Sports

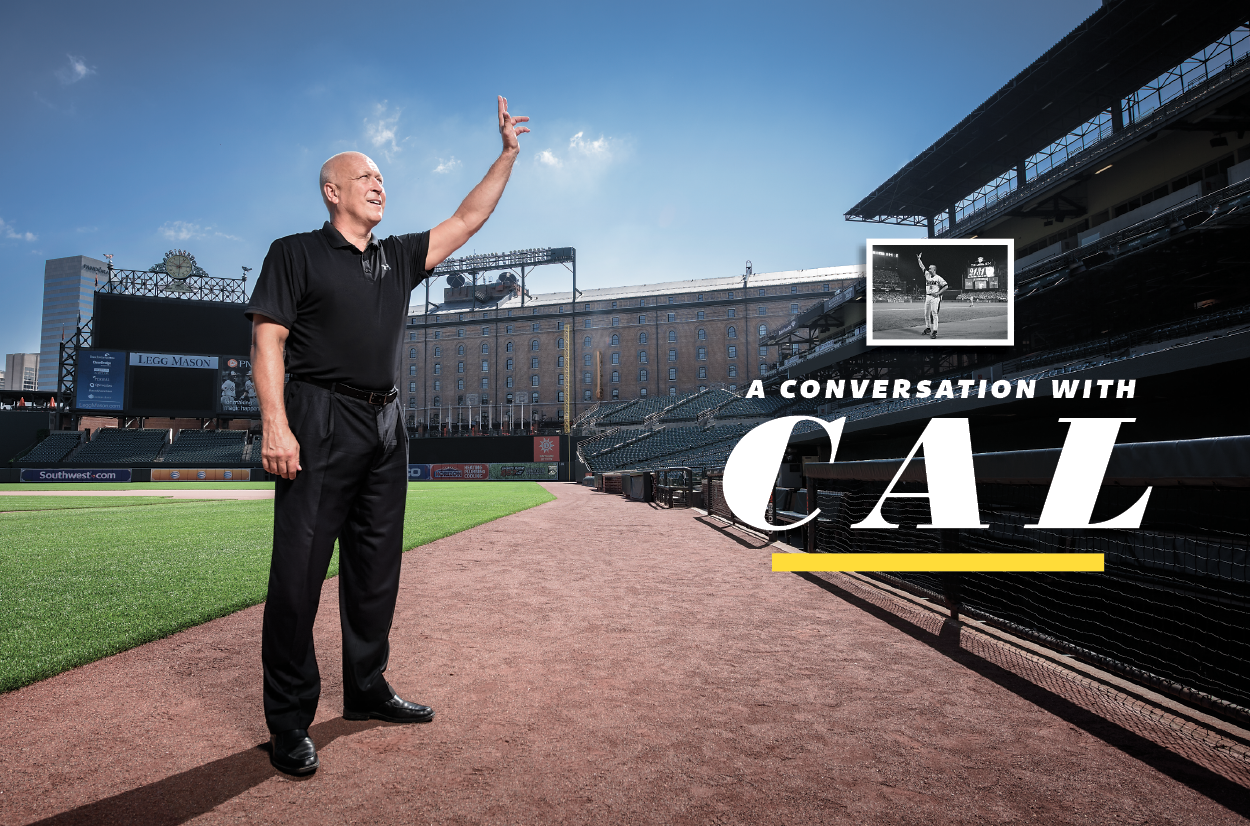

A Conversation with Cal

We talk to the Iron Man about what his record-breaking feat feels like 20 years later.

Cal Ripken, Jr. woke up with a fever. He figured it was due to the exhaustion of the past couple of weeks. His mind had been turned on a lot and he was spending night after night at the ballpark to sign autographs—sometimes until 3 a.m.—long after the media had packed away their cameras.

That day, the media would be there in droves. After all, it was September 6, 1995, the day he was set to break Lou Gehrig’s record of consecutive games played in a Major League Baseball uniform. But before the spotlight turned on, it was time to get his daughter, Rachel, to her first day of pre-first at St. Paul’s School for Girls.

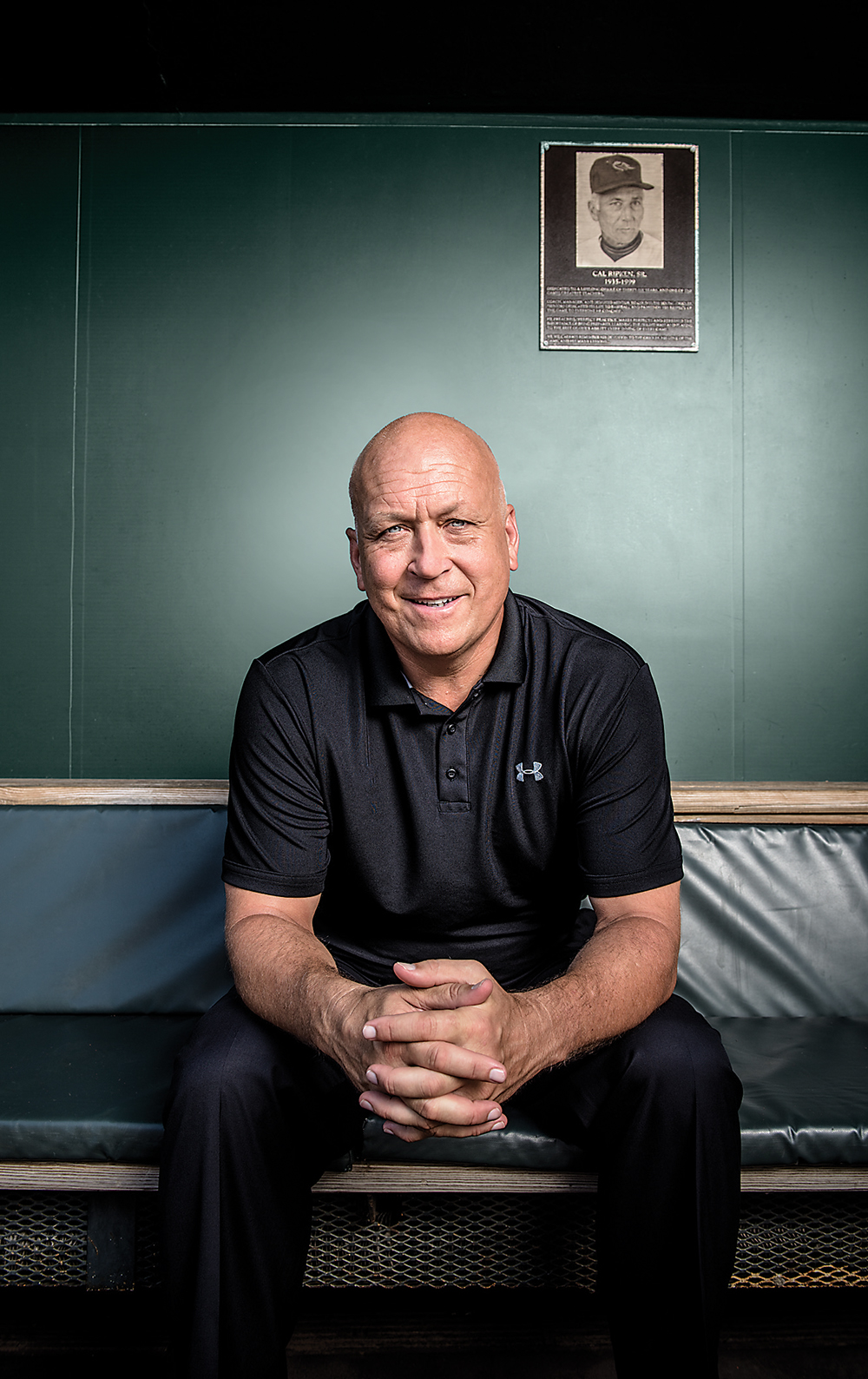

“I took her to school, then came back home to try and get some sleep. I didn’t do too well at that,” says Cal, as he sits in the clubhouse of Oriole Park at Camden Yards, leaning back with his palm resting under his chin, 20 years later. “Sleep was a little bit hard for me that last week.”

In fact, he admits he was emotional long before the day the warehouse banner numbers flipped to 2131. For weeks, the Orioles events crew had made it a daily routine to flip the number and play the music in the middle of the fifth, when the game became official.

“The first time I was at shortstop and I heard the music—I think it was John Tesh—and the number changed, it gave me goose bumps,” he says. “Then everyone on the field and in the stands just became conditioned to look at that warehouse in the fifth.”

Like those weeks leading up to it, the day of September 6 flew by. “Before I knew it, I was back at the ballpark,” he says. “We did our best to keep the media out of the locker room—I didn’t want my teammates to be impacted—but I think the team was really excited. Sure, there was a little ribbing in the locker room. I don’t remember who the culprits were, but I knew I felt it and was sensitive to it.”

When he needed a break, Cal said his “go-to guy” was longtime trainer Richie Bancells, whom he’d known since 1978. “I never wanted to be in the training room for treatment, but I wanted to be there to talk to Richie. He was always there for me.”

As game-time approached, the park took on a playoff atmosphere, as nearly 50,000 fans filed in, camera flashbulbs danced around the crowd, and President Clinton took his seat in the skybox (with Secret Service agents perched on the stadium rooftop).

By the time the ceremonious middle-of-the-fifth came around, the O’s were already beating the California Angels 2-0 (including a kismet dinger by Cal in the fourth, which the President called alongside Jon Miller in the booth). As had happened every game for weeks, the music swelled, the crowd’s cheers were deafening, and the banner unfurled from “0” to “1.” Hundreds of black and orange balloons lilted through the air and what followed might be the longest standing ovation for any athlete in history. Twenty-two minutes, to be exact.

“The first time I was at shortstop and heard the music, it gave me goose bumps.”

“It was really, really long,” Cal says with a laugh. “I was embarrassed because you don’t stop a game in the middle. Pitchers are warming up; players have a rhythm. So I was like, ‘I’ll celebrate afterward as much as you guys want, but let’s get this game going.’”

But his teammates, namely Rafael Palmeiro and Bobby Bonilla, weren’t having it, and after Cal did a couple of hat tips to the crowd, the pair physically pushed him out of the dugout and onto the field for his famed lap. As the Orioles event staff scrambled to find a song to play (they went with Whitney Houston’s “One Moment in Time”), Ripken still wasn’t too enthused.

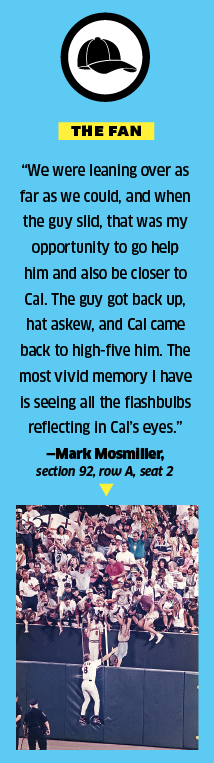

“At first I was thinking, ‘Let’s get this game going,’ but then, as I’m going around, I’m like ‘Wow, this is really cool,’” he says, his voice gaining speed, as he stands in front of an illustration of the stadium. “I’m recognizing a lot of people, not just faces but names, recognizing more people, oh man that dude just fell down, and then all of a sudden about here [he gestures toward the outfield bleachers], I don’t care if we start this game ever again. I got slower and slower as I came down this way. It was almost like—I couldn’t care less about starting the game again. A celebration of 50,000 turned one-on-one.”

Certain moments—like the one he mentioned of the fan reaching out so far that he fell from the bleachers—stick out more than others. He remembers seeing his agent, Ron Shapiro, by the third baseline. And noticing a sign that read “The House That Cal Built.” Then there was an exchange with Angels Hall of Famer Rod Carew, whom Cal had long admired.

“I wish I could tell you what words were said,” he says of the moment with Carew. “I just remember being blown away by the fact that it even happened.”

And, of course, once he rounded back to home, he remembers hugging and kissing his wife, Kelly, and his kids, Ryan, 2, and Rachel, 5, who said “Ew!” when she kissed her dad’s sweaty forehead. He took off his jersey to reveal a homemade T-shirt that said “2,130+ Hugs and Kisses for Daddy.” Then he looked up to the skybox, where his parents, Cal Sr. and Vi, stood, clapping proudly.

“There was one moment when I caught Dad’s eye. Nothing was said, but 1,000 bits of information were traveling back and forth between us.”

Like many nights before, Cal stayed at the ballpark long after the game ended, this time doing an interview with Bob Costas in the weight room around 2:30 a.m. The next day, thankfully, the O’s had off and “once the adrenaline slipped away,” he, more or less, caught up on sleep.

“Man, I’ve been out of the game for a long time.”

The team then traveled to Cleveland, where Cal was excited to see his former teammate and good friend Eddie Murray. Instead of the managers trading lineup cards before the game—as is typical—Cal and Murray did the honors. Cal got an extra firm “atta boy” handshake from the crew chief and a standing ovation in Jacobs Field.

“After that, for the most part, things kind of went back to normal,” he says. “The playoffs started the way they always had.”

Cal Ripken, Jr. is doing math in his head. “So, my last year as a player was 2001, so now we’re in 2015 and now I’m thinking, ‘Man, I’ve been out of the game for a long time,’” he says, smiling and shaking his head.

As with any anniversary, some moments feel like yesterday, he explains, while others seem more like a lifetime ago. He admits that he has a box of mementos hidden away somewhere (“I’m a hoarder”), but that he hasn’t looked at it in a while.

He belly laughs when asked if he ever got sick of himself—the Streak Week parades, the milk ads, the Iron Man nickname, the September 1995 cover of this magazine.

“You know, you have to maintain perspective,” he says. “You’re a sportsman, not an entertainer. The people that look at themselves as a form of entertainment might get sick of themselves after a while. But that particular time didn’t make my head bigger or make me think I’m more important.”

In true Cal form, he begins to divert his answer away from himself.

“It was more about accepting what the meaning was. This was a time, after the ’94 labor issues, when people weren’t happy with baseball. Comparing the streak back to an era of Lou Gehrig, an era of Ken Burns-like baseball, you got this nostalgic feeling. That’s how I understood it and how I wrapped by head around it.”

Something else he took away from the 2131 era really had nothing to do with baseball. It was this idea that, suddenly, streaks were cool.

“Perfect attendance in school—which I never had, by the way—was a big source of pride for kids,” he says. “I was hearing about nurses or teachers or people working in plants having never missed a day. And then there was [umpire attendant] Ernie Tyler, who only ended his streak to come to my Hall of Fame ceremony, which he was so excited about.”

In Cal’s mind, his 2007 Hall of Fame induction and the 1983 World Series stand up there with 2131. At the Hall of Fame ceremony, there was a sea of orange and number eights staring back at him. To try and repay the fans, he remembers driving in a van through Cooperstown, popping out to surprise folks in Orioles gear, shaking their hands, and jumping back in.

“I just remember being blown away by the fact that it even happened.”

He comes back to the fans a lot. Like it was just last season, he recounts a game at Memorial Stadium in 1989 when he was ejected in the first inning for arguing balls and strikes.

“I heard later that a family traveled [to see the game]. They were sitting in the second or third row,” he says. “After I got ejected, they said the kids cried the whole rest of the game. Maybe I’m uber-sensitive, but those kind of stories chew me up.” (At least the story has a happy ending. Apparently, a nearby season-ticket holder gave them tickets for the next day.)

He says this was a lesson that his dad taught him, that it is your responsibility to your teammates and your responsibility to the fans to come out each and every day.

“I’ve gotten asked before, ‘Does it make you feel bad that people will only remember you from the streak, not the great player you were?’ And I’ve never understood that,” he says. “It’s not like I came to the big leagues telling Earl Weaver, ‘You’ve got to play me.’ I earned the place to play. The manager has the ultimate choice, and if he chooses you, you always play.”

He takes a long pause and admits, with a slight glint in his blue eyes, that a recent Father’s Day had him thinking a lot about his dad, who died in 1999.

“Dad was funny. He would always say, ‘You can’t play tomorrow’s game. You can’t replay yesterday’s game. You might as well play the game today.’”

The 2131 Scrapbook

Personal accounts from behind-the-scenes on September 6, 1995.