski says, incredulous all these years later. “And they were talking about leveling Federal Hill because it was an engineering obstacle.”

African-American residents in West Baltimore’s Rosemont neighborhood were already fighting it, Mikulski found out, as were residents in Federal Hill. Her friends told her, however, that a lot of folks in Southeast Baltimore were intimidated by taking on the political bosses. The more she heard, the higher her temperature rose.

“People were being bulldozed out of their homes and they were being treated like a commodity that was in the way of this fabricated ‘progress,’” says Mikulski, tapping her fist against the table for emphasis.

After that meeting, Mikulski and others went down to the old Greek-owned saloon on Thames Street to plot their next move. “It’s where The Point is now,” she says. “It wasn’t gussied up. Just a pool-table-and-beer kind of place. We drank some beer and did a couple of shots of ouzo and tried to think of a name for our group that was going to fight the highway. There weren’t a lot of us, but there were enough. I said, ‘We need to come up with something that sounds big. Something that will scare the political establishment.’ So I suggested SCAR—the Southeast Council Against the Road.”

The successful grassroots effort sparked an appetite for politics, and Mikulski used her newfound popularity to launch a bid for a City Council seat in 1971, which she won after knocking on 15,000 doors and wearing out five pairs of shoes.

She’d gone from aspiring to develop the social science research that would help implement Lyndon Johnson’s Great Society to fighting to block Route 70 from running through Fells Point. And then realizing it was the same work in the end.

“City and state officials had a Robert Moses [top down] view of planning, and I was more Jane Jacobs”—the preservationist who led the successful effort to

stop the Lower Manhattan Expressway and save Greenwich Village and Little Italy, Mikulski says. “I believed in neighborhoods and villages and creating

social cohesion. That was the whole point.”

In her U.S. Capitol office. —Photography by David Colwell

All these years later, there still isn’t anything fancy about Barbara Mikulski. She may have introduced the pantsuit to Capitol Hill, but she readily gives credit to her pal Hillary Clinton for taking her ensemble innovation to the next level, fashion-wise. (Several of Clinton’s recently released e-mails expressed an endearing friendship between the two, as well as a shared fondness for Downton Abbey.) She remains “Senator Barb.” She still loves Attman’s hot dogs. “The ones wrapped in baloney are my favorite,” Mikulski says of the family-owned Jewish deli on Lombard Street. She also raves about the Haute Dog Carte on Falls Road. And she still loves the century-old DiPasquale’s Italian Market, the mussels at Bertha’s in Fells Point, and the pies at Hoehn’s German bakery, founded in 1927 in Highlandtown. “Except that Hoehn’s hours don’t seem to work for me,” she says with genuine frustration.

Her mother’s crab cake recipe is posted on her Senate website.

But despite her Charm City “hon” persona, in national political quarters, Mikulski’s name has become synonymous with the modern women’s movement. And while she doesn’t shy away, by any means, from that legacy, her underlying motivation springs from a commitment to economic opportunity and “felt need.” Fighting for equality in women’s health research—funding for studies that discovered a link between hormone replacement therapy and breast cancer rates, for example—defending abortion rights, seeing that women get elected, have been important but not really her primary agenda, Mikulski says. It’s always been bread and butter economic issues.

She remembers neighbors coming into her parents’ corner grocery store on South Eden Street when there had been a downturn at Bethlehem Steel or the shipyards and they needed credit. “I saw when my dad would put something extra in their bag, too. They didn’t turn anyone away,” she says. (As a teenager, Mikulski spent a summer working at Gibbs Preserving Co., one of the canning houses in Canton. “I came home everyday smelling like ketchup,” she says.)

“I’ve focused on equal pay for equal work,” Mikulski says. “Do not privatize Medicare. Do not turn Medicaid into a voucher program. And also, where are the jobs are coming from today? How do we get ready for the jobs of today and tomorrow?”

It’s meaningless, she adds, to pass abstract legislation that doesn’t get implemented and make a difference in people’s lives. “If you don’t know how to do that, all you’ve done is create a hollow opportunity,” Mikulski says, visibly moved as she recalls ex-offenders, with assistance from volunteer paralegals and lawyers, expunging their criminal records recently at the Penn-North branch of the Enoch Pratt Free Library while also signing up for library cards. The “felt need” through-line connects working-class white and working-class black voters as well as women and their families—the coalition that’s enabled her to put together winning campaigns all these years.

She’s only lost once in her life, a premature bid to replace Sen. Charles “Mac” Mathias in 1974 after only three years on the City Council.

“One of the things she told me when I was starting out was not to promise people things you couldn’t deliver,” says Rep. Elijah Cummings, whose district includes West Baltimore. He says the first call he got after being elected to Congress was from Mikulski. “People understand that you can’t deliver everything, she told me. But what they do expect is that you’ll try your best and work hard.”

“We share humble backgrounds,” Cummings adds. “It’s obvious to people that she cares about them.”

Mikulski says her biggest concerns today are drug abuse and the country’s economic “race to the bottom,” as she puts it—the trade policies that promote the shipping of jobs overseas to exploit cheap labor. She voted against NAFTA and has been an outspoken critic of fast track deals. “The bottom is winning,” she says.

“When I started off as a social worker, Baltimore had a manufacturing base,” she says. “You could get a job that paid a livable wage with a high school education and we [at social services] worked to get women into some of those unions, in the garment industry, at Sparrows Point, that were opening up to women. By the time I got to the Senate, you didn’t have that anymore.”

Nonetheless, Mikulski is bullish on Baltimore. She wasn’t a fan of the Grand Prix experiment, which she calls “bread and circus” economic development. But she embraced this year’s inaugural Light City festival, which brought large, diverse crowds to the Inner Harbor and just announced a 2017 expansion. “It reminded me of the old City Fair,” she says. “Sure, some people came after an expensive dinner in Harbor East, and other families came down for an ice cream—but that’s not unique to Baltimore. That’s every city. And it was a Baltimore couple who put it together.”

She may be prickly at times, but at heart she’s an optimist: “I look at that Domino Sugars sign and know there are good union jobs there, and the dredging that’s been done at the harbor will help keep thousands of jobs at the port.” She’s excited by the University of Maryland’s BioPark as well as the local startups and burgeoning tech industry moving into the city’s converted warehouses.

She believes Baltimore is getting its self-confidence back.

“My job is looking at where the jobs of the future are and making sure we’re prepared,” Mikulski says, gently tapping her parents’ dinner table again for

emphasis. “That’s why we need quality public institutions—libraries and schools—for everyone regardless of what ZIP code you live in or economic class

you’re from.”

With President Obama at a Senate women’s dinner. —Official White House Photo by Pete Souza

There is one other Mikulski “first” that is important. In 2012, she became the first woman and first Marylander to chair the Senate appropriations committee, generally considered the most powerful committee in Congress because it controls the purse strings. With the Senate now in Republican control, she serves as vice chairwoman and is the committee’s top Democrat. When Mikulski was appointed to the committee in 1987, it was considered an extraordinary achievement.

“It’s just something that didn’t ever happen for a newcomer, getting appointed to appropriations,” recalls the 83-year-old Paul Sarbanes, who served five terms in the Senate. “But Barbara called me immediately after her election—months before she took office—and we set about putting together a strategy for her.” By capitalizing on her early momentum, Mikulski has delivered federal funding to state projects for three decades, including NASA’s Greenbelt-based Goddard Space Flight Center. (It may help that she’s a science nerd and longtime Star Trek and Star Wars geek.)

While Sarbanes, Cummings, and Cardin certainly appreciate Mikulski’s everywoman touch, they all stress that her ability behind the scenes in Congress—where she is a highly regarded strategist and fierce negotiator—is her real gift. Her nickname among Capitol Hill aides is BAM—as in Barbara Ann Mikulski—and her staffers refer to themselves and are known as BAMers. Of course, the nickname is a nod to her initials, but it’s to her blunt persona as well. True to form, Mikulski embraces the moniker: Her work e-mail address: BAM@Mikulski.senate.gov. When Obama said, “You don’t want to get on the wrong side of Barbara Mikulski,” during her Medal of Freedom presentation, it’s safe to believe the former Illinois senator was speaking from experience.

“She might not have ‘looked’ like what people think a U.S. senator should look like,” Cummings says, “but she is exactly someone people can look to today when they want to see what a successful senator looks like.”

Cummings and Cardin have known Mikulski for more than three and four decades, respectively, but she’s known Sarbanes even longer, dating back to her start on the City Council, when he represented Baltimore in the state House of Delegates.

“He’d taken on the same entrenched establishment as I did,” says Mikulski, who was brash enough during her first City Council campaign not just to visit the Little Italy of then Mayor Thomas D’Alesandro and City Councilman Dominic “Mimi” DiPietro, but to broadcast her stops from a sound truck in both English and Italian. “Sen. Sarbanes’s family owned a restaurant on Main Street in Salisbury,” Mikulski says. “I used to say there were dynasty Democrats and diner Democrats, and we were the diner Democrats.”

Mikulski says Nancy Kassebaum was helpful when she arrived in the Senate, and several male senators, notably Ted Kennedy, quickly became friends as well as advisers. But it was Sarbanes who became her indispensable mentor. She gives him tremendous credit for showing her how to be successful in the “old-boy” network and get things accomplished. The two became close over the years, commuting back and forth to Baltimore every day.

It may seem ironic that a man would’ve been in that mentoring role, but it shouldn’t, Mikulski says.

“My real shining light was Sen. Paul Sarbanes,” she says. “And I want to make sure this gets mentioned. I’ve had the chance to serve with two of the best men in Maryland politics ever. First, with Sen. Sarbanes, and now with Sen. Cardin.”

“You know,” she continues, “there is something else that I’ve learned over years. Men of quality are never in fear of a woman who seeks equality.”