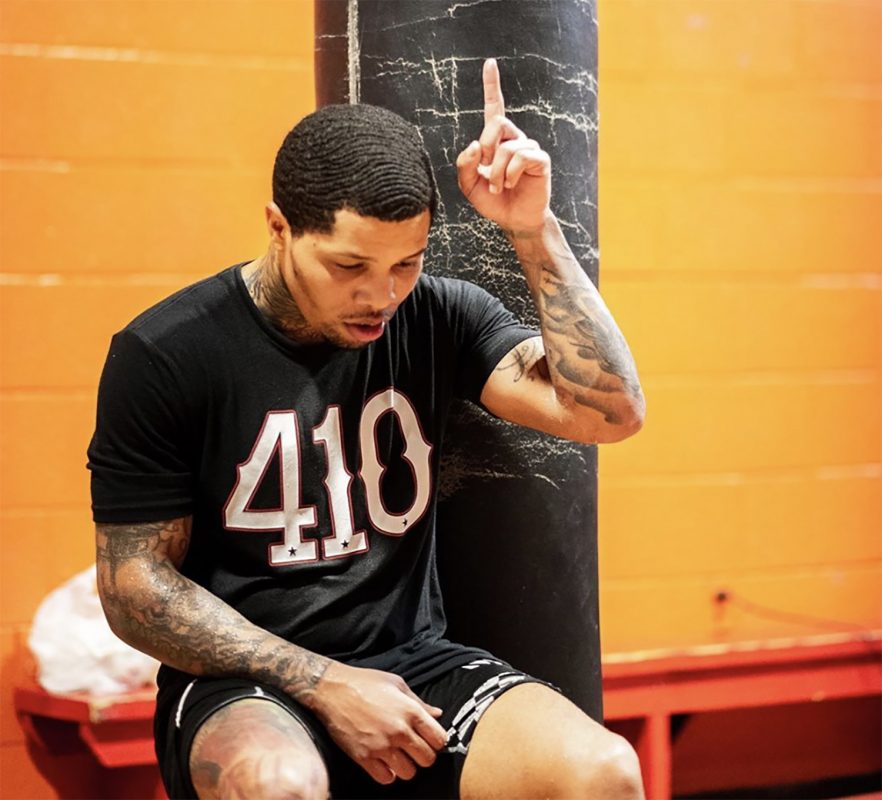

In the same small, former basketball gym on Pennsylvania Avenue that a pair of uncles first dragged him to at age 8 after seeing him fighting on a Sandtown street—and where he’s since thrown millions of more punches with gloves on, sweated off pounds of weight, and honed his boxing skills, mostly with only his coaches and other fighters watching—Gervonta Davis bounced around the ring last week at Upton Boxing Center, the spotlight fully on him.

A giant promotional banner hung from the ceiling, bearing the pertinent information for all to see—Gervonta Davis vs. Ricardo Nunez, alongside their giant likenesses, Saturday, July 27, Royal Farms Arena, Live on Showtime. The eyes and smartphones of a couple hundred fans and the media in attendance, fanning themselves to keep cool in a crowded room warmer than the West Baltimore air outside, tracked Davis’ steps and shadow jabs during a public workout.

“This right here,” said Calvin Ford, the real life inspiration behind the character, Cutty, from The Wire. He’s a former drug dealer turned neighborhood do-gooder who runs the gym and has coached and mentored Davis since he showed up at the front door 16 years ago, “This is what we dreamed about.”

It’s a story worthy of a book—or another HBO show. As we wrote in this December 2016 story, as a tiny kid, Davis often slept on the floor of his drug-addicted parents’ house in possibly the roughest neighborhood in Baltimore City before going into foster care. He “came from nothing,” says Mayweather Promotions CEO Leonard Ellerbe. And, excuse the hyperbole, “he’s made himself into something.”

Now 24, and with a one-year-old daughter of his own, the 5-foot-6, 130-pound spark plug is about to host the homecoming championship fight of his childhood and young adult dreams, before an expected sold-out, 12,000 person crowd Saturday night at downtown Royal Farms Arena. It’s a show, he says, that’s he’s long waited to star in. Over the last six years as a pro—in a career that’s taken him to London, Los Angeles, and New York—Davis has compiled a 21-0 record with 20 knockouts. In January 2017, when he won the IBF junior lightweight title, he became Baltimore’s first world champion since Hasim Rahman in 2001.

Davis’ super featherweight bout against Nunez, a 25-year-old challenger from Panama with a 21-2 career record, marks the first championship boxing match in the city in more than 80 years. The last time being when Harry Jeffra won in 1940 at Carlin’s Park. It comes in a venue that, in a previous life, hosted six Sugar Ray Robinson fights.

It’s also Showtime’s first-ever boxing broadcast from Baltimore, and the undercard is filled with other local fighters who Davis hand-picked to show off—including super lightweight Malik Hawkins (15-0) and 19-year-old super featherweight Malik Warren making his pro debut. They’ve all known each other for years, and have trained together again the last two months—sparring at Upton and taking three-mile runs along North Avenue.

“My brothers,” Davis said. “I’m not fighting alone. We’re all fighting together.”

Think what you want about the violent, gladiator-like nature of the sport we’re talking about (and, yes, a pro boxer just this week sadly died from injuries sustained in the ring), but boxing has been Davis’ refuge, and it provided the platform for a tale of triumph in a city that is on pace for 300-plus homicides for the fifth consecutive year. “We used to be young,” Ford says, “sitting down talking about these times. Now we’re actually in the mix of it.”

And, Saturday, if even only for one night, Davis said he wants to be a “crime stopper,” like Patterson High basketball player Aquille Carr was once known. “It was like they shut down the whole city to watch him,” Davis said. He’s on his way. Mayor Jack Young just presented “Tank” a golden key to the city this week, and Ellerbe said this event won’t be Davis’ last here.

So, what should we expect? As he’s shown in the past, Davis is capable of quick knockouts with his ferocious left fist, but it sounds like he wants to give the crowd its money’s worth. “I always want to give the fans a great performance,” he said on a conference call promoting the event. “That’s my job when I step in the ring, not just try to go in there and look for a knockout, but try to give [the fans] excitement. Give them what they paid their money for.”

He’s a headliner, sure, who “very soon will be the biggest star in the sport,” Ellerbe said. “That’s where we’re guiding him.” But to simply talk about these good times foolishly overlooks the climb it took to get here. Davis’ young eyes have seen tragedy.

“All of them got killed,” he says of the fighters—Angelo Ward, Ronald “Rock” Gibbs, Ford’s son, Qaadir—he once looked up to for inspiration. And danger lurks. Four private security guards watched over last week’s public workout, and a personal guard was never more than a few feet away from Davis. As he finished up a few interviews toward the night’s end, his guard closed a fist, signaling it was time to leave.

Although he says he wants to be a role model, Davis is still admittedly maturing himself. Just in February, he was arrested for an alleged fight at a Northern Virginia mall, news that made TMZ.

“I’m getting older and wiser,” he said. And there’s an endless stream of social media posts, at times showing off the things he’s spent his money on, and the combative barbs he trades with potential future opponents that might give off the wrong impression. “But deep down Tank has a tremendous heart,” Ellerbe said in the middle of the Upton ring, shortly before Davis presented 100 free tickets to Saturday’s fight to local foster children. If all goes according to plan, this is just the start of his star turn, or at least the next few chapters of the story.

“It’s amazing coming home,” Davis said. “I always believed if I was in arm’s reach of a kid, it would mean more than doing it from away. I want to show them anything is possible. I came from the same projects, the same block.”