At 1:04 a.m., as Tuesday night bled into Wednesday morning in Cleveland, the Orioles’ 26-year-old rookie pitcher John Means thumbed five short words and attached a family photo to a tweet that put the previous few days into picture-perfect perspective.

We’re not in Kansas anymore. pic.twitter.com/z3mX4JcTlR — John Means (@JMeans25) July 10, 2019

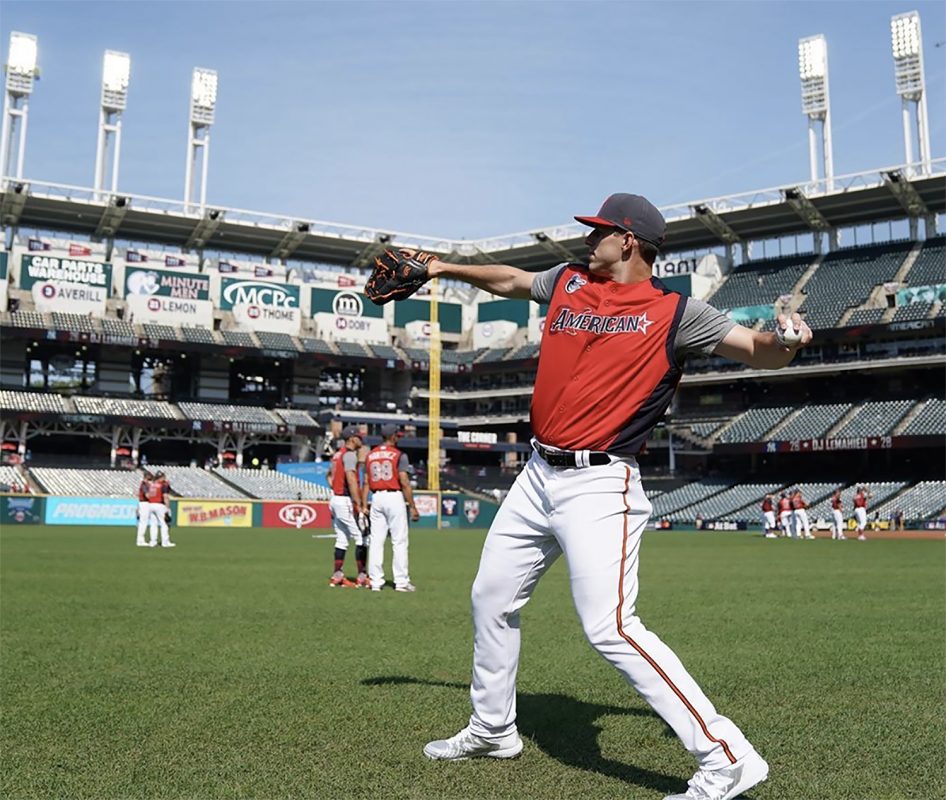

There he was, dressed in a red, white, and blue American League uniform, alongside his fiancée, parents, and younger brother, standing on the field before the Major League Baseball All-Star Game—the unlikeliest of places for a guy with his story.

Means started his baseball career in the Kansas flatlands as a puny 5-foot-4 high school freshman on the “D” team, two levels below junior varsity, his father, Alan, told the Sun. Four years and a footlong growth spurt later, Means was originally drafted by the Atlanta Braves in the 46th round, so deep in the process that the round doesn’t exist now.

He’s a guy who, three offseasons ago, tried his hand at substitute teaching to help pay the rent. He grinded in the unglamorous minor leagues for so long, that he almost gave up baseball altogether. Last year, while with the Bowie Baysox for the third season and making $3,000 a month, he updated his LinkedIn profile for a real job search. His skills: critical thinking, problem solving, a drive for success.

So, although Means didn’t even end up taking the mound in the All-Star Game on Tuesday night—the pinnacle of professional baseball when it comes to individual honors—you can probably imagine why he was still happy to just be invited. “I don’t think disappointed is the word,” he said after the game. “[I was] just living it out and trying to soak it all in.”

It was, after all, a surprise, as recently as 10 days ago when Means sat across from Orioles manager Brandon Hyde in his office at Camden Yards and Hyde told him he was picked as an All-Star reserve as a pitcher. “You’re joking,” Means said, generally the quiet, unassuming type. “This isn’t that funny.”

The O’s of course were pushing fans to vote for Trey Mancini into the nationally-televised summer classic, but he fell short of the results needed for a starting spot. With plenty of outfield and first baseman depth on the American League roster—and a requirement to put at least one person from every team on an All-Star Game roster—Means was chosen as the O’s representative based on peer balloting and the discretion of MLB decision-makers.

Frankly, having a relatively unknown all-star was the appropriate choice for a team in such a state of extreme rebuild like the Orioles, one with the worst record in baseball. But Means was also deserving.

Of pitchers who have thrown at least 80 innings this year, his 2.50 earned-run average—a longstanding key metric grading pitchers’ performance—ranks second in the American League. He began the year as a reliever before becoming a starter in April and has a 7-4 record.

Now, he and his path to semi-stardom is known. (On Monday night, he’ll be at the Guinness Brewery in Halethorpe for a fan meet-and-greet and drink.)

Without any college offers out of high school, Means matriculated to Fort Scott Community College in Kansas, on the recommendation of the Braves scout who helped draft him. Then, he pitched for the Mohawk Valley Diamond Dawgs in a summer league in New York in 2012, where he impressed with a 6-foot-3 frame and effective change-up. By chance, he got an offer to play for West Virginia University. A coach saw Means while he was evaluating another player the school had signed.

The Orioles picked Means again the draft in the 11th round (331st overall) in 2014. Looking back, it was a slow and steady rise from there. He played for the Delmarva Shorebirds, the Frederick Keys, and the Baysox. He was promoted to the Norfolk Tides last year and was the last minor-leaguer called up to the O’s, making just one appearance.

This is where the Orioles new analytics-driven management team comes into play with helping write this success story. This offseason, Means decided to adjust his own approach to fit the new leadership. He spent parts of the offseason training in St. Louis, working on biomechanics, and getting the most out of his body at P3 Premier Pitching and Performance. Means has never been a power pitcher. But after the offseason work, his fastball increased to 94 miles per hour from the high 80s, and he slowed down his change-up to keep hitters off-balance.

No. 67 arrived at spring training with nary an outside expectation, but his improvement was noticeable, and he made the O’s roster as one of the last players selected. In a season that was relatively a clean slate, where anyone in the organization would have the opportunity to prove themselves, Means took advantage, and set the stage for the position he put himself in this week in Cleveland.

There, he took questions on media day at the hotel, sitting in front of placard with his name on it. He soaked in the Home Run Derby as a field-level spectator on Monday night, and the next day shared the locker room and bullpen with more established players with a multi-million dollar net worth, who he joked would have no idea who he was.

Maybe this was the most lasting impression: On his way to the All-Star Game red carpet pre-game festivities, he sat with his fiancée, Caroline, a former pro soccer player, in the bed of a white Chevy Silverado pickup truck. They rolled down the street outside Progressive Field, and waved to onlookers as if they were in a high school parade.

It may have felt a little bit like Kansas, but Means’ was right. He wasn’t there anymore.