Home & Living

Frankel's Follies

The home of the man behind AVAM’s Sideshow is as funky as the store.

Ted Frankel is the first to admit that his Mt. Vernon row home isn’t, you know, normal. “It’s who I am, so it’s not everybody’s house,” he says. “It’s an artist’s house and a comfortable house.”

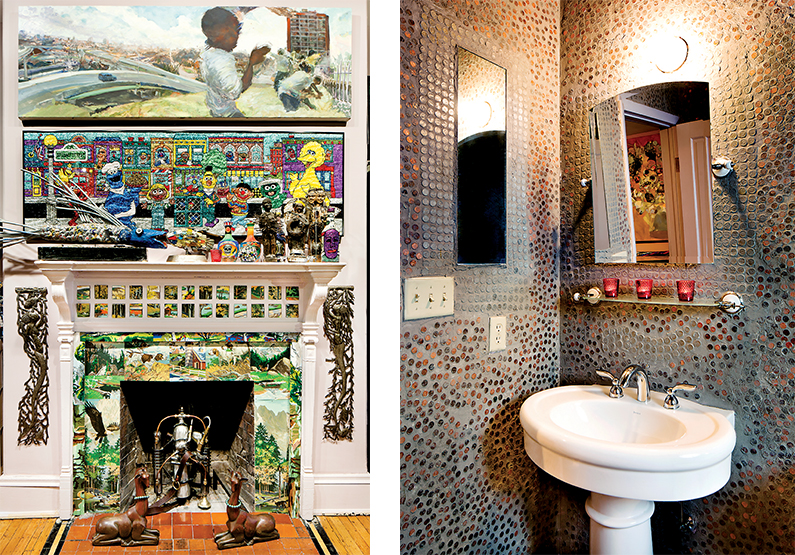

As he says this, he is nestled in the corner of a fire-engine-red sofa, with a comically caricaturish bust of Lincoln and an array of bric-a-brac perched on three small tables behind him. To his right, the fireplace surround sports a colorful paint-by-numbers collage and on the walls all around is art as far as the eye can see.

This will come as no surprise to anyone who has ever set foot in Sideshow, the American Visionary Art Museum’s (AVAM) raucous gift shop, which Frankel opened in 2004 to offer up original art, funky jewelry, novelty toys, and oddball gifts that range from the quirky to the absurd.

That he lives in Baltimore at all was a bit of an unlikely development for Frankel, a Cleveland native who for nearly four decades owned and operated three similar shops in Chicago. He’d gotten his start on a bit of a whim—the then-art director and lifelong “junker and collector” snapped up an about-to-close novelty store in its entirety when the owner refused to sell him only the items he really wanted.

Frankel soon expanded that operation, which began in just 300 square feet of retail space, and was firmly established in the Windy City when a trip to Baltimore with a friend changed everything. Visiting AVAM with visual artist Nancy Josephson (creator of the glittery mosaic bus that sits outside the museum), Frankel suddenly found himself face to face with museum founder Rebecca Hoffberger.

“She was giving a tour and stopped the tour and gave me a hug and said, ‘It was nice to meet you,'” says Frankel. “We talked for maybe two minutes.”

It was the briefest of meetings, and yet, two months later, when Hoffberger was looking to rejigger and expand the museum’s gift shop, she called Frankel. “She said ‘You’re the one,’ and I said, ‘The one what?'” Frankel recalls with a laugh. “I said, ‘I have three stores in Chicago and I’m not moving to Baltimore.'” But Hoffberger persevered and after another, longer meeting, “it sounded and felt right,” says Frankel. “I’m a very spiritual business person.”

Decision made, Frankel quickly snapped up the Mt. Vernon house, which came with the condition that it be reconverted from apartments to a single-family home.

The move was a daunting one: Frankel was adept at opening and running stores, but he had just one friend in Baltimore. “It was scary, but I wasn’t afraid,” he says. “I think fate brought me to Baltimore.”

At the museum, Frankel chose the name Sideshow for his shop, “because it’s not the main attraction, it’s sort of where the freak lives.” More than a mere retailer of quirky goods, Frankel wanted Sideshow, like his other stores, to be a reprieve from the rules of the real world, “sort of the safe space on the Monopoly board,” he says. “When I create a space, I’m really comfortable and I hope the people who come in are really comfortable.”

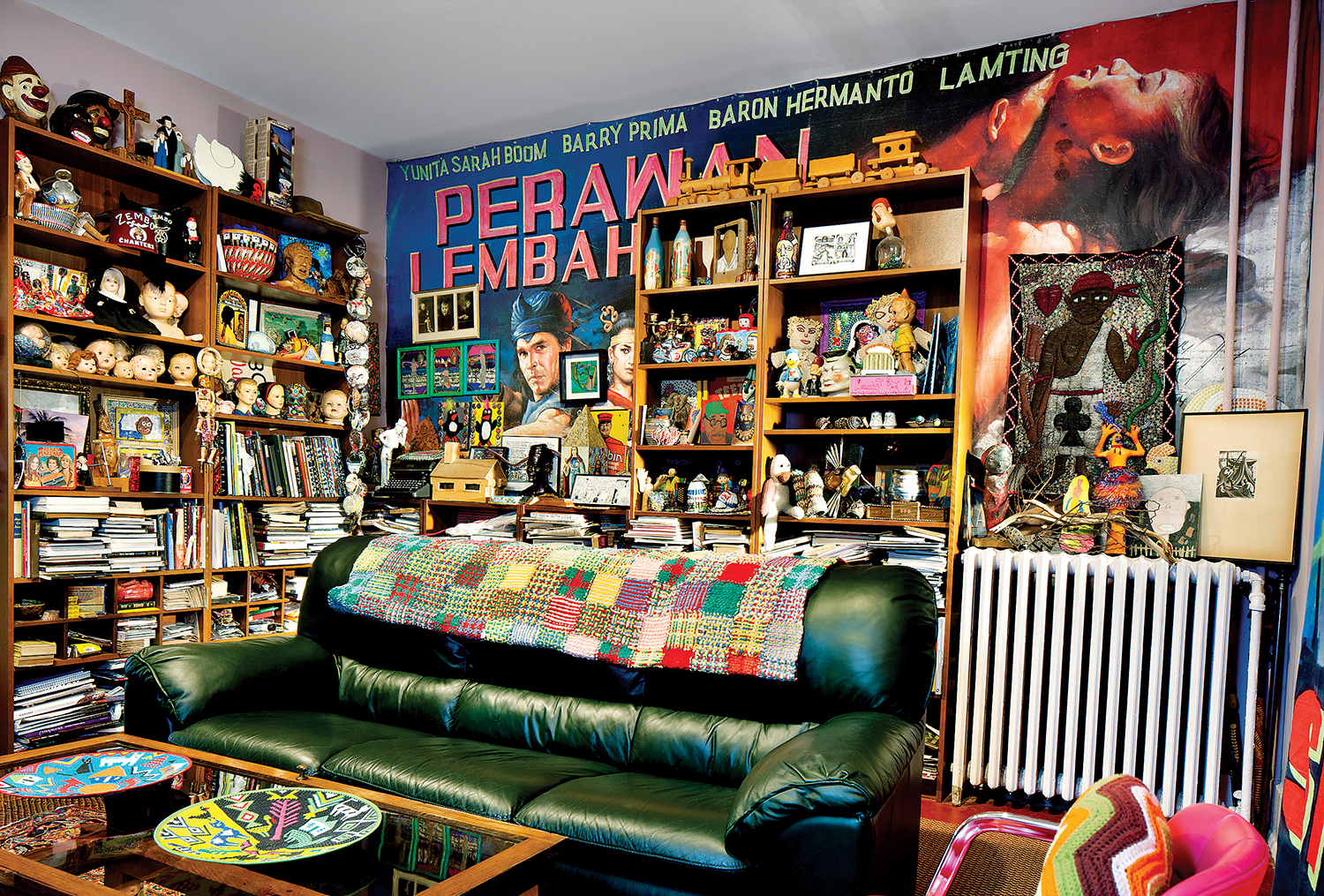

Bringing that vision to reality proved easier than you might think. Frankel’s signature retail setup—think old wooden fixtures and lots of little drawers “because people like to explore things”—proved ideal for the location. Filling those shelves wasn’t hard either, mostly because Frankel is always on the lookout for items that amuse or inspire, whether it’s self-adhesive mustaches, handmade jewelry, outsider art, or even squirrel underpants (seriously). The result is part treasure trove, part fever dream.

“People who really get it, go, ‘What an incredible collection of stuff—or crap,'” says Frankel, who knows that, for some people, the store, like his home, may be visual overload but adds, “I wouldn’t have it any other way.”

Similarly, at home, Frankel would find filling the space no problem. For a person who believes “anything touched by human hands is special,” art is all around. “All I wanted was a house with good bones and I could do the rest,” he says. But the remodeling process dragged on, leaving Frankel to crash with his sole Baltimore friend for months. “Eventually, I ran out of money and trust in the contractor,” says Frankel. This forced him to abandon his plan to paint the home’s walls a bright hue and, instead, leave them neutral. “It works,” he says, shrugging. “There’s so much great art in the house, that people don’t really notice.”

That brings us, of course, to the art, which covers nearly every inch of those neutral walls, hangs from the stairwell and the ceilings, and sits atop tables and shelves. It includes mini-portraits made from sock threads of prison inmate Ray Materson, offbeat family-life paintings by Martin Mull, and jarring Matt Sesow paintings that hang on an upper floor landing. Then there’s the chandelier crafted almost entirely of spoons (and the one cobbled together from clear plastic hangers), the velvet Elvises, and the coin mosaic walls in the guest bathroom. There are even paintings and sculptures created by Frankel, though he rarely points them out to visitors. “It’s fun to see if they react to them,” Frankel says.

Whatever the piece and whomever the artist, ultimately the decision to display it in the home comes down to gut instinct. “You buy what you like,” as Frankel says. “If you’re going to live with it, you want to be surrounded by things that either inspire you or amuse you or make you happy.”

Frankel had barely gotten Sideshow up and running when his connection with Hoffberger yielded an unexpected benefit: “Rebecca set me up on a blind date with my now-husband,” he says. That would be Bill Gilmore, head of the Baltimore Office of Promotion & The Arts, and a former art director like Frankel.

As he got to know Frankel, Gilmore also got to know the house—and its collection. “You can’t take it all in at once because it’s sort of like getting to know the person,” says Gilmore, whose own home-design style leans more contemporary.

“Still, I related to it. I could certainly appreciate it and understand it,” says Gilmore, though, like Frankel, he admits, “it’s not going to be for everyone.”

The two were soon splitting their time between their two homes and, before long, adding to the collection became a team effort, with pieces gathered from galleries, thrift shops, flea markets, and art school sales—locally and from the couple’s travels to far corners of the world.

On their travels, Frankel and Gilmore connect with artists of all stripes, sometimes through introductions by Hoffberger, though even their chance encounters are almost by design. “I sort of believe you should live with an open heart and open eyes—never walk down the street on the same side,” says Frankel, who recalls stumbling across a visionary artist in Cartagena, Colombia, just because, “I happened to go down the right street.” Spotting the painting of a grinning donkey and slightly suspicious-looking cow that now hangs in his living room, “I took it off the frame and rolled it and carried it home,” he says. “I pretty much always come home loaded up.”

Frankel and Gilmore have a history of charitable works here and abroad. Among other efforts, they raised $40,000 for art and medical supplies following the 2010 Haiti earthquake. But in 2013, they went a step further, creating an arts-focused charitable foundation under the umbrella of the Baltimore Community Foundation.

In 2013, nearly 10 years after they first met, Frankel and Gilmore officially tied the knot in a small private ceremony officiated by Baltimore City Mayor Stephanie Rawlings-Blake. A later reception at The Cloisters, where Hoffberger had first approached Gilmore with the idea of a blind date, was bigger, and in line with parties at home that Frankel and Gilmore have become known for.

“The way we throw a party is always really great food and casual, which always makes it comfortable,” says Frankel, whose annual holiday party at home draws 200-plus guests, ranging from the museum’s cleaning crew to the governor.

Like Sideshow, the home is “a touch-it house,” says Frankel, which means guests are free to explore the entire home and its works. “We have little kids that come in and they want to play with the vintage toys and that’s okay,” he says.

And while his collection often grabs visitors’ attention, it also offers a way for Frankel, who calls himself “kind of shy,” to comfortably connect with anyone who enters his home. As at work, where Frankel can often be found cheerfully filling in customers on where and how a piece was made, at home he delights in sharing the story behind the art.

“Everything has a story,” he says. “So, no matter what they point at, I can start talking about it. Hopefully, when people leave my house, they know a little bit about me.”

And it’s Frankel’s hope, too, that they’ll get something more—the chance to share the feelings the pieces invoke, the chance “to be touched by the human element.” After all, even if it’s not everybody’s art, Frankel says, “someone’s hands and mind have made it.”