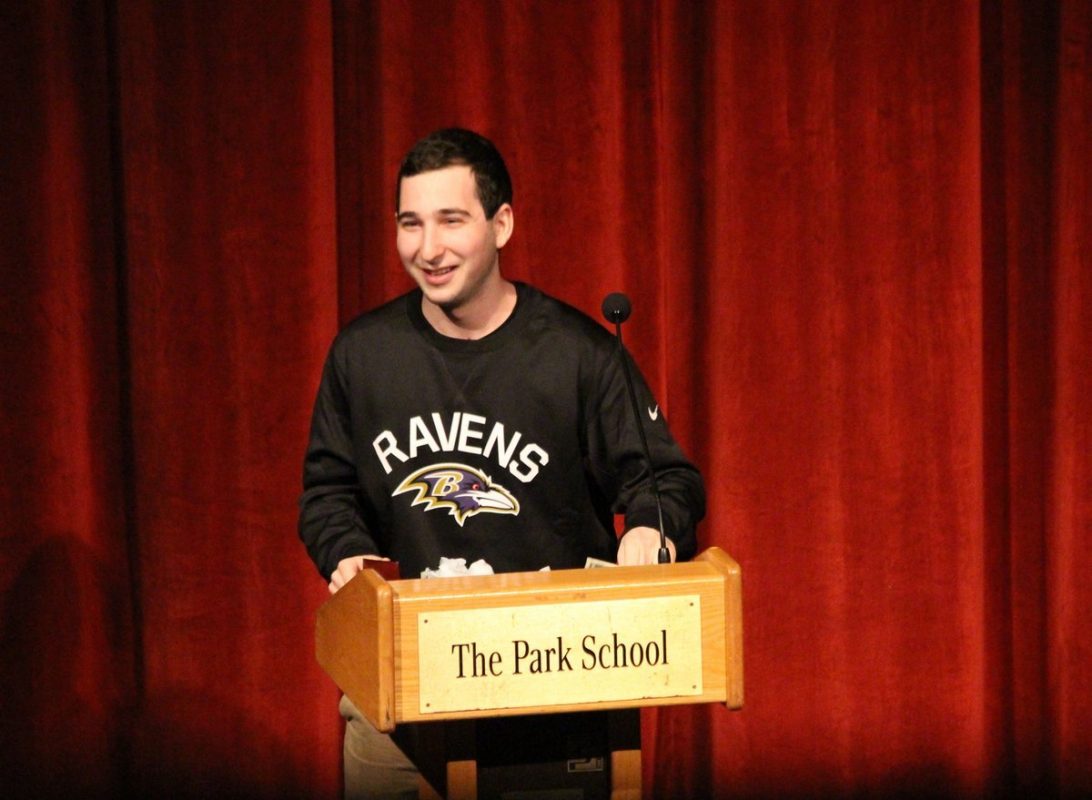

On an April weekday morning near the end of his senior year of high school, Daniel Stern stood behind a podium in a crowded, wood-paneled Annapolis courtroom, wearing a gray suit and a purple shirt-and-tie combination as he emphatically pleaded his case. The skinny, super-articulate, high-achieving kid from suburban Baltimore wasn’t in trouble; far from it. Representing a fictional state prosecuting team from the private Park School in Pikesville, the then-18-year-old was delivering the closing argument in the championship of the 2012 Maryland state mock trial competition.

The case: State of Maryland vs. Drew Hunter, an imagined coach of a girls’ high school soccer team who, Stern argued to a panel of three adult judges, caused three players to suffer heat exhaustion during a hot, late morning practice in August. “One of them is still in the hospital!” he said, making the situation sound as real as possible. This coach, Stern said with the flair of a seasoned trial lawyer twice his age, should be found guilty of reckless endangerment and child abuse.

“This is a case about a coach who made bad decision, after bad decision, after bad decision,” Stern told the court, while laying out the facts of the case: Players were instructed to run in sprints in 104 degree heat, in a practice that lasted more than two hours, and the coach was slow to react when players collapsed. “We’ve proven it beyond a reasonable doubt.”

The performance was convincing, room-owning, and vintage Daniel. He’d been the closer since freshman year. “He’s a very intense guy and he’s very passionate about whatever it is he’s doing,” says Tony Asdourian, one of Stern’s former teachers at the Park School and an assistant coach on that mock trial team. “That was true very much that day.” (The 13-member team won its second straight state title.)

Stern couldn’t have known it then, as a high school whiz kid a few months from graduation and bound for Yale University, where he’d lead two national championship mock trial teams, but the words he spoke—bad decision, after bad decision—are almost comically fitting given what Stern is doing nearly eight years later. He’s not a lawyer, but he is paid to use his analytical and lawyerly abilities, in sports. And in his hometown no less—in a job ensuring that Ravens coach John Harbaugh has all the information necessary to make good decisions during football games.

At age 25, the Baltimore kid in his fourth year working for the team of his youth. He joined the Ravens immediately after he graduated from Yale in 2016 with a degree in cognitive science, a major that can essentially prepare you for many professions. Today, Stern’s official title is football analyst, and he’s part of a handful of staffers in the Ravens’ analytics department led by director of football research Scott Cohen. (The Orioles aren’t the only number-friendly pro sports team in town.)

Stern’s title leaves room for interpretation, but in the context of this spectacular Ravens season—after beating the Steelers yesterday, they’re now 14-2 and remain the odds-on favorite to win the Super Bowl as the playoffs begin—the scope of his largely unheralded contributions has emerged more visibly.

During every game, the boy wonder sits in a chair right next to Ravens offensive coordinator Greg Roman in the weather-proof coaches’ level of the stadium. And like a play caller, Stern wears team-issued apparel and one of those big black Bose headsets with a direct line of communication down to the field to Harbaugh. The head coach always makes the final decisions, but Stern notably has Harbaugh’s ear, quickly and clearly relaying “the numbers”— the so-called win probabilities and risk-reward ratios of certain situations.

For years, Harbaugh has had a staffer in the booth in this role. At first, it was Matt Weiss, who is now the team’s running backs’ coach. Stern took over the job this season, and what he does informs some of Harbaugh’s key game-management decisions—including whether to go for it on fourth down, which has become one of the calling cards of this Lamar Jackson-led, “Big Truss”-infused team.

A fourth-down try, for instance, if it fails, gives the opposing team great field position of their own, and NFL coaches have traditionally hesitated to take the risk or make it simply on gut feel. But with careful, deliberate planning done throughout the week, very specific data provided by Stern on-the-fly on game day, and players like Jackson making things easier and also giving their own input, (As in, “Hell yeah, coach! Let’s go for it,” before a fourth-and-2 earlier this year against the Seattle Seahawks), the Ravens have noticeably bucked the conservative nature of their competition.

They’ve converted 17 of 24 fourth-down chances this season, a league-high 70-percent rate. (This shouldn’t exactly come as a surprise. In the summer, the team hired a quantitative analyst, 2017 Skidmore College graduate Derrick Yam, after he wrote a paper of the benefits of going for it on fourth down.) That means more time on offense with a chance to score points, and more “truss” in the locker room.

Given the paranoid nature of pro football coaching staffs who don’t want to give away any trade secrets, Stern isn’t being made available for interviews now to talk more about his job, or how he’s ascended the Ravens coaches’ pecking order. But the kid who for 13 years attended the tiny kindergarten-through-12th grade Park School—just a short drive from the Ravens practice facility in Owings Mills—did speak enough about the nitty-gritty, calculus-style of his work responsibilities for an article earlier this year by Sheil Kapadia of the subscription sports website, The Athletic.

The story essentially blew Stern’s cover. Here’s an excerpt:

The Ravens, like other teams, have built their own analytical model for fourth-down decision-making that accounts for a number of factors—factors that they prefer not to share publicly. There are two numbers to weigh with every decision. One is win probability—a percentage that reflects the team’s chances of winning based on the various options at any given time in the game. The other number is a break-even success probability. The model comes up with an estimate of how likely the team is to convert the fourth down. Part of the decision then comes down to how high that number has to be to justify going for it.

“It might be that there’s a decision that because we’re up by 14 points already, the decision that we make doesn’t change our win probability very much because we’re really likely to win the game no matter what,” explains Stern. “But in that moment we know that we would only need like a 15-percent chance of getting it to justify going for it. It doesn’t change our win probability that much in the game. It’s just the risk/reward calculus. So there’s situations like that, too.

“Or maybe there’s one where the win probability is really big, but it’s only because it’s a tight decision in a critical moment in the game. Like late fourth quarter, we could have a really tight decision where on average we’re gonna get it 55-percent of the time, we think, and to justify going for it we need to get it at least 50-percent of the time. So that’s a really tight difference. We would need to be very confident in our estimate of how likely we are to get it in order for that decision to be the correct decision. So it’s a really tight decision compared to one where the break-even is 20 percent and the probability of getting it is 50 percent”

Like we said, whiz kid. Here’s a little more:

What makes it easier, according to Stern, is that Harbaugh is familiar with concepts like win probability and expected points added (EPA). He wants to know the actual numbers in his headset during the game as he’s making decisions.

“We talk about all the different scenarios, and he basically gives me a percentage,” says Harbaugh. “So what’s the added win percentage of going for it? He’ll give it to me like one, two, three, four, five, six, up to whatever. Then you just decide if you want to do it. It’s not strictly based (on the numbers). I listen to it. If he starts telling me 3 and 4 percent, I get really interested. If it’s 1 or 2 percent, I’m still interested—especially if it’s short, if I think we can get it.”

Says Stern, “I just remind him during the game that this is what we were planning to do. If something’s changed, then he’ll argue back. You’ve just gotta be ready for him to push back, like, ‘You really think we should?’ Or ‘I don’t want to do that.’ I don’t take offense to that during a game at all. He’s the head coach so he’s gonna make the decision that he thinks is best.”

None of this shocks those that have known Stern since he was a kid. According to one Baltimore magazine staffer whose child was friends with Stern, he used to send his own text messages to set up playdates—in second grade—and once administered an I.Q. test to the child during one of them.

Asdourian, who, more recently, taught Stern calculus and is Park School’s math department co-chair, says, “He’s really just an extraordinary person. It’s impressive to see his mind at work. In class, he could pick up the subtleties of the chain rule or the fundamental theorem of calculus very quickly. In mock trial, he had this amazing ability to summarize everything that has happened in the case and give us a five-minute summary that would end up often being highly persuasive to the judges. He was always incredibly verbally facile and intelligent, and had wonderful instincts.”

The kid in Harbaugh’s headset graduated magna cum laude (with distinction for us lay people) from Yale, where in addition to co-captaining the university’s mock trial team to the top spot in the country, he worked as a student assistant for the Yale football team, as a sports broadcaster and producer for the school’s athletics department, and wrote for the student newspaper.

“He’s one of those people who talks about something like it’s pie-in-the-sky, but at the same time, it isn’t,” Asdourian says. “He would say, ‘I think one day I’d really like to work for a football team, like the Ravens.’ Some kids would say that and you’d go, ‘Well, I hope that works out.’ And when he would say it, he was intense enough and smart enough that you sort of go, ‘Huh, I wonder if he’ll actually pull that off?’”

We now have the verdict.