Science & Technology

The Sea Also Rises

The Eastern Shore is already facing the dire consequences of global warming. Baltimore, Annapolis, and the rest of the region are on deck.

Ron Cassie - January 2015

The Hooper's Island Road Causeway at High Tide. —Greg Kahn

The first thing you notice is the standing water in the roadside gullies, even though it hasn’t rained in a week. Then, you notice the small houses and churches all teetering on concrete blocks or bricks four or five feet above the muddy, soft ground. But driving down Maryland Route 335 toward Hooper’s Island, it’s the trees that give you the deepest pause. Thousands of pine trees have been stripped bare of their needles, branches, and brown bark in this part of south Dorchester County. Ramrod straight, white as ghosts, the hollow trunks look like some kind of zombie deadwood, the staggering aftermath of an unfolding calamity.

Which, it turns out, is exactly what they are.

The land here is sinking beneath a fast rising Chesapeake Bay and the pine trees can’t survive the encroaching saltwater. Look closer, says Shawn Riley, a local waterman who makes his living harvesting oysters and blue crabs, and you can see that the process has been picking up speed. “Out on the boat, you’ll see trees leaning like this,” Riley says, holding his arm at a 45-degree angle. “There are tons of stumps, too, in the water. We have to maneuver around ’em.”

Riley, 53, grew up in the nearby small town of Crocheron and has lived on Hooper’s Island—the original home of the state’s century-old, family-owned Phillips Seafood—for 20-plus years. Technically, he lives in Hoopersville, the middle of Hooper’s string of three islands. Well, two islands now.

Or maybe one and a half.

The lower island, known as Applegarth, once a thriving village with its own post office, washed away decades ago. And Riley will tell you that Hoopersville, where it seems half of the remaining few dozen homes are for sale, probably isn’t long for this world, either. With rising sea levels accelerating erosion, Hooper’s Island is losing about two acres of land a month. “The street in front of my house is named Steamboat Wharf Road because there used to be a wharf down the way where the steamboats came in,” he says, pointing maybe two hundred yards away. Today, little remains of the old thriving wharf area, or of nearby Hickory Point. “That’s been [eroding] since I’ve been here.”

A Dorchester county pine tree withering in encroaching saltwater. —Greg Kahn

A dozen years ago, Hurricane Isabel swept the bay across the island, flooding and destroying Riley’s house, among many others. He says he considered leaving, but ultimately rebuilt with the help of a Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) grant and a low-interest loan. “They only offered the money if you built on the same site,” he says. “What else was I going to do?” His home now sits on a foundation that’s five cinderblocks high, but other issues press. The causeway from the upper island, known as Fishing Creek, to Hoopersville has begun flooding at high tide most of the year. A couple of years ago, when Riley needed to replace his old Chevy truck, he went with a bigger, taller Silverado, in large measure just to get home safely from work.

“I know those Arctic glaciers are melting and that water has to go somewhere,” Riley says, shrugging in his driveway on a recent, unseasonably warm afternoon. “I guess it’s coming here.”

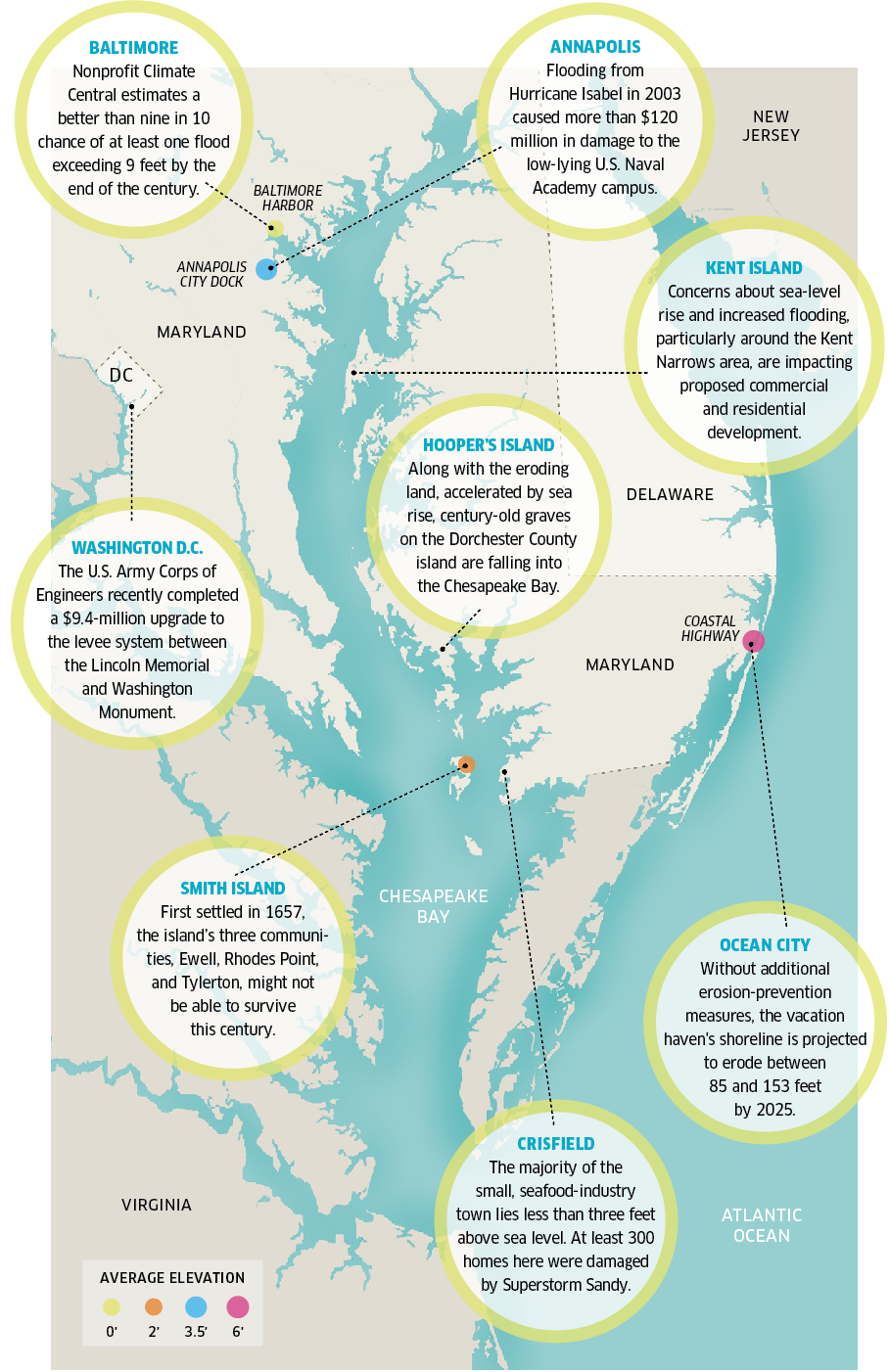

It is not just Maryland’s Eastern Shore islands that are in danger of disappearing beneath the surface because of global climate change and rising sea levels. In truth, 13 of the lower bay’s charted islands, many of them once inhabited, are already gone. Even more alarming are stories foretold by the interactive displays at the visitor center at the Blackwater National Wildlife Refuge in nearby Cambridge. Those models show that by the end of the century more than half of Dorchester County, the third-largest county in the state in terms of land area, will be under water. Of course, much of the Eastern Shore—most urgently, the lower counties of Dorchester, Wicomico, Somerset, and Worcester, which includes vacation haven Ocean City—is threatened by rising seas, erosion, tidal flooding, and storm surges. So, too, are western shore small towns in Anne Arundel, Harford, and eastern Baltimore counties.

The question really isn’t what will be lost anymore, but what we will decide to save.

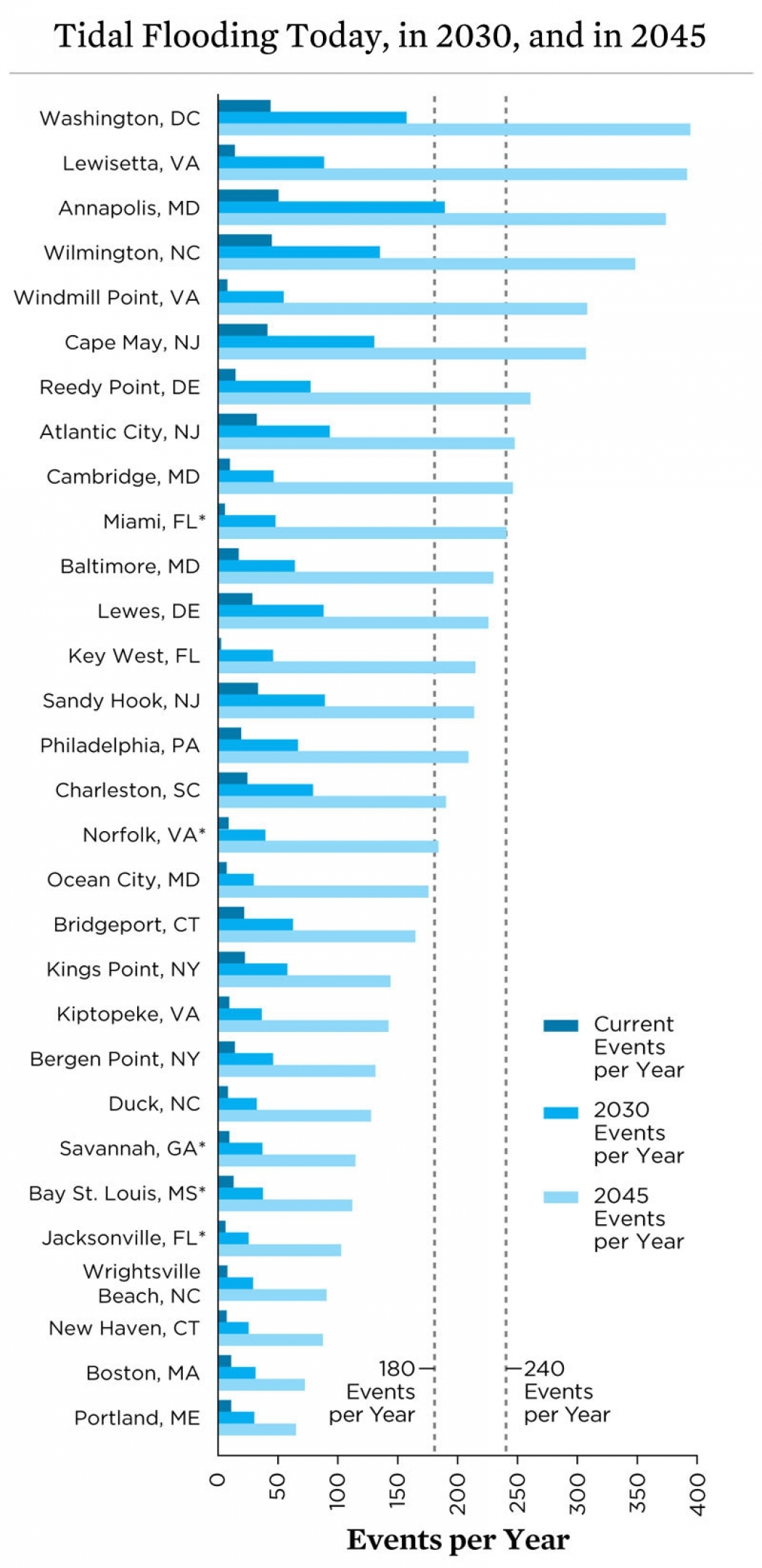

Due to the region’s geology and Atlantic Ocean currents, sea levels in the Chesapeake Bay are rising twice as fast as the global average and are projected to jump by as much as two feet in the next 35 years, and up to five feet or more by the end of the century. That leaves the state’s two largest cities on the bay vulnerable: Baltimore, with its iconic waterfront and port, and the state capital, Annapolis, with its historic city dock, will be challenged like never before in the coming decades by near constant flooding. So-called “nuisance flooding,” when storm drains get overwhelmed and water pools two or three feet deep, has already become more commonplace here than anywhere else in the country. Floods have already increased by more than 900 percent in both cities since 1960. Some projections call for 225 or more such floods a year for Baltimore and, essentially, daily inundation for Annapolis by 2045, according to a recent study based on National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration data.

“The question really isn’t what will be lost anymore,” says Jim Titus, a Maryland resident and leading sea-level-rise official at the Environmental Protection Agency, “but what we will decide to save.”

The last house on Holland Island, which succumbed in 2010. —David Harp

Annapolis, facing a growing crisis, is already one of cities most susceptible to flooding in the U.S. —Amy McGovern

The Inner Harbor, Fells Point, and the greater Baltimore Harbor area will be challenged by ever-stronger storm surges. —Baltimore City

Dundalk, in Eastern Baltimore County, is regularly forced to close roads today after storms. —John Long

Nothing in either the Climate Central or the Maryland Climate Change Commission report would come as a surprise to Mary McCoy, 60, who lives not on the

bay, but about 90 feet up from the Chester River outside the small Eastern Shore town of Centreville in Queen Anne’s County. McCoy readily recalls the

early morning hours of Sept. 19, 2003, when she and her husband decided to ride out Hurricane Isabel at home. When the winds finally quieted, they went

downstairs, hoping damage to the home, previously owned by her grandparents, was minimal. That is, until McCoy looked out her first-floor windows. “The

lawn was glistening in the dark,” she says. “The Chester River was in our front yard. We were moving the furniture as it began seeping through the

floorboards. When it receded, there were jellyfish and sticks and things all over the grass.”

Water entering the house was something that had never happened in the 80-year history of McCoy’s home. The ductwork in the basement needed to be replaced,

and soon she and her husband, like certainly thousands more in the coming years, had to start making decisions about a future that they hadn’t considered

previously. Initially, they discussed landscaping options, and then, later, sought a bid from a contractor to move the house further from the river.

Ultimately, moving the home, though probably necessary in the long run, was too costly at the time. McCoy had hoped to pass the family home onto her

younger cousins, but now she’s doubtful that will happen. “I ‘Googled’ and found a Maryland Department of Natural Resources map showing that the Chester

River will eventually be lapping at the foundations of my house,” she says.

Even more than the compelling data and science—the past year also recorded the warmest global temperatures since they began being measured in 1880—such

anecdotal evidence, says Mike Tidwell, director of the Chesapeake Climate Action Network, is at least helping Marylanders recognize that climate change is

undeniable. The change in sea level may be imperceptible year by year, but when a flood comes rushing in like never before, the message gets driven home,

he says. “It’s something that is difficult to wrap your mind around when scientists talk about projections in 2050 or the end of the century,” Tidwell

says. “But when you hear more people say, ‘That never happened before’—and we’re hearing a lot of ‘that never happened before’ these days—people begin to

connect the dots.”

One recent “never before” was Superstorm Sandy 26 months ago, which flooded the Inner Harbor, but mostly spared Baltimore City. Sandy walloped much of the

Eastern Shore, including Ocean City and Salisbury, where the mayor instituted a civil emergency and a curfew during the storm. Sandy hit Crisfield, a town

of 2,726 and the self-proclaimed “crab capital of the world,” very hard, with waves of white caps literally pouring into the heart of downtown and driving

caskets up from their graves. At the Captain’s Carry Out on Main Street, which remained without power for days, the Little Annemessex River, at the mouth

of the Tangier Sound, came rolling in halfway up the counter.

With devastation to Long Island, NY, and the Jersey Shore grabbing the national attention, the fallout in Crisfield has been widely overlooked. The storm

displaced hundreds of local families, some of whom never returned home, and, eventually, residents there began thinking about climate change in relation to

the town’s precarious location on the Delmarva Peninsula. “It made believers out of everyone,” says former mayor Percy Purnell, whose own property, as far

away from the shoreline as you can get in Crisfield, was inundated with two feet of water. “There’s no question sea levels are rising, in my mind. Every

time you rebuild a dock here, it has to be built two or three feet higher than it used to be when I was a kid growing up.” The town has received money

since Sandy from the Maryland Emergency Management Agency to install tidal gates in the town’s storm drains and is working with the U.S. Army Corps of

Engineers to drop a series of breakwaters near the town’s shoreline. Two nearby barrier islands need be rebuilt to protect Crisfield as well.

The town is also close to passing legislation requiring that the first floor of all new structures be elevated above ground. New homes receiving FEMA money

have been elevated four to seven feet off the ground, in accordance with their regulations.

“Sandy completely changed the community’s consciousness around climate change,” says James Lane, a Crisfield minister and community historian. “People

recognize that we are, and will be, consistently challenged by rising sea levels now. And we will have hard choices to make. We lost a lot of people who

moved after Sandy, elderly people who didn’t feel like they could deal with something like that again, as well as young families and newer residents, who

don’t want to face these issues their whole lives. So, what do we do? Abandon and move? Those people become climate-change gypsies, as I call them, or

refugees,” Lane continues. “Then again, what about the people who can’t leave because they’re poor and have no place to go? We have a lot folks who make a

living on the water or in the maritime industry, struggling to get by as it is.”

In many ways, Crisfield, in making decisions where and how to rebuild, is on the forefront of a complicated, multi-pronged process that will play out over

and over again across low-lying areas of the state.

More than 40 percent of the homes and assets of Somerset and Worcester counties lie below the five-foot high-tide line, and more than half of Dorchester

County lies below 4.9 feet above sea level. In Baltimore City, low-lying areas include dense commercial and residential districts such as the Port of

Baltimore, Canton, and Fells Point, where most residents and business owners have already become dedicated sandbaggers in the wake of various hurricanes

and tropical storms. Models show that the whole Inner Harbor would be at risk during 8-foot storm surges, which are projected to be a fairly common event

by the end of the century.

Other populated areas in Baltimore County, such as Middle River, Bowleys Quarter, Dundalk, and Edgemere, which already face severe flooding problems, will

see an increase in storm surges, too. In Anne Arundel County, Glen Burnie is expected to see greater flooding and some residents of Shady Side and Deale

could find themselves underwater by the end of the century. In Harford County, places like Joppatowne and Havre de Grace will be in greater harm’s way.

CHESAPEAKE BAY FACTS MAP

Led by the University of Maryland Center for Environmental Science, the most recent state report recommends Maryland plan for up to two feet of sea-level rise by 2050, highlighting the need to build adaptation into the state’s natural and built environments. The study’s assessment only worsens moving forward, with a “best estimate” of sea-level rise of 3.7 feet by 2100 and the possibility of a 5.7-foot sea-level rise by the end of century. With 3,100 miles of tidal shoreline and 265,000 acres of rural and urban land situated less than five feet above the high-tide line, much of the state faces a significant increase in flooding in the years ahead.

Of course, Queen Anne’s County, especially vulnerable near Kent Narrows just over the Bay Bridge; Talbot County, which includes scenic St. Michaels and

Tilghman Island; and Kent, St. Mary’s, and Calvert counties; also have a lot of hand-wringing to do about where and how to protect shoreline,

infrastructure, and homes. (On a related note, consider that Garrett County in Western Maryland was a center of the U.S. maple syrup industry before rising

temperatures pushed the industry farther north.)

In fact, the mantra often heard in response to climate change and sea-level rise from federal, state, and local officials and planners these days is not

prevention, but adaptation. The choices are generally presented as “defend, retreat, or accommodate.” The euphemism “managed retreat”—a mixture of the

three, but not a phrase many politicians will want to be associated with—has also been thrown around among planners and climate scientists.

In general, sea-level rise planning efforts for most counties and municipalities largely remain in the early assessment stages. Considered at the

forefront, however, the Baltimore City Department of Planning has created a new initiative: the Disaster Preparedness and Planning Project (DP3), which is

addressing, among other issues, existing flood problems and expected higher sea levels. The city has already set new building guidelines to offset higher

sea levels, including lifting the base elevation of new structures from one to two feet above the 500-year tidal flood plain. The DP3 also recently

completed a report identifying vulnerable assets and critical facilities.

At the same time, Baltimore City is considering other projected climate-change and natural hazards, including more frequent and more intense precipitation

episodes, as well as droughts and potentially deadly heat waves. According to a 2013 DP3 report, average air temperatures are expected to rise by 12

degrees in Baltimore by 2100, at which point the city will feel more like New Orleans. “It gets overshadowed by the attention on sea-level rise, but we

have ‘hot spots’ in many parts of the city, like in East and West Baltimore, that are of an immediate concern, especially for senior citizens and children

in those neighborhoods,” says Kristin Baja, the city’s climate change czar within the Office of Sustainability. “Heat waves like we’ve experienced in the

past and other cities have experienced can be life and death situations.”

While the powers that be in D.C. work to protect the national monuments on the Mall and New York City plans the initial construction of “The Big U,” a

10-mile, $335-million fortress of berms and moveable walls to safeguard lower and midtown Manhattan, compromises on the Eastern Shore (as the minister from

Crisfield referenced) are already underway.

Several months after Sandy, state officials offered controversial buyouts to a number of homeowners on Smith Island, which is eroding and sinking into the

bay. The buyouts seemed more practical than reinvesting in an island with 276 residents that, in the long run, appears doomed. On Kent Island, Gov. Martin

O’Malley and the state Board of Public Works have sparred with local officials and developers over the addition of a big condominium project because of the potential impact on what they consider an already at-risk flood area and over-burdened environment.

Following an executive order by O’Malley in 2012, two months after Sandy, new formal guidelines for state construction projects were published last year,

recommending that future state and/or other major infrastructure projects should avoid, wherever possible, areas likely to be inundated by sea-level rise

in the next 50 years. By setting the guidelines, says Zöe Johnson, director of resiliency planning and policy for the Maryland Department of Natural

Resources, the state is trying to lead the way for counties and municipal government planning. She also notes that Maryland needs to keep working on

maintaining and building natural protections against sea-level rise, such as wetlands barrier islands, because they remain critical to protecting

shorelines. "You can look at the Gulf of Mexico,” she says. “You lose wetlands and you have Hurricane Katrina.”

Along with Baltimore City, Johnson adds that Annapolis and Anne Arundel County have been working with the state in developing flood mapping, planning, and

mitigation efforts for the past several years. “We really want to work with every jurisdiction and provide all the technical assistance and financial

assistance that we can,” Johnson says. “We are supporting them as much as we can, but we really can’t do it for them. In the end, it’s going to be up to

each county and community.”

Tidwell, of the Chesapeake Climate Action Network, believes that recent polls indicating support for additional clean-energy goals in Maryland at least

offer hope for the future. He’s also pleased the state is at the forefront of reducing carbon emissions, noting that outgoing Gov. O’Malley made dealing

with climate change a priority, signing legislation to reduce greenhouse-gas emissions by 25 percent by 2020. Now, Tidwell and his organization are trying

to raise the bar on clean energy, pushing a new goal of 40 percent by 2025.

Even with new Republican Governor Larry Hogan, who has criticized the state’s sustainability and alternative-energy goals, taking office, Tidwell believes

there’s opportunity to make progress. “[Former Republican Governor] Bob Ehrlich actually signed the state’s first greenhouse gas emissions bill, the

Maryland Healthy Air Act, and one of the original clean-electricity mandates into law,” he says. If the state legislature is willing to act, he says,

legislation can get passed. “If you walk around the state house in Annapolis, about 90 percent of the pictures from around the state include water,”

Tidwell continues. “Maryland is a water state, and it only makes sense that we should be leaders in dealing with climate change and sea-level rise.”

THIS GRAPH CHARTS THE PROJECTED FREQUENCY OF TIDAL FLOODING IN THE NEXT 15 AND 30 YEARS.

U.S. coastal communities, including those in Maryland listed to the right, are already dealing with more tidal-flooding episodes than in the past. As climate change pushes sea levels higher — through melting glacial ice and rising ocean temperatures, which expand water volume — flooding over the next 15 and 30 years is projected to occur much more frequently. With rising sea levels also creating higher tides and greater storm surges, flooding will reach previously “safe” ground as well, and cause more disruption, particularly along the East Coast and Chesapeake Bay region, where sea levels are rising twice as fast as the global average.

But so much climate change and sea-level rise is “baked into the cake” at this point, says Boesch, that in reality, any action taken in the next 40 years

likely won’t make any major impact in Maryland until the next century. “There’s little we can do now to reduce sea-level rise by the middle of the century,

but we can potentially help by stabilizing global temperatures and sea-levels by the end of the century, for the next century,” Boesch says. “I can tell

you one anecdote about this that’s funny but also a little sad at the same time,” he continues. “There’s an elderly couple on the Eastern Shore that I

visit from time to time. They used to always ask me, ‘How much longer is our house safe?’ Well, the last time I saw them, they didn’t ask about the house.

They told me they’re going to be buried in Oxford, and they wanted to know if their graves would be safe. I told them, ‘Probably until the end of the

century, I can’t make any promises after that.’”

Unfortunately, this means that much of what we consider quintessentially Maryland on the Eastern Shore, including significant state natural treasures, such

as the Blackwater National Wildlife Refuge and the Assateague Island National Seashore will be lost. Historic landmarks, too, such as Harriet Tubman’s

birthplace and the museum planned in her honor are at tremendous risk.

In Anne Arundel County alone, 422 archaeological sites, including four historic lighthouses, as well as historic downtown Annapolis and its centuries-old

city dock are at risk in the next decades. “A few of these sites are 3,000 years old, Native American sites, that will inundated by flooding over next 100

years,” says county contract archeologist Stephanie Sperling, who participated in a two-year study of the county’s threatened assets. “A huge part of our

cultural legacy, will just wash away.”

Historically, of course, Marylanders have long had to struggle with rising water levels and erosion. Before the 20th century, this was largely due to the

slow subsidence of the land along the Chesapeake and Atlantic. With climate change accelerating the process since the Industrial Revolution, the problem is

taking on a more serious existential threat for many Marylanders.

On Smith Island, where the official Maryland state dessert, Smith Island cake, is still made by local women at the Smith Island Baking Company right off

the dock, the looming threat to home, community, and a way of life, is never far from the minds of the remaining residents. A 45-minute boat ride from

Crisfield, the island remains happily isolated from the harried pace of modern life and people here like the sunsets. It’s the last of Maryland’s inhabited

lower bay islands not accessible by car.

The post office is only open four hours a day and the public school, with 11 students, is the smallest in the state. Home to watermen, a few retired folks,

and a couple of bed-and-breakfasts mostly catering to summer visitors, the island rallied after the state offered buyouts, turning them down and instead

organizing a group called Smith Island United to fight for grants to build badly needed sea walls and jetties to slow down erosion, and, at least, delay

what is most likely its fate.

Erin Pruitt, who grew up on nearby Tangier Island, on the Virginia side of the bay, is one of the bakers at the Smith Island Baking Company, and like all

the women working in this friendly atmosphere, she doesn’t want to leave. Only 26, she lived in Ocean City for a while before falling in love with a young

man and moving to Smith Island. She admits occasionally missing the convenience of living inland, but she cherishes the slower pace and strong sense of

community here.

“It’s the people here I love more than anything else, and if the island ever disappears, the culture and community will, too,” she says. “And that’s what I

grew up with.”

Lively and thoughtful, a white apron tied around her waist as she removes the nine-layer chocolate and coconut cakes from the baking racks, Pruitt pauses

and looks down for a moment. “People ask, from time to time, ‘Do you think when you have kids and grandchildren that Smith Island will still be here?’” she

says. “‘I hope so,’ I say.

“But the truth is, and the reason it takes me a while to answer that question,” she continues, “is that I don’t want to think about it. That’s the harsh

reality.”

With 3,190 miles of shoreline and 265,000

acres of rural and urban land situated less than five feet above the high-tide line, Maryland, along with Louisiana and Florida, is among the states most

vulnerable to sea-level rise. With slowly sinking land around the Chesapeake (still settling from the last Ice Age, ironically enough), rising seas will

eventually necessitate the need for revised or completely neBy our estimate, we should prepare for a sea level that’s going to come up to our knees by 2050 and then chest-high by the end of the century.

[In terms of climate change], Sandy made believers out of everyone.

TWO feet high and rising

You can look at the Gulf of Mexico. You lose wetlands and you have Hurricane Katrina.

High Water Mark

Courtesy of Union of Concerned Scientists