Lefty at Tochterman’s in Fells Point. —Photography by Mike Morgan

It’s early afternoon on a late September day. Lefty Kreh is standing in the shadow of an old oak tree, just a few miles from his Cockeysville home, with the light lying long and golden across the grass at his feet, and the air so crisp you can almost smell the pigments changing in the leaves. He’s pulling an orange line through the rings of a fly rod, readying me for today’s lesson. But “if you’re lookin’ for sympathy,” he says with a gap-toothed grin, “you’ve come to the wrong place.”

He gives a few tips in his Maryland drawl—pivot your body; get the end of the line movin’; don’t watch what you’re doin’; just straight away, straight back—and then, with a few surprisingly swift movements, jets his arm forward and gracefully drops the tip of the line exactly where he wanted it to go. “It’s that simple,” he says, as my palms begin to sweat.

Fly-fishing is simple, but then again, this is Lefty Kreh, the man who reinvented it. In his loose khakis and folded-up fishing cap, this is the man who took the staid sport of blue-bloods past and freed it up into an interpretive art form, fit for every man (and woman, too). With a shift of his hips, the fixed formality of a fly-cast transformed into a fluid extension of the angler—no longer a stiff mechanical motion but now an artist’s brush and his strokes of paint.

Five-foot-six with sky-blue eyes and a hearty laugh, this is the man who, from the streets of small-town Frederick, the depths of the Great Depression, and the trenches of World War II, would become the world’s best fly-fisherman. Throughout his lifetime, he has thrown line in every U.S. state, every Canadian province, and too many countries to count. He has caught over 100 species of fish and wet hooks with scores of celebrities, presidents, and CEOs who vie for his knowledge and time, from Ted Williams and Tom Brokaw to Jimmy Carter and George H.W. Bush. Ernest Hemingway and Fidel Castro in a single weekend.

Ninety-one years ago, out of our very own backyard, a legend was born. And yet, with the charm of a good ol’ boy and familial spirit of a long, lost grandparent, Lefty Kreh would never let you know it. To him—“a guy from Frederick, Maryland, with no more than a high school education,” as he so often puts it—it has just been a lucky life. And yes, in its own way, simple, too.

Before Baltimore had skyscrapers, or the Chesapeake Bay had bridges, or highways spread like tributaries across this state, Lefty was born Bernard Victor Kreh in what was then the small town of Frederick in 1925. At that time, Charlie Chaplin was the biggest star in Hollywood and Jack Dempsey was heavyweight champion of the world. Calvin Coolidge was president, and the Roaring Twenties were in full swing, with The Great Gatsby about to hit shelves. Not that those gilded days were apparent in Lefty's pocket of the world. At six years old, his father died after being kicked in the chest during a basketball game, leaving behind a young wife and four small kids at the height of the Great Depression.

“In the 1930s, nobody had any money, and here was my mother, all alone with four children,” says Lefty. “But she was very prideful, tougher than an automobile tire, so she wasn’t going to give us up.” Instead, as part of FDR’s New Deal Program, the family went on “relief” and was allotted a small house on North Bentz Street in a poor Black neighborhod. It was there that Lefty became “Lefty,” as local kids knighted him the nickname—a scrappy little southpaw with a knack for sports.

Hardships aside, Frederick was a young boy’s paradise at the time. Just a quarter-mile outside of town, the fields were filled with game, the streams were brimming with fish, and the Monocacy River became his playground. “In those days, the rivers were teemin’ with life,” he recalls. “There were fish, and freshwater mussels, and crawfish, and all kinds of bait. You can still find old shells along the bottom today.”

By the time he was 12, Lefty had two options: school or work. “We didn’t have no money, but my mother said if I could make enough to get myself clothes and lunch, I could go to high school.” Education was a privilege, so Lefty got busy.

“When a mussel moves along the river, it leaves a little track in the mud,” he says. “Some friends and I would spend all day pickin’ ’em up, puttin’ ’em in a little backwater, and huskin’ ’em out like oysters.” In the evening, he’d build a fire, cook hot dogs, and hang strands of twine to tree limbs that dangled over the riverbank. At the end of the line was a hook, and on the end of that hook was one of those mussels. “The catfish would swim the banks at night and the limbs would act like fishin’ rods.” So twice a night with kerosene lanterns, he’d pole along the water and pick off his daily catch.

You might say he worked his way through Frederick High as a commercial fisherman, selling his nighttime bounty the next morning to Miller’s Cash Market for 10 cents a pound, which was a lot of money in those days. In the wintertime, he also sold muskrat and mink pelts to local hide dealers, and, as the man of the house, hunted and trapped to put food on the dinner table. “But it was a totally different world back then. Nobody thought twice about 12-year-old kids runnin’ around outside and stayin’ in the woods all night.”

By the early 1940s, though, the world wasn’t all full

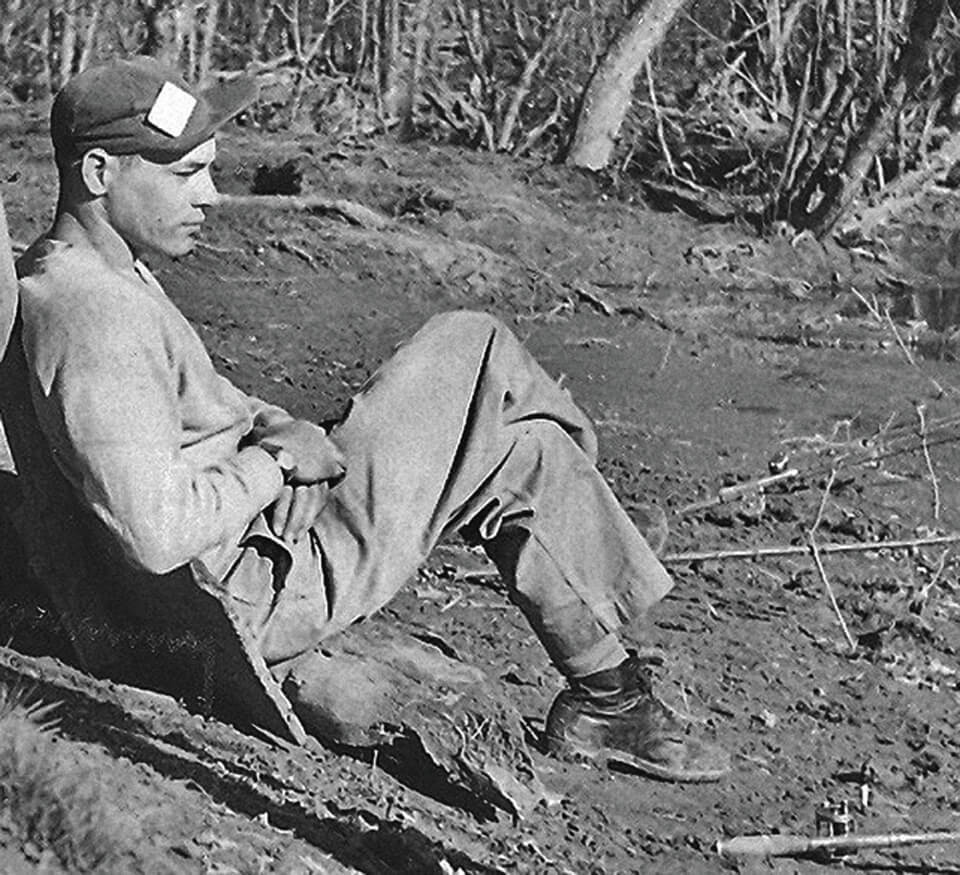

waters and fat-bellied fish. By the time Lefty graduated, World War II was in full swing and America had just joined the fight. The week after he

threw his cap in the air, Lefty enlisted, serving in the 69th Infantry Division that would eventually meet with the Russian army at the Elbe River.

Before the war’s end, he helped liberate a concentration camp, suffered frostbitten feet at the Battle of the Bulge, and racked up five battle stars, all of which he shares with a modest matter-of-factness. “We

were scared as hell a lot of the time, but today we all agree: It was the best experience of our lives. You learn that you can do things you never thought

you could.”

Lefty as a young soldier in Europe during World War II.

In August 1945, the 20-year-old serviceman was sent home for a 30-day furlough, expecting to then head out to the Pacific. “I was walkin’ down the streets of Frederick, when all of a sudden, sirens started goin’ off. Women came runnin’ outside, blowin’ kisses and dancin’ around. Cars were honkin’ their horns.” We had dropped the atom bomb.

With the war soon over, Lefty got a job at Fort Detrick, the country’s biological warfare center, located just north of town. As a plant operator, he spent 18 years growing anthrax for Army scientists. One day, he got a tear in the right arm of his protective suit. “The whole thing turned black and I was in the hospital for a month,” he says. But they got the deadly bacteria isolated, and now, if the Army ever needs it, for research or some top-secret request, “they look up BVK-1.” That’s right, Bernard Victor Kreh. “You can find that on the Internet.”

As a shift worker, Lefty often worked nights, which, like a gift to his inner child, freed him up to hunt and fish all day. In no time, he started to gain a local reputation for being “the hotdog bass fisherman of Central Maryland,” he says, before an inevitable quip. “The fish didn’t always seem to think so.” But to better his craft, Lefty had been rigging bait here, and tweaking lures there, and soon enough, he caught the attention of a local newsman named Joe Brooks.

In 1947, the two men went fishing on the Potomac River, just below Harpers Ferry at the crossroads of Maryland and West Virginia, and within a matter of minutes, Lefty’s world changed forever. Eyeing some rings rippling on a nearby pool, Brooks walked out onto the edge of a rock, pulled out something Lefty had never seen before—a fly rod—and with the flick of his forearm, dropped a little black-and-white fly out on the water and instantly caught a fish. Then another. And another. “That happened about 10 times and I said, man . . . I got to get me some of that!”

The next day, Lefty hopped in his Model A Ford and drove down old Route 40 to a small fishing shop called Tochterman’s in Baltimore City. There, on Eastern Avenue, he bought a Pflueger Medalist reel and South Bend fiberglass rod, then followed Brooks to Herring Run Park for his first fly-casting lesson.

But Lefty and the fly rod were not fast friends. Perfecting his cast was a slow, arduous process. Still, he practiced and practiced and gradually developed his own way of doing things.

To him, the tried-and-true casting method was inefficient. For centuries, fly-fishermen had been moving

nothing but their forearm, ticking between the figurative 10 and 2 o'clock, 10 and 2 o'clock, like a metronome pendulum. “It just didn’t make sense to me,” he says. “Fly-fishermen were immobile,

just usin’ their wrist and arm. They’d been doin’ what the English taught them hundreds of years before and hadn’t changed a thing. But you use the rest of

your body, even when playing Ping-Pong.” So he decided to put his hips into it.

Lefty catches rockfish on the Severn River with his first fly reel and rod in 1955.

Around this time, Lefty also caught another catch. One night, he went to see a movie at Frederick’s old Tivoli Theatre and met a beautiful blonde behind the ticket-booth counter. That night, he walked her home. Six months later, they were engaged. A year after that, they were married.

“Ev was about this big”—gesturing toward five feet high—“and you didn’t piss her off,” says of his late wife with a wink. “But we got along crazy, we really did,” calling her “the greatest woman” there ever was and their marriage “the best there’s ever been.” The couple rented a house on West Patrick Street and eventually had two children—Victoria, nine months to their wedding day, and Larry, three years later, who fished with Lefty every weekend.

In the decade that followed his first fly lesson, Lefty honed his new fishing technique, and, in 1965, penned an article for Outdoor Life called “New Way to Fly Cast.” For an old guard as traditional as fly-fishermen, the idea was not warmly received. “People got all upset, wrote hundreds of letters, and said this is heresy,” Lefty says. “But tradition is only good as long as it don’t stand in the way of improvement.”

At that point, he’d already been a writer for some time. His career began in 1951 at the Frederick News-Post. He was still working eight-hour days at Fort Detrick and didn’t know much about newspapers, but he knew what to write about. With firsthand experience and a no-nonsense style, his how-to “Maryland Afield” columns took off, and the next thing he knew, he was writing for the Towson County Paper, Montgomery County Sentinel, and Virginia’s Winchester Star. “At the time, my wife and I didn’t have enough money to buy a mosquito underwear,” Lefty cracks, “so I was lookin’ for other sources of income.” Along the way, he also took a liking to photography, eventually working with big names like Leica and Nikon, even becoming a photo consultant for L.L. Bean.

Still, with the energy and appetite of a young man in his early 30s, Lefty got to thinking: What if he could give his readers advice outside of the Old Line State? What if he could travel the country, give quick clinics at local outdoor clubs, and then find the “best damn fisherman in town” to teach him their waters and ways? He started putting out feelers, abd before long, invitations were rolling in from around the world. Which is why now he can tell you where to find the best trout streams in England or what to use for barramundi in Australia or how to snag Atlantic salmon on the Alta River near the Norwegian Sea.

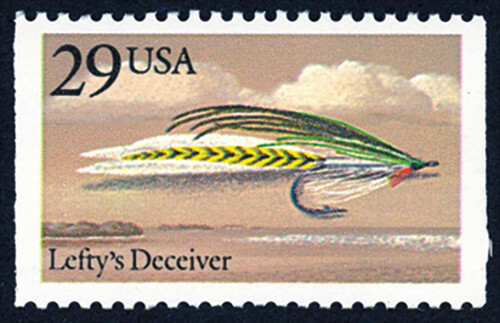

And his wide eyes didn’t stop there. Even when learning to tie flies, Lefty would buy a bunch, cut them apart, and see how they were put together. Out of that came the Lefty’s Deceiver in the late 1950s, now the ambrosia of the aqua kingdom and one of the most popular flies in the world. Lefty has caught dozens of species on that single pattern, from stripers to sailfish, and in 1991, the federal government decided to give it its own stamp (though Lefty’s still sore over the fact that he had to buy his own).

“I’ve had customers from Russia, Asia, Saudi Arabia, all the way through South America, and everybody knows the Lefty’s Deceiver,” says Tony Tochterman, owner of Tochterman’s tackle shop in Fells Point and son of Tommy Tochterman, who sold Lefty his first fly outfit there. Since then, Lefty has also designed his own rods and developed fishing lessons to live by, printed in some 31 books. He’s currently working on number 32, he says.

For a while there, he even lived in Miami, running the world’s largest fishing tournament, but all the while, writing kept calling him back. In 1972, after a brief stint at the St. Petersburg Times, Lefty was approached by the Baltimore Sun, and for the next 18 years, he wrote three columns a week, teaching area outdoorsmen everything from the best places to fish and what tackle to use to the weather’s influence and why to stop for wildflowers. On the side, he also wrote books, taught clinics, sat on the staff of national magazines, and traveled the world. “I really had so many irons in the fire,” he says. “I was busier than a Baltimore homicide detective.”

Lefty shows the difference between the traditional fly-casting method and his signature technique. —Footage by Meredith Herzing

And truly, he was. Over the course of his lifetime, from those club invitations to his own excursions, Lefty has fished everywhere from the Chesapeake Bay and Rocky Mountains to Iceland and the Amazon. He tells stories about Christmas Island, the world’s largest atoll, 100 miles around, just brimming with bonefish. About trips to New Guinea, where he gave M&Ms to natives and bought watermelons out of dugout canoes. About campfires with anthropologists in the outback of Australia—“at night, the stars are unbelievable”—and about catching the biggest damn snook he ever hooked in Belize.

Lefty’s tales transport you like Treasure Island or Huckleberry Finn, full of characters and adventure, mishaps and good fortune, hearty punch lines and good-intentioned hyperbole. They’re part campfire yarn, part Big Fish, and as he tells them, you can see the pure delight in the pull of his cheeks and creases of his eyes. Like, this really happened! Like, can you believe it? Like he still can’t himself.

He’ll tell you about his friendship with baseball legend Ted Williams, who would “piss and moan” whenever Lefty wouldn’t eat his fancy French food. (“I don’t eat nothin’ but four colors, and they gotta be well done.”) He’ll talk about the day after a Missouri rainstorm when he helped golf pro Jack Nicklaus fine-tune his cast. (“He was grinnin’ like a Halloween pumpkin.”) He’ll show you pictures of him and country music star Jimmy Dean.

But to Lefty, there’s no difference between celebrity and common folk. Not in the fishing world, anyway. He still gets a kick out of big-name people picking him up in limos and private jets, but as he sees it, “fly-fishing is a leveler.” And either way, it isn’t win-or-lose. “It’s like a game of chess,” he says. “You go to the water, you figure out what the fish are doin’, then what flies to use, then the approach, and the presentation. But even if you don’t catch anything, you had fun playing the game.”

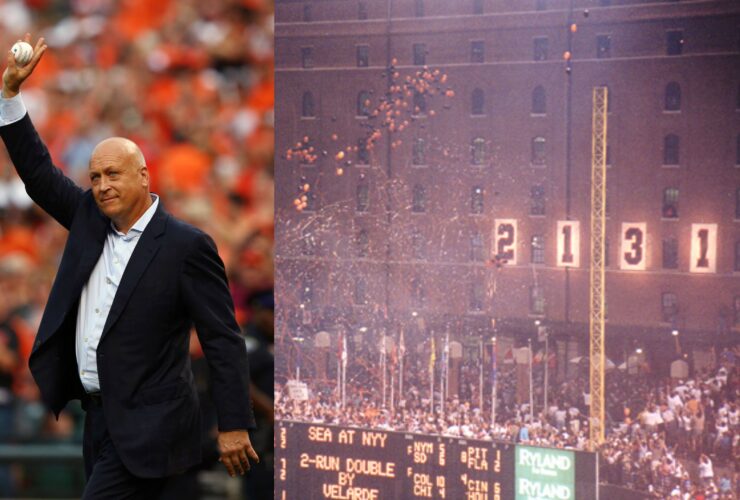

Some of his closest friends are A-list celebrities, like Tom Brokaw, who met Lefty on a bone-fishing trip 10 years ago. “It was like a Little League shortstop meeting Cal Ripken for the first time,” says the renowned news anchor. “Lefty was a legend and he lived up to his reputation.” The two eventually started a fly-fishing TV series, now called Buccaneers & Bones on the Outdoor Channel, which features the likes of Patagonia founder Yvon Chouinard, movie star Michael Keaton, and comedian Jim Belushi. (“He’s a wild man,” says Lefty of the latter. “His ink don’t dry. Calves like turkey legs.”)

Spending full days fishing in 17-foot boats and sunshine over the course of six seasons, the group has become good friends. In fact, Lefty is now honorary godfather to Brokaw’s grandson. “Lefty has taught me that, whatever you care about, do it well, with originality, and stay humble,” says Brokaw. “He is a very special friend, in a boat and on dry land.”

“And he’s got a way with women!” exclaims Chouinard. “They’re absolutely attracted to him like you wouldn’t believe—and you know it’s not his good looks. I think women have a way of telling who’s real and who’s not, and they see that in Lefty.”

Lefty loves women, too. Not in any romantic sense—he had the best woman in the world, remember. But he respects them, thinks they’re “smart as hell,” and feels cool as a clam in a room full of ’em. Fly-fishing has been a long-established boys’ club, but Lefty’s excited to see the sport become more and more inclusive.

“He’s a real champion of women, doesn’t have a mean bone in his body, and is generous to a fault,” says Candy Thomson, public information officer at the Maryland Department of Natural Resources, who Lefty staunchly supported when she became outdoors editor, aka his old post, at The Sun in 2000.

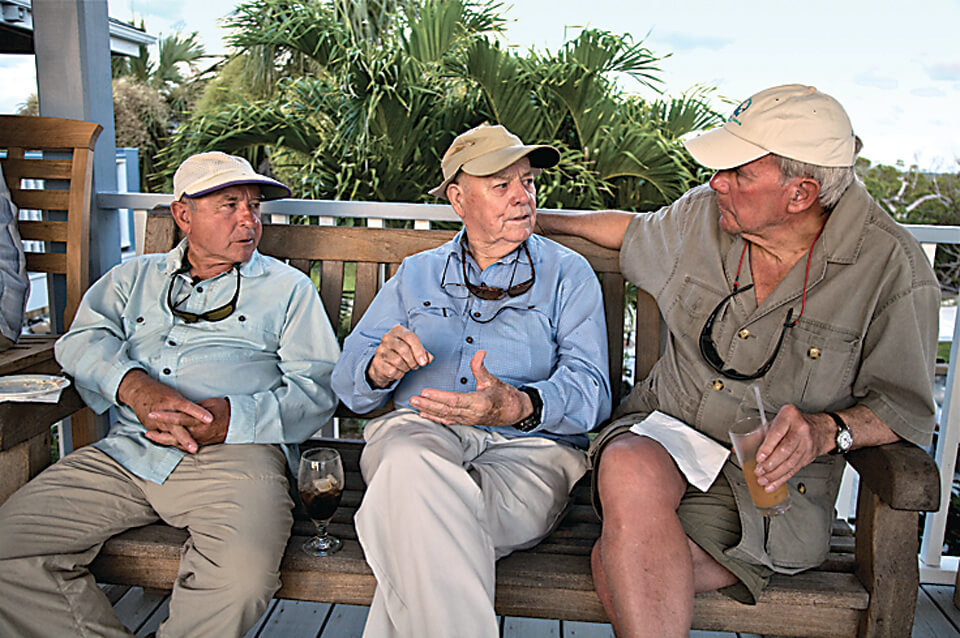

Patagonia founder Yvon Chouinard, Lefty, and former NBC Nightly News anchor Tom Brokaw in the Bahamas.

Lefty greeting people in New Guinea.

Lefty on the banks of the Monocacy River in the early 1950s.

Lefty and his wife, ev, in their cockeysville home in mid-2000s.

The Lefty’s deceiver stamp, created in 1991.

But even as fly-fishing gains new followers, Lefty is not blind to the biggest concern surrounding the sport today. Over his nine decades, he has watched our waters and landscapes dramatically change, from lush, life-filled lakes to polluted, perishing riverbeds. “In 50 years, we lost so much,” he says. “We used to put canoes in the Monocacy at the Pennsylvania line and float different stretches all the way down to the Potomac. Now there are streams we used to wade in that are no longer there. They’ve dried up.”

He misses the fireflies, too: “You used to drive around in the summertime evenings and there were billions of them. Just billions.” And he misses the croak of the American toad: “Raaaak, raaaak, raaaak. I haven’t heard one in 20 years.”

It’s not just thirsty waterbeds and missing fauna—overfishing is another problem in need of address. “In my opinion, there shouldn’t be any commercial fishing in the Chesapeake Bay anymore,” Lefty says. After years of limitless catches and decreased water quality, “we now realize we have a resource that we’ve badly managed. What happened to rockfish is the same thing that’s happened to crabs and oysters. Nothing is infinite.”

But he’s not ready to give up: His casting legacy and conservation efforts have garnered him awards, accolades, and inductions into halls of fame. In 2012, Maryland paid homage with the “Lefty Kreh Fishing Trail” along the Gunpowder River in Baltimore County.

“Let me put it this way,” says Jim Gracie, co-founder of the Maryland chapter of Trout Unlimited and former chairman of the state’s Sport Fisheries Advisory Commission, who has worked with Lefty on conservation for over 40 years. “I’ve been involved in dozens of restoration efforts and virtually every water-quality regulation in the state of Maryland since 1973. And I wouldn’t have done any of it without Lefty’s help.”

Still, Lefty isn’t one for praise. And as far as being called a legend? “Look, I don’t have no patches, I don’t keep no records, I ain’t never gotten

fluffed up about that stuff,” he says. “I tell people: you can know a hell of a lot, but you don’t know how to exhume an Egyptian tomb. You don’t know how

to identify bacteria. My mechanic is smarter than me because he can start my car when I can’t. Even if you know a whole lot about somethin’, you don’t

know shit about hardly anything.”

Lefty casts on Conewago Creek in Pennsylvania.

For Lefty, it is less than 10 percent about catching the fish anyway, and at least 90 percent about the environment he’s in and company he keeps. He’s caught thousands of fish and says he’d be fine if he never caught another. Now his greatest enjoyment comes from helping others find that thrill. “And when you catch your first bonefish?” he says. “It’s like me catchin’ mine all over again.”

It’s that mentality that’s made Lefty a second dad to dozens throughout his lifetime. He’s taught strangers how to fish and then ended up in their weddings. He’s been asked for romance advice from countless students. And he brings grown men like Tochterman to tears. “I was 5 or 6 when I first met Lefty—he wasn’t anybody special to me at that age, he was just another good customer and friend of my father’s,” he says. “But Lefty means more to me and my industry than any man ever has or will. He has taken the average individual who doesn’t know a goddamn thing but his love for fishing, and he’s put him on the same playing field as the highest celebrity ... ”

“I should’ve been a damn priest,” Lefty quips. “But I just like people, and if you like people, people like you.”

After a few recent health scares, Lefty has decided to travel less—every few days instead of every other. “I’m one of them independent types,” he says with a pout. “But I can’t complain. I never thought I’d be sleepin’ in my own bed at this age.”

But at 91 years old, pacemaker and shoddy knees be damned, Lefty’s not slowing down anytime soon. Today he’s finishing up this fishing lesson with me, and tomorrow he’s off to Dallas or the Bahamas. South Carolina or Massachusetts or Montana after that. The calendar that hangs in his home office amidst old photographs and fly boxes only has a few free days this month. His inbox has 103 unread emails.

“Lefty’s gonna outlive me,” says the DNR’s Thomson. “He just has this childlike enthusiasm. He is amazed by all of his good luck. But he makes so much of it. I think if you rub his balding head, good things might happen.”

And today, out here, this afternoon, beneath the oak trees and afternoon light, Lefty is the same young man you’d find fishing the banks of the Monocacy three-quarters of a century ago on a full-moon summer’s night. The rod rests in his hand as if he were born with it, and the line unrolls with a weightless grace, like he’d summoned it to do so. He still makes mistakes, but he knows that, with each motion, you’re only as good as your desire to be better.

So he’ll be out there ’til the cows come home, because, retire? For the boy who started working at age 6. Quit? For the man who made it through depression and war, who changed the face of fly-fishing as we know it, and who, like a “bumble bee in a ball jar,” needs to always be doing something.

“Hell no,” he says, a twinkle in his eye. “I’d be bored to death.”

Lefty talks technique and shares stories from his legendary life. —Video by Justine Hulsey and Meredith Herzing.