Sports

Johnny Unitas Threw His First NFL Pass 60 Years Ago

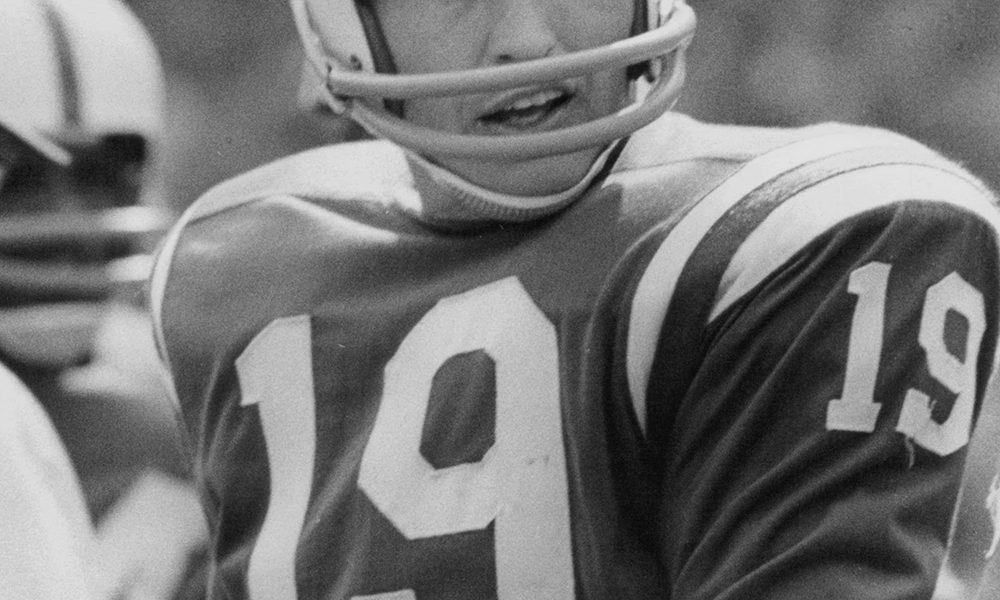

Even now the aura of No. 19 permeates the entire metropolitan area.

Six decades ago—right about this time of the year back in 1956—an unknown rookie quarterback named Johnny Unitas walked onto the gridiron of Baltimore’s consciousness.

And he never left. Not today, some 14 years after his death nor more than 30 after the team with which he is synonymous—the famed and fabled Baltimore Colts—quit town for some obscure Midwestern burg.

Unitas was perfectly in tune with the psyche of the unsung factory town on the Patapsco in which he set records, won trophies, and made lifelong friends.

“I came into the league without any fuss. I’d just as soon leave it that way,” he said upon leaving the game in 1973 en-route to the Hall of Fame. “There’s no difference I can see in retiring from pro football or quitting a job at the Pennsy Railroad. I did something I wanted to do and went as far as I could go.”

Unitas’s debut in 1956—the tectonic plates of American football about to shift though no one knew it—has been dramatically misremembered for decades. Even Unitas was wrong, going to his grave in 2002 believing it had been one way when it was another.

Jim “Snuffy” Smith, 73, a longtime Baltimore area basketball coach and fervent fan of all Crabtown sports, tells it like this.

“I was 13 and watching the Colts play the Bears at Wrigley Field. The Colts weren’t good yet,” said Smith of the game, in which Chicago crushes Baltimore 58 to 27. In that game, starting quarterback George Shaw broke his leg and out came a young Lithuanian-Catholic from Pittsburgh wearing No. 19, his scrawny right arm not yet cast in gold.

“Unitas was forced into the game and we didn’t know a thing about him, a skinny kid with stooped shoulders who walked like an 80-year-old man,” said Smith. “His first pass was intercepted for a touchdown and the rest is history.”

Yes, history, lots of it. Unitas quarterbacked the Colts victory over the New York Giants in the 1958 “Greatest Game Ever Played” championship and was a member of two other Baltimore title teams.

But Smith’s version history—the same one Unitas believed up until his fatal heart attack—jumps the gun by two games.

In 2006, veteran Baltimore Sun reporter Mike Klingaman set the record straight, pointing out that the first time the locals got a glimpse of Unitas under center was not via television from Chicago on October 21, but in front of 42,622 fans at Memorial Stadium on October 6.

The Colts lost that game as well, 31 to 14 to Detroit. But Johnny U was launched, right about the time Brooks Robinson was going gold at third base for baseball’s Orioles, and Baltimore would never be the same.

Late in the life of Johnny Unitas, the children from his second marriage played a lot of community and school sports in and around Baltimore County. At one lacrosse game in the 1990s, Hampden resident Joe Mooney had a daughter in a game against a member of the Unitas progeny.

Mooney grew up going to Colts games with his parents in the 1960s and, like thousands of other kids back then, had Johnny U’s autograph and pictures on his bedroom wall.

“He was critical of the refs whenever he felt like it,” said Mooney, 63. “All I could think of was, ‘What must that be like for [a small-time] lacrosse refs to get chewed out by Johnny Unitas?’”

After the game, Mooney walked over to the other team’s side and asked if he could shake the hand that had thrown 290 touchdowns in an 18-year professional career, all but one of them in Baltimore.

Remembers Mooney: “I said, ‘Do you mind?’ And he said, ‘Not at all.’”

The hand that Mooney shook was the first to throw for more than 40,000 career yards. In 1959, he set a record with 32 touchdowns, the first to throw more than 30 in a season. Between 1956 and 1960, he threw a touchdown in 47 consecutive games, a feat once compared to Joe DiMaggio’s 56-game hitting streak.

All of those National Football League statistics have been broken by bigger and faster athletes who now play 16-game seasons and are aided by rules designed to protect the quarterback from injury.

Yet the aura of Unitas permeate the metropolitan area not unlike, we daresay, that of Babe Ruth.

From the Beltway sign announcing the exit for “Unitas Stadium” at Towson University to the statue of Unitas outside of M&T Bank Stadium to the flurry of blue and white No. 19 jerseys at Ravens’ home games, he is here.

“He’s the foundation of Ravens football,” said Jimmy Rupert, a 30-year-old Pasadena realtor born the year after the Colts left town. “Growing up watching football with my father and grandfather that’s all I ever heard about—Johnny Unitas, the guy who put up the big numbers.”

Rupert goes to at least two Ravens games a year, sometimes more. Before each game, he joins fellow pigskin pilgrims in touching the one of the Johnny U statue’s high-topped cleats, now discolored from years of the tradition.

He does it, he said, “For good luck.”