Home & Living

Ready for Prime Time

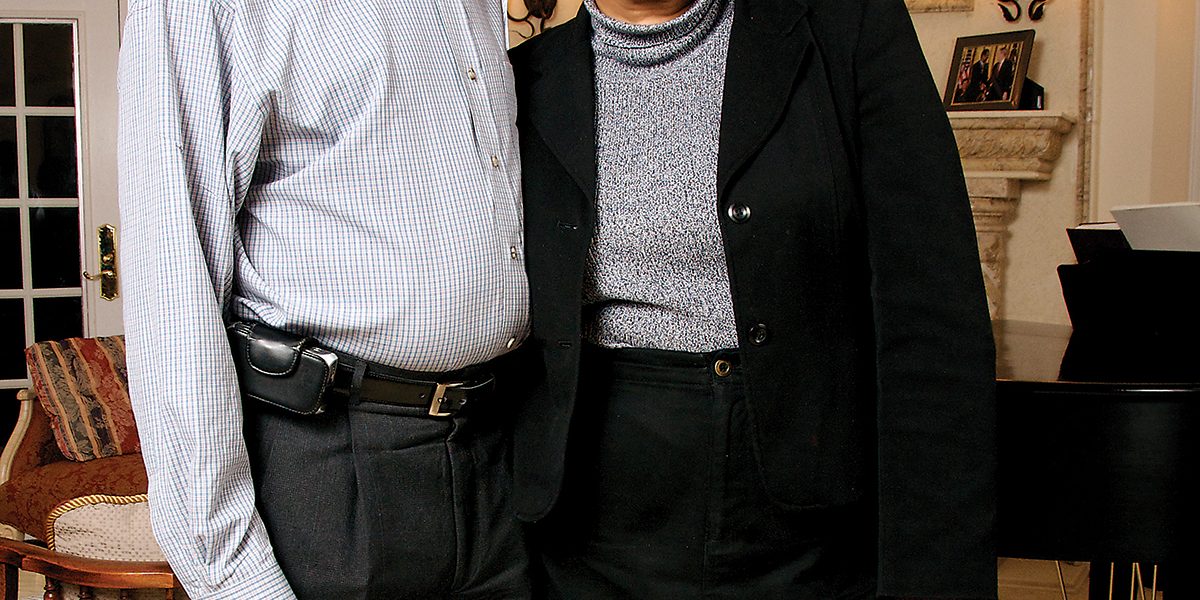

As he reflects on his extraordinary career, Dr. Ben Carson is now willing to open his house—and his life story.

Lacena “Candy” Carson wanders around the basement family room of her Georgian-style, Baltimore County estate—hammer in hand—performing an extremely familiar task: She’s tacking up plaques and prizes belonging to her husband, Dr. Ben Carson, the internationally-renowned pediatric neurosurgeon.

On this brisk fall night, Candy has fallen a bit behind in her efforts, as she hangs Carson’s 2007 honorary doctorate degree from Columbia University and his plaque from Baltimore magazine’s Top Doctors 2007, alongside the other honors that fill the walls, glass cases, and specially built niches throughout the residence.

The family room, where Carson likes to unwind over games of pool, ping pong, and foosball, is a sort of makeshift museum of the man known for his gifted hands, and Candy is both keeper and curator. A quick glance at the cases and walls reveals more than 50 honorary doctorate degrees from such institutions as Spelman College, Morgan State University, and Yale as well as certificates, trophies, and statues from numerous preeminent organizations.

“It took me about 12 hours to put all these up,” Candy says with a sweep of her arms around the room. “I had to lay them on the floor first to get the proportions just right. I wanted it to be art—not just a bunch of plaques on the walls—and I still have so many to put up that are still in storage.”

That’s two down for tonight with dozens more to go, because as soon as Candy hangs one award up, Carson has another bestowed upon him, including the nation’s highest civilian award, the Presidential Medal of Freedom, which he won last year.

“You wonder why this house is so large,” jokes Carson’s mother, Sonya, whom Carson credits with his success and who lives in a third-floor suite of the 48-acre, eight-bedroom, 12-bathroom family home.

If these walls could talk, they would share the oft-told story of Carson’s hardscrabble beginnings in Detroit. The story goes that Sonya, who worked three jobs to support Ben and his brother Curtis, pushed her boys to great academic heights despite her own lack of education (Sonya’s formal schooling ended after third grade) and struggled to survive as a single mother. Carson was initially a poor student, but with his mother’s encouragement and insistence on education, he went on to graduate from Yale University and the University of Michigan Medical School before, at 33, becoming the youngest-ever director of pediatric neurosurgery at The Johns Hopkins Medical Institutions. He gained worldwide recognition in 1987 as the principal surgeon in the landmark 22-hour separation of the Binder Siamese twins. (The surgery was the first time twins joined at the back of the head had been separated with both surviving.)

“Tell them that God is my publicist!”

While many doctors in the Baltimore area have earned international acclaim, not many have a fan base so strong that they can’t go out in public without being stopped for an autograph.

“It’s funny,” says Carson. “Years ago, somebody told me that someone at one of our competitor institutions was asking, ‘Who is Carson’s publicist? How does he get so much press?’ I said, ‘Tell them that God is my publicist!'” Carson chuckles at the memory. “I never sought any attention of any type,” he says. “But it has continued to come, and it’s clear that it’s never going to go away, so I make the most of it.”

One example of making the most of it: Carson gave television network TNT the green light to make a movie about his life: Gifted Hands: The Ben Carson Story, based on the bestselling book of the same name, will air on February 7, in conjunction with Black History Month. Oscar-winning actor Cuba Gooding Jr. plays Carson. For more than a decade, various production companies have attempted to woo Carson into making a movie of his life, but the timing and artistic intentions never felt right to him—until now.

“I certainly didn’t want to do the movie too early,” says the 57-year-old. “I still had years to practice. Once you are the subject of a movie, it has a tendency to have an impact on your life and how people perceive you. I said to myself, ‘I’d rather do it as I’m approaching the end of my surgical career as opposed to 10 years ago.'”

And make no mistake, strictly entertaining viewers with his life story was not Carson’s goal.

“He didn’t agree to do this for the sake of entertainment,” says Gifted Hands executive producer Dan Angel. “The mission is that it will reach people from all walks of life across the country. He wants people to see his story not because of ego. He wants people to believe you can overcome anything with faith, with family, with a dream.”

Indeed, Carson’s story so inspired Cuba Gooding Jr. that the actor calls meeting the doctor for the first time “magical.” “My experiences [making the film] have changed me as a man and father,” he says. “And they will only continue to shape me.”

While the soft-spoken Carson is humble, he is also surprisingly happy to put his home on display as an obvious marker of his success.

“I don’t shy away from the fact that financially we’ve done well, and it’s not just from medicine,” he says. In addition to taking on close to 400 medical cases a year, Carson sits on the board of several for-profit corporations including The Kellogg Company and Costco Wholesale Corporation, and gives motivational speeches across the country. “I get lots of money to go around and make speeches,” says Carson. “And I’ve got real estate in different places. One of the points I like to make with young people is that you can do that without being an athlete or an entertainer.”

Carson feels the media reinforces the image of sports and entertainment as the only roads to riches for African-Americans. “Look at The Cosby Show,” he says. “You have a physician married to a lawyer, and they live in this okay place, but I never appreciated that the show that came on right after Cosby was Lifestyles of the Rich and Famous, in which these rappers get into their limos after they get out of their mansions and onto their private jets. You juxtapose that to what a doctor and lawyer are making, and it sends out the message that you can go out and get all this education but you’re not going to go anywhere with it.”

For the purposes of depicting his own odyssey—from humble roots in a cramped house in Detroit’s Deacon Street (“that was our dream house and it was not even as big as my garage is now”) to his current home, Carson felt it was important to show what money can buy when you achieve academic success.

“It’s not the home, it’s the people that make it a great place.”

“I don’t necessarily want kids to do something for money,” he explains, “but I want them to understand that when you develop yourself intellectually, you become valuable to society in many ways. You don’t have to take a vow of poverty.”

When the Carsons moved to their house in 2001 (from Howard County), they were actually only intending to buy a large plot of land.

“There’s no question I loved the idea of space,” says Carson. “Having grown up in places that were not very spacious with lots of people around, I liked the idea of having your own space, and the idea of being so secluded really appealed to us.”

But as they drove around the neighborhood, they found more than just a plot, they found a home. “I said, ‘Wow! This place has potential,'” Carson recalls. “‘We could do some things with this—we can add a portico, a circular driveway, and landscaping.'”

Carson was inspired, and so was Candy, who got busy on the interior as soon as they moved in. She knocked down walls on the first floor to create a more open floor plan and added a state-of-the-art kitchen where family and close friends (including Maryland State Schools Superintendent Nancy Grasmick and husband, lumber magnate Lou, and Baltimore publisher, Steve Geppi and wife Mindy) gather for her famous vegetarian meals and after-church Sunday brunches.

While their home oozes European style and sophistication—with a hand-carved antique dining room buffet, Chippendale-style dining room chairs, crystal chandeliers, and high quality oil paintings—Candy, an inveterate bargain hunter, says she purchased much of the furniture at the Laurel Auction.

“Did I ever imagine I would live in a place like this?” she asks. “Of course not. Growing up poor, you try to be a good steward of the money you have.”

Since both Candy and Ben were raised poor, they have been careful to keep their three sons (Murray, 25, Ben Jr., 23, and Rhoeyce, 22) grounded. The boys grew up mowing the lawn, helping around the house, playing musical instruments, and watching the example of their parents, who give away and raise large sums of money for the Carson Scholars Fund. (To date, the Carson Scholars Fund has provided more than 3,400 scholarships to high-achieving students.)

“The one thing I’ve noticed over the years is that the children of a lot of people we know who are quite affluent have not done well,” says Carson. “Being determined that our children would not grow up that way and that they would understand the value of hard work and the value of money, we’ve been very careful not to spoil them. Growing up in hardship was a tremendous advantage to me. It puts fire in your belly and gives you the will to keep going when people tell you you should quit.”

Their strong faith is also a guiding force. “We are very spiritual people so you will see a lot of Bibles around the house and things that are indicative of that,” says Carson, who attends a Seventh Day Adventist Church in Silver Spring. “I don’t have to be politically correct here.” He points to a stained-glass window in his foyer, a painting of him with Jesus, and his favorite proverb over the fireplace—”By humility and the fear of the Lord are riches and honor and life”—Proverbs 22:4.

Carson also loves being a Baltimorean, although it took some time. “I came here in 1972 to look at Hopkins Medical School before renovations began, and I said, ‘Do people actually live here?'” he recalls. “I couldn’t believe how bad it was. Four years later, when I came back for residency, they had done a lot of work and have been going gangbusters ever since. I think Baltimore is one of the great success stories in our nation when it comes to urban renewal. Now, I love it here, and this would be my preferred place to live.”

Still, it’s the people, not the place, that matter to him most. “I have the most supportive and wonderful wife anyone could ask for,” says Carson. “I don’t get attached to things. If tomorrow I lose everything, and I’m back in a house like I grew up in, it won’t be the end of the world. It’s not the home, it’s the people that make it a great place.”