Sports

Ravens GM Eric DeCosta Always Gets His Man

The kid who dreamed of running a team now holds one of the most prestigious positions in the NFL, for which he knows when to be patient—and when to pounce.

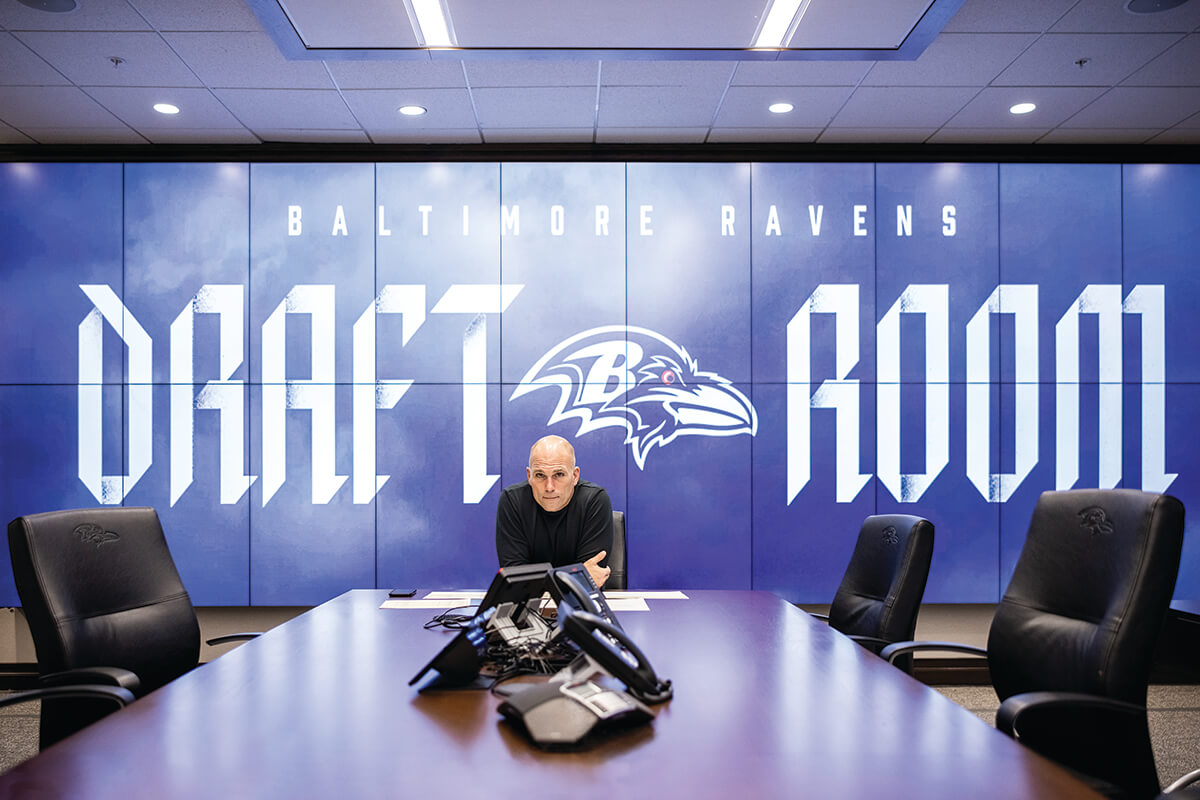

Four hours before the start of April’s NFL draft, Eric DeCosta and his staff gathered in a circle inside the Ravens’ Owings Mills war room. Per tradition, team chaplain Johnny Shelton led a group prayer. DeCosta has contributed to the organization’s draft process since he arrived as a fresh-faced intern in Baltimore the same year the franchise did. Now, as he prepared for his fifth draft as the team’s general manager, he was more emotional than usual during this annual ritual.

“I basically said, ‘If you have faith, you keep working, you trust people, there is always going to be hope,’” he recalls.

Minutes later, a cacophony of ringtones and phone vibrations filled the room, and the reason for DeCosta’s sentiment became clear: Lamar Jackson was signing a five-year contract extension with the team.

For the public, the superstar quarterback’s contract status had been a season-long melodrama simmering with the kind of juicy ingredients that the sports zeitgeist feeds on: trade demands and franchise tags, sprained ligaments and bruised egos, cryptic Tweets and mysterious memes. But behind the scenes, DeCosta navigated the two-year saga with a measured, drama-free steadiness that one person in particular seemed to appreciate.

“I didn’t have to learn anything about Eric,” Jackson said at the press conference announcing his extension. “He’s a businessman…he was professional the whole process. I was cool with it.”

DeCosta’s level-headedness and dogged determination—along with a keen eye for talent—have fueled his ascent from a 25-year-old personnel intern with an “office” in the hallway, a card table for a desk, and a salary south of $20,000 to one of the most prestigious positions in the NFL. Those are among the qualities that caught owner Steve Bisciotti’s eye more than a decade ago, when he told the then-little-known DeCosta that he wanted him to succeed legendary GM Ozzie Newsome and they’re what kept DeCosta in Baltimore even as ambition gnawed away at him.

Eventually, his patience was rewarded. Now, the kid who dreamed of running a team has a corner office with the only franchise he’s known in his professional life, in the city where he met his wife, Lacie, and where they’re raising their three kids. After an off-season in which he drafted receiver Zay Flowers in the first round, signed coveted (if mercurial) free agent wideout Odell Beckham Jr., and secured his All-Pro quarterback to throw to them, he believes he’s positioned the team for both short-and long-term success.

You could say that he’s cool with all of it.

He keeps the rejection letters in a bottom drawer of his desk, not out of anger or spite, but as a reminder that in a sea of nos, all it takes is a single yes. They came from virtually every NFL team, a cascade of, Thanks but no thanks and Don’t call us, we won’t call you.

And really, who could blame them? NFL bigwigs don’t come from places like Taunton, Massachusetts, the blue-collar town south of Boston where DeCosta grew up. As a kid, he played baseball, basketball, and hockey, but he was also drawn to the wonkier side of sports. After watching Dallas win Super Bowl XII in 1978, he became a Cowboys fan. For six-year-old Eric, that meant more than just watching the games.

“I studied the roster, I studied the front office, I studied the coaches, I studied their drafts,” he says, a hint of his New England accent still poking through. “The Cowboys built their team differently. They had a guy named Gil Brandt who was their scouting director. He was known for unearthing great football players at every level. That resonated with me.”

DeCosta’s father, Joe, who made bolts that were used for Navy subs, and his late mother, Donna, a bank manager, stressed academics. DeCosta has always been a voracious reader. He would devour The Boston Globe sports section and The Sporting News, examining mock drafts and creating his own. He didn’t play organized football until ninth grade, and although he found success on the field, he was lightly recruited in large part due to his slight stature. At 5-foot-9, 180 pounds, he was no one’s idea of a menacing defensive end or a punishing fullback, his two high school positions. Still, Colby College coach Tom Austin found a roster spot for him at the Division III program in Maine.

“We’re interviewing him and this young sprout from high school asked me, ‘Knowing that you’re in the process of rebuilding the program, is the college committed to football?’” Austin says. “It really took me back, because you don’t get those kinds of questions from a prospective.”

At Colby, DeCosta became a team leader, showing up for practice early, watching tape in the coaches’ offices, and calling out teammates who gave less than maximum effort.

“He was respected because he lived it,” teammate Gregg Suffredini told Colby News. “The kid could barely bench his weight, yet he was in the locker room every day…trying to get better, faster, stronger.”

“I LIKE URGENCY…SOMEBODY THAT PLAYS LIKE IT’S THEIR LAST PLAY EVERY TIME. ”

DeCosta’s football class at Colby was the first to graduate with a winning record in 33 years, but he was too savvy to fool himself into thinking he could play pro ball. So he decided to pursue coaching and landed a graduate coaching fellowship at tiny Trinity College, where he earned a master’s degree in English.

He thought he might be a writer until one day he ran into a friend who had just finished an internship with Washington’s NFL team. That inspired DeCosta to send letters and his resumé to every team. It wasn’t long before the floodgates of rejection opened. The responses ranged from businesslike to bizarre.

“While we appreciate your motivation, we do not have any openings at the present time nor do we anticipate any in the near future,” wrote Green Bay Packers GM Ron Wolf.

“Presently there are no positions available, nor are there any future changes contemplated,” the New York Giants put it. “We will keep your resumé on file and notify you if things change.”

Then, lest DeCosta had missed the screamingly obvious: “The thrust of this letter is one of pessimism…”

Twenty-eight of the league’s then-30 teams blew him off—but one that didn’t changed the arc of his life. Washington hired DeCosta as a training camp intern, and instantly, he was hooked. Wheeling TVs into meeting rooms, setting up phone lines—whatever the task, he attacked it with vigor. When the gig ended, DeCosta headed back to Trinity. He thought his NFL dreams were dead. He applied to law school at the University of Connecticut and was awaiting a decision when he got a call from the new NFL team in Maryland. His bosses in Washington had recommended him. Was he interested in a position?

“The day they offered me the job I remember I got the acceptance from UConn,” he says. “My mom wanted me to go to law school. My dad and I were playing tennis, and my dad said, ‘Eric, if your heart tells you to do this, you gotta do it.’ And he hesitated and said, ‘But don’t tell your mother I told you that.’”

DeCosta was Baltimore bound.

As an area scout for the Ravens, DeCosta was responsible for evaluating college players in 17 Midwestern states. He’d hop into his Pontiac in August and return in November with 30,000 more miles on the odometer. Early in his tenure, he brought tape of cornerback Duane Starks to Newsome, who ended up drafting the future stalwart in the first round.

“He has a passion for scouting,” Newsome says. “He’s not afraid to voice his opinion, but he’s able to listen to others and change his mind.”

DeCosta, who was named the team’s director of college scouting in 2003, has a distinct philosophy when it comes to analyzing players.

“I like urgency. Twitchiness. Guys that get from point A to point B quick and with anger,” he says. “I like guys that are physical and productive players. I don’t want to bet on guys. Sometimes I don’t have time for development—I’m looking for instant gratification. I want somebody that plays like it’s their last play every time, is quick to the ball, sudden, and plays with an element of physicality that others don’t play with.”

In 2007, DeCosta attended a party for Ravens front office staff and coaches at Caves Valley Golf Club in Owings Mills. Toward the end of the night, someone grabbed his arm. It was Bisciotti. The owner asked the scout to stick around for a drink. DeCosta didn’t know Bisciotti well and was “nervous as hell.”

DeCosta assumed other scouts would be there as well, but when he showed up to the bar, he found just Bisciotti and his wife, Renee. Over a bottle of wine, they discussed DeCosta’s future.

“He said, ‘You know, you remind me of me. I want you to be my general manager,’” DeCosta recalls, a hint of disbelief still registering in his voice even 16 years later. “He said he didn’t know when it will be but when Ozzie retires, you will be my next GM.” Then he pauses. “I didn’t expect to wait 12 years.”

By the time DeCosta became assistant general manager in 2012, the word was out in the NFL: He was a hot commodity. Seattle, Chicago, and Green Bay were among the teams that pursued him for a front office position, but DeCosta sat tight. He and his family were immersed in the community. Lacie is a Baltimore native, and he’s served on the board of the Maryland SPCA (where he’s still an ambassador) and the Irvine Nature Center.

Finally, in February 2018, Newsome made it official—he would be stepping down at the end of the season. Bisciotti announced that DeCosta would become the team’s new GM. The owner said “everything” about DeCosta made him confident that he was ready for the job.

“I think he has learned from Ozzie,” Bisciotti said at the time. “I think he’s a great leader of the scouts. It’s Ozzie’s department, but most of the interaction with all the scouts is with Eric. I’ve seen the way he goes about the business, I’ve seen the way he’s embraced technology and analytics and I like working with him. There are people that are running other franchises because Eric wouldn’t take it.”

But the mentor and his protégé still had work to do. Before Newsome’s departure, DeCosta advocated for a quarterback whom he described as a “magician.”

“Every year he would be ahead of me in evaluating college prospects,” Newsome says. “He was doing a corner from North Carolina. He came to the office and said, ‘I want you to take a look at this.’ I said, ‘Okay,’ so he pulled up the play. It was Lamar Jackson throwing this post pattern…it was Louisville versus UNC. He said, ‘Did you think Lamar could make that throw?’ And I said, ‘I do now.’”

The Ravens did their homework on Jackson, interviewing him, bringing him to Baltimore, and soliciting opinions about him from their own coaches and others outside the organization. When the 2018 draft arrived, he was on their board—meaning, among the players they coveted—but they felt they could get him with a pick lower than the 16th, which they held. After trading down several times, they drafted tight end Hayden Hurst with the 25th pick. At that point, a Ravens official came into the war room and asked Newsome and DeCosta to go downstairs for the traditional press conference.

What transpired next seems like a scene straight from the Kevin Costner movie Draft Day. DeCosta looked at Newsome and said that they should probably stay upstairs. Philadelphia had the final pick of the first round, and he wanted to ask Eagles’ GM Howie Roseman about trading for it. Newsome gave him the green light.

“So I called Howie and said, ‘If our guy is there, we might want to trade back into the first round,” DeCosta says. “I said, ‘What are you guys looking for?’ He said, ‘We’ll take your second round pick this year and we’ll take your second round pick next year.’”

“IT’S HARD TO NEGOTIATE WITH A FRIEND OR SOMEONE THAT YOU REALLY RESPECT. ”

The men waited nervously while the remaining six teams selected. Had any other team seen the same potential in Jackson that they did? Finally, Philadelphia’s pick—the last of the first round—came. DeCosta quickly called Roseman back and consummated the trade. Lamar Jackson was a Raven.

The Ravens have gone 53-29 since that day; Jackson’s record as a starter is 45-16. He’s thrown for 12,209 yards and 101 touchdowns. Still, another number looms large: zero. That’s the number of Super Bowls the Ravens have been to with Jackson at QB.

DeCosta is undeterred. Signing Jackson to an extension that works for the quarterback and the franchise had been a top priority for years. Most players want to communicate via text these days, DeCosta says, but he also negotiated with Jackson face-to-face, one-on-one many times. (In an unconventional move, Jackson served as his own agent.)

“It’s hard to negotiate with a friend or someone that you really respect,” DeCosta says. “Anybody that’s been married knows that. It’s hard to be honest and truthful sometimes with people that you love because you think it might hurt them. I tried to be humble and honest and as transparent as possible. I tried to look at it from Lamar’s point of view, too. If you can do that, sometimes it makes it a lot easier to meet halfway or find a common ground. We all get so wrapped up in our own positions that we think it’s about us and them and we make it a competitive, confrontational thing. A negotiation doesn’t have to be that. It took a long time and there were many hurdles, but we got there.”

DeCosta’s office is a bit fancier than his original workspace in the hall. There’s a sitting area, a bookshelf (Blink, The Extra 2%, and Finding the Winning Edge are among the titles), and a Peloton in the corner. The bike, along with a new pastime—pickleball—are two of his post-pandemic obsessions. Lacie says hobbies are not her husband’s thing.

“Eric works seven days a week most of the year,” Lacie says. “He’s extremely devoted to giving all of his time to the team and to our kids. He really doesn’t have any other pastimes except pickleball.”

On the wall hangs the typed rejection letter the 23-year-old DeCosta got from the Packers’ Ron Wolf. Also framed is a handwritten note Wolf sent to DeCosta a quarter-century later, congratulating him on becoming the Ravens’ general manager.

“You are a testament to pa- tience and perseverance,” he wrote.

After the draft room erupted that momentous day in April, DeCosta retreated to his office, where he was soon joined by Ravens coach John Harbaugh, who brought a bottle of whiskey. The two took small celebratory sips.

“Alright,” DeCosta said after briefly savoring the spirit, “it’s time to get to work.”