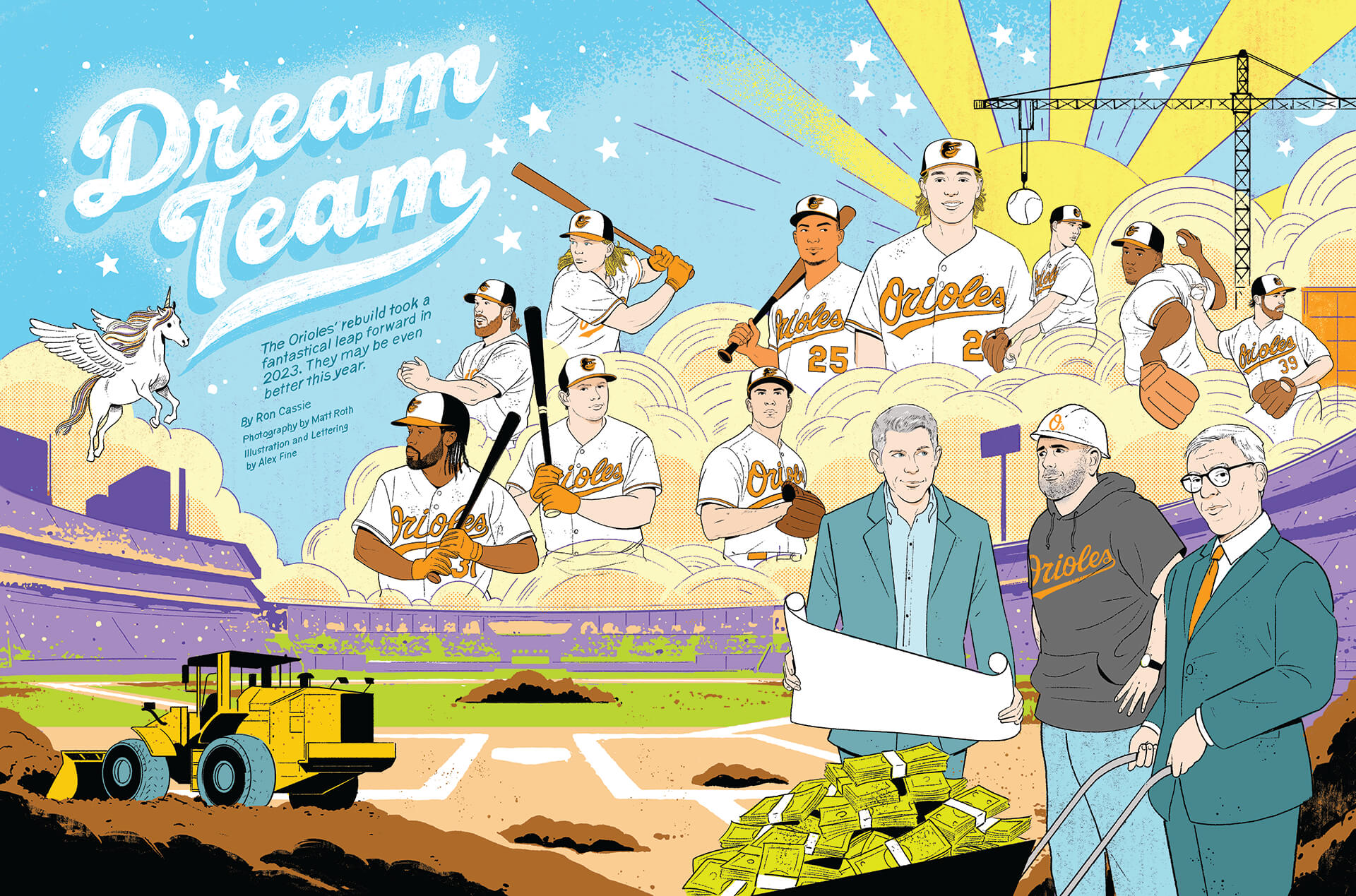

Dream Team

The Orioles' rebuild took a fantastical leap forward in 2023. They may be even better this year.

By Ron Cassie

Photography by Matt Roth

Illustration and Lettering by Alex Fine

n the subdued O’s locker room following their playoff sweep at the hands of the Texas Rangers last October, local reporters quickly moved on from the Game 3 thrashing that had just concluded. The beyond-all-expectations season may have come to a disappointing and screeching halt, but the Orioles’ stunning 101 wins and the AL East title run had become the talk of baseball. Left fielder Austin Hays, who had suffered through three 108-plus losing seasons and four last-place finishes with the organization, was asked when he knew the Birds had taken flight.

“For me, it was mid-June,” said Hays, who made his first All-Star appearance in July and allowed himself a little smile in reflection. “Any team can have a good month. Some put together two. We’d done that and then won a bunch in a row [five straight from June 8-13, pushing their record 18 games over .500]. We were three months in and still playing winning baseball. I thought, ‘This is just who we are now—a good baseball team.’”

In an interview at Camden Yards for this story shortly before he departed for Sarasota and spring training, general manager Mike Elias was posed the same question, but he had a different answer. In the eyes of the prematurely white-haired, 41-year-old GM, who had been through all this before, the club had found its wings almost a full year earlier—during its 10-game winning streak in early July 2022. It was the sixth-longest such streak of the MLB season. Every major-league club that had won eight or more in a row that year, seven in all, reached the playoffs except the upstart O’s, who fell just short. “It signaled this [the suffering of the past four seasons] was over,” Elias said. “Obviously, we missed the playoffs at the end, but bad organizations don’t win 10 straight.”

Austin Hays after striking out in Game 3 of the AL Division Series against the Rangers last October in Texas. —AP Images

The chronically scuffling Orioles were 33-44 at the start of that streak, which began six weeks after Rookie of the Year runner-up Adley Rutschman’s highly anticipated callup from AAA Norfolk. They won five one-run games and rallied three times in the bottom of the ninth during the 10-game stretch, displaying an unmistakable grit and comeback ability that would become a trademark. Since then, the O’s have spent a total of three days with a losing record.

Elias, who is relaxed and easy to talk with one-on-one, recalled a similar experience with his prior employer, the Houston Astros, where he served as assistant general manager and oversaw the scouting department. That team bled through three 106-plus losing seasons before improving—it was a low bar—to 70-92 in 2014. But, in 2015, just like the O’s in 2022, the Astros seemingly came from nowhere and spent the year knocking on the door of their first playoff appearance in nearly a decade. On the final day of that season, the Astros needed to win—or for the Angels to lose—to make the postseason.

“We took it into the last weekend of the season, and I went on the road trip with the team to Arizona,” recalled Elias, who was named baseball’s Executive of the Year last season. “We were playing the Diamondbacks, and Jeff Luhnow [Houston’s then-GM] and I were sitting in Chase Field, following the games on my phone. We didn’t win, but the other team [the Angels] lost, too, which clinched it. Even after the loss, we celebrated in the clubhouse. It was such a big moment because it had been a brutal rebuild. Then, the team kind of popped organically.” Sound familiar?

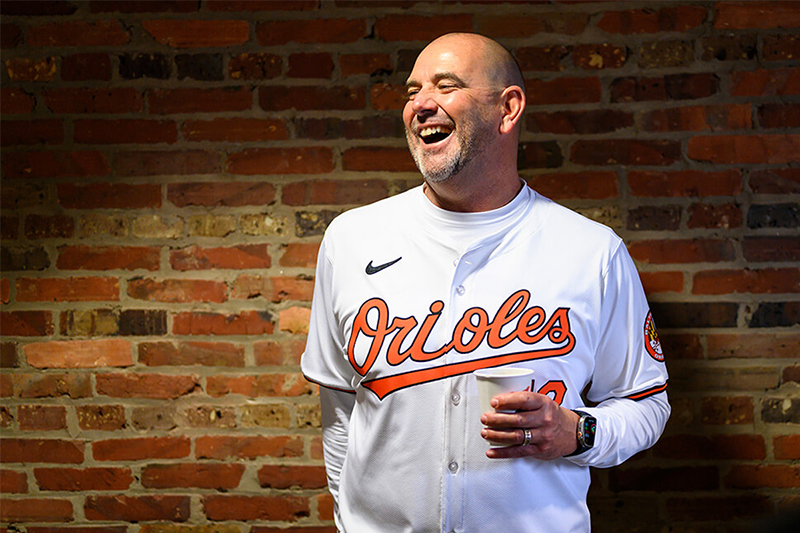

Mike Elias on the field at Camden Yards in February.—Photography by Matt Roth

he hope in Baltimore is that the similarities between the O’s and Astros won’t end there. In 2017, Houston won their first-ever World Series (okay, abetted with the help of sign stealing) on their way to building a dynasty. They’ve captured six AL West titles over the past seven years and added a second World Series championship in 2022.

And why not? (To borrow a phrase from another era.) The Orioles’ two-year transformation from 2021, when they lost 110 games and finished 48 games out of first place, to 83 wins in 2022 and 101 wins in 2023, is unprecedented. The Birds’ 31 additional wins from 2021 to 2022 is the third-best ever in the divisional era. But of the 14 teams that added at least 27 victories year-over-year since 1969—the start of divisional play—only one, the 1992 Atlanta Braves, improved their record the following season, and that was by four games. Not close to the Orioles’ subsequent 18-win jump. For the Braves, it marked the beginning of a 15-season run that included 14 playoff appearances and the 1995 World Series title.

It is not likely the O’s will repeat 101 wins this season, however. On average, since the Boston Beaneaters went 102-48 in 1882, only one team a year breaks the 100-win threshold (although more have accomplished the feat in recent seasons.) There’s also a good chance the Birds will not win the deep-pocketed, talent-rich AL East again, either. Overall, the O’s, Rays, Jays, Yankees, and Red Sox combined for the third-best division record ever last season, despite down years from the Yanks and Sox. But 100 wins is just for bragging rights. More importantly, the 2024 Orioles look better equipped to win a playoff series or two, which are all about pitching matchups. In the end, that’s what matters most.

Just days before the start of spring training, Elias pulled off the trade Birdland had been waiting for the entire off-season. He dealt two prospects—Joey Ortiz, a promising infielder with little chance of cracking the starting lineup, and the talented, if injury-prone, lefty D.L. Hall—to Milwaukee for top starter Cobin Burnes.

Gunnar Henderson celebrates a three-run home run during a game in Boston last September.—AP Images

Send Burnes, the NL’s 2021 Cy Young winner, 2022 strikeout champ, and 2023 WHIP (walks plus hits plus innings pitched) leader, to the hill for Game 1 and you’ve got the opposition on its heels from the get-go. Follow Burnes with a healthy Kyle Bradish, third among AL starters in ERA last year, a healthy John Means, who pitched well at the end of last season after returning from elbow surgery, and the young, flame-throwing Grayson Rodriguez, and suddenly the O’s playoff rotation looks tough—not merely capable. Even without Bradish or Means, the starting rotation, which has some depth, figures to be improved.

“The Burnes trade was rightfully noteworthy,” said Elias, who’s entering his sixth season as GM, of the national buzz and ecstatic local social-media reaction around the move. “This is not something we’d done yet [trading prospects for a major acquisition]. It is definitely a statement from us that we are super-focused and prioritizing this current team and their 2024 season above almost anything else.”

Of course, the Orioles do not just have a metaphorical new lease on life, but a literal one at Camden Yards for the next 30 years—and a new billionaire owner. It’s a sudden change of fortune that has O’s fans delirious over the promise of the next few seasons. The son of a Baltimore postal worker, 74-year-old David Rubenstein is a co-founder of one of the largest private equity investment companies in the world. It is broadly assumed that he’ll be more willing than the Angelos family to take on a large contract at the trade deadline, for example. Or, and this is the real hope, sign the O’s budding young superstars to contract extensions before they become eligible for free agency. Meanwhile, the team’s projected starting second baseman, 20-year-old Jackson Holliday, is the pre-season odds-on favorite to win this year’s AL Rookie of the Year award. That’s on the heels of now-22- year-old shortstop Gunnar Henderson, who won it last year.

Did we mention that after all the big-name call-ups, a recent MLB poll of executives still voted the Orioles’ farm system the best in baseball by a whopping 75-percent margin?

Kyle Bradish douses Grayson Rodriguez and Gunnar Henderson, after a September 2023 game against Tampa Bay.—AP Images

he Orioles’ ownership, specifically the late owner Peter Angelos’ two sons, John Angelos and Louis Angelos, lured the then-35-year-old Elias away from the Astros in the fall of 2018. They offered control of baseball operations and, apparently, a lot of money, to the former Yale pitcher. Although the terms of his and manager Brandon Hyde’s contracts have never been disclosed—Elias keeps his cards exceedingly close to his vest—it was reported by USA Today baseball writer Bob Nightengale, who broke news of the hire, that the O’s had made Elias the highest-paid first-year GM ever.

It didn’t hurt that he’d grown up in Northern Virginia and saw Cal Ripken Jr. play at Camden Yards as a kid. His sister and parents still live in Northern Virginia, and his wife Alexandra’s parents live in Naples, Florida, not too far from spring training, which makes everything a good fit for the couple and their two children.

In 2018, the final year of the Dan Duquette-Buck Showalter era had ended in total collapse and a franchise-record 115 losses. Most of the O’s nucleus—Manny Machado, Zach Britton, Jonathan Schoop, Kevin Gausman, Darren O’Day, and Brad Brach—had been traded away at midseason. It was akin to running a white flag up the foul pole. Team leader and former All-Star Adam Jones was granted free agency after the season. Showalter, who had managed the O’s to three post-season appearances, was dismissed.

And no immediate help was on the way. The top three farm clubs, the Norfolk Tides, Bowie Bay Sox, and Frederick Keys, all posted losing records the year prior to Elias’ arrival. There was no scouting and development facility in Latin America. The analytics department was understaffed and under-resourced.

If anything, however, the size and scope of the challenge, not to mention the opportunity to mix it up in the highest-profile division in baseball, appealed to Elias. In the front office world of Major League Baseball, where franchises are owned by corporate titans—the O’s were valued at $1.76 billion when sold—putting a winning team together is every bit as cutthroat a game as the one played on the field. And infinitely more complex. (In recent years, several GMs have been fired or forced to resign after breaking MLB rules, including the Astros’ Jeff Luhnow, following the team’s sign-stealing revelations; the Mets’ Billy Eppler, for repeatedly placing healthy players on the injured list; and the Braves’ John Coppolella, for violations in the international players market. Several years ago, former MLB executive David Samson said that every team in the game is guilty of breaking “tampering” rules regarding others teams’ players and staff.)

Mike Elias addresses the media at Camden Yards during the Orioles' annual winter Birdland Caravan. —Photography by Matt Roth

“When you’re playing and you transition into a profession that’s just as competitive as playing, that competitiveness stays with you,” said Elias, who admits to “doing the bare minimum in the classroom” at Yale while being very focused on baseball. “[The desire to get better] eats at you all the time. I don’t ever relax. I’m always worried if I’m falling behind. I’m always checking my phone. I mean, I enjoy it, too. It keeps your juices flowing as a human being on planet Earth to have something that you’re competing for.”

To put it another way, studying history in college never stoked his curiosity and drive the way putting together a professional baseball club has.

The O’s cupboard was not completely bare, however, when Elias arrived. Hays, center fielder Cedric Mullins, right fielder Anthony Santander, and first baseman Ryan Mountcastle were at various stages of development. Ultimately, as Orioles fans know, that group provided a stable foundation as the Elias-era draft picks climbed the minor-league ladder. The “old guys” are all still under 30.

As is sometimes the case in professional sports, the franchise’s most valuable asset came as a result of their 2018 futility—the subsequent No. 1 pick in the amateur draft. Closely followed, it would turn out, by their second pick at the No. 41 spot. Baltimore sports fans will recall that the Ravens selected a pair of future Hall of Famers, Jonathan Ogden and Ray Lewis, with the then-new franchise’s very first selections in 1996, setting the team on course for a generation. A little more than six months after taking the helm, Elias selected Rutschman and Henderson, who may be viewed in a similar vein by fans down the road.

The consensus top college player in the 2019 draft, the switch-hitting Rutschman instantly became the face of the future. But if Rutschman was a no-brainer, Henderson’s pick proved an early display of several Elias qualities—talent evaluation, the aforementioned penchant for keeping his cards close to his vest, and a willingness to bet big when the right opportunity arises. Not a guy you want to sit down with at a poker table.

With Henderson, the question was less about his potential than concerns the high-school senior would fulfill his commitment to play at Auburn University if he slipped from the first round. The O’s and Elias offered $500,000 “over-slot”—meaning above the MLB assigned value of the No. 41 pick—and put a $2.3-million deal on the table. “We were teed up and prepared to take him,” Elias said. “We did a good recruiting pitch with him and his family to sign him because it was lower than he thought he was going to go, and he could have gone to Auburn. It seems like the baseball gods were smiling on us when Gunnar Henderson fell [into the second round].”

More than mere luck, the signing of Henderson was part of a “portfolio” approach to the draft that Elias had successfully used in Houston. As described by Eric Longenhagen and Kiley McDaniel in their 2020 book, Future Value: The Battle for Baseball’s Soul and How Teams Will Find the Next Superstar, the concept is to save as much of the team’s MLB-allotted draft money as possible with their top selection—while limiting the drop-off in ability—and then use the savings to make an over-slot pick with a talented high-school player who has slipped a notch, possibly because they’re expected to use college baseball as leverage.

The next year, the O’s drafted three key players: infielder Jordan Westburg, who put together a solid rookie big-league year in 2023; No. 2 overall pick Heston Kjerstad, a slugging outfielder; and power-hitting third baseman/left fielder Coby Mayo. In 2021, the O’s selected outfielder Colton Cowser, who, coincidentally, blasted a walk-off home run in the spring training opener this year. Cowser, Mayo, and Kjerstad currently rank as the No. 19, 30, and 31 best prospects in baseball, respectively. Considered a couple years away, 19-year-old first baseman/catcher Samuel Basallo sits at No. 17—the other three are vying for roster spots this year.

One more example of out-of-the-box thinking: Elias’ controversial decision to raise the left field wall at Camden Yards and move it back 26 feet. Overnight, the ballpark went from the first- or second-most homer-friendly in baseball to one that favored pitching, providing several immediate benefits. First, it helped the O’s young pitching staff. Secondly, it made it easier to attract quality free-agent pitchers, such as Kyle Gibson last year, who led the O’s in wins. The team had also drafted a lot of left-handed bats as well, which worked out nicely, maximizing the impact of the shorter right-field porch. Finally, the team is going to be homegrown for the most part and will have young, athletic guys to cover the additional outfield space.

“It’s coincided with winning,” Elias acknowledged. “Has it caused it? It hasn’t hurt, and it seems like we’ve been able to put a pitching staff together more easily the last couple of years. The wall is a part of that. It sort of works for us from every angle.”

It’s all led to the general feeling among baseball experts that the O’s are only getting started.

“Feel free to file this away or print it out and bury it in a time capsule. We’ll see if we are correct 30 years from now,” Baseball America editor-in-chief J.J. Cooper wrote earlier this year, shortly after the Burnes acquisition. “But there are few times in the 20-plus years I’ve been involved in Baseball America’s organizational talent rankings where we’ve had a team that was so clearly viewed as the best farm system in baseball.”

From left, Mike Elias (not facing the camera), third-base coach Tony Mansolino, Brandon Hyde, Ryan Mountcastle, and Grayson Rodriguez

at an off-season community event. —Photography by Matt Roth

wo days after the Angelos brothers made it official that Elias was the O’s new GM, the team announced it had hired analytics guru Sig Mejdal, Elias’ colleague in Houston and, prior to that, St. Louis.

For all intents and purposes, hiring Elias meant the Orioles were not getting one of the best minds in baseball to overhaul the franchise, but two.

If you’ve seen the movie Moneyball or read the 2003 book it was based on—as Elias and Mejadal did—you know it’s about rethinking baseball’s conventional wisdom and relying on analytics to build a team. Think of Elias, the ex-college pitcher, as former ballplayer and A’s GM Billy Beane and Mejdal as young A’s assistant general manager Paul DePodesta, who studied economics at Harvard. Except that Mejdal, who worked as a NASA biomathematician before Moneyball inspired him to pursue a career in baseball, is two decades older than Elias.

“I think we were attracted to each other when I first met Mike,” says Mejdal, who, like Elias, has an easygoing, affable demeanor. At the time, Mejdal was the St. Louis analytics guy and Elias was a scout the Cardinals had just hired out of college. “He was coming into a draft when we were still grappling with the processes. How do we combine this newly available data—when previously all you had was information from the scouts? You could tell Mike was fascinated with this stuff. He was in it with both feet. If a potential draftee looked like a stereotypical ballplayer, fine. If not, so be it. What mattered was the runs they produced.

“It was a time when many scouts were defensive about analytics,” Mejdal continues, “and here was a scout who was trying to figure out how we can maximize production from the draft. That’s what he’s been doing for the 17 years since.”

Chief among Elias’ priorities with the Orioles was building up the analytics and international scouting departments. Every other team had analysts poring over research rooted in pitchers’ spin rates and movement and hitters’ barrel percentage and exit velocity, among the myriad of other new information made available by TrackMan technology, which had been all but ignored under the Duquette regime. (TrackMan devices capture all the data associated with a pitch and swing and pair it with video so that players, coaches, scouts, and front-office executives can access the information whenever needed.)

By the 2020 season, Elias and Mejdal had added 11 staffers to the analytics department.

Two months after his hiring, Elias tapped Koby Perez, who he also knew from his St. Louis days, to oversee the team’s international scouting department, specifically in Latin America. In January, the Orioles officially opened a state-of-the-art, 22.5-acre complex in the Dominican Republic to develop Caribbean, Central American, and South American players.

Following his first season, Elias hired another former Astros colleague, Eve Rosenbaum, to serve as the director of baseball development. Promoted to assistant general manager in 2022, she’s one of highest-ranking female executives in baseball.

A lifelong O’s fan from Bethesda—Rosenbaum was the first girl to participate at Cal Ripken Jr.’s annual summer camp—she played catcher for Harvard’s softball team. Rosenbaum had worked with the Astros since 2015, rising to manager of international scouting in August 2017. She was the third former Astros executive to join Elias in Baltimore, along with Mejdal and director of pitching Chris Holt. Drew French, hired after last season as the O’s new pitching coach, is the sixth, pointing to Elias’ ability to develop relationships and attract talent to Baltimore.

Elias, Mejdal, and Rosenbaum provide the O’s with a unique brain trust.

“We all have areas that we specialize in,” Rosenbaum says. “So when you put our brains together, we kind of have everything in baseball covered. At the same time, we are all generalists. It’s not like you’re in one department and that’s what you do. Because ultimately, if you’re only good at one thing, you’re probably not going to be an effective leader in an organization. For example, Sig oversees the analytics department, but he also spends time in player development and working with our coaches. Mike comes from a scouting and draft background, as we know. I come from a scouting background and now oversee the day-to-day of the major-league operation, but the scouting background helps because I understand how players progress.”

If it seems like a lot of baseball executives come with Ivy League degrees, that’s true.

The rise of analytics and ever-growing financial stakes coincide with a dramatic increase in the number of alums from Ivy and other prestigious universities in teams’ front offices. According to ESPN, the percentage of Ivy League graduates holding a franchise’s top decision-making position rose from 3 percent in 2001 to 43 percent by 2020. If you include the percentage of graduates from the top quarter of U.S. colleges, the number rises from 24 percent to 67 percent.

This rise, ESPN reports, coincides with a nearly 50-percent drop in former players running front offices.

The bottom line is that the nature of data-driven scouting, player development, and playing of the game, not to mention the financial stakes, has changed so much over the past two decades that it is demanding and attracting a new breed of front-office talent.

“I hate saying analytics so much, but when the quantitative component is combined with the increase in the amount of money involved, it’s made the job extremely complex,” Elias said. “If you’re only a baseball person and you have no ability to do the other things, that’s not a great recipe.

“If you’re a numbers guy and a money guy, but you have no feel for baseball or how to talk to baseball people and everything that goes into playing the game, that’s not an easy way to go, either.”

In other words, you have to be a Mike Elias.