Sports

Staying Power

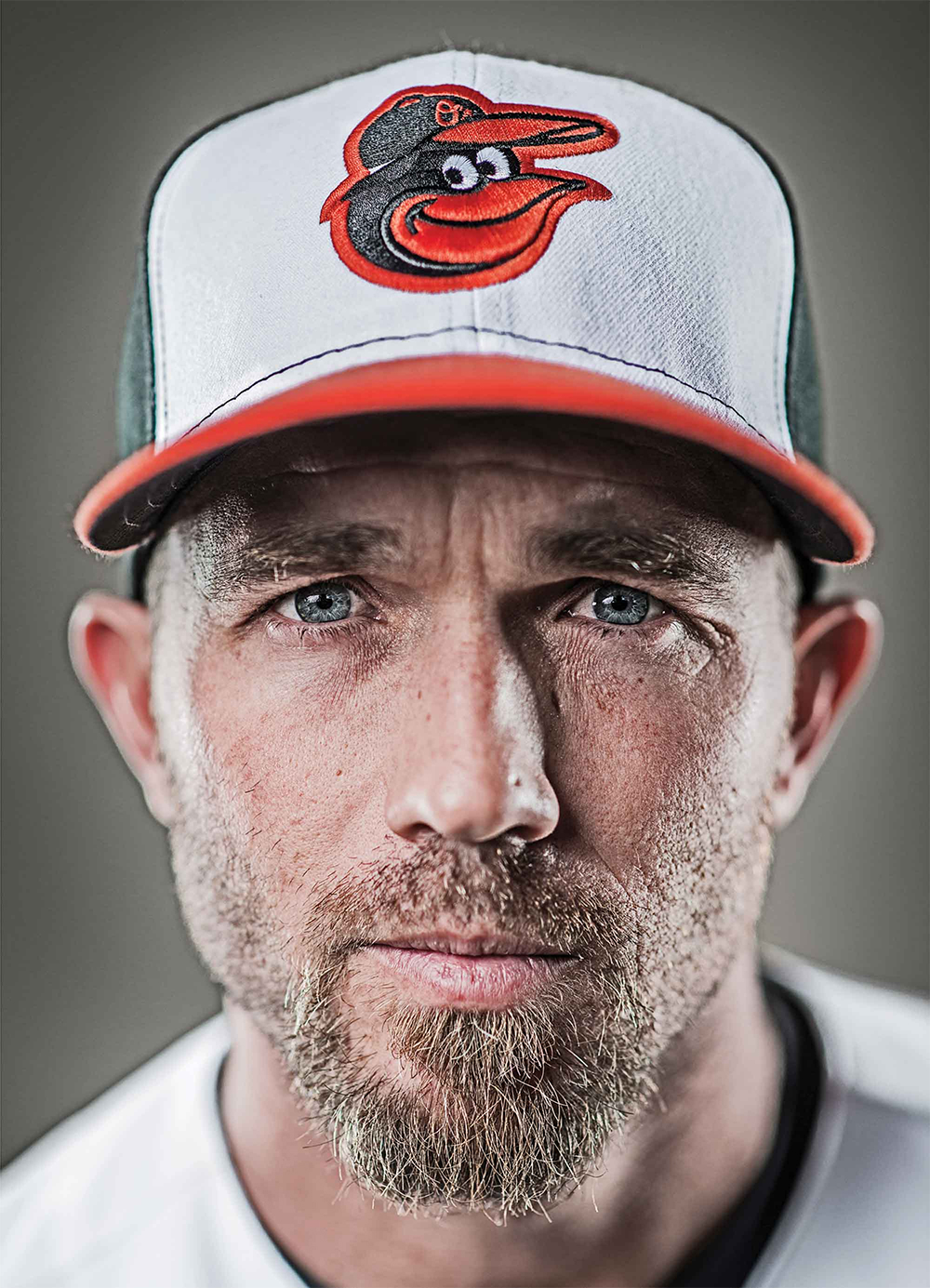

J.J. Hardy has cemented himself as one of the most reliable players in Orioles history.

Back before James Jerry Hardy became “J . . . J . . . HARDY!” his father, Mark, wanted to get him into a T-ball league. J, as his dad calls him, was just 4 years old at the time.

“While we were signing him up, he and his brother, Logan, were playing catch with a hardball,” Mark recalls. “People freaked out. They ran over and took the ball away because it was too dangerous. But the boys had been playing catch like that for a year, probably. So he was a little ahead of most of the kids.”

Nearly three decades later, he’s still ahead. Baltimore’s best shortstop since Cal Ripken Jr., Hardy won his third straight Gold Glove last year. After an offseason that was mired by attention on key free agents the Orioles didn’t re-sign, it’s important to remember the one they did. In October, on the eve of the franchise’s first appearance in the American League Championship Series in 17 years, Hardy agreed to a three-year, $40-million contract extension.

“I couldn’t imagine our team without J.J.,” Orioles manager Buck Showalter says. “He’s a guy who makes a lot of things work for us. J.J.’s very much like Baltimore—not a lot of bells and whistles. You always look for someone, especially in Baltimore, who you can count on. J.J.’s like that—you know what you’re going to get from him every day. I think there are a lot of people who still don’t quite get how good he is, but we do, and that’s one of the reasons we signed him.”

A natural-born athlete from a family full of them, Hardy can beat you with his glove, his bat, and, as the Detroit Tigers found out in last season’s ALDS, even his legs. His easy-going, outwardly laid-back manner belies a fierce competitor whose preparation is unparalleled. It’s that consistent, day-in-and-day-out approach to the game that has established a mutual respect and admiration between player and city. (Remind you of any other O’s shortstop?)

At FanFest in January, cheers for the 6-foot-1, 32-year-old Arizona native with Brady Anderson-esque sideburns, deep blue eyes, and plenty of product in his hair were a bit higher-pitched than those his teammates received. When he walked to the plate during the playoffs three months earlier, the love affair was on display for all to hear. Camden Yards public address announcer Ryan Wagner, whose first-game jitters in 2012 accidentally led to the rhythmic delivery of what’s become his signature call, let the fans finish what he started.

“Now batting for the Orioles, shortstop, No. 2 . . .

“J . . . J . . . HARDY!” the crowd chanted with him.

“That first at-bat during the postseason gave me the chills,” Hardy says. “The second at-bat I was kind of listening for it, and it was even a little bit louder. Everybody on the other team and our team were telling me how cool it was. They didn’t have to tell me. I thought it was pretty darn cool.”

If athletic ability alone were a sure-fire predictor of success in professional sports, J.J. wouldn’t be the only Hardy to have made it big in the sports world. His father is a tennis pro at La Paloma Country Club in Tucson, AZ, where Hardy grew up. His mother, Susie, was the No. 1 golfer at the University of Arizona and one of the top amateurs in the nation. His sister, Jessica, played volleyball, golf, and attended college on a tennis scholarship. His grandfather, Jerry Shinn, had a tryout with the New York Yankees, and his uncle, Jerry Jr., was offered one with the Dallas Cowboys.

“He’s not looking to make a fancy play. He wants to make every play.”

But in this family of all-stars, Hardy’s most significant influence was his big brother, who set his sights on the military.

“We were pretty competitive,” says Logan, 17 months Hardy’s senior. “Everything we did was trying to beat the other person. We never did anything just for fun. There were a few fistfights. They were draws. Mom always broke it up before we could get into it.”

The boys played everything together: soccer, tennis, racquetball, golf. (Hardy’s Ping-Pong prowess is legendary around the Orioles clubhouse.) But baseball was Hardy’s favorite, or at least it became that when his ability started to crystallize. When he was 9, officials defied the eligibility rules to allow him to play Little League with 10- to 12-year-olds. As a high-school sophomore, he played on select teams, and, by his senior year, so many scouts were pointing radar guns at him that Mark joked, “I thought he was going to get cancer.”

Pro teams (and college coaches) salivated over the thought of signing a player with a major-league-ready arm that he displayed both at shortstop and on the pitching mound.

Mark, who played baseball in junior high, was Hardy’s de facto pitching coach. He utilized principles he learned from tennis to craft his son’s unique over-the-top throwing motion, which Hardy still employs today.

“The serving motion and the throwing motion are almost identical,” Mark says. “What I tried to do with J was get him to understand spin early. I took a baseball and used a marker and painted half of it black. We practiced throwing so he could keep the black on one side. It wouldn’t rotate. He’d come right over the top and throw a four-seamer that was just dead straight.”

Most of the time. During one of the opening games of his senior season in high school, Hardy made a throwing error and went 0-3 at the plate. He counted at least 30 pro scouts in the stands, and he was nervous.

But Hardy’s mental toughness, forged through the constant competitions within his family, and his even-keel nature allowed him to shake off bad performances like that and focus on the next play, next at-bat, or next outing on the mound. He was selected by the Milwaukee Brewers in the second round of the 2001 draft, signed about a month later, and embarked on a career that appeared fast-tracked for the big leagues until he took an awkward swing at an inside-fastball during a minor-league game in 2004. Suddenly, everything was a question mark.

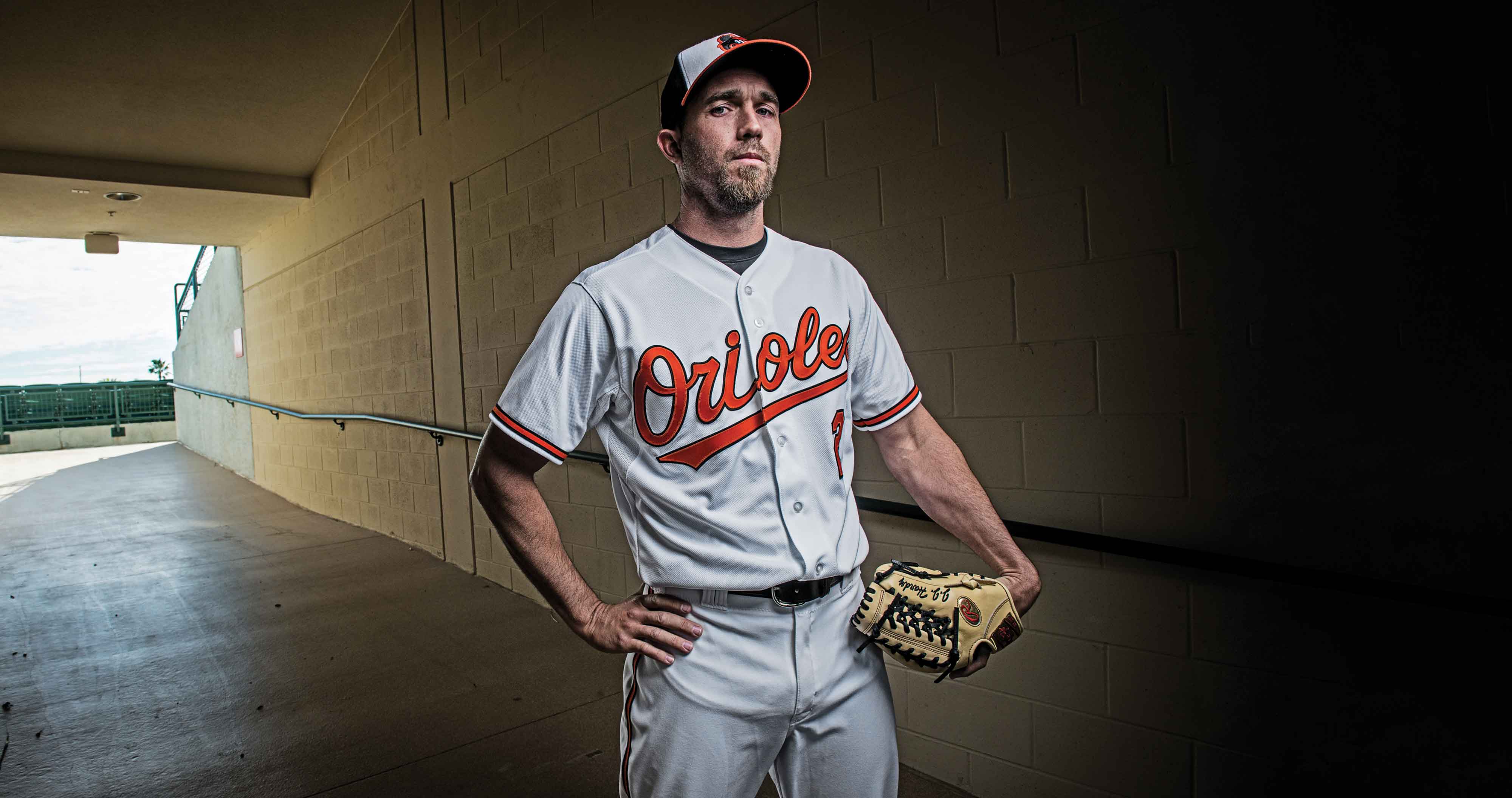

J.J. Hardy poses with his award-winning glove in Sarasota, FL. —Photography by Josh Ritchie

Ironically, the biggest setback in his career came against an Orioles farm team. The cut Hardy took against the Orioles’ then-AAA affiliate Ottawa ripped his shoulder from its socket. He had torn his labrum, ending his season. Stashed on the disabled list, he moved into a house in Tempe, AZ, where he did a whole lot of . . . nothing.

“I went into kind of a depression,” he admits. “I was thinking 2004 was the year I was going to get called up [to the major leagues]. The injury wasn’t a real normal injury. [I worried], ‘Is this a career-ending type of thing? Am I not going to get my shot?’”

Meanwhile, Hardy’s brother, Logan, was battling his own demons. A radio operator with the U.S. Army’s 75th Field Artillery Brigade, he crossed into Iraq the day the war began. His tour had taken an immense toll on him, and, when he returned home three years later, he suffered from post-traumatic stress disorder, or PTSD. He was unemployed and living with his parents when they suggested, forcefully, that he move in with his brother.

For the first few weeks, the new roommates rarely spoke to one another, both grappling with their new realities. They’d lounge on the couch with the lights off and stare at the TV, even when it wasn’t on. Every now and then, they’d venture out to sit in silence in the hot tub. “I felt like I was going nowhere,” Logan says. “I looked at him and he felt the same way.”

Hardy gave Logan the space he needed, and soon he began talking about his experiences in the war and the frustrations he was dealing with at home. Hearing about his brother’s struggles provided Hardy with a different perspective on life.

“Once he started talking, I think he started to get a little bit better,” Hardy says. “But I got better instantly when I realized, ‘Why am I in such a depression when he went through what he did?’”

Rededicated to his physical rehabilitation, Hardy worked his way back and was the Brewers’ starting shortstop on opening day 2005. (He went 1-4 with 2 RBIs in his major league debut.) It was the start of a five-year run in Milwaukee, during which he developed into one of the team’s most popular players.

Logan’s revival, while slower, also proved successful. Today he manages a garage-door company and lives in that same house in Tempe, where he catches as many Orioles games as he can. The lights are on much more often these days.

In the midst of a breakout 2007 season in which he hit 26 homers, Hardy started watching the Women’s College World Series in the Milwaukee clubhouse.

He watched one woman in particular.

“I remember seeing the right fielder come to bat and thinking she was cute,” he says. “So I got a couple of my teammates to watch. The next time she came up I go, ‘Hey, what do you think?’”

The Brew Crew approved of Adrienne Acton, as did Milwaukee manager Ned Yost, who had wandered out of his office and now was urging Hardy to call the University of Arizona outfielder. He contacted his cousin, also a student there, who got her number through a mutual friend.

“The whole team was involved, so I had a lot of pressure,” he says. “So I called her, and I say, ‘Hey, it’s J.J.’ She says, ‘Who?’ I say, ‘J.J. Hardy.’ She says, ‘Who?’ I straight panicked. She didn’t know I was calling. I hung up the phone right there and was thinking how I was going tell all my teammates and Ned that I screwed it up on the first phone call. An hour or two later I texted her and said, ‘Sorry, I thought you knew I was going to call.’ She was like, ‘I didn’t know, but I’m glad you did.’ We talked for a month, and then I flew her out to Milwaukee and that was the first time we met.”

Married in December 2013, they share a love for being active and the outdoors. So much so that they spent their first wedding anniversary apart. He hunted elk in New Mexico while she snowboarded with friends in Montana.

“We celebrated a couple of weeks later in Park City,” he says, “so we didn’t get in a fight on our first anniversary.”

After a solid 2008 season, Hardy slumped and was even sent back to the minors. He was traded to Minnesota before the 2010 season, and to the Orioles a year later.

“When I came over, I remember thinking, ‘Man, there is a ton of talent,’” he says of Baltimore. “The pitchers all had great arms. We just weren’t real consistent. You could kind of see that light at the end of the tunnel. I think Buck has a lot to do with it.”

“it’s nice to know that i’m going to be here for a few more years.”

Ask Hardy about the managers he’s played for and he’ll say there have been plenty of good ones. But he’s unapologetic about naming his favorite. Listening to the two talk about one another, it’s clear why the sides were able to work out a contract extension before Hardy made it to the open market.

“He is the most prepared man I’ve ever been around,” Hardy says of Showalter. “If you have a conversation with him, you have the feeling that he knows how the conversation’s going to go. If he asks you a question, he knows the answer already and is just curious what you’re going to say.”

Or is it the other way around?

“J.J.’s very detail-oriented,” Showalter says. “He takes a lot of pride in it. I would not have brought Manny Machado and Jonathan Schoop to the big leagues as early as we did if we didn’t have J.J. Hardy. He’s such a great example for those guys, and they look up to him. He’s like having another coach on the field. In advance meetings, he’ll make a suggestion on positioning on bunt defense or a relay. You go, ‘Any questions on this?’ Trust me, if he raises his hand, you better have a good answer.”

Hardy hit 77 homers in his first three seasons in Baltimore, and won the Gold Glove his past three. Watching him play has been a joy for former Oriole Mike Bordick, Baltimore’s stellar shortstop from 1997 to 2002.

“He’s like a zen defender,” says Bordick, now an analyst with MASN. “He has great instincts. What separates him from others, when you watch his feet, are the little moves he makes to get the best hop possible. He makes the ‘wow’ plays, but he makes the consistent plays more often. He doesn’t do extra stuff unless the ball takes him to a position where he has to. He’s not looking to make a fancy play—he wants to make every play.”

Showalter concurs. “You see guys with all the flash making the SportsCenter plays of the night, and J.J. will make that same play without the flair,” he says. “His flair is consistency. A ball will take a bad hop and he will make the adjustment with his hands and we’ll look at each other and say, ‘Did you see that?’ If I was at Baseball Tonight, I would have J.J. on there every night. He’s made a couple of tag plays on stolen bases that people can’t make. He’ll catch the ball going down instead of going up on a short hop. It’s impossible. Try doing that in your backyard.”

Orioles announcer Ryan Wagner explains the origins of the J.J. Hardy call.

Orioles announcer Ryan Wagner explains the origins of the J.J. Hardy call.

For all the praise heaped on Hardy for his glove and his bat, his most magical Orioles moment came in Game 2 of last year’s playoff series against Detroit, when he scored what turned out to be the winning run on Delmon Young’s double off Tigers pitcher Joakim Soria.

“When he hit that ball, I put my head down and took off,” he says. “I don’t know if I was going fast or not, but I was going as fast as I could go.”

Surprised when third-base coach Bobby Dickerson waved him home, Hardy reached his left hand under the tag, leapt to his feet, and smacked his palms together as Camden Yards exploded.

“When people ask about the biggest memory from that season, that was it,” he says. “I don’t think I’ve ever heard a place that loud. Joakim Soria works out where I work out. He told me, ‘That stadium’s just too loud.’ It was pretty cool hearing it from the other team’s perspective.”

Comfortable in Baltimore playing for a manager he loves and fans who have embraced him, Hardy chose to forgo free agency during a year when a certain division rival was looking to replace its own retiring shortstop, Derek Jeter (who also wore the No. 2).

Hardy undoubtedly would have had a number of potential suitors had he made it to the open market, and the Bronx Bombers certainly would have been one of them. The idea prompts a chuckle from Dan Duquette, the Orioles executive vice president of baseball operations.

“Well, the Yankees like veteran, proven, major-league players, and they were in the market for a replacement for their longtime shortstop, so it could very well have been a possibility,” Duquette says with a smile.

For his part, Hardy is happy that the offseason process is over.

“There are a lot of unknowns in free agency, so I’m glad that I didn’t have to deal with any of that,” he says. “It’s nice to know that I’m going to be here for a few more years. I knew that I liked playing with the Orioles. I’d like to have a chance to win the World Series before my career is over, and I feel like there’s going to be more opportunity [here] to get back to the playoffs.”

Staying with the same team makes a lot of sense for a guy who thrives off consistency, the likes of which hasn’t been seen since the Ripken days. In fact, when Hardy trotted out to the sacred ground between second and third base during his O’s debut in April 2011, he became Baltimore’s sixth different opening day shortstop since 2001, the year of Ripken’s retirement.

Orioles fans finally have another steady one to root for whose name they won’t soon forget.