History & Politics

Under Watch

The police spy plane experiment is over, but the growing surveillance of Baltimore continues.

By J. Cavanaugh Simpson

With Ron Cassie

Illustration by Michael Byers | MARCH 2021

This story was produced in partnership with the Pulitzer Center.

eborah Katz Levi, head of the Baltimore City Public Defender Special Litigation Section, knew something did not square. One of her clients, Kerron Andrews, had been charged with attempted murder after he was picked from a photo array of possible suspects following the drug-related shooting of three people in Southwest Baltimore in late April 2014. The Baltimore police subsequently issued an arrest warrant for Andrews and, three days later, found him inside an apartment, which wasn’t his home, just west of Leakin Park. Andrews just didn’t see how the police knew where he was. “Something kept happening to his phone, his phone kept dying,” Levi recalls. She sensed the police or state prosecutors had not disclosed everything in the case. Turns out, she was right.

Baltimore police had secretly deployed an active cell-site simulator, frequently referred to as a stingray, which masquerades as a legitimate cellphone tower and tricks mobile phones within a certain radius into connecting to the briefcase-sized device. The cellsite simulator BPD used had forced Andrews’ phone into transmitting signals that enabled police to locate its precise whereabouts. This part is critical: The simulator doesn't wait for outgoing calls to be made. It actively transmits a signal that travels through walls and reaches into cellphones to conduct a general search of cellphones within the device’s radius.

Initially, Det. Michael Spinnato had been unable to locate Andrews, whom he believed to be in hiding. But he was able to confirm Andrews’ cell number through a confidential informant and then went to court to get Sprint, Andrews’ cell provider, to turn over GPS data from his phone. That information narrowed the search down to the 5000 block of Clifton Avenue and an area of 30 or so apartment units situated around a U-shaped sidewalk. At that point, BPD’s advanced-technical team arrived and, using a cell-site simulator by the brand name “Hailstorm,” pinged the real-time location of Andrews’ phone inside a specific apartment. Spinnato rapped on the door. With the consent of the woman who answered, Spinnato and other officers entered and found Andrews sitting on the couch. His cellphone, it would later come out in court documents, was in his pants pocket. Police secured the apartment, got a search warrant for the premises, and found a gun between the sofa cushions.

In the Circuit Court for Baltimore City, however, Andrews’ lawyers successfully argued the court approval for police to access his Sprint records did not extend to use of the cell-site simulator. The judge ruled use of the Hailstorm device without a warrant was an illegal search under the Fourth Amendment and suppressed all evidence gathered from the apartment as “fruit of the poisonous tree.” It did not help that police failed to disclose the use of the Hailstorm device during the discovery portion of the trial, or that Andrews, currently incarcerated on unrelated charges, had not been picked out from two previous photo arrays of potential suspects.

More disturbing: What came to light as part of another case around that same time was the Baltimore police—which had received instruction from and signed a nondisclosure agreement with the FBI—had long been engaged in the questionable practice of using the phony celltower devices to surveil Baltimoreans. In 2015, a Baltimore detective testified that the department had deployed the technology 4,300 times during the previous eight years without telling defense attorneys, judges, the public, and apparently, any elected officials. In the process, the BPD had temporarily interrupted the cellular service of untold thousands of completely innocent Baltimoreans, who would’ve had no clue why their phone wasn’t working.

“[Baltimore’s police department] makes exceptionally heavy use of the equipment—BPD may even make greater use of its cellsite simulator equipment than any other city, state, or local law enforcement agency in the country,” Laura Moy, a lawyer with Georgetown University’s Institute for Public Representation, wrote in a follow-up FCC complaint. “BPD uses the equipment not only to investigate violent crimes of the most troubling nature, but also to investigate everyday street crimes, to locate witnesses, and for other unspecified purposes.”

...NOT WIDELY PUBLICIZED, BALTIMORE POLICE UTILIZE FACIAL-RECOGNITION TECHNOLOGY AND A SECRETIVE DATABASE WITH EVERY MARYLAND DRIVER'S LICENSE PHOTO.

f you reside in Baltimore City, you’ve seen and heard the police helicopter known as Foxtrot swoop down, flashing its megawatt spotlights. You likely caught glimpses of the city’s first-in-the-nation aerial surveillance experiment last year—Cessna “spy planes,” equipped with 12 cameras, flying in circles, capturing images of people in Baltimore streets and backyards, an effort also initially deployed by police in 2016 without public or elected-official knowledge. If you lived in the mid-and-late 2000s in neighborhoods designated as “high-crime,” a legal term of art used to justify all kinds of police behavior, then you’re no doubt familiar with the surreal blue-light camera boxes once perched atop street poles. Prone to technical problems, they’ve been replaced over time by more than 800 closed-circuit cameras (CCTVs), currently connected to the Baltimore Police Department’s Watch Center. Those law-enforcement surveillance systems barely scratch the surface. Post-Freddie Gray’s death, the BPD has upped its surveillance game. And diversified it.

For now, the “spy planes” are gone. The city canceled the contract in early February. But police-linked surveillance in Baltimore now includes Ring and Nest Hello security doorbell cameras, some of which are linked to the ever-expanding CitiWatch network of public, private, and business cameras. Automated license-plate readers can track a “hot list” of “known violent-crime offenders of investigative interest.” Meanwhile, BPD’s Axon 3 body-worn cameras, meant to help reduce violent interactions with residents, are increasingly equipped with RoboCop-like sensory surveillance capabilities. And though not widely publicized, Baltimore police officers utilize facial-recognition technology, with images submitted for comparison to a secretive Maryland state imagery database that contains all the driver’s license photos in the state. That database is decried by critics as “one of the most invasive” facial-recognition systems in the nation. And then there’s ShotSpotter, an acoustic system that detects and locates firearm discharges. It’s another private-public policing partnership, similar to the 2020 “spy plane” program which had been run by for-profit, Ohio-based Persistent Surveillance Systems.

Baltimore’s police department is not alone, of course, in using these constitutionally gray gadgets. In one Annapolis case, police used a stingray to try to track down someone who robbed a pizza delivery person of 15 chicken wings and three subs. In Detroit, ICE used a cell-site simulator to locate and detain an undocumented immigrant. In Miami, police apparently purchased a stingray specifically to surveil political protestors. As privacy implications mount—algorithm-driven “predictive policing” is already here, and drones are likely on the way—Baltimore’s next-gen spy tech scandals raise a pressing question: Why is Charm City often the laboratory for emerging surveillance technology?

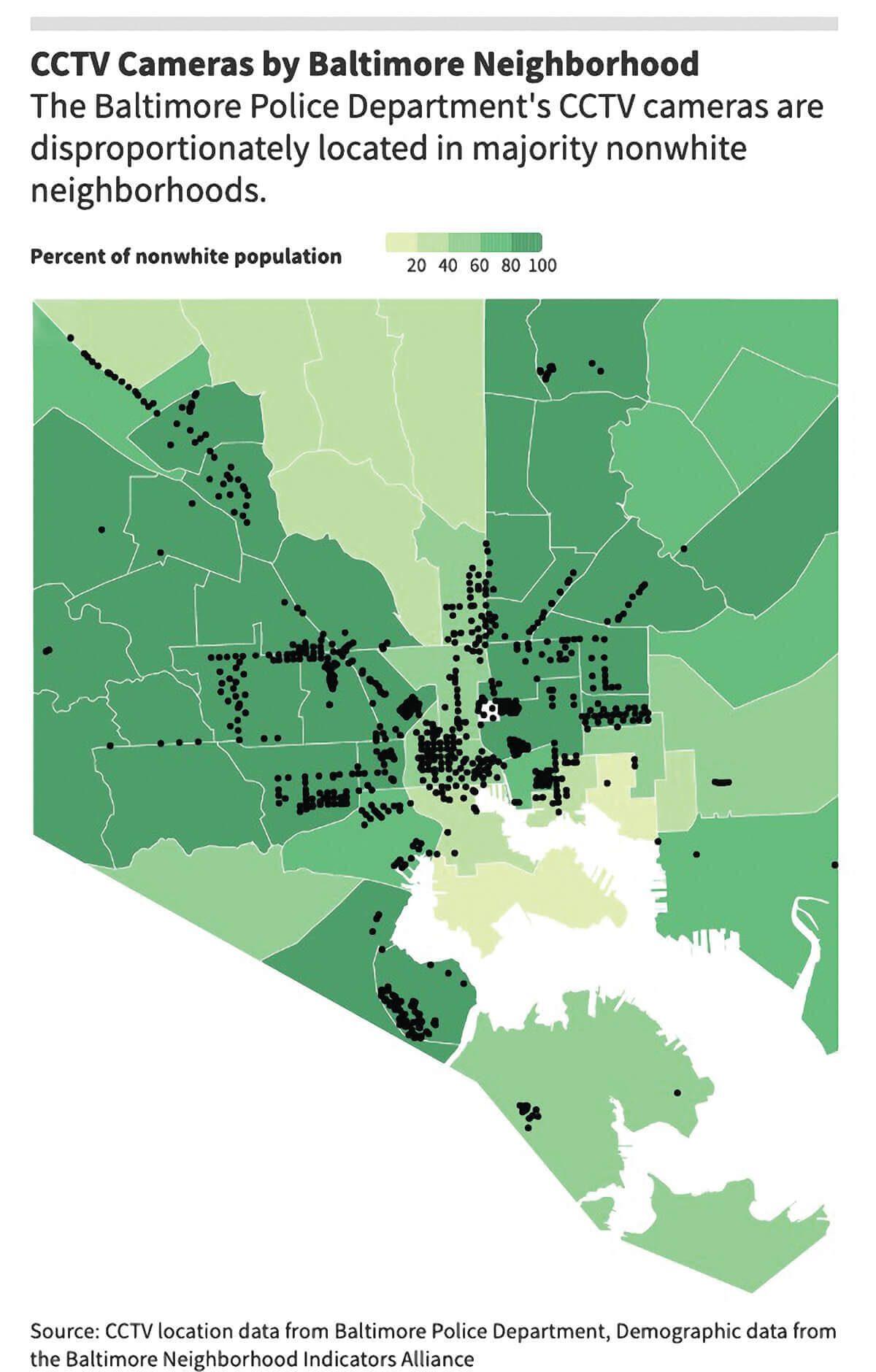

It turns out, we check all the prerequisites for a 21st-century American surveillance state: high crime rates, a lack of police oversight—the Mayor and City Council have little control over BPD policies (the department has been a state agency since around the Civil War)—strained community-police relations, low-income, segregated areas, and most importantly, a history of racially biased policing. In fact, new surveillance technology—even after the scathing 2016 DOJ report that found Baltimore’s police department routinely engaged in unconstitutional practices and racially biased policing—is being deployed primarily, and sometimes solely, in predominantly African-American neighborhoods.

Take, for example, Baltimore’s public-housing complexes, 98 percent of which are considered minority households. More than 180 of the city’s 832 cameras peer from those brick apartment buildings, keeping a steady eye on roughly 14,300 people. With Baltimore’s population hovering around 600,000, that means more than a fifth of city police cameras surveil 0.02 percent of total residents, almost all of whom are Black or Brown.

Or consider last year’s six-month “spy plane” experiment. Under the contract, the planes were supposed to cover nearly the whole city. Yet an astonishing “99 percent of the company’s flights centered on East and West Baltimore—predominantly Black areas,” according to a study from the New York University School of Law’s Policing Project and publicly available flight data. The city’s northern, predominantly white, wealthier neighborhoods, where residents are also concerned about crime, were recorded on only two occasions, the report showed. Late in the pilot program, which had trouble securing a third plane, flight paths were expanded from 32 square miles to 45, partly to address the disparity. Meanwhile, other technologies, such as ShotSpotter, are deployed in the same majority Black sections of the city, five miles each in East and West Baltimore.

“[Police need to] legitimately investigate and prosecute violent criminals, and we all want safer communities,” says Stephen Smith, a retired federal judge at Stanford’s Center for Internet and Society, and a scholar in law and 21st-century police techniques. “[But] is surveillance truly done evenhandedly, or are we tilting it in such a way that it’s really used to surveil a minority community and let everybody else go scot-free?”

“ THERE WAS NO WAY OF COURSE OF KNOWING WHETHER YOU WERE BEING WATCHED AT ANY GIVEN MOMENT. HOW OFTEN, OR ON WHAT SYSTEM ...WAS GUESS WORK”

— GEORGE ORWELL, 1984

here’s no doubt that Baltimore police face a daunting task in solving spiraling violent crime in a city where homicides have jumped more than 60 percent since 2014. So why not tap new tools? Back when fingerprinting was first used, privacy concerns arose. In the early 1990s, newspaper op-eds questioned the legitimacy of DNA evidence. Emerging tech might prove helpful.

Baltimore’s embrace of public safety-oriented surveillance started with 16 cameras some 25 years ago. Faced by rising crime rates in the mid-1990s, BPD used a $75,000 federal grant and another $58,000 from the Downtown Partnership of Baltimore to put up cameras outside Lexington Market. Police officers manned street kiosks to monitor video footage. The 16 cameras, it was hoped, would reduce notable nuisance crimes, thefts from cars and the like. From the beginning, the Video Patrol Program, as it was called, was viewed as a pilot project.

Battle lines between civil libertarians, police, and political leaders were quickly drawn. Some critics predicted the cameras would simply shift crime elsewhere, and the ACLU stressed “we need to tread carefully so we don’t get carried away in the future.” Others believed the camera might catch a suspect here or there, though one local defense attorney cautioned that persistent police camera surveillance of the public square was “a very Orwellian step.”

Then-Mayor Kurt Schmoke dismissed concerns, noting people were already being watched in banks and many retail stores by the ’90s. “Some people get nervous of Big Brother, but I think everyone wants us to make Baltimore safe,” he said. (In a memorable moment, as CBS’s Dan Rather interviewed Schmoke about the project’s “success,” someone smashed the windows of the 48 Hours truck parked 30 feet from a police kiosk. When the program aired, it noted that no arrest was made.)

About a decade later, then-Mayor Martin O’Malley visited London, one of the most surveilled cities in the world, and concluded that cameras could help prevent crime not just downtown, but elsewhere. In 2005, the CitiWatch camera network with private cameras was launched in cooperation with the post-9/11 Department of Homeland Security. Within two years, 400 closed-circuit television cameras, aka CCTVs, dotted the downtown business district, expanding into low-income neighborhoods with high crime rates.

Such technologies, like any policing tools, can help lead to arrests in specific cases. Yet widening surveillance deployment hasn’t proven effective so far in reducing or solving homicides. The Baltimore Police Department cleared only 32 percent of the city’s homicides in 2019, one of its lowest rates in three decades, according to The Sun. And, despite a pandemic that kept many people inside, 335 people were killed in the city last year. That’s fewer than 2019’s per capita record of 348 deaths, but still above the annual average of homicides over the past five years—since much of the new technology was deployed—and among the highest per capita totals in Baltimore history.

How far will the city go down this tech surveillance path? More importantly, will such tools actually help reduce violent crime rates, or will the increasing cost and continued hyper-focus on policing low-income, majority-Black neighborhoods instead perpetuate cycles of mass incarceration and trauma? “The worst thing you can do is say, ‘Well, we’re just going where the crime is,’” says Farhang Heydari, director of New York University School of Law’s Policing Project, which conducted a BPD-contracted civil liberties evaluation of the aerial surveillance program. “We know that crime is not an objective thing. Where police patrol impacts how many crimes they find.”

Lawrence Grandpre, a grassroots organizer and

director of research for Leaders of a Beautiful Struggle, at his office. Photography by J.M. Giordano

he day after the November election, Rev. Annie Chambers sat in a folding chair outside the Harriet Tubman Solidarity Center, saving her strength while she waited for a voting rights march to begin. At 79, Chambers has been a civil-rights activist for more than a half-century and remains formidable. She regularly leads rallies for fair housing, welfare rights, and police oversight. A resident of Douglass Homes, she helps bring food to the hungry, and during the pandemic handed out bags of groceries from her potted plant-lined porch until the Housing Authority of Baltimore City cited rules against food pantry deliveries at public housing complexes. A delegate on the Baltimore City Resident Advisory Board, Chambers has fought against such rules, including recent bans on grilling, smoking, and kiddie pools in public housing community areas. There are few CitiWatch cameras at Douglass Homes, according to city data, and the ones in place are generally not working, said the Baltimore police following the recent daylight shooting death of Safe Streets liaison Dante Barksdale in a Douglass courtyard.

A $3.2-million housing grant is set to fund cameras and other security measures in the community, but Chambers doesn’t believe ever-burgeoning police surveillance deters crime. “Surveillance doesn’t help,” she says, adding that there are cameras perched over any number of city corners where drug dealing occurs. “How does it help when the activity is still going on right by the cameras?”

Some security systems, including flood-lamp trailers, can prove intrusive, alienating the very people that politicians and police leaders are aiming to help. “Police brought in these big old red lights at night that lit up my room, and I couldn’t sleep,” Chambers says, recalling one recent experience. “They told me, ‘You can buy blackout blinds.’”

She says the Douglass community is like many others, including seniors, working people, and children who have grown up seeing confrontations between Black residents and officers. “[The constant surveillance] makes the kids paranoid,” she says. “They don’t even want to talk about what happens with the police and the community.” Russ Mack, a community college student who grew up in several increasingly surveilled neighborhoods, including Park Heights, Pigtown, and Northeast Baltimore, echoed Chambers. “It’s hard to put into words,” he says. “It’s so widespread, it makes you feel like you’re under a microscope all the time. I never got involved with the police, but I never trusted them.”

Overall, BPD’s use of policing tech in predominately Black communities parallels concerns in the Justice Department report that police agreed to address in the resulting federal Consent Decree. In a statement, BPD spokesperson Lindsey Eldridge says the department has focused on solving crimes, implementing “data-driven policing strategies and technology that enhance our efforts in areas that historically experience high crime incidents.” She added that other police strategies focus on added foot patrols and business checks. “We continue to be on the forefront of where the data is leading us to be to deter, prevent, and suppress violent crime.”

Even the city’s housing authority, which also oversees Cherry Hill, Latrobe, and Pleasant View Gardens, notes the cameras have in some cases not helped. There are at least 35 cameras within Gilmor Homes, a cluster of decaying brick buildings, dating back to the 1940s, with 132 walk-up units. Gilmor Homes, part of which was recently demolished, was where Freddie Gray, 25, was picked up by police and placed into a white van in what would become a fatal ride. It’s a place where stuffed animals—a big teddy bear tied to a tree by long-faded ribbons—memorialize the loss of loved ones. The housing authority’s fiscal year 2020 plan noted a “significant amount of criminal and drug activity” in the walk-up units, and that steps taken, including lighting and “strategic use of cameras" have not been successful. A 2017 University of Central Arkansas case study of cameras in Cherry Hill couldn’t reach any conclusion about their impact on crime.

In Baltimore, as in similar urban areas of Philadelphia, Detroit, Chicago, or St. Louis—whose Board of Aldermen has been considering a test-run of the same surveillance planes tried here—people living in disenfranchised communities find fewer resources, including a lack of reliable transit, local jobs, grocery stores, public allocations, and private investment. Rather than address the drivers of violent crime in Black neighborhoods, says Morgan State University public health scholar Lawrence Brown, author of The Black Butterfly: The Harmful Politics of Race and Space in America, Baltimore, like other cities, turns to policing. “It’s this history of economic destruction of Black neighborhoods [that never gets addressed],” Brown says. “Surveillance is rooted in a sort of ‘controlling’ of Black neighborhoods . . . instead of getting at the root cause of why crime is taking place in redlined Black communities. If we’re really serious about getting rid of the violence, then let’s address toxic lead so people’s brains aren’t poisoned in the first place. [Let’s address] the high rates of evictions and foreclosures that push people to the edge. Public health is about prevention, but that’s the last thing we do as a society. Even a lot of police say you can’t arrest and lock up your way out of these problems.”

Lawrence Grandpre, a grassroots organizer and director of research for Leaders of a Beautiful Struggle, a local think tank centered on policy advocacy and Black youth opportunities, is the son of a longtime Baltimore police officer. He also lost an uncle to gun violence. Last April, Leaders of a Baltimore Struggle joined the ACLU in a lawsuit to block BPD’s aerial surveillance initiative. The lawsuit was rejected by a judge, and the planes flew from May through October.

Grandpre notes that there is a nationwide shift in police culture from the old-school “crackheads-and-collect bodies” to a more data-based approach aimed at objectivity. Yet when tech is deployed mostly in Black communities, even if the crime rate is high, it can lead to over-policing and hyper-incarceration.

“Whether it’s a plane, a camera, or police on bikes or in cars, Black people are surveilled all the time,” says Grandpre, himself a victim of an armed robbery two years ago, pointing to studies that indicate surveillance is more effective at preventing property crime than deterring violent crime. “Unemployment and social inequity have been shown to be far more predictable drivers of violence.”

Baltimore Mayor Brandon Scott knows the streets, too. He does not support the surveillance plane initiative, but has a different take on the city’s CitiWatch camera system. Scott grew up in Park Heights, when the clunky, blinking Police Observation Devices (PODs) accompanied the Zero Tolerance-policing era. “When they started off with the bluelight cameras, I was a kid,” Scott says. “The blue flashing lights were just annoying to everybody, especially those people who lived there.” Yet, Scott says, as a Black teen, he felt safer knowing that if something happened to him “it might be captured on camera.”

In many ways, people have become accustomed, for better or worse, to being surveilled in the digital age by private companies and the government, and cameras help some people feel safer. Scott says he hears from Black residents who want the security cameras in their neighborhoods, too, especially in Northeast Baltimore, where he now resides.

“Some of the folks who live up around the Greenmount quarter were like, ‘Well, they have them downtown but not in my neighborhood. Does that mean they don’t think my safety is valued?’”

MAP BY GRACIE TODD, Capital News Service, Philip Merrill College of Journalism, University of Maryland.

ook up at city-owned buildings and streetlight poles these days and increasingly you’ll notice a fisheye CitiWatch lens staring back. Pushed by members Isaac “Yitzy” Schleifer and Eric Costello, the Baltimore City Council last March also approved a $150 rebate for residents who buy an Amazon Ring or Google Nest Hello doorbell security camera, providing they register the device with the CitiWatch Community Partnership. (Currently there are about 850 participants.) Residents who sign up for the rebate must agree to point the increasingly popular cameras at public streets and sidewalks and “should be willing to work with police” to provide video if contacted. In 2020, BPD conducted about 700 “video recovery requests” from non-CitiWatch cameras, including private security and doorbell cams, with owner consent or via warrants, according to BPD.

At a Public Safety Committee meeting prior to the doorbell camera rebate vote, however, police and city officials supplied no proof of effectiveness. Concerns were raised about the undisclosed cost of the rebate program and whether it was the best use of the money. Councilman Zeke Cohen noted the city still needs to find hundreds of millions of dollars to meet educational funding goals set by the state’s Kirwan Commission, according to the Baltimore Brew. Ultimately, Councilman Ryan Dorsey was the only dissenting vote. Such cameras are increasingly found in what’s described as Baltimore’s L—predominately white neighborhoods down the middle of the city and east into Fells Point and Canton. There’s also national controversy over racial profiling via the cameras and related Neighbors apps, with Black and Brown people most often being reported by residents as “suspicious.”

Meanwhile, facial-recognition technology is among the most controversial of new sci-fi-style tech in law enforcement. What’s known about BPD’s usage of facial recognition is murky at best. In one example, after screening aerial surveillance data from the Cessna planes, police tracked a person of interest past a security camera and then “used facial-recognition software to identify the individual,” according to the NYU report. In 2015, Baltimore police used facial recognition and social media analytics to identify some people who took part in the rioting and others who joined widespread protests after Gray’s death, apparently to pursue arrests on outstanding warrants. (That same year, the BPD requested the FBI’s assistance in monitoring protests via aerial surveillance.)

Several cities across the nation, including San Francisco, Oakland, and Boston, have banned police use of facial-recognition technology. City Councilman Kristerfer Burnettt introduced a similar bill last fall, citing a study that current technology misidentifies darker-skinned women in particular, with error rates up to 34 percent. The effort failed in October after a split vote by the Public Safety Committee, partly because police still wanted access to the previously mentioned database of state driver’s license photos, known as the Maryland Image Repository System. Among other uses, it has been searched by federal immigration officers to track down undocumented immigrants. “Once in this database, you are part of a perpetual line-up, always a potential suspect,” Jameson Spivack, a policy associate at the Center on Privacy & Technology at Georgetown University Law Center, wrote in a 2020 op-ed calling for a moratorium on its use. “Federal agencies like ICE and the FBI can run face recognition searches directly on your photo, even if you have no criminal history. And neither you nor a Maryland law enforcement officer would know about it, let alone a judge.”

Somewhat infamously, the New York Police Department scanned a photo of Woody Harrelson from its facial-recognition software to try to identify a beer-store thief who resembled the actor. The NYPD also grabbed a facial-recognition system photo of a New York Knicks player to aid in a search for another man. More alarming, a Towson woman attending Brown University was misidentified in a photo by Sri Lankan authorities as a bombing suspect in her native country, prompting death threats against her and concern for her family overseas.

Maryland’s database, meanwhile, has not been audited by the state in at least a decade. When credentialed law enforcement officials upload photos to the image repository for comparison, there’s no tracking by whom or for what purposes. “People are being charged with crimes and aren’t even being told evidence has been gathered with facial recognition,” says Freddy Martinez, a policy analyst with Open the Government, a nonprofit. “It raises lots of constitution concerns.”

Some new tech, such as body-worn cameras, come with a promise to increase police accountability, and hopefully offer protection for citizens and officers alike. Adopted in May 2016, the Axon Body 3 cameras have cost $18.4 million to date, according to BPD, mostly through city general funds. According to BPD officials, complaints of “discourtesy and excessive force” have dropped dramatically since officers began wearing cameras. However, an 2020 op-ed calling for a moratorium ACLU-MD review released in January pushed back strongly against that contention, reporting misconduct complaints filed against 1,826 Baltimore officers from 2015-2019, with 91 percent of use-of-complaints stemming from interactions with Black residents.

The body-worn camera’s ability is also expanding. Axon Body 3 cameras now offer GPS, gunshot detection, and “livestream,” a function meant to support officers in a crisis. Yet the idea of citizens being recorded in real time by roving video sentinels has prompted privacy concerns—imagine families being livestreamed in their home as police conduct a search. Upgraded cameras boast clearer HD images as well. While police are barred from real-time facial-recognition scans under BPD policy, that guardrail does not prohibit BPD from utilizing facial-recognition software to analyze the video from a specific incident.

There’s another element to all of this surveillance that needs to be addressed: The developers of new technology sweep into crime-ridden cities promising grand solutions. But while new tech can offer legitimate crimefighting tools—and the purveyors are generally convinced their technologies will help— there’s a clear profit motivation, as well. Take ShotSpotter, the technology that detects gunshots. According to an investor presentation in November, ShotSpotter had placed 17,000 sensors in more than 100 municipalities. The company hopes to expand to 1,400 cities, a potential annual market of $560 million. The investor website, Seeking Alpha, in a summary post headlined “The Good, The Bad and The Ugly in ShotSpotter,” noted the “technology does not seem to be fully mature yet,” including numerous alerts which do not result in injuries, or false alarms that might just be construction or cars backfiring.

In this public-private partnership, with initial funding from Bloomberg Philanthropies, Baltimore officers are also required by department policy to report gunshot detection alerts that turn out to be false to ShotSpotter, to help the company improve its technology.

In fairness, such tech also has potential to be helpful. Residents might not report gunfire, out of ongoing distrust of police or fears of retribution from shooters. The BPD says since 2018, ShotSpotter technology “has produced 1,275 founded calls”—confirmed gun discharges—improving police response time and offering data to assist patrols.

An infusion of federal grants, philanthropy dollars, or private cash can help a budget-strapped department. But it raises questions about local accountability, as well as the rapid application of unproven tech. “If someone else is paying for it, police are going to adopt it,” says Eric Piza, an associate professor at the John Jay College of Criminal Justice, who studies policing technologies. One prominent example: Local police departments have been quick to apply for free surplus military equipment—high-powered weapons, tactical vehicles, combat gear—ever since a Clinton Administration initiative to strengthen police ability to fight the War on Drugs was launched in 1997. (That effort, known as the 1033 program, often gets blamed for the militarization of U.S. police forces and is still in place.)

Joyous Jones at Simmons Memorial Baptist Church in

Penn-North, the site of a sidewalk shooting during morning services in October. Photography by J.M. Giordano

oyous Jones looked to the aerial surveillance planes in the sky for her community’s salvation. Jones, a retired nurse, is an elder at Simmons Memorial Baptist Church in Penn-North in West Baltimore, where she has watched open-air drug markets thrive. “I counted 350 drug transactions in one hour, in daylight. It’s almost like a McDonald’s drive-up.” She regularly overhears sellers shouting out different names for heroin, sometimes laced with fentanyl, and other drugs. “They yell out, ‘I’ve got Take You to Hell,’” Jones says. So she turned on the church’s outside loudspeaker and said, “Don’t get Take You to Hell, we have something to take you to heaven.” She adds: “They yell theirs, and we yell ours.”

Jones, like other parishioners, knows the sorrow of having a child victimized by street violence. Several years ago, her son was stabbed and rushed to University of Maryland Shock Trauma. He survived, despite losing a liter of blood, but two young men on either side of him died. Such losses feel endless. She describes a death last year in the all-too-familiar language of homicide reports: “Number 304 died in a shooting in the 4100 block of Glenmore. He was one of our deacon’s sons.”

Still, nothing could quite prepare her for what happened on Sunday, October 11. The church was holding its regular outreach, offering donated coats and blankets, curbside prayers, and a hot oatmeal breakfast in the neighborhood. After morning service started, about 20 people were still outside. In a tragic coincidence only possible in Baltimore, Wayne Waite, an attorney with Persistent Surveillance Systems (the for-profit surveillance plane operator) was talking, microphone in hand, with the congregation on behalf of the company’s rebranded Community Support Program. Suddenly, a dozen shots rang out. Church members rushed to the front door to see what was happening. Jones saw people dropping to the ground and behind cars. Her nursing instincts drove her outside to “see if they were hit and to move everybody inside.” Lamont Randall, 27, lay bleeding on the sidewalk while church members prayed. He died there. The plane wasn’t flying that day due to weather, but Waite later tracked down CCTV video of the suspect, who was caught on camera sauntering away.

Jones had at first been skeptical of plane surveillance. But the more she heard about what the technology could do, watching company videos demonstrating suspects being tracked, the more she felt it was needed. Community activist Archie Williams felt the same way and, with Jones, joined the company’s outreach effort, visiting community associations and churches to drum up support for the aerial surveillance pilot, whose contract eventually was approved by former Mayor Jack Young. She later served as the company’s local office manager, hiring video analysts from the community. “If we don’t do anything, we won’t have any children left,” she says. “Our children deserve the right to have life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness. And it’s our responsibility to provide that for them.”

Jones and Williams were not alone in their support. Recently, a post-pilot University of Baltimore poll put public support for surveillance planes at 55 percent. Such surveys, however, often leave out context, as noted by David Rocah, senior staff attorney for the ACLU of Maryland. When it comes to aerial surveillance, the survey doesn’t address the fact that they have not been shown to be significantly effective (a recent preliminary RAND Corporation report found a slight benefit). Nor did it address the constitutionality of such surveillance. In a 2019 interview with The Appeal, Rocah described one such survey (paid for by the Abell Foundation), which found even higher support for the planes, as a “push poll.” “If you ask people whether they would like to reduce murder in Baltimore, who would say no?”

major surveillance issue with Baltimore police is who scrutinizes the scrutinizers? In recent years, the department lost even more public trust with subsequent revelations of corruption and dysfunction related to the now-infamous Gun Trace Task Force. So who makes sure the technology programs are equitably and evenhandedly used? This is an ongoing question.

In 2017, in another high-profile case, an assistant attorney in Deborah Katz Levi’s office found that a Baltimore officer wearing a body camera appeared to plant evidence. The cop didn’t realize the camera was on when he walked into an alley and put a plastic baggie full of heroin capsules into a soup can. Officer Richard Pinheiro Jr. claimed he was recreating the discovery of the drugs. A year later, he was found guilty of evidence tampering. In another highly publicized incident, a BPD officer turned off his body camera at the request of former Baltimore prosecutor and then-mayoral candidate Thiru Vignarajah, who at the time was the target of a 1 a.m. Greenmount Avenue traffic stop—a courtesy not likely extended to most drivers.

Either because of the publicity or other reasons, body-camera footage uploaded by police and reviewed by state prosecutors is often no longer straight video of an arrest, start-to-finish. “They can edit, they can cut or blur, they can mute and do all kinds of things,” Levi says. “There can be a false sense of security if you see something on video.” (Video footage is stored in a cloudbased subscription system called Evidence. com and operated by Axon Enterprises, Inc., formerly Taser, whose first product was an electroshock weapon.) One homicide case included more than 600 files of video snippets, says Levi, who calls the system “an informational nightmare.” She emphasizes she doesn’t want to ditch the technology, which can provide exculpatory evidence, but points to improvements such as a return to full video, automatic edit trails, and better officer identifiers on the video.

While BPD has become more transparent since Commissioner Michael Harrison came on board in March 2019, that transparency doesn’t come cheap. For this story, police assessed the cost of a Maryland Public Information Act request for records and emails from several city and police officials about the Ring camera rebate at a prohibitive $49,816.

However Baltimore’s policing tech plays out, it likely won’t be easy to track. Other futuristic surveillance systems already under consideration or in use here include drones and “predictive policing,” a controversial crime forecasting algorithm tool that taps crime data including “chronic offender” lists to “predict” where and when crimes are likely to occur. In March 2019, the city’s Board of Estimates voted to renew a contract with Strategic Focus LLC for $635,000, a program, again, being deployed in the Eastern and Western Districts. That vote came just one day after a scathing inspector general report on the Los Angeles Police Department, where the program originated, citing audits of lackluster results in crime-reduction, and noting concerns about its “use in Black or Latino communities.”

In the end, stronger watchdog protocols seem critical. There’s a bill currently in the Maryland legislature to give Baltimore local control over its police department. The elected City Council’s oversight of police policies and practices, as well as a more powerful Civilian Review Board, would be a start.

“The bottom line: Technology like this should never be rolled out without a clear law, one that has been democratically approved,” says Heydari with NYU’s Policing Project. Whether or not departments deploy new policing tech, leaders should consider and regularly evaluate how their choices affect disenfranchised citizens. The Stanford-Harvard Project on Technology and Policing in a 2020 emerging technology “tool kit” calls for annual public reports detailing any impacts on residents’ “civil liberties [and] racial, ethnic, and religious equality.”

Ivan Bates, a Baltimore defense attorney and former prosecutor who ran for City State’s Attorney in 2018, acknowledges some benefits to newer technologies. One of the surveillance planes in 2016 turned up evidence that later led to an overturned conviction for one of his clients. But that evidence was disclosed by a reporter, not city police. “The question is how the technology is going to be used and how the police are using it,” he says.

Critics of Baltimore’s growing surveillance state also say some private companies are essentially preying on the city’s despair by experimenting on Black residents. Bates doesn’t disagree. He compares the current scenario to past experiments in the Black community, such as the Tuskegee study, in which African-American men who had syphilis went untreated for 40 years, while health researchers charted the disease’s progression. Closer to home, a 1990s Johns Hopkins-Kennedy Krieger Institute study, which tested the efficacy of lead remediation in city rental housing, knowingly allowed children to be exposed without sufficiently warning of the risks, according to a 2001 Maryland Court of Appeals ruling. A damning study of that effort published several years later in the American Journal of Public Health was titled, “With the Best Intentions.”

“You have that foundational makeup of the Black community already not trusting the majority community,” Bates says, “which has decided that they will try out new things on Black people.

“People don’t trust government, they don’t trust Big Brother, and they don’t trust the police because of what has happened over the years. It could be a great technology that will really help, yet because of Baltimore police’s history, people are going to be leery.”