Bird Brains

Some really smart humans are behind the Orioles’ data-friendly rebuilding project. Will they remake the Birds into a winner?

“Do you see anything?” Orioles assistant general manager Sig Mejdal asks me, looking out a second-floor window in Camden Yards’ iconic brick warehouse. He scans the empty green seats behind home plate, some 450 feet away, in search of what is essentially a medium flatscreen-TV-sized black square known as TrackMan.

“It should be right near the press box,” Mejdal says. He’s talking about the now-ubiquitous professional baseball technology that records data on every pitch thrown in every game. “I think it’s there,” he says, squinting as the mid-winter sunrays shine down from the upper deck, as we stand next to him. (This was back in January, before the COVID-19 pandemic changed everyone’s social interactions almost overnight.)

If you know anything about Mejdal’s eclectic professional background, you know the irony of this situation. In his first job out of college 30 years ago, he worked as an engineer for Lockheed Martin, tracking satellite-carrying rockets in orbit from a windowless, secure control room at a U.S. Air Force base. Many moons later, at 54, he is at his latest stop on a pioneering 15-year-long journey at the forefront of baseball’s continued data-friendly revolution. And now he can’t find his own data-tracking machine.

“Anyway, imagine a big black box up there,” he continues with a chuckle before making his broader point about how the technology has influenced the national pastime. “It has revealed information about the pitch that the human being just couldn’t pick up with our senses.”

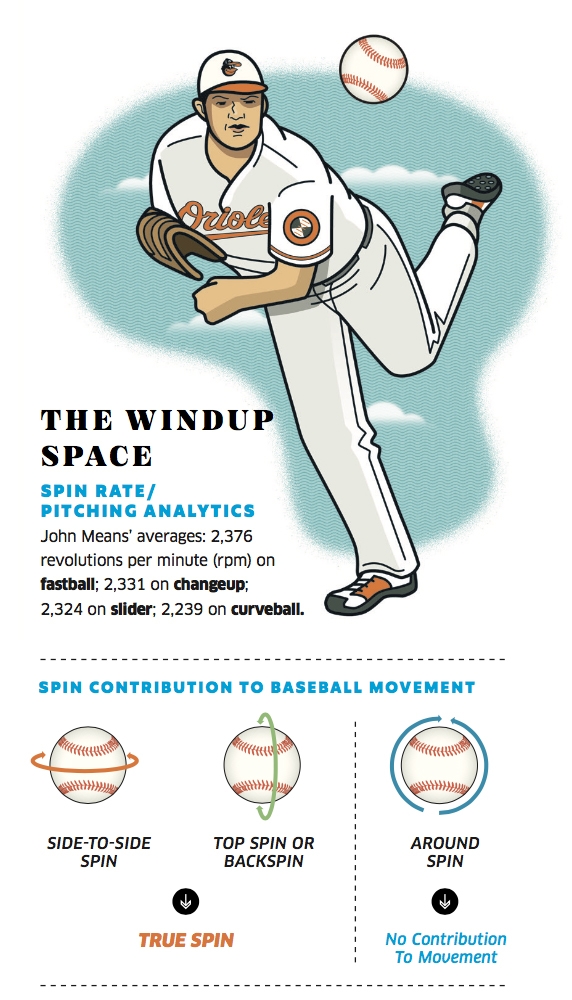

He’s not just talking about how fast the ball goes; an antiquated 1970s-style radar gun can tell anyone that. He’s talking about how fast the ball spins, measured in revolutions per minute—and how much the ball moves left, right, or down—measured in inches, on its path from the pitcher’s hand to home plate. And that’s important. Because in some ways, spin and movement are more crucial than speed.

“That’s analytics,” Means says. “It’s here, and if you’re not going to jump on board, you’re going to miss it.”

Take Orioles All-Star pitcher and Opening Day starter John Means. His ideal pitch rotates at close to 2,400 RPMs with nearly 20 inches of vertical break as it flies toward the batter in the 91-94 miles-per-hour range. Before the new breakthroughs in analytics technology, he would’ve had to rely on instinct and feel to maximize the velocity and drop of his fastball.

Today, TrackMan devices—the same ones that track golf balls during pro events—capture all the data associated with a pitch. The numbers are then paired with video of the pitch and stored in a central database that players, coaches, scouts, and front-office executives can access anytime, anywhere. Means has spent parts of the past two offseasons training with a Raspado launch monitor machine, a poor man’s TrackMan that provided just enough data for the lefty to fine-tune his motion and make sure he hit his marks. He did so again the last few months, after the pandemic abruptly ended spring training, and sent everyone home until recently.

Following a brief three-week summer training camp at Camden Yards, the O’s will open a shortened 60-game regular season on Friday in Boston against the Red Sox (in front of no fans) and their first game in Baltimore is scheduled for next Wednesday versus the Miami Marlins.

“That’s analytics,” says the 26-year-old Means, previously a career minor leaguer. “It’s here, and if you’re not going to jump on board, you’re going to miss it.”

Each of Major League Baseball’s 30 teams have analytics departments. But until recently, the broad trend of research rooted in the numbers had largely passed the Orioles by. When Mejdal and O’s second-year general manager Mike Elias were hired in November 2018 after working together for years building the Houston Astros into a championship contender, the O’s had zero staff working in analytics. Now they have 11.

Some veteran baseball execs, ex-players, and fans argue that front offices have become too reliant on the data, bending strategy to a by-the-numbers system that often ignores the human element of the sport, or that the trendy brainiacs like Mejdal and his Moneyball-like ilk are simply putting numbers to ideas that have been around for years. That’s true—to a point. O’s manager Earl Weaver, for instance, was considered innovative in the 1960s for using index cards with hitter-pitcher matchup numbers in the dugout. But today, there’s no denying the influence pure numbers-crunchers like Mejdal are having on the game.

While the richest franchises, like the Yankees, can often offer the most lucrative contracts to the most coveted players, smaller-market teams with fewer resources—Cleveland, Tampa Bay, and now the O’s— have gone a different route, emphasizing Big Data and tech startup-ish methods to help choose which players to sign, how to develop them, and, hopefully, create a sustainable winner on a smaller budget. The process can be painful for all involved. It generally starts with a team trading away any valuable pieces, like veteran pitcher Dylan Bundy and second baseman Jonathan Villar last winter, for prospects or future draft picks. And it means analyzing and molding newly arrived minor-leaguers—like 2019 No. 1 overall selection, catcher Adley Rutschman, and 2020 No. 2 overall pick, outfielder Heston Kjerstad—with cameras, data, and all the resources the front-office can think of to make them into the best players than can be.

In the short term, it also means losing a lot, like 108 times out of 162 games last season, thus the ability to pick high in following year’s draft. Just based on the length of this pandemic-shortened, 60-game regular season about to begin, it’s impossible for the O’s to lose that many games in 2020, but the point remains that the organization in the early stages of a rebuilding process.

“There’s a lot of nights where it’s not easy,” O’s second-year manager Brandon Hyde says, “but you just have to really think about the big picture, that things will work out in the end.”

The tear-it-down-to-the-studs approach is not without its detractors. “Old-school guys have always used numbers and information to come up with a plan to play,” former O’s infielder and Emmy-winning MLB Network commentator Billy Ripken says. What’s often lost in the new-age narrative, though, is that analytics represent just one (big) piece of the lose-now, win-later team-building concept. Traditional scouting, guys in the stands observing games and interviewing players and people close to them, is still part of the story.

After all, reliable numbers are harder to gather when you’re analyzing teenagers in places like the Caribbean. That’s where Elias, back in 2010—then working as a scout for the Astros—first saw future star shortstop Carlos Correa as a 15-year-old, standing out among boys and men much older. Elias stumped for Correa and was the driving force behind the Astros selecting the future World Series star with the No. 1 overall pick in the 2012 MLB Draft. To what degree seeing-eye scouts’ voices are heard or weighted in today’s game—versus analytics—is debated and can vary by team. Just know that in Houston, in order to heal this apparent new school vs. old school culture clash, Mejdal created a metric called “Stouts”—half statistics, half scouts—using information from both.

The data-driven ideas have worked more than once for recent championship contenders, including Chicago, where Hyde was part of a rebuilding project that at times looked bleak but culminated in the Cubs’ first World Series title in 108 years. The same goes for Houston, where Mejdal and Elias had previously worked together since 2011—as director of decision sciences (real title) and director of amateur scouting, respectively. They helped the Astros transform from three seasons of 100-plus losses to a playoff contender in two years. (That also means they were there during Houston’s now-controversial 2017 championship season. Neither was mentioned in MLB’s disciplinary report on the team’s sign-stealing operation. Elias told us, “It’s an issue that I’m glad baseball is rectifying,” while Mejdal said he finds the admissions from the Astros “disturbing.”)

Elias, the leader of this whole data-friendly rebuild, actually told us, “I’m not an analytics person,” but you have to understand the context of the Orioles general manager’s statement when he says it. Scouting has been Elias’ forte during his 13 years working in baseball. When he became the O’s top personnel executive at 35, one of his first decisions was to hire an international scouting director (Koby Perez from Cleveland) and strengthen the team’s presence in Latin America with scouts and new facilities. This summer, the team signed a record 27 international amateur prospects to deals in one day.

But Elias is longtime friends with Sig, and he’s certainly familiar with the geeky narratives that have been part of baseball since the early 2000s, when the then-unique, on-a-budget approach of the small market Oakland Athletics was chronicled in Michael Lewis’ landmark book, Moneyball.

“The first wave of analytics, 15 years ago, was about using stats to find predictive information, about what the player was going to do next,” Elias says. “What’s new in the last five years is we have tons of new technologies that measure the physics of the sport—the ball in flight, the spin, speed, and location, and also what the bat is doing, and what the player is doing on the field. In the same way that we analyzed statistics 15 years ago, we’re trying to gain an understanding of which of these properties matter and what they mean.” This could mean helping pitcher tweak their release point or ensuring a hitter is swinging on his most effective plane.

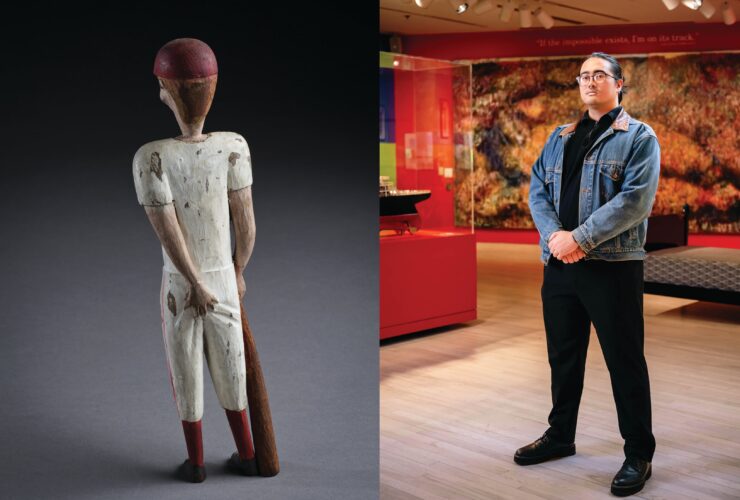

The son of a former U.S. Secret Service officer, Elias went to Yale, where he injured his pitching shoulder and then got an internship with the Philadelphia Phillies that led to his first scouting job with St. Louis in 2007. That’s when he met Mejdal, who had been working for the Cardinals organization for a few years. After tracking those satellites, Mejdal had held jobs at former internet search-engine giant AltaVista and as a sleep scientist for NASA. But after reading Moneyball in 2003, at 37, Mejdal thought there might be a place in the game for someone like him. As a kid growing up in California, the son of immigrants who met in the U.S. Army, he loved math as much as Little League.

“I remember learning fractions in grade school and getting excited,” he says. “If Hank Aaron has seven homers after 29 games, you could figure out how many homers he will have after 162.”

The Orioles’ version is called Omar. “It’s a reference to the character from The Wire,” Elias confirms. “It also starts with an ‘O,’ which is nice.”

The Orioles surprise All-Star selection last season was Means, an 11th-round pick who has worked hard—and smart—to cultivate the downward trajectory of his fastball and says he’s a “math guy” like Mejdal. When the Orioles injected Astros blood into their front office, Means figured he should get with the program. It’s too simple to chalk up the former career minor-leaguer’s improvement to one thing, but he believes the utilization of new technology and analytics was a key reason he cracked the O’s 2019 roster and became an All-Star.

Data and “hit maps” – that show where players tend to hit the ball and against which kind of pitches (fastballs, curves, sliders) they are most successful—have also given rise to ugly-looking defensive schemes, like shifting a shortstop somewhere to the short right field when a pull hitter like Chris Davis is at bat.

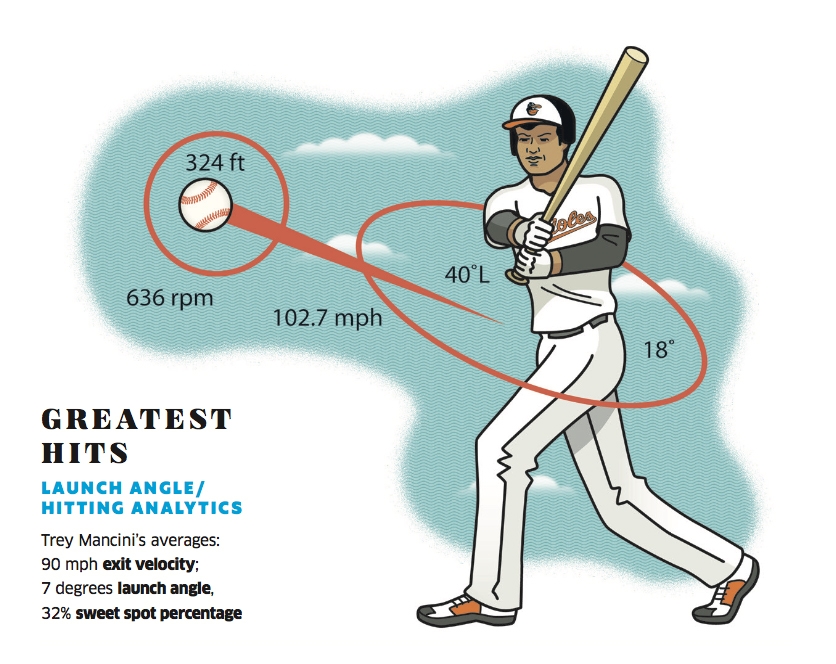

But there’s other new technology, including sensors that track bat movements, which may help hitters even the score. There’s also new wearable technology, including the K-Vest, which Trey Mancini, the O’s top slugger who remains away from the team while undergoing treatment for colon cancer, experimented with toward the end of 2019. The K-Vest essentially tells a hitter everything he would want to know about how his hips, arms, legs, and torso move when he swings the bat. “The kinematic sequence,” Mejdal says. “There’s a chance this might be the breakthrough for hitting.”

All of this data is stored in a centralized database. The Astros called theirs Ground Control—a nod to Houston’s history with NASA. Elias’ wife, Alexandra, who works in marketing, suggested the name. The Orioles’ version is Omar. “It’s a reference to the famous character from The Wire,” Elias confirms. “And it also starts with an O, which is nice.”

A manager in the analytics department, Baltimore native Di Zou, the lone analytics staff holdover from the Dan Duquette-Buck Showalter era, picked the name, as well as its official title: Orioles Management and Analytics Repository.

Via a password-protected, web-based dashboard not unlike many companies’ boring human-resources portal, players, coaches, scouts, and front-office people can log into Omar and access information that would be catnip for the serious fan.

“I can pull up video from any at-bat I’ve ever had in the majors or minors, to a certain degree,” Mancini told us earlier this year. Means can track that critical downward break on his fastball. And Hyde can pick out the meaningful nuggets, like to predict how versatile hitter Hanser Alberto might fare against a particular pitcher, or a tweak that outfielder Anthony Santander could make defensively.

But Hyde says an important part of his job is also filtering what he shares, depending on the player. It’s a balancing act of old school and new school that will continue to evolve.

“Analytics is such a broad word that means so many different things,” Hyde says. “The best coaches describe the data and understand what’s going to work for each individual player. That’s part of coaching, not forcing things down their throats, but understanding who can handle what.”

To that point, Mejdal admits he is sometimes asked what might be considered a blasphemous question around the Orioles offices these days. Is there such a thing as information overload? Mejdal laughs, like he’s heard this one before.

“Information overload?” he says, almost incredulous. “More is better. That’s the thing here.” Now they just have to find what they’re looking for.

Baby Birds

You’ve heard of Trey Mancini and John Means, but the Orioles’ other guys? Not so much. Here’s a few new faces to look for this season.

AUSTIN HAYS, OF

Hays shined after being called up last September. The 24-year-old batted an impressive .309 and showed strong defensive skills. He could be the Orioles centerfielder for years to come. “If I continue to work hard and progress,” Hays said during the O’s summer training camp last week, “I have a lot of confidence I can continue to prove myself at this level.”

RYAN MOUNTCASTLE, INF/OF

The soft-spoken 23-year-old is one of the best hitters in the minor leagues. If the 6-foot-3, 195-pounder can find a home in the field, expect to see him at Camden Yards in 2020.

ADLEY RUTSCHMAN, C

The No. 1 overall pick in the 2019 draft may get to the majors quickly. He got promoted up in the minor league ranks twice in roughly a month last summer. “We’re excited to have him,” Elias says. “He knows what it takes to lead a team and how to make himself better.” Another indicator of Rutschman’s star power: He was stalked by TMZ at the airport upon arrival in Baltimore.