Sports

Civil War

Returning to Baltimore this month, the Army-Navy game is always an unforgettable experience.

It’s not the oldest rivalry in college football, nor does it decide the winner of a top conference. It doesn’t have a colorful nickname like “The Iron Bowl” or feature players headed to the NFL immediately afterward. Army-Navy isn’t a lot of things that big-time college football has become, which helps make it what it is: the best rivalry in all of American sports. And this year it’s coming to Baltimore. From the pre-game pageantry, when the immaculately uniformed corps of cadets and brigade of midshipmen march onto the field in tight formation, to the post-game moments, when both teams stand at attention, sweating and shivering together during the playing of each school’s alma mater—the 70,000-plus at M&T Bank Stadium and millions more watching on TV around the globe will be treated to a spectacle unlike any other.

“It’s about recognizing those who have served, and those who are about to serve,” says Maryland Sports executive director Terry Hasseltine, who helped bring the game here. “If you are a sports fan, this is one that has to be on your bucket list.”

But peel away the pomp and circumstance and, at its core, Army-Navy (never Navy-Army) is a competitive football game. For the seniors, all but the rare exception, it’s their last. Military service, not the glamour and riches of professional football, await them when the clock hits zero.

“It was so bittersweet,” Mount Airy native and former Midshipmen receiver Billy Hubbard says of his last collegiate football game, Navy’s 30-28 victory in 2000. “I remember walking into the locker room and taking off my shoulder pads thinking, ‘I will never do that again.’ Everybody knows you’re not going to play sports forever, but you all know you’re going onto the battlefield together.”

Those words have grave meaning. Since 2001, five Navy football players and 95 U.S. Military Academy graduates have been killed in combat. They’re why, when the whistle blows, players offer a fallen opponent a hand up, why unsportsmanlike conduct penalties are unheard of, why on the second Saturday in December this game stands alone.

And why Hall of Fame quarterback Roger Staubach, who won the Heisman Trophy at Navy in 1963, once said, “This is not a regular game, and everyone involved knows it.”

Army and Navy first squared off on the gridiron in 1890 at “The Plain” in West Point, NY. Navy won that game 24-0, while Army took the rematch 32-16 the next year in Annapolis. The rivalry, which has been unusually streaky over the years—Navy holds a 58-49-7 overall advantage based on its current 12-game winning streak—was on.

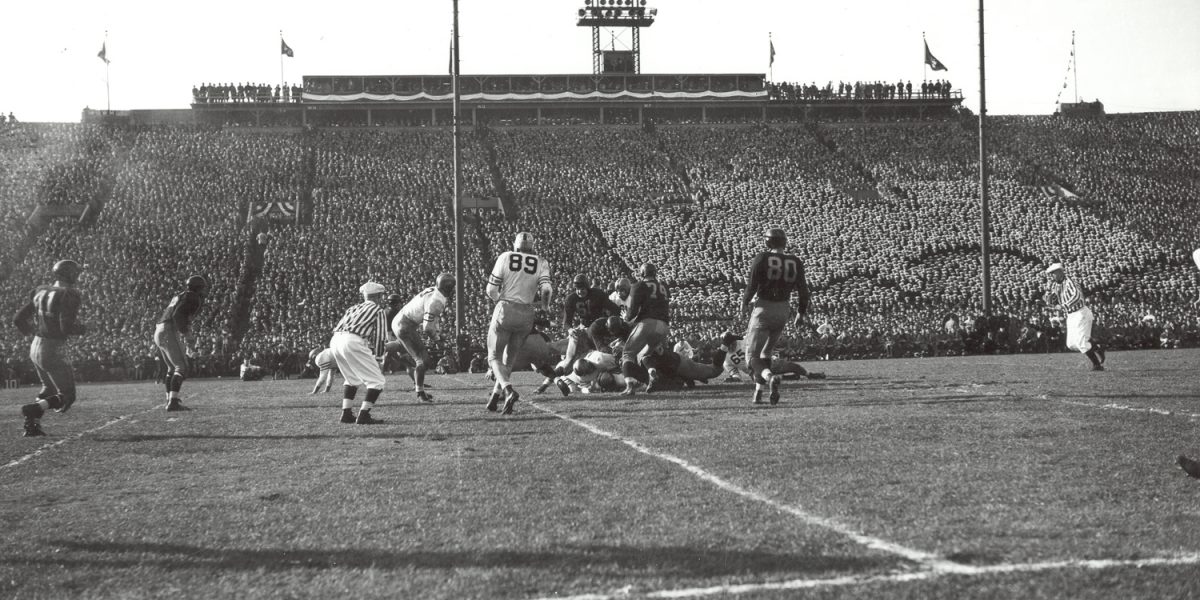

It first came to Baltimore in 1924, when Army won 12-0 at Municipal Stadium, as Memorial Stadium was once called. In 1944 it returned, this time, under the cloud of war. Undefeated Army entered the game ranked No. 1 in the country. Navy was No. 2.

“It was the biggest game of World War II,” says Randy Roberts, author of A Team for America: The Army-Navy Game That Rallied a Nation. “Here is a time when Army was never more present in the thinking of America. We’re talking about the time between D-Day and the Battle of the Bulge. You have a football team that represents West Point and by extension the army rolling through its schedule kind of like Patton’s tanks through France.”

Historically (and still) staged in Philadelphia, the Army-Navy games were almost canceled during the war, according to Roberts, a Purdue University history professor. With travel restrictions for military personnel, the series moved onto the schools’ respective campuses for the 1942 and 1943 games, but those venues ultimately proved inadequate. By 1944, “these were the best two teams in the nation, so considerable pressure was brought on the government to change the venue [to a larger stadium],” Roberts says. Since the game was supposed to be played in Annapolis, it went to Baltimore.

“As a plebe . . . you’re always having to yell, ‘Go Navy, beat Army!’”

Army, which had legends Doc Blanchard and Glenn Davis, known respectively as “Mr. Inside” and “Mr. Outside” because of their tandem running prowesses, won 23-7. The teams remained relevant nationally through the ’50s and into the ’60s before the changing nature of collegiate athletics pushed them to the fringe of big-time NCAA football.

Still, the game remains critically important to the academies—the entire brigade of midshipmen and corps of cadets attend—their alums, and for three hours on a usually frigid afternoon, to fans of the purest version of college football.

“The Army-Navy game is the culmination of the entire first semester,” says Christopher Barker, a 2000 Naval Academy grad. He didn’t play football, but the Davidsonville resident tailgates before most home games. “As a plebe [a freshman], in particular, that’s what’s drilled into you from day one. As you’re squaring your corners [walking in the hallways], you’re always having to yell, ‘Go Navy, beat Army!’”

Barker recalls attending his first game as a plebe at the old Veterans Stadium in Philadelphia. “Pouring rain, it was miserable, it was cold. We ended up losing, and it was such a morale hit,” he says. “Guys were crying because they thought, ‘Man, this was important.’ It’s a rite of passage.”

Then a senior at Linganore High School, Mount Airy’s Hubbard was also at the Vet that day, on a recruiting visit. His father had played sprint football (172-pound weight limit) at Navy, and his uncle played lacrosse at the academy. Four years later, after breaking into the starting Navy lineup as a senior, he played his final game a short drive east on I-70 from his childhood home.

“I kind of sensed when we played that neutral-site game in Baltimore that the fans were more for Navy,” he says. “I felt like it was our home turf. I had one catch in that game. There was a third and long, and I ended up catching a pass, but we didn’t get the first down. It was a meaningless play, but it felt like the most important play of my life.”

Navy’s close win that day salvaged a disappointing 1-10 season. At least the “one” was the one that mattered most. For 364 days, they held bragging rights over their rivals.

The following year, in 2001, Army beat Navy by nine points, the culmination of a 0-10 season for the Midshipmen and a low point for the program before its subsequent resurgence under coaches Paul Johnson, now at Georgia Tech, and Ken Niumatalolo. (Navy even managed to knock off Notre Dame three times in four tries between 2007-2010.)

“I remember Army’s crowd chanting ‘Defeated!’” says Ralph Henry, an Essex native who played for Navy from 1999 to 2003. “I won’t ever forget being on the sideline saying to myself, ‘We will never lose to these guys again.’ Twelve years later, we haven’t. [The next season] when I got the opportunity to beat them and actually have some impact on the game, there was no better feeling,” the 6-foot-2, 280-pound former defensive end continues. “Just to watch the Midshipmen in the stands jumping around, it was awesome.”

Included in Navy’s recent streak is last year’s 34-7 win over Army, and a 38-3 victory in 2007 at M&T Bank Stadium, the last time the game was played in Baltimore.

Some 15 cities fromthroughout the country submitted proposals to host the game when the academies put it up for bid in the late 2000s. In 2009, Baltimore was awarded this year’s game along with the 2016 game. Next year, and in 2017, it will be played in its traditional home, Philadelphia.

“Baltimore showed that they could meet the fiscal expectations, the community expectations, the facility expectations,” says Chet Gladchuk, Navy’s director of athletics. “The Ravens were involved, the mayor [then Sheila Dixon] was involved, the governor [Martin O’Malley] was involved.”

Why did a single football game garner such attention from so many important people and organizations? Terry Hasseltine can give you 25 million reasons.

“Army-Navy is not just a one-day football game, it’s three to four days of other activities,” he says. “We’re talking two weeks from the Christmas holiday, two weeks after the Thanksgiving holiday, during a time when the city’s pretty quiet. You have the gala [at the Baltimore Convention Center] the night before, you have alumni groups having parties. The estimation is it’s going to be between a $25 and $30 million impact. That includes a full dynamic of out-of-town spending, hospitality spending, transportation spending, ticket sales, concessions, parking.”

“We [at Navy] thought that practice was the best part of the day, because school is so tough.”

A civic-pride factor is at play as well as an afternoon in the national spotlight. The game attracts military VIPs, political dignitaries (even the President, occasionally) and the eyeballs of thirsty college football fans watching at home. Since moving to the week after the sport’s conference championships a half-dozen years ago, it’s generally the lone game on the schedule, and Army-Navy television ratings have nearly doubled, drawing 6.2 million viewers in 2013—the highest-rated game between the teams since 1999.

“The week leading up to the game, the visibility is extraordinary,” Gladchuk says. “It’s as visible in its promotion as a national championship game and, of course, it culminates with the game. We sold every ticket that we had back in July.”

Demond Brown might need to track down a few for his friends and family. The junior slot back attended Old Mill High School in Millersville. He played special teams during his first Army-Navy game, and last year got on the field for a number of offensive plays. With the game coming to his backyard, he hopes to have a greater impact on December 13.

“It’s always a special feeling when I play in Baltimore,” he says. “This will be a big deal. We have ‘Beat Army’ on our weights [in our gym]. When we’re preparing for Army, the focus increases tremendously. It reaches another level.”

Big Ralph Henry, the former Eastern Tech and Navy defensive lineman, knows this firsthand, and he knows that the Army players know it, too. When he looked to the opposing sideline he saw friends, not foes. On the field, he sensed a feeling of mutual respect, not animosity.

“We have so much in common,” he says. “We all work hard in school. No knock to any of the other colleges out there with football programs, but when it comes to academics the academies are second to none. We have to take all the engineering classes, take chemistry and physics and mathematics. Then you still, after a hard day of school, have to perform for your coaches.” At other universities, Henry adds, the football players probably hate practice, but not at the Naval Academy. “We thought that was the best part of the day, because school is so tough.”

He now lives in Beltsville, where he’s a management consultant for IBM and a lieutenant commander in the Navy Reserve. The former standout remembers his last Army-Navy game vividly, and when he talks about it, he sounds as if he’s ready to strap on a helmet.

“My senior year we got them good,” he says of Navy’s 34-6 victory in 2003. “I didn’t get any sacks that game, but I racked up like 5 to 10 tackles. It was just a dominant game. We brought everything together, and we smashed them. I almost felt bad for them, to be quite honest.”

He pauses for a few seconds, contemplating. “Almost.”