Sports

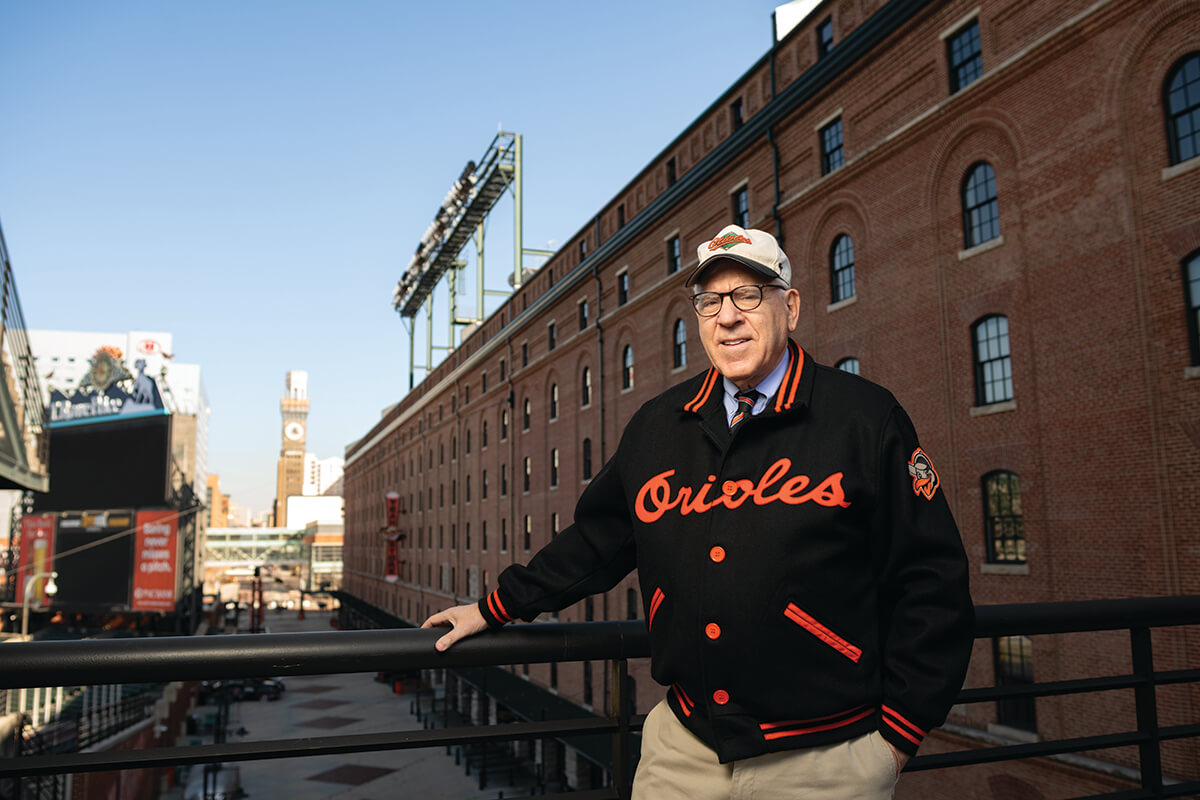

Will David Rubenstein’s Deep Pockets Help the O’s Finally Win Another World Series?

The club's personable new owner—who rode the city bus to catch O's games at Memorial Stadium as a kid—has increased the team's payroll up to more than $150 million.

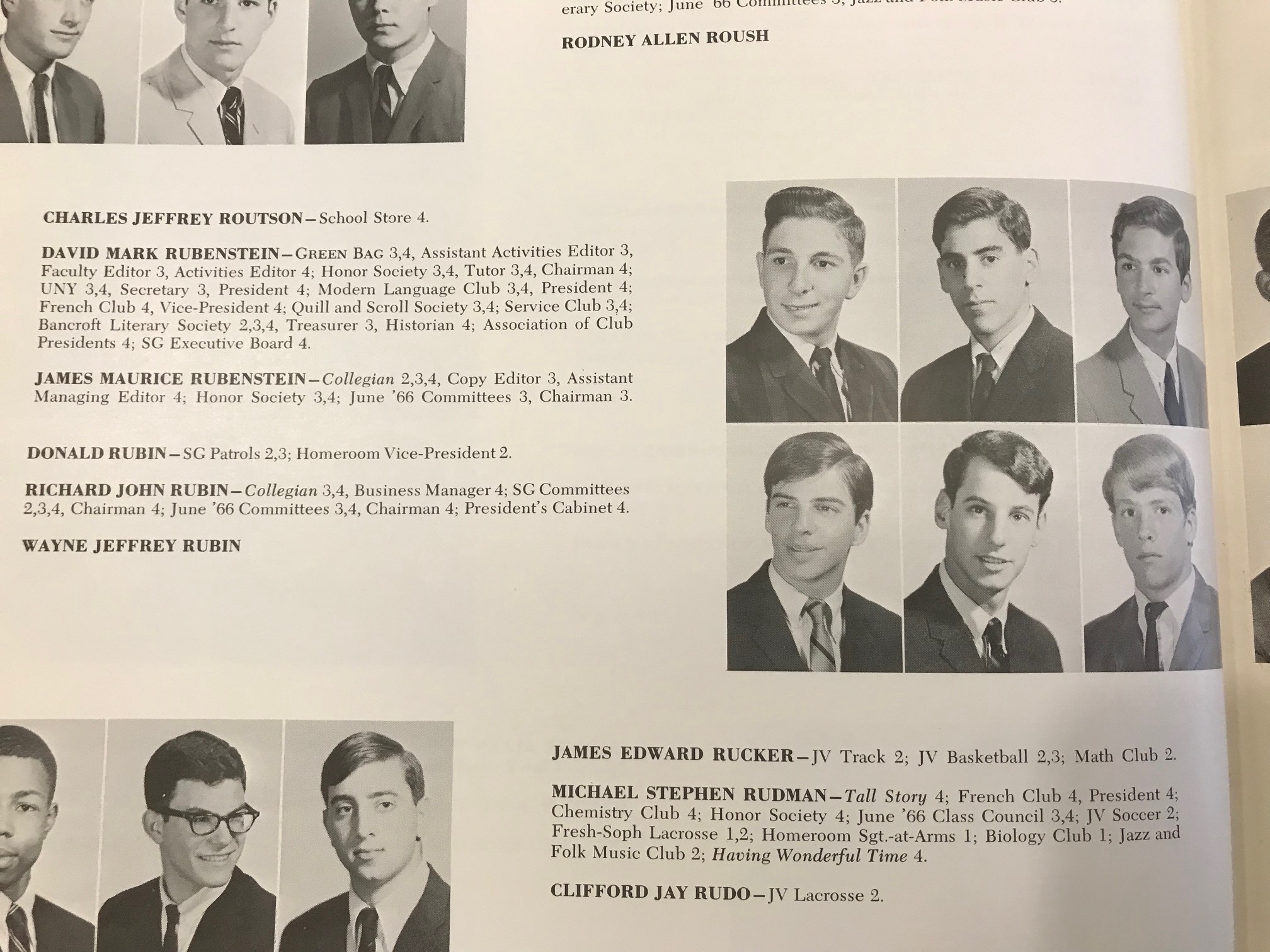

If you happened to catch a teenage David Rubenstein during an Orioles game at Memorial Stadium in the 1960s, you might have noticed that he wasn’t always paying attention to the action on the field. Instead, his head might have been buried in a biography of John F. Kennedy or the pages of some other history text.

“I usually took my books,” he says, “and read so much that my friends would make fun of me.”

Rubenstein’s voracious reading was perhaps a sign that he’d one day work in the White House and later pen a book about U.S. presidents, but it was hardly an indication he would one day become a billionaire or the team’s owner some 60 years later.

But make no mistake, he was also a huge fan. He was the type of kid who snuck down from the 75-cent bleacher seats to the mezzanine, then to the newly created box seats as the innings wore on to get a better view of his baseball idols. Among his favorite O’s were some of the modern franchise’s early folk heroes: 6-foot-3, 215-pound catcher Gus Triandos (“slow runner, but hit a lot of home runs,” Rubenstein recalls); 1960 American League Rookie of the Year Ron Hansen; and All-Star first baseman Jim Gentile.

Then came along a young Brooks Robinson (“a modest, unassuming, low-key guy; I really admired him”), followed by an even younger Jim Palmer, who at age 20 was just a few years older than Rubenstein when he left town for college in 1966, the year the O’s won their first World Series.

Sometimes, an usher working the box seats tapped Rubenstein or one of his buddies on the shoulder and told them to leave. They’d scram, then come back. “We were just kids having a good time,” says Steve Baron, a longtime friend of Rubenstein’s. They rode the city bus to the stadium from their middle-class, predominantly Jewish neighborhood of Fallstaff in northwest Baltimore. In the fall, they split $2 student season tickets to watch the Colts play football, too.

In the pages of his books, Rubenstein was exploring a broader world, but at those games, he mostly just had fun. Making his way to the box seats where O’s then-owner Jerry Hoffberger sat was not part of some master plan.

“I didn’t know what ownership was,” Rubenstein says, chuckling.

On Opening Day late last March, five days after longtime Orioles owner and Greektown-raised lawyer Peter Angelos passed, another local kid who made good—one even richer than Angelos and more of a prodigal son—held his first press conference at Camden Yards.

Sporting a white O’s home jersey, an enthusiastic grin, and a seemingly limitless bankroll, Rubenstein announced, “This is a new day, a new chapter,” from the sixth floor of the B&O Warehouse. And O’s fans, who had soured on the previous regime’s recent underfunded payroll and a 40-plus-year championship drought, were eager for the chapter to begin.

It’s early January and Rubenstein, 75, bespectacled with parted white hair, sits in front of a computer in an office at his suburban Bethesda home. He’s dressed in a suit and tie, typical for his many public appearances. As tycoons go—especially one who got rich in private equity—Rubenstein is astonishingly well-liked, largely due to his easy manner, disarming sense of humor, and fluency in a variety of subjects, including business, politics, history, and, increasingly, sports.

A mural of the U.S. Capitol Building in Washington, D.C.—where he made his career and fortune—is behind him. At 27, Rubenstein achieved his dream of working in the White House, as President Jimmy Carter’s deputy domestic policy advisor. Ten years later, he co-founded the private-equity firm Carlyle Group, which made him extraordinarily wealthy (Forbes estimates his net worth around $4 billion).

Over the last few decades, he’s given away more than $700 million and become known for “patriotic philanthropy,” like buying and then loaning a rare copy of the Magna Carta to the National Archives and putting up at least $10 million to fix the Washington Monument. Until this February, he was the chair of the board of the Kennedy Center. (Donald Trump removed him from the position and installed himself.)

He’s become a prominent interviewer of public figures, too, hosting TV shows on Bloomberg and PBS. He has written books on investing, politics, and leadership. His latest, The Highest Calling, includes interviews with most living U.S. presidents, including Joe Biden and Trump.

Maybe as impressive as Rubenstein’s connections is the fact that he never uses notes when giving a speech or interviewing someone.

“He has a photographic memory,” says Baltimore’s Carla Hayden, the Librarian of Congress, a friend. “He absorbs and devours information.”

Rubenstein has been focused on baseball a lot more lately. In his first full offseason as Orioles owner since he led the group that bought the team from the Angelos family for $1.7 billion last March, Rubenstein and ownership partner Mike Arougheti have spoken with general manager Mike Elias almost daily about personnel decisions—and Rubenstein is getting up to speed on the modern game.

Gone are the days of his youth when batting average, RBI, and home runs were the only important stats. Today, teams value wonky-sounding metrics like “on-base plus slugging percentage” or “wins above replacement”—an estimate of how many wins a player contributes compared to an average MLB Joe at his position.

“OPS, WAR. I’m learning,” Rubenstein says. But he stresses that he’s not a meddling owner: “I’m [not] saying, ‘Mike, pay this, pay that.’”

Importantly, Rubenstein has put no limit on how much his GM can spend, a luxury for a middle-market team in a salary-cap-less sport where tickets and concessions generate most revenue.

The Orioles’ spending had plummeted in recent years to among the lowest in baseball. Fans were told to trust the process as the team fortified its farm system and spent little in free agency. The rebuild seemed to be working—the club made the playoffs the year before Rubenstein purchased it—but the O’s clearly needed an influx of energy and cash.

In walked Rubenstein. This year, the payroll is up to more than $150 million, 15th of 30 MLB teams, 40-percent higher than early 2024—and more than triple the budget from 2021. (The O’s also made the playoffs in Rubenstein’s first season, although, for the second year in a row, they didn’t record a postseason win.)

This offseason, Elias signed free-agent outfielder Tyler O’Neill to a three-year, $49.5-million contract, the first multiyear deal Elias has given out since becoming GM in November 2018. “We can [now] run the team the way we feel is optimal,” Elias says. “They’ve really liberated us to do our jobs.”

But even with a lot of cash on hand, difficult decisions must sometimes be made. Undoubtedly, the most-discussed topic of this Orioles offseason was the one who got away: O’s ace Corbin Burnes, who signed a six-year, $210-million deal with the Arizona Diamondbacks in December. Fans thought, “uh oh, here we go again,” even though baseball insiders had never expected Burnes to stay here after he arrived in a trade with one year left on his contract.

“Money was not the issue,” Rubenstein insists. Family was. Burnes, 30, and his wife have had a home in Phoenix for six years and are raising three young kids there, including twin girls born last summer. It’s hard to beat driving them to school and going to your home ballpark the same day, Burnes said upon introduction in Arizona.

“I’m not sure any amount of money would have made much difference,” Rubenstein says. “We had an offer that, when you add it all up, was very competitive. We were prepared to put in the money necessary.”

“WE CAN RUN THE TEAM THE WAY WE FEEL IS OPTIMAL.”

Rubenstein didn’t always have the money. His father, Robert, a former Marine who served in World War II and whose family immigrated from Ukraine, worked as a U.S. Postal Service file clerk. His mother, Bettie, went to work making dresses when her only child was six. They lived in a modest, two-bedroom rowhouse at 4834 Beaufort Ave., bought for $6,000, followed by another at 4213 Fallstaff Rd., purchased for $8,000 in 1959.

Like many sports-mad boys, Rubenstein’s childhood dream was to be a pro ballplayer—but he quickly realized he was too small and slow. Later, he was greatly inspired by JFK’s televised inauguration address on Jan. 20, 1961—“Ask not what your country can do for you, ask what you can do for your country.”

The next day, Rubenstein and his classmates analyzed the speech in Mrs. Joan Shaw’s sixth-grade class at Fallstaff Elementary. And when he found out that a lawyer, Ted Sorensen, had written it, Rubenstein had a new dream.

“I was reasonably good at writing and reading and talking,” he says. “That’s why I ultimately went to law school. I thought being a policy advisor in the White House would be the highest calling of mankind.”

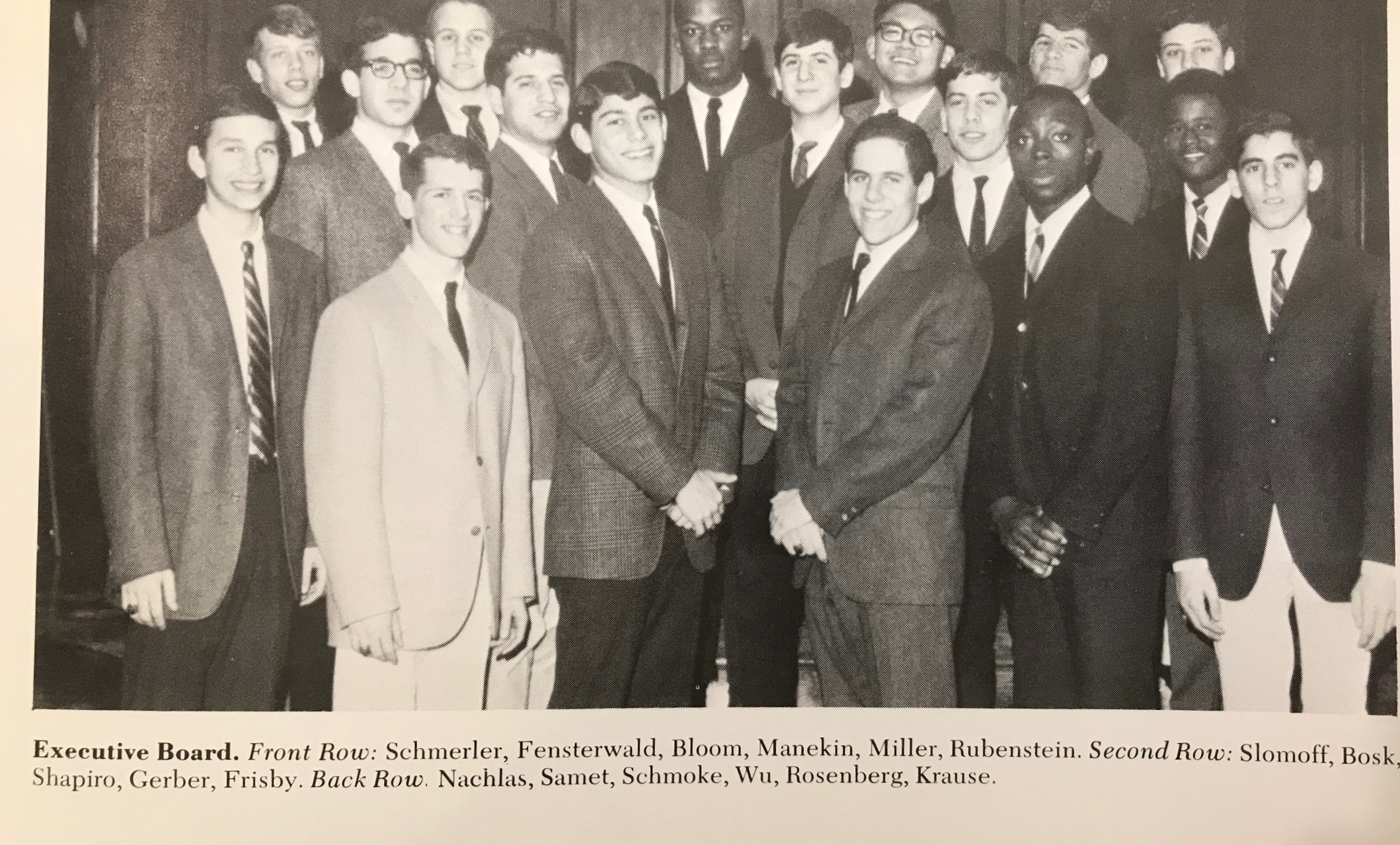

Rubenstein bussed to high school at City College, about a 75-minute ride each way, and joined clubs to strengthen his college applications. He went to Duke University and law school in Chicago on scholarship. After graduation, he got a job with a New York firm where his idol, Sorensen, worked. And then one day he got a fateful call about working on the presidential campaign of a peanut farmer from Georgia. He said yes.

In the years to come, Rubenstein was a regular in the Oval Office and flew on Air Force One. But then Jimmy Carter lost his 1980 re–election bid and Rubenstein faced a new reality: as a political has-been. He became a partner in a D.C. law firm, but didn’t enjoy it and saw friends making more money in business.

In 1987, newly married and raising the first of his three children, he cofounded Carlyle, a leveraged buyout firm that grew out of his and his partners’ Washington relationships. Six years later, the firm held a majority stake in about a dozen companies that generated billions in revenue annually, chiefly from the U.S. government. (A 1993 New Republic cover story by Michael Lewis said Rubenstein “almost unwittingly” helped create a “new social type: the access capitalist.”)

Carlyle eventually went global and has gone on to have more than $400 billion of assets under management. Rubenstein stepped down as co-CEO in 2017.

Over the years, he didn’t completely forget Baltimore. Rubenstein served on the boards of Johns Hopkins University and Hospital. In 2007, he donated $5 million for a building on Wolfe Street that’s part of Johns Hopkins Children’s Center. And he’s reunited with at least half a dozen old friends from the Lancers Boys Club of his youth who’ve gone on to disparate careers.

“For a couple years, he would fly us all up to Nantucket,” says Baron, the former CEO of Baltimore Mental Health Systems, referring to Rubenstein’s private jet and $39-million estate on the exclusive New England island. When they last visited two years ago, the guest book included a familiar name: Joe Biden.

But after Rubenstein returned home for his parents’ funerals at Mikro Kodesh Beth Israel Cemetery in East Baltimore in 2012 and 2017, his perspective changed. He realized he had neglected his hometown, especially after his parents retired to West Palm Beach, Florida, years earlier.

“Baltimore gave me a good public school education. My parents grew up here, my parents were married here, my parents are buried here, and I’m going to be buried here,” he says. “I gave away a fair amount of money, but I didn’t do as much for Baltimore as I thought I should have.”

He took note of the population decline, crime, and relative lack of corporate headquarters. He had long talked privately with friends about doing something big, namely, buying the Orioles, to help “revitalize” the city, he says.

But as far as he knew, the team wasn’t for sale.

Then the details spilled out about an ugly lawsuit filed by Louis Angelos against his brother, John, and his mother, Georgia, revealing that Peter Angelos—who’d bought the Orioles at auction for $173 million in 1993—had been incapacitated since a collapse in 2017.

Roughly three years later, John, the eldest of Peter’s two sons, was appointed the team’s MLB-mandated “control person” by his mother. By 2023, John would say publicly that the team would be “financially underwater” if it signed players to long-term contracts.

Meantime, a new long-term Camden Yards lease agreement between the state and the Orioles was overdue. Deep-rooted fears about the team leaving the city (aka The Colts, v2.0) grew. In 2022, Ted Leonsis, the D.C.-based owner of the Capitals, the Wizards, and a burgeoning sports streaming channel, Monumental, proposed Rubenstein invest in his two teams, media platform, plus the Orioles, if Leonsis could reach a deal to buy the team. He negotiated unsuccessfully, but the wheels were greased.

In July 2023, John Angelos asked to meet Rubenstein for lunch in Nantucket, where Angelos was renting a home. He offered a minority share. Rubenstein was intrigued but wanted more: a “path to control” in a few years.

A few weeks later, he heard better news. Angelos was willing to sell complete control.

Georgia Angelos endorsed the idea. She liked that Rubenstein was from Baltimore and she “had seen my TV shows, read my books, and thought I might be a good owner,” he said in a 2024 podcast.

Negotiations began and continued for months, through Christmastime 2023, when lawyers and bankers joined a massive Zoom call between interested parties—and everything nearly fell apart. Rubenstein bristled at comments from Angelos’ reps he considered “somewhat insulting about our knowledge of finance” regarding an item on the team’s balance sheet.

“I don’t want to put up with this anymore,” he said on the call in frustration. “I’m done.”

He logged out, walked away, and left everyone wondering what to do. “I thought they would sell to somebody else,” Rubenstein says now, but a week later, cooler heads prevailed, talks renewed, and the deal was finalized.

Since taking over, few dispute that Rubenstein has hit almost all the right notes. Last Opening Day, he proclaimed his goal of returning a World Series winner to Baltimore for the first time since 1983. Excitement filtered to the clubhouse.

“We want leadership to want the World Series as much as we do,” Gunnar Henderson said to reporters.

On Eutaw Street, Rubenstein chatted with fans and famed beer vendor Fancy Clancy and took selfies with anyone who asked. Across the street at Pickles Pub, Rubenstein’s ownership partners, led by Arougheti, bought everyone a pre-game beer. Rubenstein has since attended dozens of games and has deliberately spoken directly to Baltimoreans.

“I want to give people a sense that there’s real hope in Baltimore,” he said in a speech at Beth Tfiloh Congregation in November. “The Orioles are the heart and soul of the city in many ways. When they do well, it makes the whole community feel much better about itself.”

He now has his own box—Suite 33—and he’s invited season-ticket owners to share it with him, perhaps remembering the thrill he felt as a kid at Memorial Stadium. But he finds that he prefers his front-row seat near the home dugout, on top of which he once awkwardly danced to “Thank God I’m a Country Boy.” He was Mr. (Ruben)Splash another evening, hosing fans in Section 86. He has tossed vintage O’s hats—the style he wears—into the seats and made funny promotional videos.

“He loves it,” says longtime friend, former Baltimore Mayor and current University of Baltimore president Kurt Schmoke, who’s part of the new ownership group. “He enjoys getting out into the crowd, walking around, taking pictures.”

“THE ORIOLES ARE THE HEART AND SOUL OF THE CITY IN MANY WAYS.”

People seem to enjoy seeing him, but goodwill only goes so far. Fans remember the Angelos era, which started with a similar narrative about a locally invested, wealthy owner. Even if this offseason underwhelmed some—on top of losing Burnes, no truly marquee player was signed—the payroll increase signals a will to win.

The O’s have revamped their business operations, hiring Catie Griggs from the Seattle Mariners last July to oversee things. The club has $400 million in state funding to refurbish Camden Yards, part of a new 15-year lease agree- ment that began in 2023. The O’s can unlock $200 million more from the state and add another 15 years to the deal if it agrees on a ground lease to redevelop the real estate around the ballpark, which Rubenstein has said he intends to do. Meantime, a 12-item value menu for fans—including $5 beers—revealed in January was a popular choice.

The primary question, though, is whether the O’s will agree to long-term contracts with young stars such as Henderson and Adley Rutschman. If not, what’s the point of anything, really?

“Those are complicated things,” Rubenstein says. “I would just say the Orioles have a tradition of having some players stay with the team for a long, long time,” referring to two of his boyhood heroes, Palmer and Robinson, as well as Cal Ripken Jr. “And I hope Gunnar Henderson and Adley Rutschman will be in that tradition.”

Rubenstein knows the optics and reality: They are a new generation’s baseball idols. In October, on the first day of the O’s short-lived 2024 postseason, Rubenstein headlined a networking event hosted by nonprofit media outlet The Baltimore Banner at Meyerhoff Symphony Hall.

“How many people think we should keep more of our young players in Baltimore?” he asked the audience. A roar of applause followed.

Months later, on the eve of the 2025 season, he shares this answer: “I’d like fans to know I’m focused on trying to win a World Series. It’s not easy. There are 30 teams, and only one can win, but we have a good young team, and we’re prepared to spend the money to get a good team and make it even better.”

This year we celebrate our 50th Best of Baltimore issue—our biggest and boldest yet. Subscribe before 6/20 to guarantee your copy commemorating this milestone anniversary.