Sports

Baltimoreans Didn’t Want a New Baseball Park 30 Years Ago—Then We Saw Camden Yards

Funding for renovating Memorial Stadium? Absolutely. Abandoning Memorial Stadium? No way.

Larry Lucchino grew up in the Greenfield section of Pittsburgh, the next neighborhood over from Schenley Park and Forbes Field. When the former Orioles president was a kid, he and his buddies only had to jump on a city bus to see Bill Mazeroski, Smoky Burgess, Dick Groat, and a glorious young outfielder named Roberto Clemente in the turn-of-the-century ballpark.

Built in 1909 with Pittsburgh’s finest steel, the elegant, Bouquet Street-situated Forbes Field possessed a wonderful repeating arch and window exterior, copper roof, asymmetrical dimensions, and a scoreboard embedded into the left field wall.

“It was a baseball field in a neighborhood park,” says Lucchino, who was 15 when Mazeroski smashed a walk-off home run over Forbes’ fence in the seventh game of the 1960 World Series. “Maybe the obsession with old ballparks began there. I also grew up going to football games at Pitt Stadium, which was a concrete doughnut,” he continues. “Two different concepts.”

In short, this is why Baltimore has Camden Yards.

Thirty years after the fact, we’ve forgotten that most Baltimoreans—yes, even Orioles fans—would’ve rejected building Camden Yards had it gone to ballot. Funding for renovating Memorial Stadium? Absolutely. Abandoning Memorial Stadium? No way. But all the debates and objections about public money going for a new stadium—recall the Marylanders for Sports Sanity lawsuit?—and about World Series memories and Waverly being left behind, were erased the moment Rick Sutcliffe’s called third strike clinched the O’s Opening Day shutout on April 6, 1992. (Irony: city planner Evans Paull, who lived near Memorial Stadium, had organized the local fan group “Save Our Stadium,” before going to work on, and falling in love with, Camden Yards.)

Of course, the full story behind The Ballpark That Changed Baseball Forever™—the Orioles trademarked the phrase in 2012—is more complicated than a reluctant fan base and the team president’s nostalgia. It involves a city jilted by a duplicitous Colts owner and his snowy night run out of town; an O’s team then-owned by a big-shot Washington lawyer; a stubborn Baltimore mayor on his way to the governor’s mansion; a Syracuse University student’s architectural thesis; and a 31-year-old woman with no baseball experience hired to oversee the entire Camden Yards project.

“It plays. That was my immediate thought after the last out on Opening Day,” says Janet Marie Smith, the sharp urban planner ultimately hired by Lucchino to manage the development of Camden Yards for the Orioles. “You test everything you can. We’d built a scale model to test the impact of the warehouse on the wind. You flush all the toilets at once. You run a vendor check. But you just don’t know until there is a ballgame, and so you hold your breath. Then, the game barely lasted two hours. It ended in the middle of rush hour [because of Opening Day’s late afternoon start], but no traffic jam materialized.”

The combination of parking, trains, and pedestrian access worked. “But no, I didn’t think of it as ‘a hit.’ We had the whole season in front of us.”

The Orioles shortstop that day, who would celebrate his own historic moment at the former train yard three years later, knew otherwise. “It feels like baseball has been played here before,” Cal Ripken Jr. said at the time.

Affectionately known as “The Old Grey Lady of 33rd Street,” Memorial Stadium reached the end of its natural lifespan at the worst of times. Baltimore was a ship taking on water in the economic tumult of the late 1970s and early 1980s. The steepest population decline in city history came in the decade leading to 1980, when 120,000 Baltimoreans, including our NBA team, left for subsidized suburban pastures. Mayor William Donald Schaefer famously responded by charting a bold course and remaking the Inner Harbor, but even as that effort succeeded beyond all hopes, the departures continued. Among others renting moving trucks, our beloved Colts rolled out, heading for a new, domed stadium in Indianapolis. That left the teetering Orioles, who had been sold in 1979 to high-profile Washington defense attorney Edward Bennett Williams. He soon began signing one-year leases at Memorial Stadium, while making his own demands for a new park.

Over the previous decade and a half, Astroturf concrete multipurpose stadiums had been built in St. Louis, Houston, Cincinnati, Philadelphia, Arlington, Seattle, Minneapolis—and, yes, Pittsburgh—many replacing historic urban parks. The Washington Senators had been lured to Texas after 1971, and Williams and others in the Orioles front office saw the opportunity to create a regional franchise. The concern in Baltimore was our championship Birds might migrate further south, and, in fact, six months after Williams bought the team, Schaefer said publicly he believed they were on their way to Howard County.

Against expectations, however, Williams assured Schaefer he’d leave his options open about keeping the Orioles in the city. Unlike the owner of the Colts, Williams kept his word to Schaefer, too, giving him time to act, as mayor and then later as governor. Shortly after the Colts left, Schaefer set up a local commission to study the twofold stadium issue—the goals at that point were to lure an NFL team back to Baltimore and renovate Memorial Stadium to keep the Orioles in their nest.

Meanwhile, the Maryland Stadium Authority was formed in 1986 and a new state commission that year recommended a 70,000-seat multi-purpose stadium in Lansdowne in Baltimore County. Their findings touted the beltway-adjacent site because it was equidistant from Baltimore City to Washington. City of Baltimore planners, including Paull, responded with their own study, however, which poked holes in the state’s findings, specifically calling out the wisdom of constructing a massive parking lot that would encircle the stadium, and proposed a bold idea: a brand new stadium in downtown Baltimore, namely Camden Yards. They cited the benefits: public transportation, which would include a new light rail, and nearby hotels, restaurants, bars, and tourist attractions already in place.

“We leaked it to the press,” Paull says proudly today. “It worked. Momentum turned back to a downtown park.”

The Camden Yards location—Port Covington had also been under consideration—had the O’s backing. It satisfied Lucchino’s desire for an urban park and Williams’ wish to move closer (than Memorial Stadium at least) to baseball fans in the D.C. area. Lucchino, all along, had remained adamant about building a baseball-only venue. He’d recognized the friendly confines of Wrigley Field and Fenway Park were the reason Chicagoans and Bostonians turned out even as the Cubs and Red Sox often put mediocre clubs on the field. Williams and Schaefer eventually came around to the idea, too. In 1987, just months after becoming governor, Schaefer pushed the General Assembly to approve the Camden Yards project and then blocked a referendum campaign to put the whole thing on the ’88 ballot—which polls had indicated would not have passed.

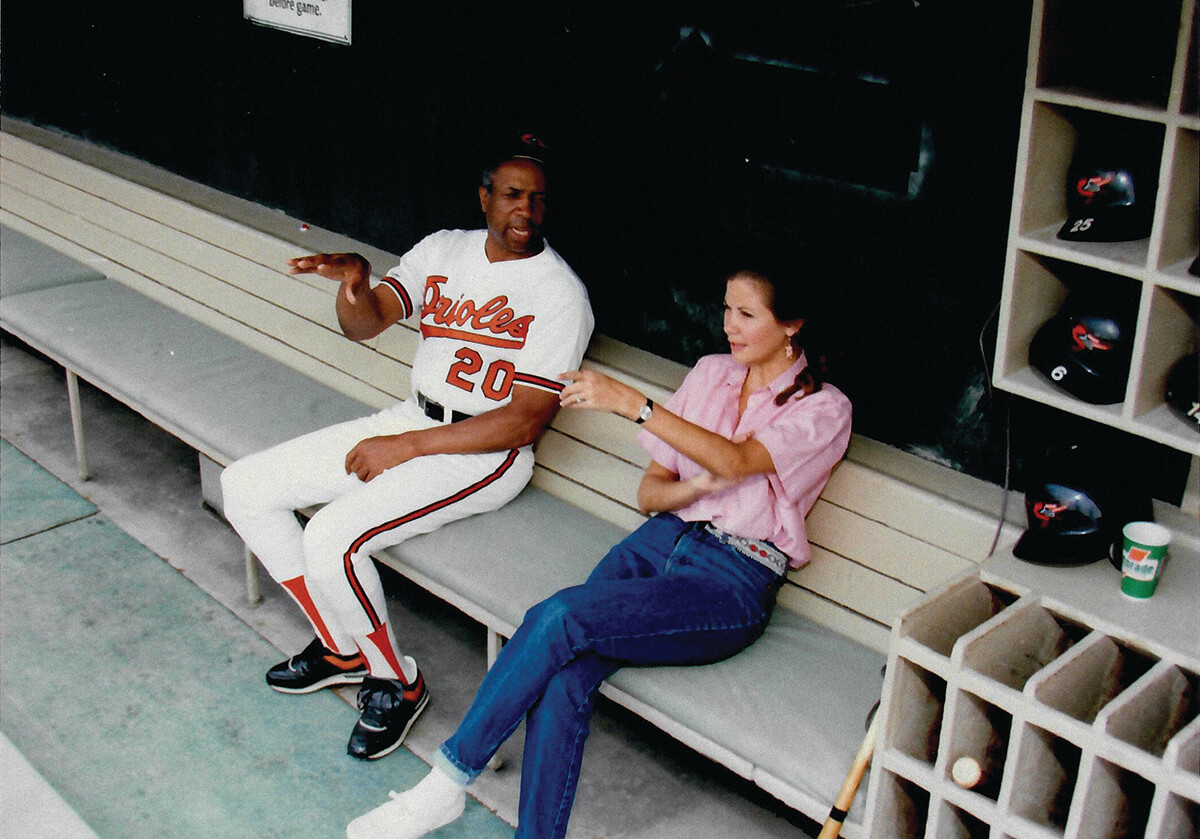

Lucchino, who had been hired by Williams to serve as the team’s vice president and general counsel, was promoted to team president in 1988. That off-season, he got a resumé from Janet Marie Smith, which she’d sent on her 31st birthday. She was from Mississippi, but she had studied the Inner Harbor in graduate school. She’d worked on a Battery Park makeover in Manhattan and a similar effort in Los Angeles, though never in baseball. Lucchino found her resumé in his HR director’s “thanks, but no thanks” file.

“This is a woman who is an architect with a master’s degree in urban planning,” Lucchino recalls saying to his HR head, explaining he had enough baseball men around him. “Don’t you think a person with this kind of experience is someone we ought to be talking to?”

Lucchino invited Smith in for an interview and promptly asked if she knew what league had the designated hitter. She rightly took offense and he responded by asking her to look at an early draft of the Camden Yards master plan in his office. She identified some shortcomings in the working design and impressed Lucchino with her mix of baseball knowledge, aesthetic eye, attention to detail, and confidence.

“The plan hadn’t yet come together,” Smith says, recalling the preliminary drawings didn’t fully capture Lucchino’s vision of an old-style ballpark, which took cues from its urban landscape. If he wanted someone who would offer the conventional sports response it wouldn’t have been the right fit, she says.

Little did Smith know her career was about to change forever. Not only did Lucchino hire her for the job, she would go on to oversee ballpark efforts in Atlanta, Boston, and L.A., where she now works for the Dodgers. Twenty years later, in 2009, she returned to supervise Camden Yards’ renovation.

With Smith in place to help carry out Lucchino’s vision, baseball was about to get its first retro ballpark—Lucchino fined staff members $5 whenever one of them used the word “stadium”—of the post-World War II multi-purpose era. But not until Smith and her team figured out what do with the eight-story, 1,116-foot warehouse, the longest brick building east of the Mississippi. The 1899-built B&O warehouse that many people thought was standing in the way of progress, and blocking a potential view of the harbor, instead became the key to its entire concept.

The man who saved the warehouse is largely forgotten today. But it was fifth-year Syracuse architectural student Eric Moss who made the first model of Camden Yards utilizing the neglected B&O building. A Phillies fan who grew up going to Veterans Stadium, Moss had an epiphany during a visit to Fenway. While casting around for a final project idea, he’d become aware of the Orioles’ relocation plans, and the image of the warehouse reminded him of Fenway’s Green Monster. He thought, what if they incorporated the warehouse into the right field fence? Among Moss’ thesis jurors was Syracuse alum Adam Gross of the Baltimore architecture firm Ayers Saint Gross, who hired the young man and brought him and his plans back in the hopes of winning the Camden Yards contract. The Ayers Saint Gross bid didn’t win, but Moss’ idea generated news and buzz.

That said, the back and forth over the warehouse continued for several years. Among the warehouse detractors, notably, was John Steadman, the longtime Evening Sun columnist. “That warehouse offers absolutely nothing, and it destroys the vista of downtown Baltimore,” Steadman wrote. “And if you buy the best seat in the house, next to the Baltimore dugout, you’re going to spend nine innings staring out at a brick wall that reminds me of the Maryland state penitentiary.”

Steadman was wrong, obviously. The warehouse brought in almost everything we value about Camden Yards, and probably now take for granted. For starters, the warehouse, like the train tracks out front, runs north and south. By coincidence, the ideal direction for a third-base line is north and south because it means the sun, crossing east to west, never shines directly in the eyes of batters or outfielders. That also meant that the warehouse could sit perpendicular to the first-base line, and its massive backdrop, as Moss imagined, would create a sense of authentic intimacy.

And it meant Eutaw Street, with the Bromo-Seltzer Tower in view to the north, could be gated at each end on game day, and left open on non-game days to further establish a genuine connection to its immediate environs.

“I’m not gonna say I had all the best ideas,” Moss told Bloomberg CityLab several years ago, “but I still think it would be fun to have the warehouse in play.”

“…BUT I STILL THINK IT WOULD BE FUN TO HAVE THE WAREHOUSE IN PLAY.”

In the end, the debate around keeping the warehouse came down to the cost of its renovation and whether or not it could be utilized, because the Maryland Stadium Authority didn’t intend to assume care of an empty building. Developer Bill Struever, who was doing groundbreaking adaptive re-use projects around the Inner Harbor, was brought in to provide his expertise and offered encouragement that the warehouse could be put to good use. Once there was a realization the building could house the Orioles’ and Maryland Stadium Authority’s offices, the park’s commissary kitchen, the Stadium Club, and the locker rooms for stadium workers, form and function came together.

“We thought of the warehouse as a natural feature, I said like a cliff or waterfall, that was my soundbite, but it’s true,” says Joe Spear, the lead architect of Camden Yards at what was then HOK Sport and is now Populous. “It was familiar to Baltimoreans and in terms of the city scape, its scale became an important element.” The warehouse remains the ultimate target for lefthanded sluggers. To date, Ken Griffey Jr. is the only batter to reach it, during the 1993 All-Star Home Run Derby.

Another key decision was sinking the field of play 18 feet, which dropped the outfield walls to street level and helped keep the ballpark from towering over nearby rowhouses in Otterbein, Ridgley’s Delight, and Pigtown. Fusing the warehouse with steel rather than concrete infrastructure was a creative choice, adding to the park’s throwback feel and appropriate size. The brick warehouse also served as the foundation of its classic visual composition.

“Once we had a decision to keep the warehouse, we knew the color palette of the warehouse would pretty much become the color palette of the ballpark,” Spear says. “A lot of time went into deciding the absolute best color for the brick.”

It was Smith, he says, noting her research into historic ballparks, who suggested the dark-green slatted seats, another traditional baseball look. The metal frames of the seats, stamped with the emblem of 1890s O’s star Wee Willie Keeler, furthered the pre-modern era vibe. The Oriole birds serving as weathervanes atop the scoreboard were another inspired touch. As was using the “H” and “E” in the block letters of advertisement for T-H-E S-U-N to signal a hit or error. That idea was borrowed directly from Ebbets Field’s legendary Schaefer beer sign.

When the editor of Architect asked if she could take a tour, Spear began to believe they were on to something special. They spent two hours walking around Camden Yards before he finally asked, “What do you think?” She said, “Oh, this place is totally hot. This is going to be a huge story.” He also recalls Herb Belgrad, then the Maryland Stadium Authority chairman, asking how long it would last. “I told him if we do our jobs well, fans will fall in love with it,” Spear recalls. “If the community cherishes it, then they will maintain it and that means it can last ‘indefinitely,’ like Wrigley Field and Fenway Park.”

Inspired by the success of Camden Yards, which drew 3.5 million fans in 1992, including 1.6 million out-of-town visitors who accounted for a 12 percent increase in downtown tourism, retro parks exploded across the U.S. “It put us on the map,” Spear says with a laugh, noting subsequent HOK Sports projects in Cleveland and Denver in 1994 and 1995. The gaudy attendance numbers here largely put to rest questions about the propriety of using state lottery money and state bonds for its construction. (Though not permanently. Earlier this year, the Maryland Stadium Authority told the state legislature they are seeking $1.2 billion for combined upgrades for Camden Yards and M&T Bank Stadium. The Orioles’ current lease expires in two years.)

The literal chef’s kiss was the opening of former star Boog Powell’s BBQ stand—another hit since Opening Day in 1992. Powell had the idea to do it at Memorial Stadium, but it wasn’t viable until Eutaw Street created a cozy corridor behind the right-field wall.

“We’ve had everyone from astronauts to politicians,” Powell told Baltimore a few years ago. “[William] Donald Schaefer stopped by when he was governor, and we shook hands. That was memorable for me. I was a big Donald Schaefer fan.”

The Eutaw Street utilization was critical, not just for delicious barbecue, but for everything else. It enabled home plate to be placed at the site’s south end—an unconventional distance from the park’s main entrances, by creating outfield vistas for fans as they entered, as well as the picnic area. It was while wrestling with some of the dimensions of the field that Murphy recalls receiving an unexpected letter from an older Baltimore baseball fan.

“You could tell an elderly person had written the address,” Murphy recalls. “I opened it and it was a letter from a gentleman that said Babe Ruth’s father’s saloon had been just behind second base in the outfield. We started to research it, you know, and wow, sure enough, he’s right. The building was gone, but at one point, it was there. So that added a little bit more to the sacred-ground aspects of the ballpark. You got goose bumps on your arm.

“That was kind of magical. That was kind of a cool discovery I’ll never forget.”

Or, like Camden Yards, a rediscovery.