Home & Living

A Light King's Lair

There’s a certain order to the retro chaos of Rand Dorman’s home.

At first glance, Rand Dorman’s home seems like just a riot of stuff.

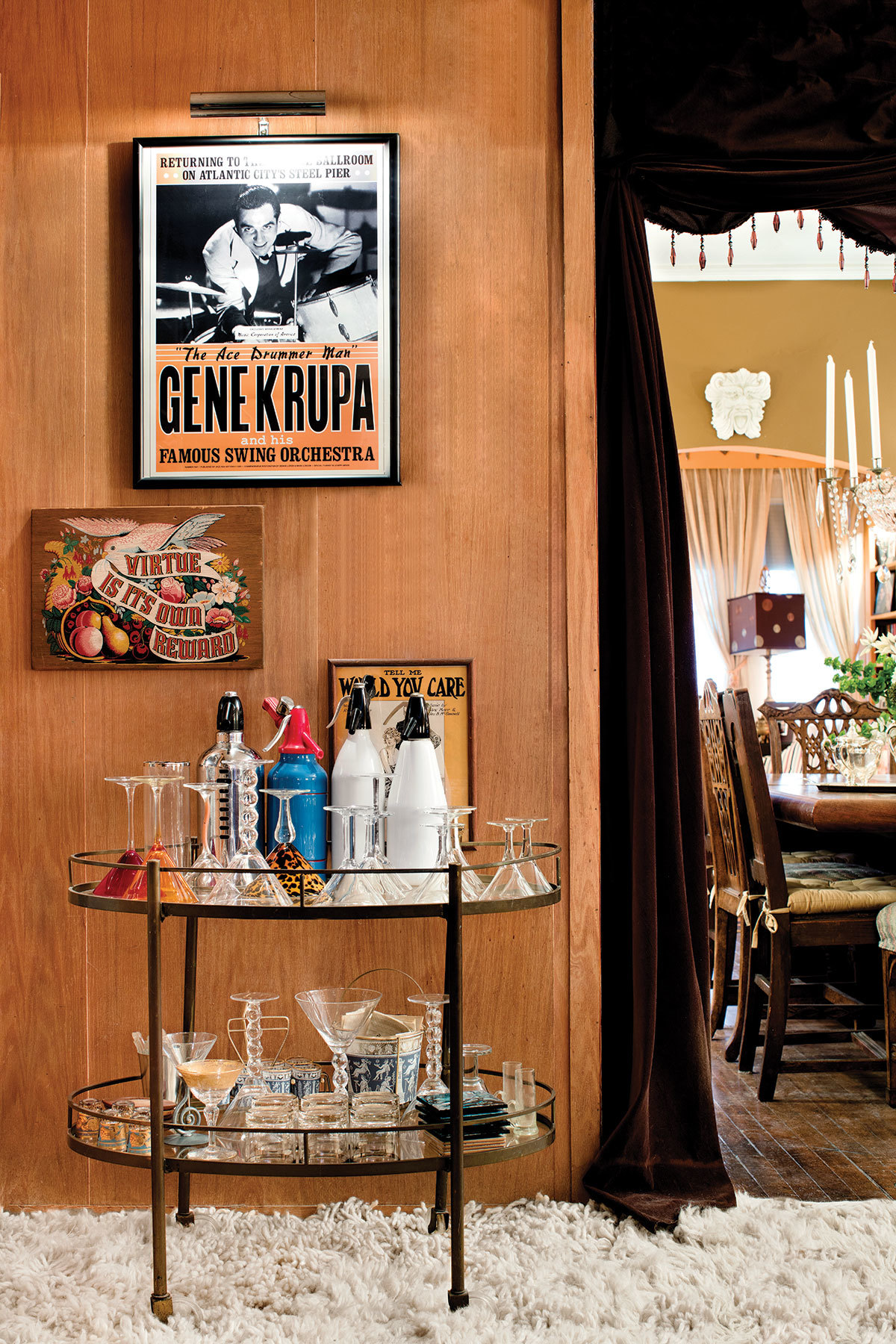

There are collections of monogrammed silver serving pieces, a bar cart with a half-dozen old seltzer bottles, and an array of typewriters and rotary-dial telephones. The midcentury shelving in the den is loaded with vinyl albums, and nearby is a vintage hi-fi and a plastic Show N’ Tell record player from the ’60s.

The room is a tribute to Dorman’s upbringing a half-century ago, complete with thick shag carpet and a leopard-print sectional sofa with those corduroy tufted throw pillows that have a covered button in the middle. The 50-inch flat screen TV embedded in the wall interrupts the time warp, though Dorman has added a touch of whimsy by perching rabbit-ear antennae on top of the set.

Dorman, whose family runs 76-year-old Dorman’s Lighting in Lutherville, has even wired the old radios and record players to pipe Pandora and iTunes through their speakers. “It’s easy to hook them up,” he says. “But you have to be careful. Some of the old tubes still have electricity in them. I once got a hell of a shock.”

Rand Dorman, named after writer Ayn Rand, gave his English bulldog a more whimsical name, Thurber, after the 20th-century humorist; No room is spared the chandelier treatment, though the pantry offers a brighter décor than other spaces. —Photography by Jennifer Hughes

Throughout his Northwest Baltimore home, which he shares with his bulldog Thurber, wherever you turn, your eye falls on something quirky, something familiar from your own childhood or that of your parents or grandparents. In the kitchen, shelves of 1950s- and ’60s-era electric mixers and bright orange and turquoise cookware share space with black lacquered cabinets and a 1958 Tappan oven with an enamel-lined warming drawer. A bubbling chrome coffeepot on the stove sends off an enticing aroma. “The best coffee is percolated,” Dorman insists. “Joe DiMaggio ruined everything.” (He’s referring to the baseball legend’s TV ads for Mr. Coffee drip coffeemakers in the 1970s and ’80s.)

Somehow, these eclectic collections unify. Or maybe it’s just because everything is so impeccably lit.

“I love lighting,” says the 52-year-old. When he enters the house—a modest 1920s bungalow—he need only push a button on his Leviton control system to switch on all the lights. “To turn them on one at a time would take forever and a day,” he says, underscoring the point by gesturing toward the strips of tiny bulbs hidden under the lips of bookshelves, soft lamps on end tables, cove lights in the ceiling, and multiple crystal chandeliers that have all come instantly to life. But none are too bright.

“It’s all on a dimmer,” Dorman points out. “Everything looks beautiful when you can dim the lights.”

The vintage stove produces Dorman’s famed chocolate-chip cookies (on plate); a bar cart in the den displays collections of seltzer bottles and martini glasses.

—Photography by Jennifer Hughes

At the family business, he frequently instills customers with that ardor for illumination and design that’s in his DNA. Dorman’s grandfather, Gerson, started Dorman’s Electric, a supply company, in 1941. The business, now owned by Gerson’s son, Rand’s uncle Stanley, once had showrooms in Catonsville, Severna Park, Baltimore, and Timonium, but now has a single location on York Road in Lutherville.

The younger Dorman, who eschews a title, works in sales “and whatever is needed,” he says.

At the suggestion of a friend, he recently took over an unused conference room in the store as a mini jumble sale for castoffs and redundancies from his home to keep his personal collection under control. Every time he watches Hoarders on television, he gives away “six or seven lawn-leaf bags of stuff,” he says. The re-purposed room’s recessed lighting now shines down on vintage radios, assorted china, and a bedside lamp in the shape of a bright red purse. “I could see it against a white painted brick wall in some girl’s Canton condo,” he says. His aunt, Linda Michel, has dubbed the space Rantiques. Customers who come into the store for a lamp occasionally find themselves leaving with one of the collector’s knickknacks.

Named by his mother after Ayn Rand, author of The Fountainhead, Dorman grew up in Owings Mills, attended boarding school in upstate New York, and planned to work in the food service industry.

After studying at Johnson & Wales culinary school in Rhode Island, Dorman began making desserts for Charles Levine Caterers. He recalls getting a raised eyebrow from his boss after a fancy party, when he had taken a break from kitchen duties to dance with a guest, then Sun columnist Laura Charles.

The neon “Eat” sign above the sink was a gift from Dorman’s friend, former Sun columnist Laura Charles.—Photography by Jennifer Hughes

He counts Charles as a friend (she’s also the mother of actor Josh Charles). It was Charles who gifted Dorman the neon “Eat” sign in the kitchen and the buffet in his dining room. A life-size suit of armor stands in the corner, one of the few inauthentic pieces in Dorman’s collection.

“I had to have it—like in Scooby-Doo,” he says. “There’s always a suit of armor.” The piece doesn’t bend, so he and a friend drove it home in a convertible. “You should have seen us,” he says. “The metal parts were flapping in the wind and kids coming home from school were hysterical.”

At home, Dorman’s collections are everywhere. Full sets of gold-rimmed china line shelves in the basement stairwell. He has a particular affinity for obsolete or nearly obsolete products. To wit, he’s bought up containers of 20 Mule Team Borax, Arm & Hammer Super Washing Soda, and Brasso polish and glass wax in anticipation of those products permanently disappearing from stores. In the center of the laundry room is an old-fashioned “mangle,” or automatic ironing machine. “You just feed it in and in 30 seconds you have a perfectly ironed king-size sheet,” he says.

He calls the basement the “control center”—it’s home to all the wiring for lighting and sound systems. There’s even a CO2 tank with tubes connected to the contemporary seltzer machine in the kitchen.

So what drives him to embrace all the trappings of yesteryear?

“When I was 5 or 6, I watched old movies on TV—MGM musicals, nightclub scenes, Katharine Hepburn coming down the stairs with a beautiful chandelier hanging above, Clark Gable and Cary Grant dressed for dinner,” Dorman recalls. “I thought life was like that. But something happened around 1968. Cars started getting ugly, clothes started getting ugly. I decided I wanted my life to be like the old movies, that era of fine things—elegance, attention to detail, beauty in everything. But it’s gone. At least in my eyes.”

Dorman, however, has the antidote for that: He just goes home and flicks on the lights.