Home & Living

Everything You Need to Know About Building a Rain Garden

Locals let the depressed landscape areas soak up the storm.

When it rains, it pours. At least that’s the case when it comes to Tony Lehman’s front yard in Idlewylde, a neighborhood just south of Towson.

A video taken by the University of Maryland psychiatrist several years back shows what looks to be a river running several inches deep through his lawn and driveway. It’s all stormwater.

“It was really quite extreme,” says Lehman.

In 2016, he sought the help of a contractor to remedy the flooding, which he says was caused by an inadequate neighborhood storm-drainage system. That didn’t go to plan. But Lehman wouldn’t need to look very far, as it turned out, to find a plan B.

His son, Jackson, had just received his master’s degree in landscaping and architecture, and at his suggestion, the father and son made plans to install a rain garden in Lehman’s front yard.

So, what’s a rain garden?

Also known as biometric retention facilities, rain gardens are depressed landscape areas filled with native perennials, flowers, and shrubs. Typically built on natural slopes—as was the case with Lehman’s property—and planted using natural or engineered soil, these structures are designed to collect and treat excess stormwater runoff from compacted lawn areas and water-tight surfaces such as rooftops and walkways.

In Lehman’s case, the new addition would need to accommodate the runoff from his carport and driveway—as well as that of his neighbor’s—so he and Jackson had their work cut out for them.

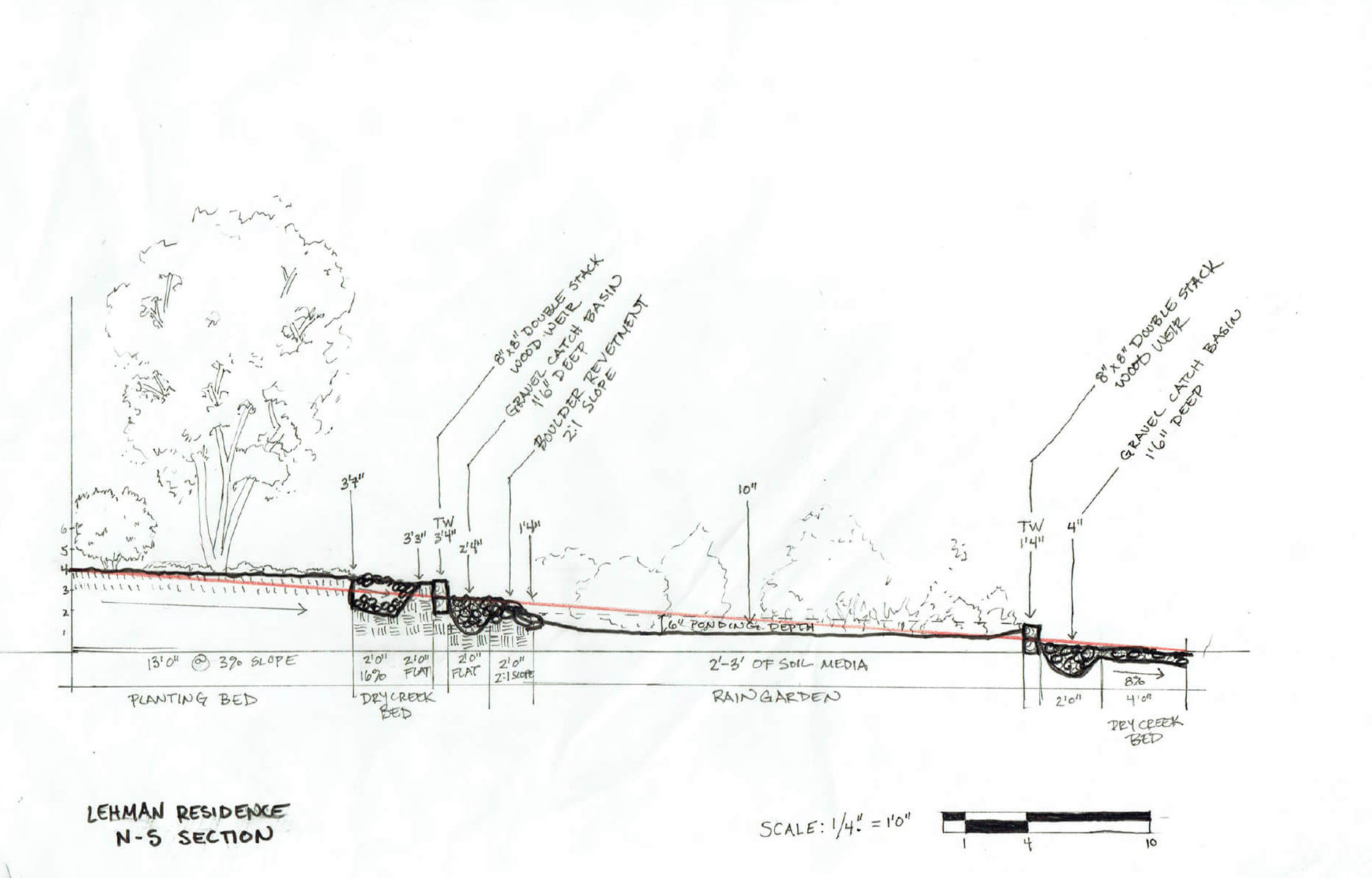

At the top of the garden, the pair installed two dry creek beds, which use rocks to drain excess stormwater flow. Inside, weirs, or low dams, were added, along with an absorbing mixture of clay, soil, and sand. With the addition of some native perennials and pollinators, the father-son rain garden project was complete.

And today? There’s a lot less flooding.

New bulbs have been planted in the yard for spring. And Lehman’s green thumb is, well, greener than ever, thanks to his son.

“I cringe a little bit now to think about some of the things I’ve done to plants be- fore I learned from him,” the dad says. “I feel very proud of him.”

While increasing in popularity because of ecological awareness, for now, rain gardens remain a rarity in this neck of the woods.

According to a survey by University of Maryland Extension service, a resource for farmers and gardeners, only 2.5 percent of state homeowners have one.

However, for those looking to fix their flooding, there are sources of information out there. Maryland Sea Grant Extension and Blue Water Baltimore can help with everything, from locating the best local contractors and specialists to finding an ideal place to put down a plot. But before you can do any serious dirt digging, you’ll need to grab a few tools to help you get started.

“One is a shovel,” says Tim McQuaid, the store manager and water garden manager at Valley View Farms, with a laugh. In addition to weed barrier fabric and stones for constructing dry riverbeds, McQuaid suggests corrugated piping or straight PVC pipe to act as the garden’s rain spouts. To amend the soil, he suggests mixing it with equal parts Leafgro compost.

Last but not least, get ready to pick out some plants—but, contrary to what you might guess, try not to choose too many tropicals.

For rain gardens, McQuaid suggests clumping plants, like Lobelia Cardinalis, which are native to Maryland.

“We are zone seven, and that’s important because, the further south you go, the higher the zone numbers are,” McQuaid says. “That means plants that are listed from zone seven and lower will survive in this environment.