Sports

When Bob Irsay Stole the Colts from Baltimore 40 Years Ago, A Local Cartoonist Sprang Into Action

The story behind Mike Ricigliano's larger-than-life papier mâché dummy of Baltimore public enemy No. 1—which became something of a local celebrity at parades and sports bars.

I have not any intentions of moving the goddamn team. If I did, I will tell you about it, but I’m staying here.”—Baltimore Colts owner Robert Irsay, Jan. 20, 1984

Terri Ricigliano’s two kids were not yet two years old when her husband, Sun sports cartoonist Mike Ricigliano, built a larger-than-life papier mâché dummy of Baltimore public enemy No. 1—Colts owner Robert Irsay—in their two-bedroom Cockeysville apartment.

“For whatever reason, they weren’t scared of it,” she says of her then-infant and toddler. “They seemed to like it. We were on the first floor and had sliding glass doors and I’d sit him in a chair at night like he was watching TV when ‘Ricig,’ that’s what I call him like everyone else, was at work. Sometimes, people stopped by, and I’d have to explain the whole story.”

The whole story is this: The Orioles won the 1983 World Series just as the Riciglianos arrived from Buffalo. The citywide euphoria they witnessed was short-lived, however. Five months later, the Chicago-born Irsay, who had sold his Midwestern heating and air-conditioning company to buy the Colts 12 years earlier, packed the franchise into Mayflower moving trucks. He snuck the beloved team out of town under the cover of a late-night winter squall on March 28, 1984—40 years ago this month.

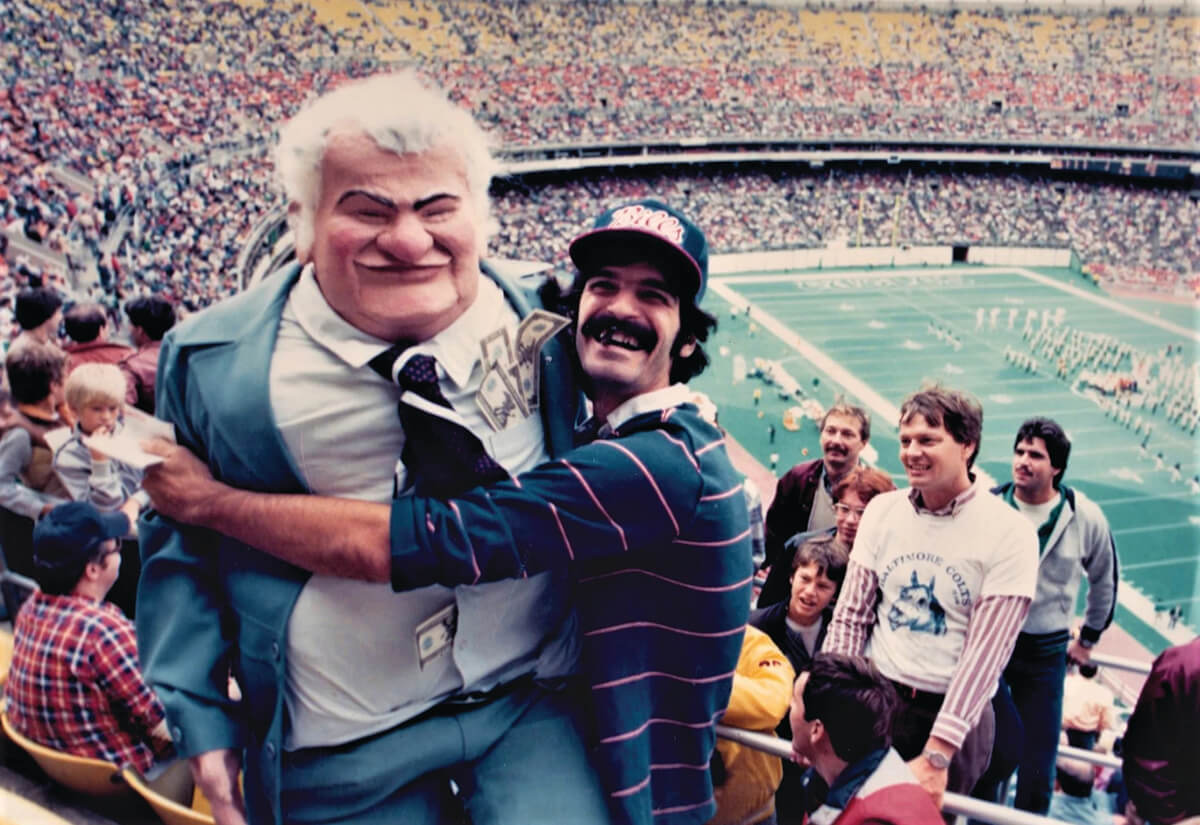

“To move here and immediately see another carpetbagging owner at work, it raised your blood pressure,” says Ricigliano, explaining the inspiration behind the dummy—and its subsequent trip to Philadelphia that fall for an early season game between the now, shockingly, Indianapolis Colts and Eagles. “His head definitely has a caricature quality, but it did in person, too,” Ricigliano adds, laughing. “It looks real because I painted its skin and put on costume hair. I got him one of those light blue suits, which Irsay wore a lot, and white patent leather shoes, which he also wore, from a Goodwill. Then, I stuffed fake money into his pocket.”

Irsay had long since destroyed the organization, turning a franchise that hadn’t had a losing season in 15 years into a perennial loser, alienating players, coaches, and fans alike by sticking his nose into football decisions. He also fabricated stories about growing up in poverty and his non-existent college football and World War II combat careers. In fact, he made his fortune after driving his own father, who’d given him a leg up in heating and air-conditioning contracting, out of business.

“I’d compare the vitriol here to the feeling we had in Buffalo for Bills owner Ralph Wilson, who didn’t live there and wouldn’t spend any money,” Ricigliano says. (When O.J. Simpson’s agent told Wilson during negotiations that his client could make the Bills a championship contender, Wilson shot back: “What good would a championship do me? All that means is everybody wants a raise.”)

On Oct. 14, 1984, several thousand Baltimore fans, many donning “Irsay Sucks” caps, rode buses up I-95 to curse Irsay in person on the Colts’ first return East. Meanwhile, Ricigliano and his wife piled the replica Irsay into their coincidentally named Colt Vista. Turned away at multiple stadium entrances, the Riciglianos were only allowed in after the daughter of the Eagles owner, a team VP, intervened. She told them they needed to buy an additional nosebleed seat for their sidekick.

After the Eagles won 16-7, photos of Ricigliano and his Irsay caricature went viral, appearing in newspapers around the country and Newsweek magazine. During the game, Baltimore fans laughed and posed for pictures with the dummy—and offered money to punch it.

Upon return, the dummy became something of a local celebrity, joining WBAL sportscaster Chris Thomas to make weekend football picks. An irreverent wit, Thomas mocked and hurled insults at the doll, which “replied” through edited tapes of inebriated public statements from the real Irsay. Over the holidays that year, the papier mâché Irsay became a regular presence at Baltimore parades, where it was generally pelted with whatever refuse happened to be nearby.

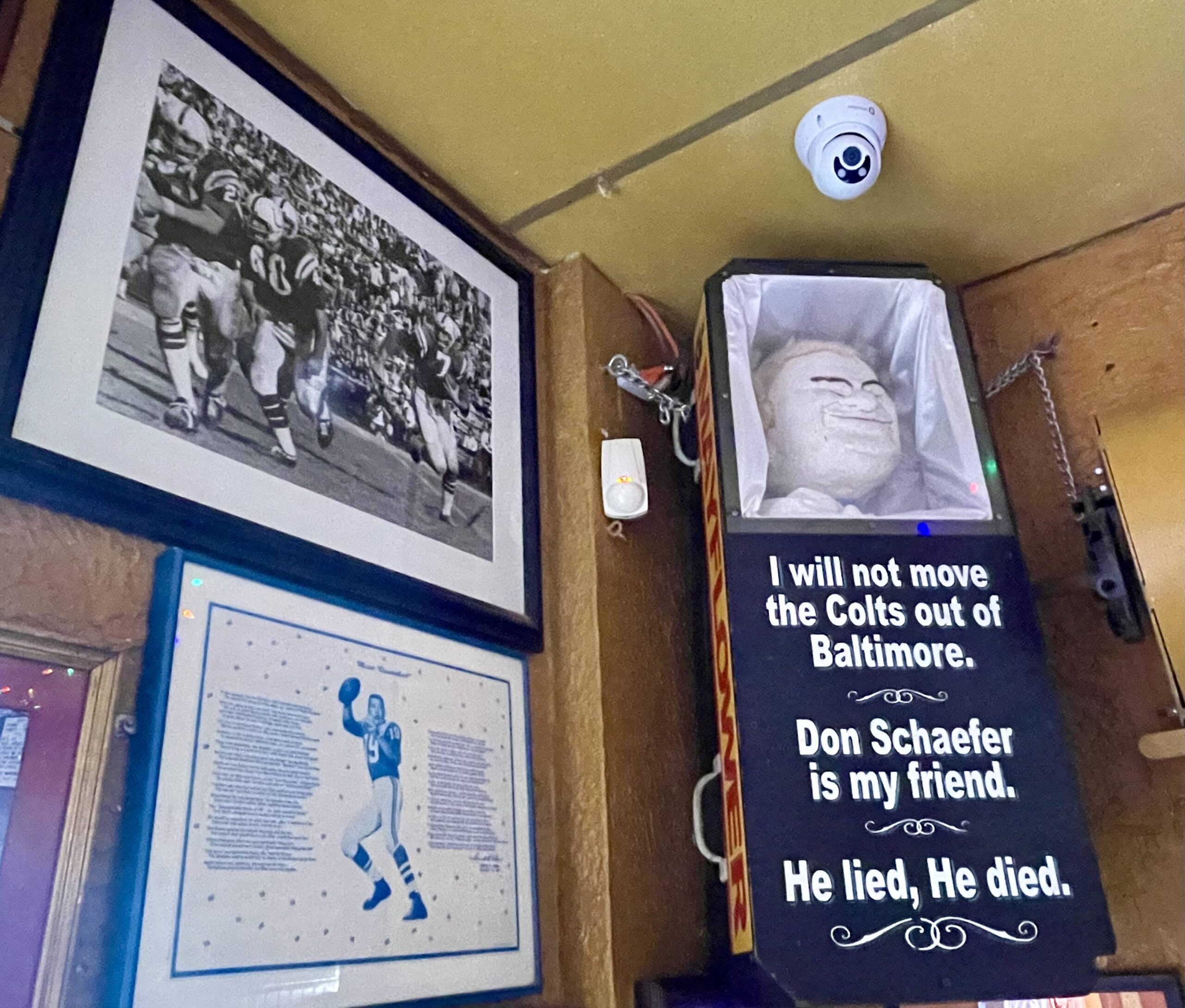

After the ’84 season, Schaefer’s Pub in Towson bid $1,400 in a charity auction for the dummy. Later, when the Bay Café opened, it moved to Canton. The dummy fared no better in the bars than on parade, however—not all wounds heal.

“I got called to repair it a few times, but it’s chicken wire and eventually there was nothing left of the body,” Ricigliano, now 72, says. “The head remains. Since the Bay Café closed, it’s sat behind the bar at Nacho Mama’s. It was a great adventure for us. I do wonder sometimes if the younger crowd there even knows who it is.”