Science & Technology

Palace Intrigue

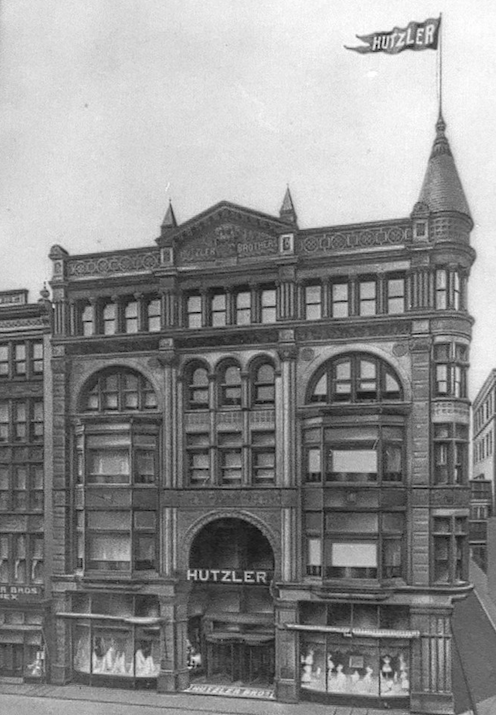

Long-shuttered Hutzler’s Department store is now home to 25 percent of global internet traffic.

In the halcyon 1950s, Hutzler’s department store employed 1,500 sales, office, and Colonial tea room dining staff. “Probably 2,000 during the holidays,” says Michael Lisicky, author of Hutzler’s: Where Baltimore Shops. “You went downtown to shop, lunch, see a show, go back, and shop again,” he says. “Lexington and Howard was the busiest intersection in the state.”

In a twist of fate hardly fathomable when the 140-year-old family business shuttered in 1989, that corner, specifically the former luncheonette basement of the old Hutzler Brothers Palace, is now home to one of the busiest “intersections” in the world. An estimated 25 percent of global internet traffic—including half of the emails, Amazon orders, Netflix streams, and iPhone downloads in the U.S.—pass through the stacks of underground AiNET servers there.

Many Baltimoreans know the backstory: In 1858, 23-year-old Abram Hutzler convinced his father, Moses, a German-Jewish peddler, to sign for credit so he could open a dry-goods store, which eventually set a record among American department stores for tenure at its original location.

Fewer know the current story: Deepak Jain, son of Indian immigrant parents, launched AiNET—originally a web-hosting company whose revenues now surpass $100 million—in his parents’ basement while attending Glenelg High School. (When he was a restless 6-year-old in a rural community without a lot of children nearby to play with, his parents had gotten him a Texas Instruments TI-99/4A home computer to keep him occupied.) By 1994, while in theory a sophomore Johns Hopkins University pre-med student, Jain’s business was growing fast enough that he could pay his own tuition.

Since then, AiNET, which employs two dozen workers on site, has expanded into a data center, cloud storage, IT services, and cyber-security business. Clients include federal contractors Jain can’t mention, as well as tenants at his telecom hotel such as Comcast and Verizon. In 2014, Jain bought the five-story Hutzler Brothers Palace on Howard and the adjoining seven-story building on Lexington known as One Market Center—where the Hutzlers tried and failed to reinvent themselves in 1985.

One of Jain’s related missions is Future Cities, an effort to bridge Baltimore’s digital divide by building a free Wi-Fi network across the city. Meanwhile, change has been percolating on the outskirts of the long desolate block. The Everyman and Hippodrome theaters and Bromo Arts District have sparked activity. Historic Lexington Market is also due for a $30-million-plus redesign.

For his part, Lisicky would like to see more AiNET initiatives similar to its collaboration with The Contemporary art museum in 2017, which opened the Hutzler Brothers Palace’s renown Art Deco doorways to the public for the first time in nearly three decades. The irony that what was once such a social hub now channels our digital communication—even a local text or email sent via the internet inevitably bounces through AiNET servers—isn’t lost on Lisicky. “There’s still a heartbeat in that building. It’s just digital and buried.”

As far back as 1941, Albert Hutzler, then company president, saw the handwriting on the wall. Long before his beloved department store came to its end, he had alerted a city planning conference at Hopkins that urban blight, unchecked, would lead to falling downtown real-estate values and transform Baltimore into a “ring city” with a shrinking core surrounded by thriving suburbs.

He added that such flight is not so much a problem for a merchant. “They go to the outlying communities and go on to build there,” said Hutzler, who would build stores in Towson, Catonsville, Dundalk, Glen Burnie, Woodlawn, Bel Air, and White Marsh. “It is the city itself that goes to pieces.”