Home & Living

If These Walls Could Talk

For these five families, the homing instinct remains strong.

According to U.S. Census data, the average American moves about 11 times in his or her life, a statistic that confirms what many of us know from experience: Thanks to moves necessitated by jobs, schools, and relationships, “home,” is more of an ephemeral concept than a physical place these days. But that’s not true for everyone, including the Baltimoreans on the following pages, each of whom is part of a family that has kept its homestead for 100 years or more. In Baltimore City, such domestic dynasties are recognized via the Baltimore Heritage Centennial Homes Program, which will celebrate 10 families this month with a reception at City Hall. Though there is no corresponding program in Baltimore County, there are certainly many qualifying families, and we talked to one Catonsville woman who lives in the same house her grandfather built in the waning years of the 19th century.

Here’s to those who have stayed.

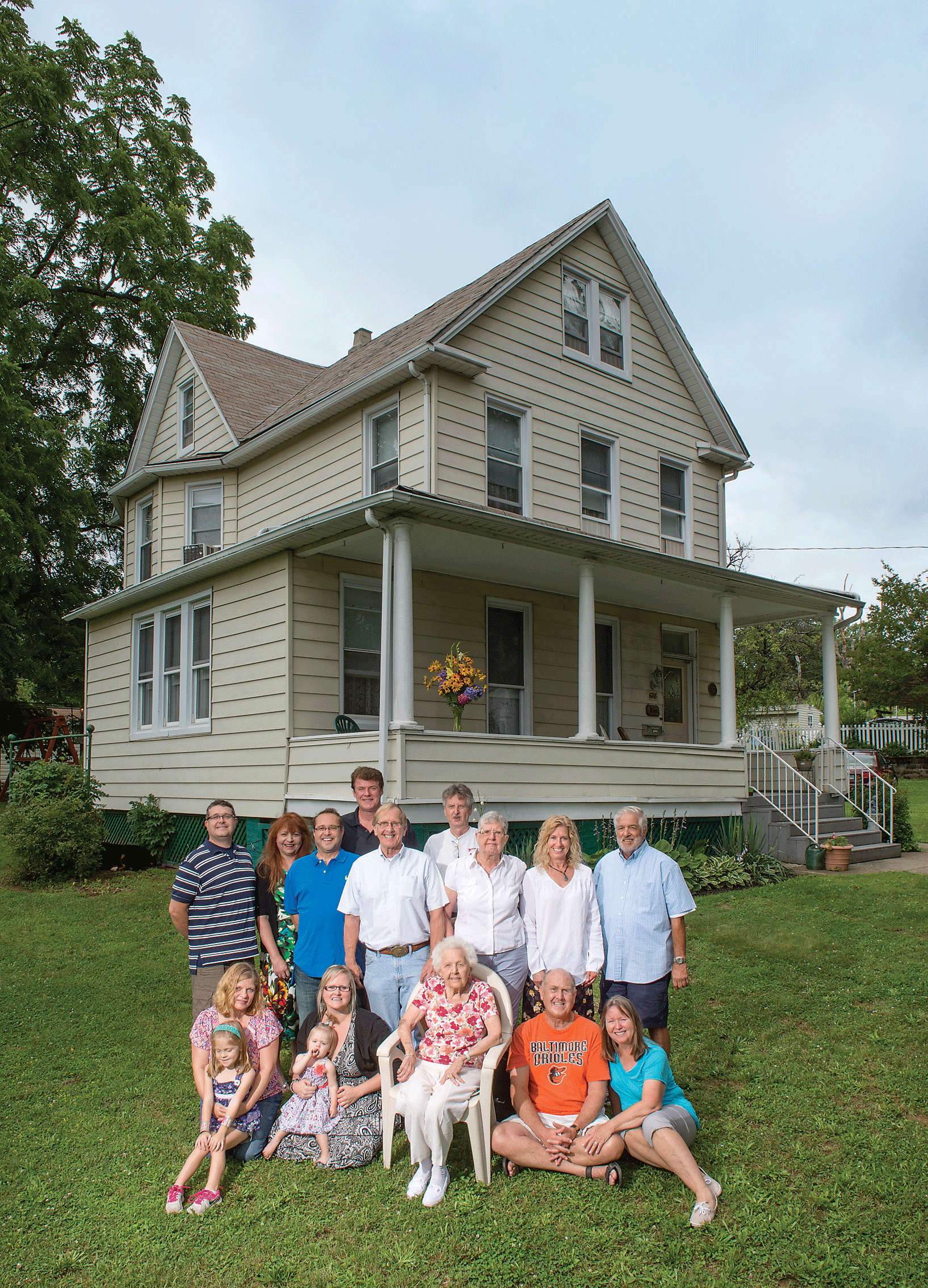

Constantine Rist wanted his family out of the city. Like many first-generation Americans, the German immigrant sought the American dream, and, in 1905, that meant moving from congested, industrial Baltimore to a newly constructed farmhouse on a dead-end lane in Overlea. Though this portion of Overlea would be annexed by the city in 1919, in 1905 it was still a garden suburb. In the three-bedroom house, Constantine and his wife, Mary, raised four children, plus two grandchildren after their oldest son, George, and his wife, Georgia, died of tuberculosis. In 1940, their second-oldest son, Charles, married Norma Schwarz of nearby Hamilton, a union that would eventually produce five children. In 1955, after the deaths of both Mary and Constantine, Norma and Charles moved into the house. Norma, pictured center, seated, remembers the transition as a smooth one, since they had been living

“The kids go out and play, and, as long as you showed up at 5 o’clock for dinner, nobody really worried too much.”

only about five blocks away in a duplex. “[The duplex had] a small yard, so this was much better for the kids.” says Norma, who, at 94, still reigns as the family matriarch. So while Charles worked—first for a local business called Black & Decker and then for the Baltimore City police department—Norma tended house. The children, including John, now 66, played outside with neighborhood kids. “Times have changed since then,” admits John, pictured left of his mother, standing. “There was a kind of thing where the kids go out and play, and, as long as you showed up at 5 o’clock for dinner, nobody really worried too much about it.”

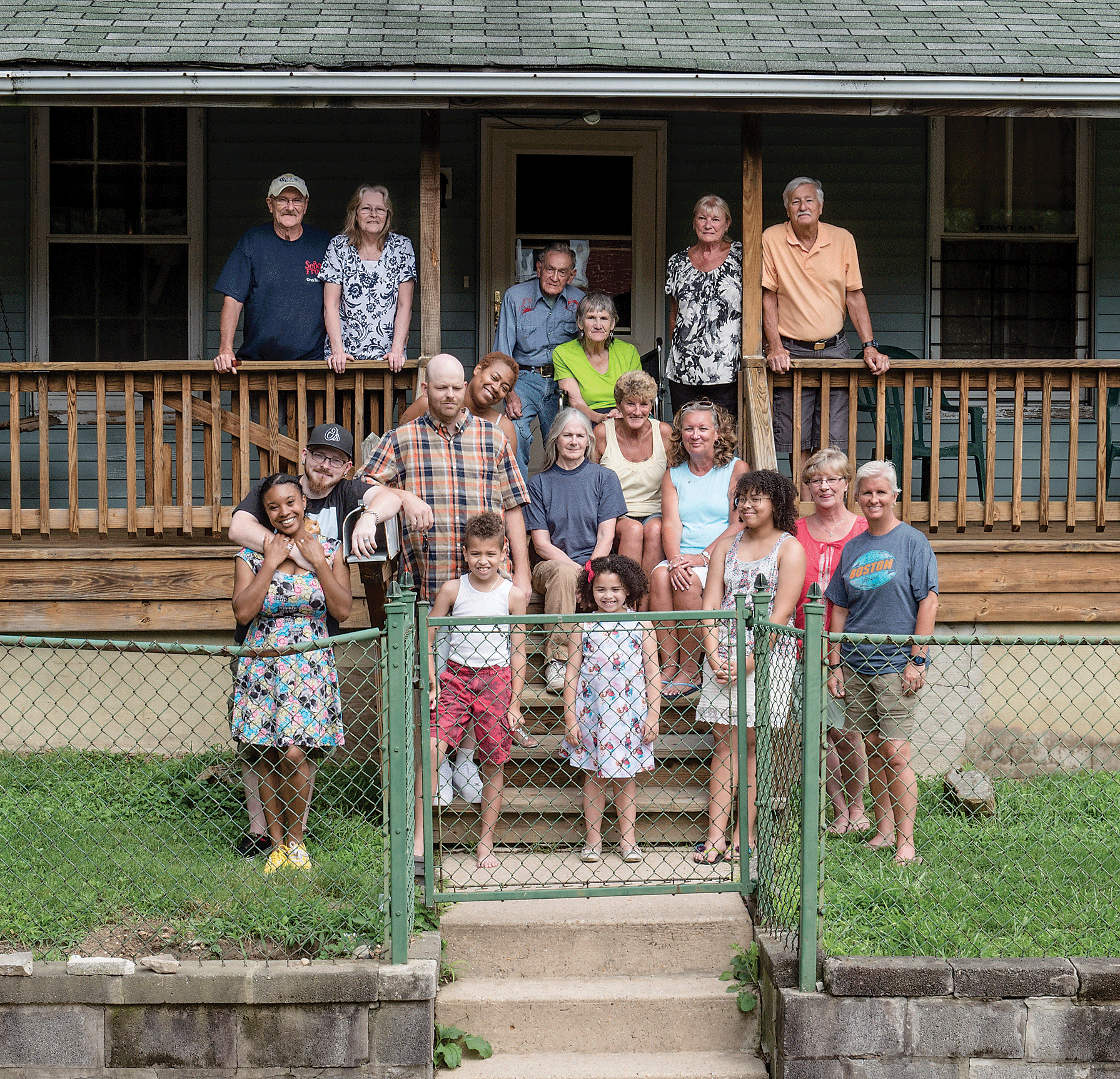

No one’s exactly sure when the flat-roofed house perched high above the narrow Waverly street was built. As far as the Smith family is concerned, it has always just been there. In all, seven generations of the clan have lived in it, starting in the 1870s and continuing today with Joshua Smith, on steps in plaid shirt, his wife, Katrina, behind Josh, and their three children Joshua II, Kassidey, and Kristiana, front row, from left. “Everybody lived here, pretty much, at one time or another,” says Joshua’s father, Franklin, who is part of the family’s fifth generation, along with his sisters Arleen, JoAnn, Patsy, and Regina. Franklin, on porch, far left,

“With Memorial Stadium nearby, the Smith family, ‘Never had to watch the game to know what was going on.’”

and his sisters grew up in the house, and they all fondly remember dips in their in-ground swimming pool and the roar of the crowd during O’s games at nearby Memorial Stadium. “We never had to watch the game to know what was going on,” recalls JoAnn, seated on steps in yellow tank top. Franklin inherited the house in the early ’90s from his parents, Pat and Betty, who moved to the county after winning $4.25 million in the Maryland Lottery. “They bought the ticket in Ocean City when they were visiting my sister, Arleen, down there,” relays JoAnn. Joshua bought the house in 2008 and plans to leave it to his kids. The house’s oldest living former inhabitants, Bill and Mary Ellen Coggins, standing and seated at top of the porch steps, lived in the house for a few years after their 1949 wedding before moving across the street and then, eventually, out to Bel Air, where they still reside. Asked if he misses the neighborhood, Bill, who turns 90 this month, offers a simple and sincere, “Oh yeah.”

Though the two-and-a-half-story row home has been in her family since 1891, Jane Buccheri freely admits she was largely indifferent to it until it became hers. “This is a terrible thing to say,” says Jane, a retired Department of Defense worker, “but my sister, who is three-and-a-half years older remembers being in this house as a kid—I don’t.” Jane has lots of memories of the house now, of course, having owned it since 1978, but she’s as surprised as anyone that she ended up with it. “It went through what I call the family chain of command,’” she cracks. The house entered the family in 1891 when her maternal grandfather, Walter O’Crean, bought it. Walter was one of many Irish immigrants in the neighborhood and, like most, he found work with the B&O Railroad for a time before launching his own manufacturing company, specializing in boilers. (Walter Anglicized the family’s surname to Crane early on, though it’s unclear why.) After his first wife died, Walter remarried and, between both marriages, fathered nine children,

“My sister, who is three-and-a-half years older, remembers being in this house as a kid—I don’t.”

the youngest of whom, Elizabeth, was Jane’s mother. Walter died when Elizabeth was only 13, forcing her to quit school and find work at the B&O. She married Sylvester Buccheri in 1939 and together they raised four children in nearby Irvington, and then Glen Burnie. Once Jane’s grandmother’s health began to decline, she came to live with the family in Glen Burnie, leaving the house with renters. After her death in 1958, the house went to Jane’s uncle, then Jane’s aunt, then Jane’s older sister, Marianna. Knowing Jane was looking for a place in the city, Marianna suggested Jane take it, and the rest is family history. Though Jane traveled extensively for her job, she never got the itch to leave Baltimore permanently. “It’s always nice to come home,” she says.

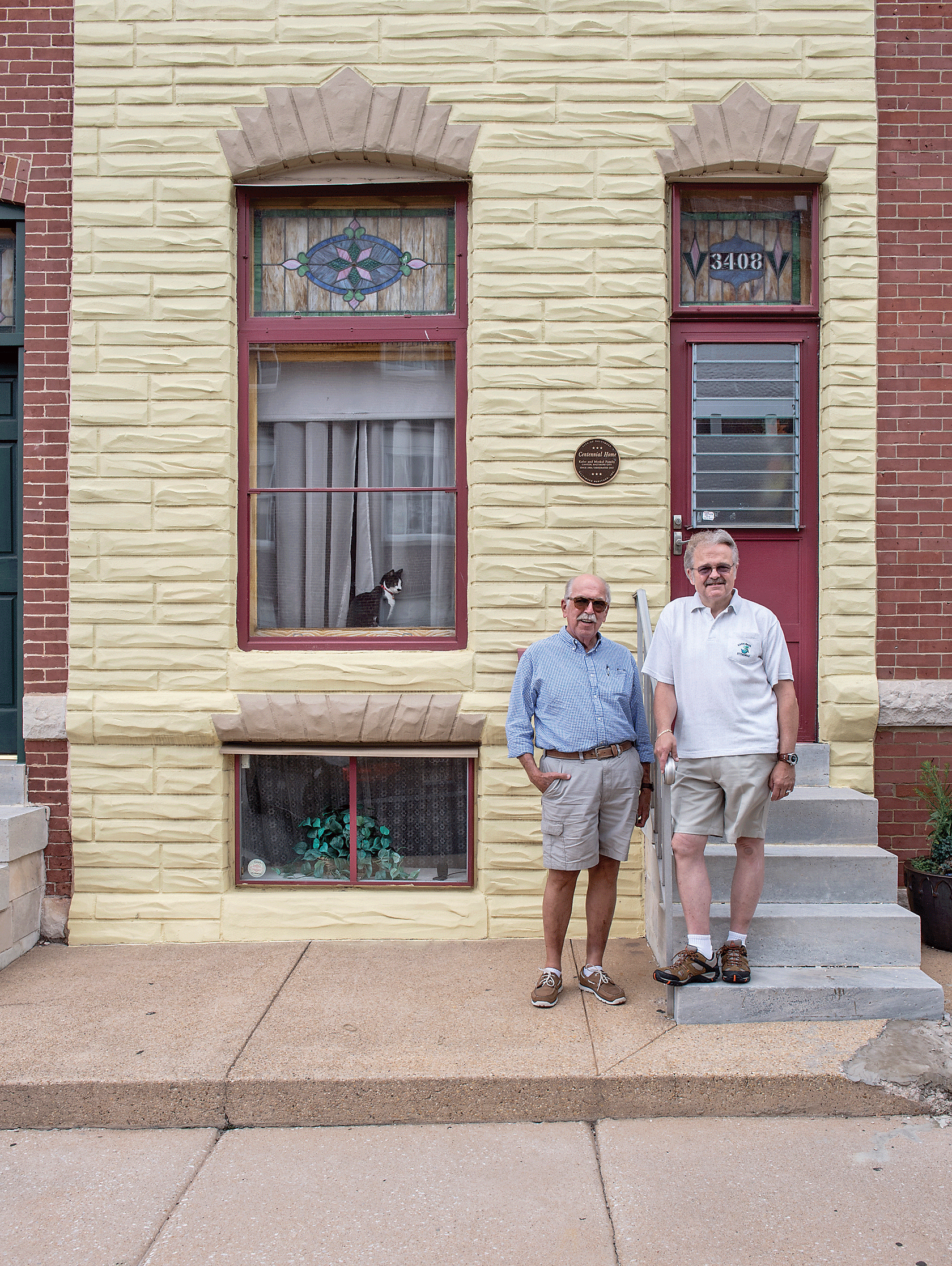

Brothers Roland and Arthur Moskal have their maternal grandmother, Maggie Williams, to thank for the family home. She purchased the then-new Canton row house in early 1904 for $540, and paid it off within 18 months. There hasn’t been a mortgage on it since. Sometime after 1905, Maggie met Michael Kafer and they had two daughters, the youngest of whom, Doris, would become Arthur’s and Roland’s mother. Because Maggie died when Doris was only 7, Doris’s older sister, Edna, became like a second mother to the young girl, and the sisters remained close, their respective families sharing the home until 1960. In 1946, Doris married Joseph Moskal, a merchant marine from the neighborhood, and they had sons Arthur, right, and Roland, left, in quick succession. To hear Arthur and Roland tell it, growing up in 1950s Canton was exactly like you’d imagine: They played curb ball up the street, made beer runs to the National Bohemian

The Moskals’ grandmother purchased the house in 1904 for $540 and paid it off within 18 months.

brewery for the adults, and called to their neighbors over the back fence. In the ’60s, Roland, in particular, got caught up in the counterculture, playing in a hard-rock band, and, by his own admission, spending much of his time in altered states. Eventually, though, he became a Baltimore City schoolteacher, retiring in 2007. All throughout, he remained in the house, sharing it with his parents until his mother died in 1984, and his father entered a nursing home in 1988. Arthur moved out at 20, in part to escape butting heads with his strong-willed mother. He is retired from banking and now lives at the beach in Delaware. With no close kin left, Roland and Arthur are acutely aware they are the end of the line, but they are sanguine about it. They say they’re not in any hurry to sell, but home values in the gentrifying ’hood are increasingly favorable. Thank goodness for Grandma Maggie.

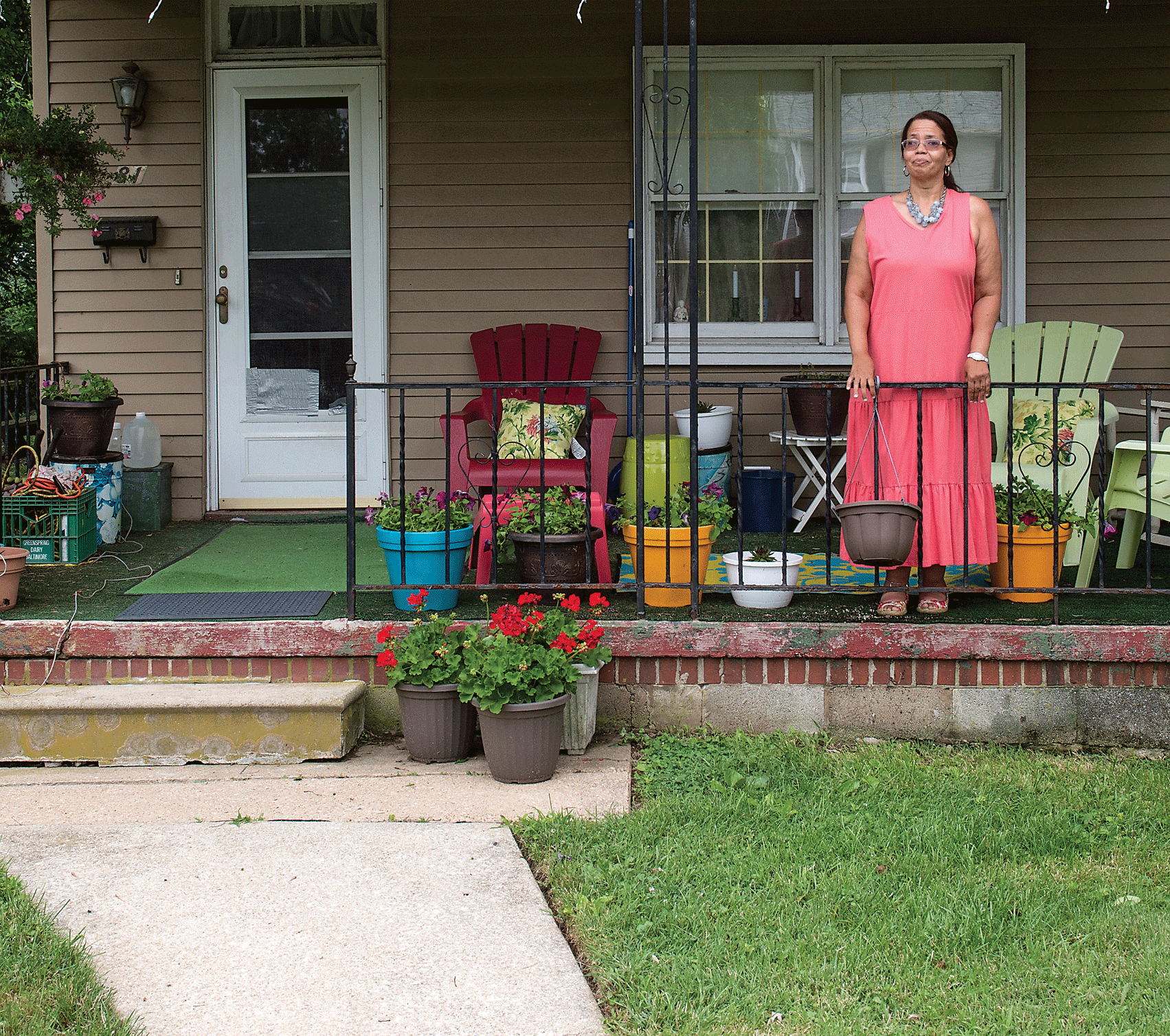

Denise Eileen Washington is the third generation to inhabit her family’s cozy cottage on the outskirts of downtown Catonsville. Her grandfather, William Washington, a Kentuckian born just after the Civil War, built the house circa 1897. In it, he and his wife, Mary Jane Muir Washington, raised their nine children, the youngest of whom, Rufus, was Denise’s father. While working as a clerk at the Social Security Administration in Woodlawn, Rufus reconnected with a young secretary he’d known growing up—Arey Jenson of Ellicott City. They soon married and had daughter Denise in 1958. Though an only child, Denise says she never felt

“My uncles and my aunts were here at least once a day. . . . family was always around.”

lonely, partly because she loved to read and could therefore always entertain herself, and partly because the house was always so busy. Only one of her father’s siblings moved out of state, and four of them lived within walking distance. “My uncles and my aunts were here at least once a day. [One of] my aunts lived across the street, so she was in and out. Family was always around,” she says. Her mother’s death from cancer in 1968 was a brutal shock, but was somewhat ameliorated by the live-in presence of her maternal grandmother, who handled all domestic duties. “My grandmother ironed everything that didn’t run away and hide,” Denise says with a fond laugh. “When she died [one week shy of her 98th birthday], I was telling my dad, ‘Well, you can forget about the ironed boxer shorts and pajamas because I don’t do that.’” After high school, Denise began a 27-year career with the FBI, mostly spent redacting Freedom of Information documents. Her father died in 1998 leaving her the sole inhabitant of the house, which she now shares with her rescue dog Simba. “I’m not wedded here, and I would go somewhere else,” she admits, “but I’ve never found any [other] place that I wanted to be.”