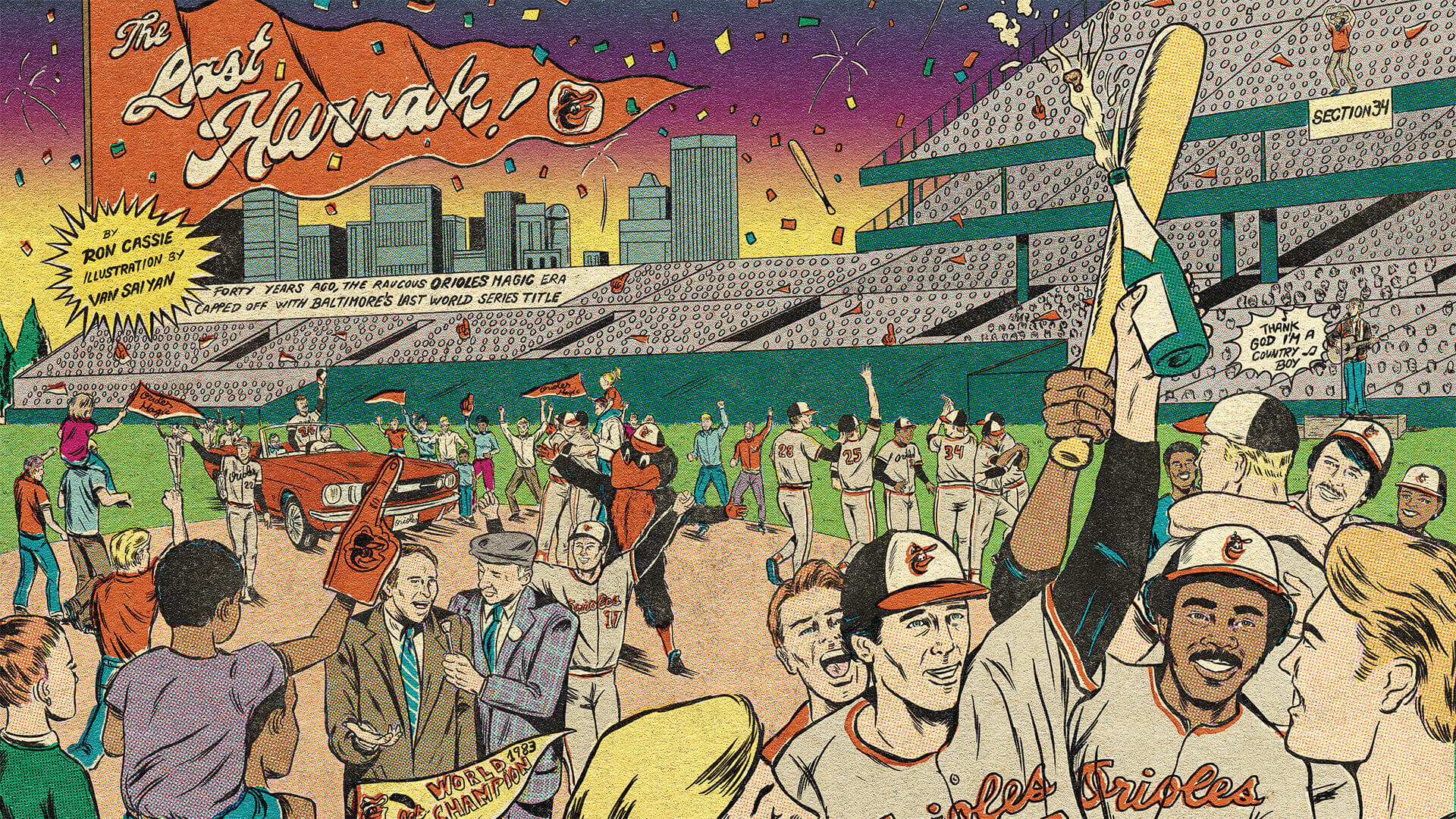

The Last Hurrah

Forty years ago, the raucous Orioles Magic era capped off with Baltimore's last World Series title.

By Ron Cassie

Illustration by Van Saiyan

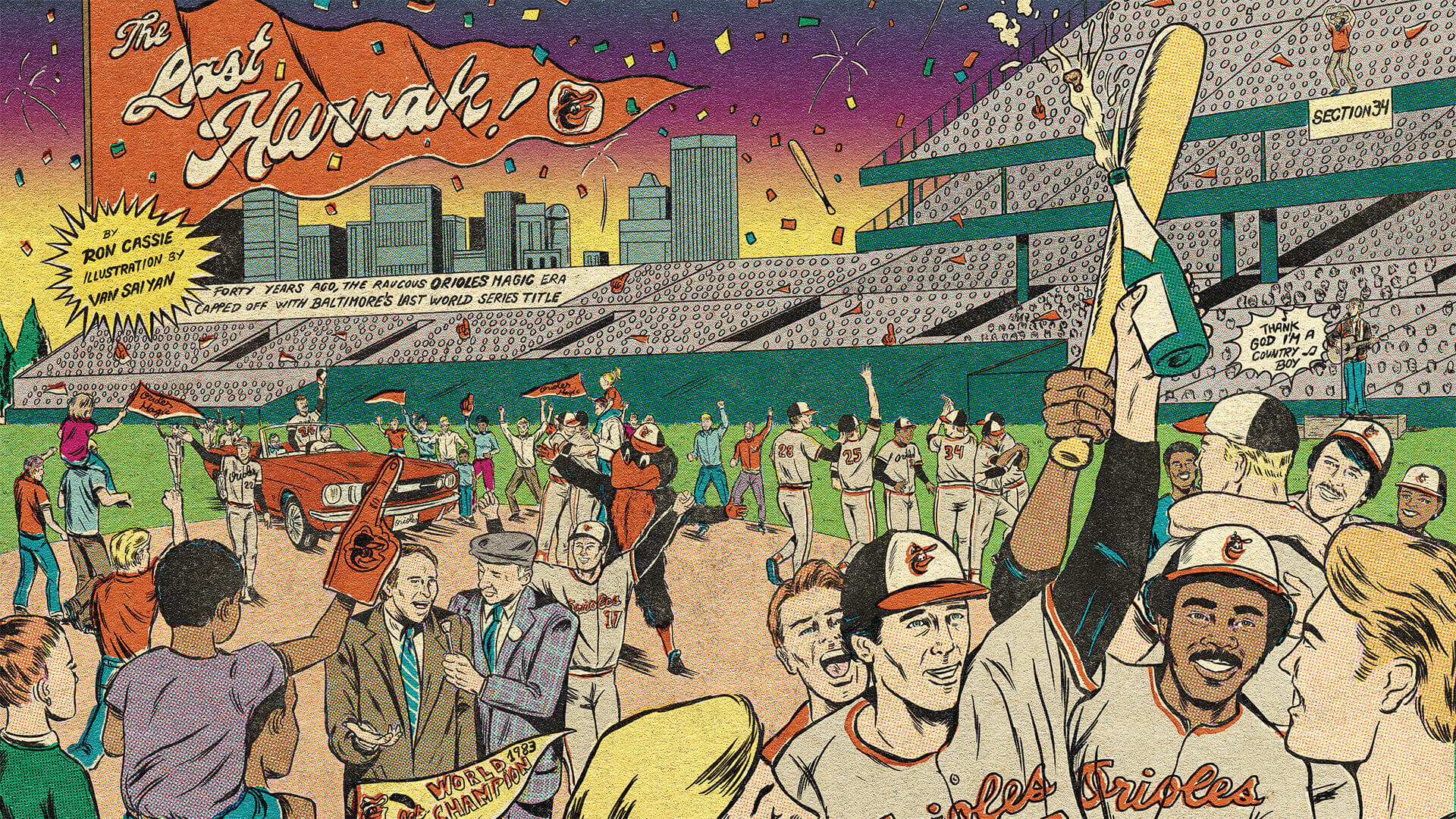

the visitors’ clubhouse at Philadelphia’s Veterans Stadium

before Game 5 of the 1983 World Series, Oriole

lefthander Scott McGregor did what starting pitchers

did in the days before digitized video: He analyzed the

pencil-kept pitching chart from his Game 1 start and recalled

the scouting report on each hitter. McGregor had been sharp in Game 1 at

Memorial Stadium, striking out six and walking none while allowing two runs

over eight innings. Nonetheless, he lost a 2-1 decision to eventual National

League Cy Young winner John Denny. That start followed a similarly well-pitched

2-1 loss to eventual American League Cy Young winner LaMarr Hoyt in

the opening game of the American League Championship Game. Playoff baseball

can be like that. Not unfair, just tough.

the visitors’ clubhouse at Philadelphia’s Veterans Stadium

before Game 5 of the 1983 World Series, Oriole

lefthander Scott McGregor did what starting pitchers

did in the days before digitized video: He analyzed the

pencil-kept pitching chart from his Game 1 start and recalled

the scouting report on each hitter. McGregor had been sharp in Game 1 at

Memorial Stadium, striking out six and walking none while allowing two runs

over eight innings. Nonetheless, he lost a 2-1 decision to eventual National

League Cy Young winner John Denny. That start followed a similarly well-pitched

2-1 loss to eventual American League Cy Young winner LaMarr Hoyt in

the opening game of the American League Championship Game. Playoff baseball

can be like that. Not unfair, just tough.

None of that was on McGregor’s mind, however. In fact, his father had been hurried into surgery the day before Game 5 because of an intestinal issue and he even managed to compartmentalize those concerns as he went over the Philadelphia lineup again with catcher Rick Dempsey. What was lurking in the 18-game winner’s mind, and the thoughts of his teammates, was 1979. Baltimoreans of a certain age need no reminder that the O’s had been up 3-1 in the World Series that year before dropping three straight games to the underdog, disco-inspired, “We Are Family” Pittsburgh Pirates. Unimaginable in today’s high-turnover free agency system, some 15 Orioles from that ’79 club were still with the team in ’83, including the hard-luck losing pitcher of Game 7.

Yes, despite allowing just two runs in eight innings in the deciding game of the 1979 World Series, McGregor had gotten saddled with that heartbreaking loss, too.

“You could’ve heard a pin drop in our locker room after we went up three games to one over the Phillies,” McGregor, 69, recalls 40 years later from O’s spring training camp in Sarasota. “We had a lot of guys who had been there before and we were all quiet, intense, and focused. We did not want to become another statistic—the team that lost two World Series after being up 3-1.”

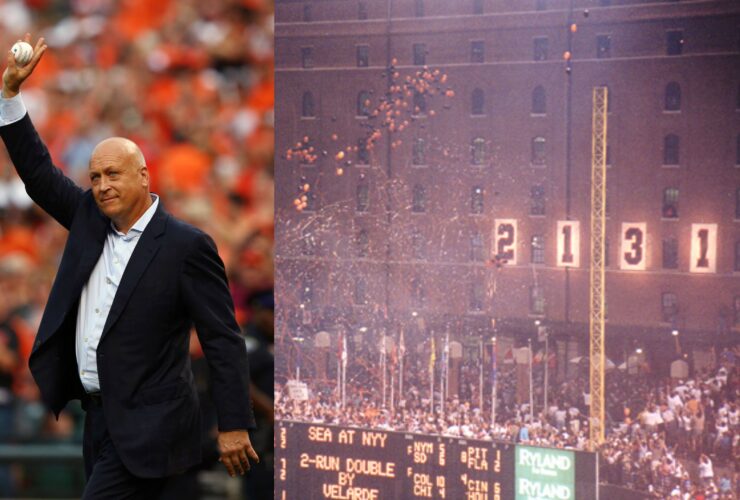

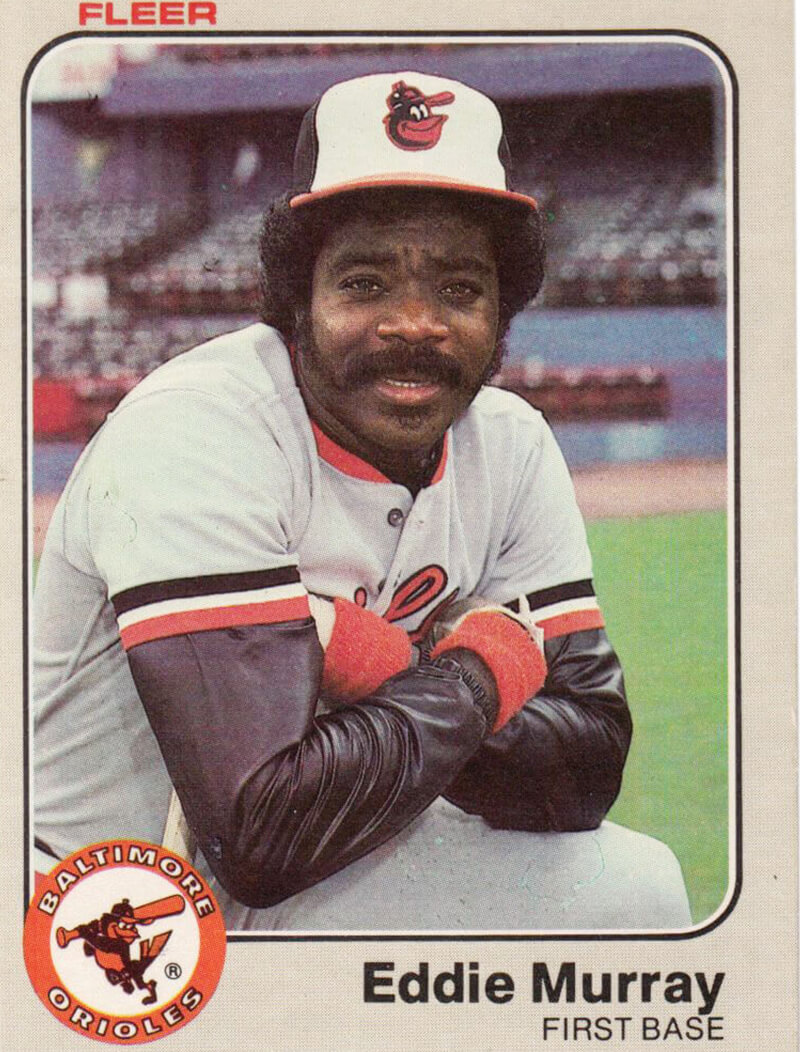

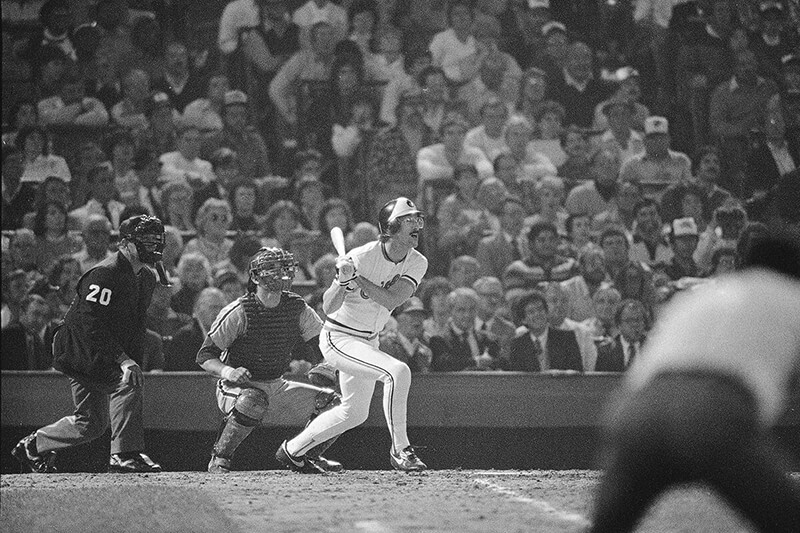

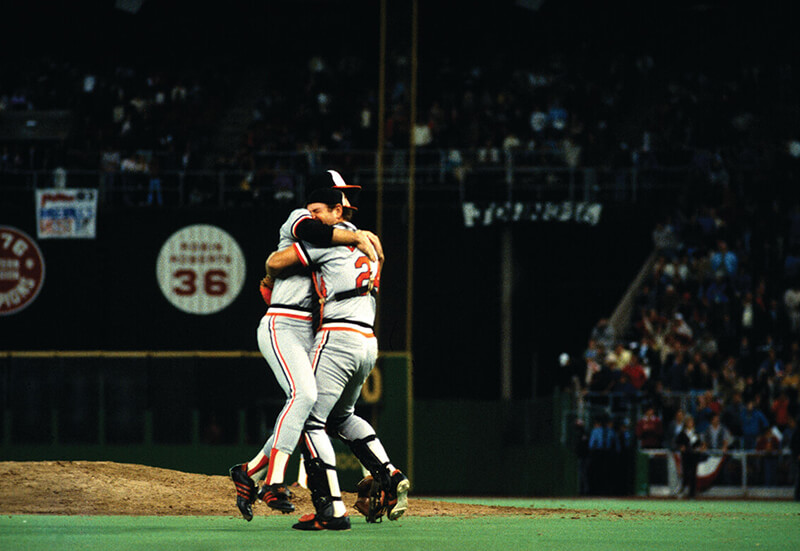

He had no reason to worry. Busting out of a World Series slump, Eddie Murray put the O’s up 1-0 in the second inning of Game 5 with a solo home run. Then Dempsey, the unlikely hitting star and MVP of the series, knocked one over the fence in the third. That was followed by a second Murray blast, this time with second-year shortstop Cal Ripken Jr. aboard, for a quick 4-0 Baltimore lead.

Fear of failure is often inhibiting, but it can also produce clutch performances. In the 5th, center fielder Al Bumbry drove in Dempsey with a sacrifice fly to make it 5-0, which held up the rest of the way. McGregor, who was masterful, left nothing to chance, going the distance and shutting out the Hall-of-Fame-laden Phillies lineup on five hits. “Sitting on the bench between the 8th and 9th—I don’t want to say I was rooting for our guys to make outs—but I hoped we’d go 1-2-3,” McGregor says. “I wanted to get right back out there and finish it off.”

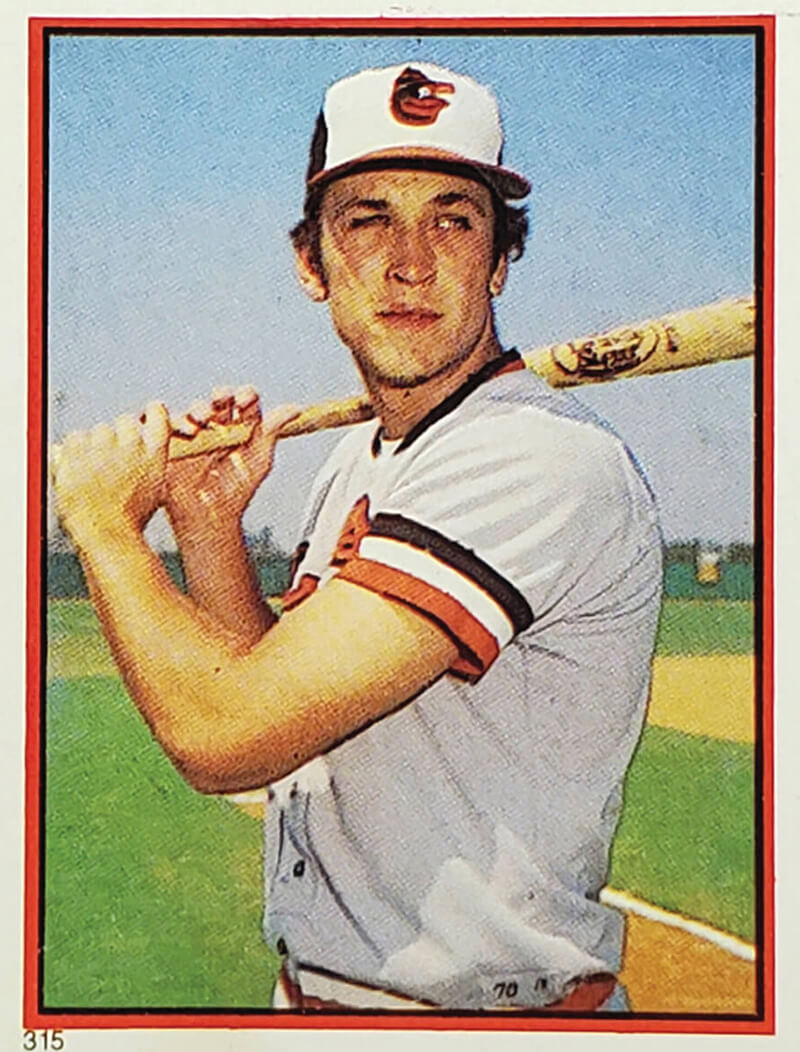

From top: Scott McGregor pitching in game 5 of the 1983 world series; Eddie Murray and Cal Ripken Jr. Baseball cards.—Courtesy of Donruss Baseball Cards

etween 1964 and 1983, the Orioles won

558 more games than they lost. They

won three World Series, upsetting the

Koufax- and Drysdale-led Dodgers in a

four-game sweep, dismantling Cincinnati’s Big Red

Machine in five games, and then routing the Mike

Schmidt-Steve Carlton Phillies again in five games.

They played in three other World Series and captured

eight American League or division pennants.

Since those halcyon days, our beloved Birds have

lost 430 more games than they’ve won. As every

long-suffering O’s fan knows, they haven’t been back

to the World Series since the culmination of that raucous

’79-’83 era, known as Orioles Magic, when a different

hero seemed to emerge every game, a bearded,

cowboy-hat wearing Dundalk cab driver named Wild

Bill Hagy led nightly cheers from Section 34, and

Memorial Stadium broke into chants of “Ed-dee! Ed-dee!

Ed-dee!” whenever their slugging first baseman

came to the plate with runners in scoring position.

etween 1964 and 1983, the Orioles won

558 more games than they lost. They

won three World Series, upsetting the

Koufax- and Drysdale-led Dodgers in a

four-game sweep, dismantling Cincinnati’s Big Red

Machine in five games, and then routing the Mike

Schmidt-Steve Carlton Phillies again in five games.

They played in three other World Series and captured

eight American League or division pennants.

Since those halcyon days, our beloved Birds have

lost 430 more games than they’ve won. As every

long-suffering O’s fan knows, they haven’t been back

to the World Series since the culmination of that raucous

’79-’83 era, known as Orioles Magic, when a different

hero seemed to emerge every game, a bearded,

cowboy-hat wearing Dundalk cab driver named Wild

Bill Hagy led nightly cheers from Section 34, and

Memorial Stadium broke into chants of “Ed-dee! Ed-dee!

Ed-dee!” whenever their slugging first baseman

came to the plate with runners in scoring position.

It had all begun with an improbable, two-out, come-from-behind walk-off home run by Doug DeCinces on a Friday night before 35,456 rowdy Baltimore fans on June 22, 1979. You really had to be there to understand the significance in O’s history of that seminal evening and how it cemented Baltimore baseball fans’ love affair with the team. Former O’s All-Star Ken Singleton, who would knock 35 out of the park that year and finish second in the AL MVP vote, remembers it like this: “We were down 5-3 to Detroit and I hit a home run to make 5-4 and Doug hit a two-run homer to win it and the place just went nuts. I think the fans learned they couldn’t leave the park early that night because something usually happened late in the game for us—and then we kept winning and winning and winning—102 games that year.”

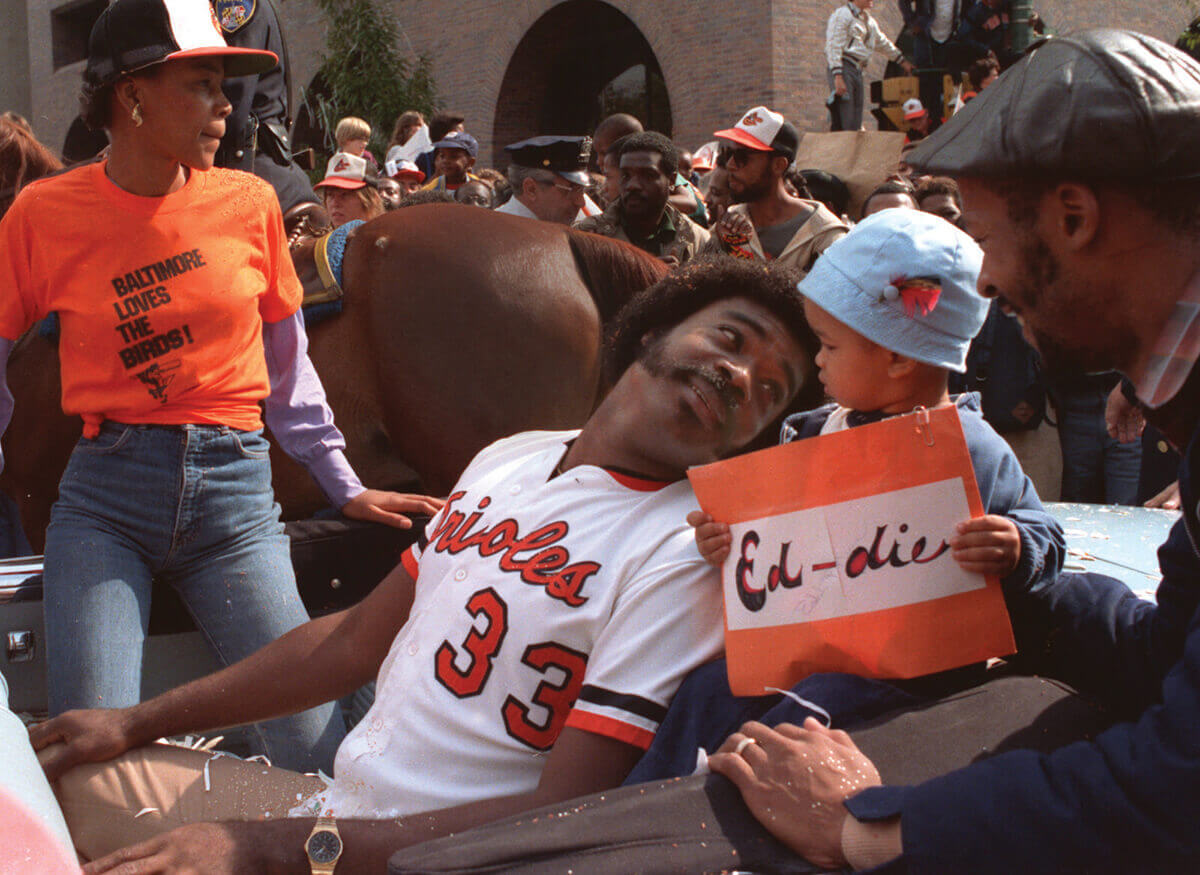

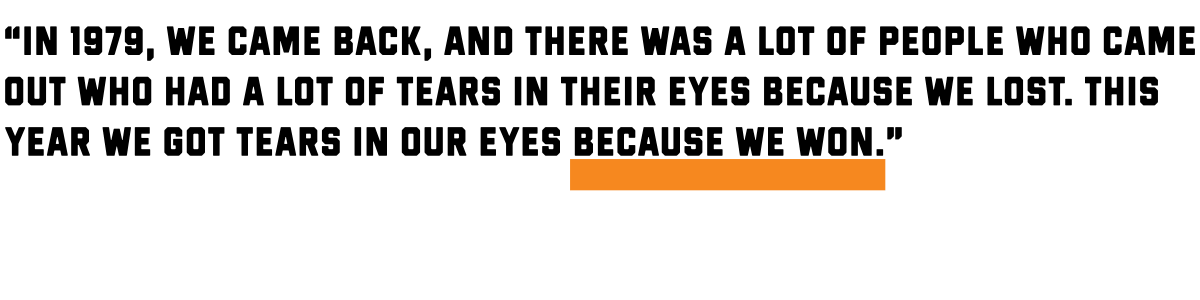

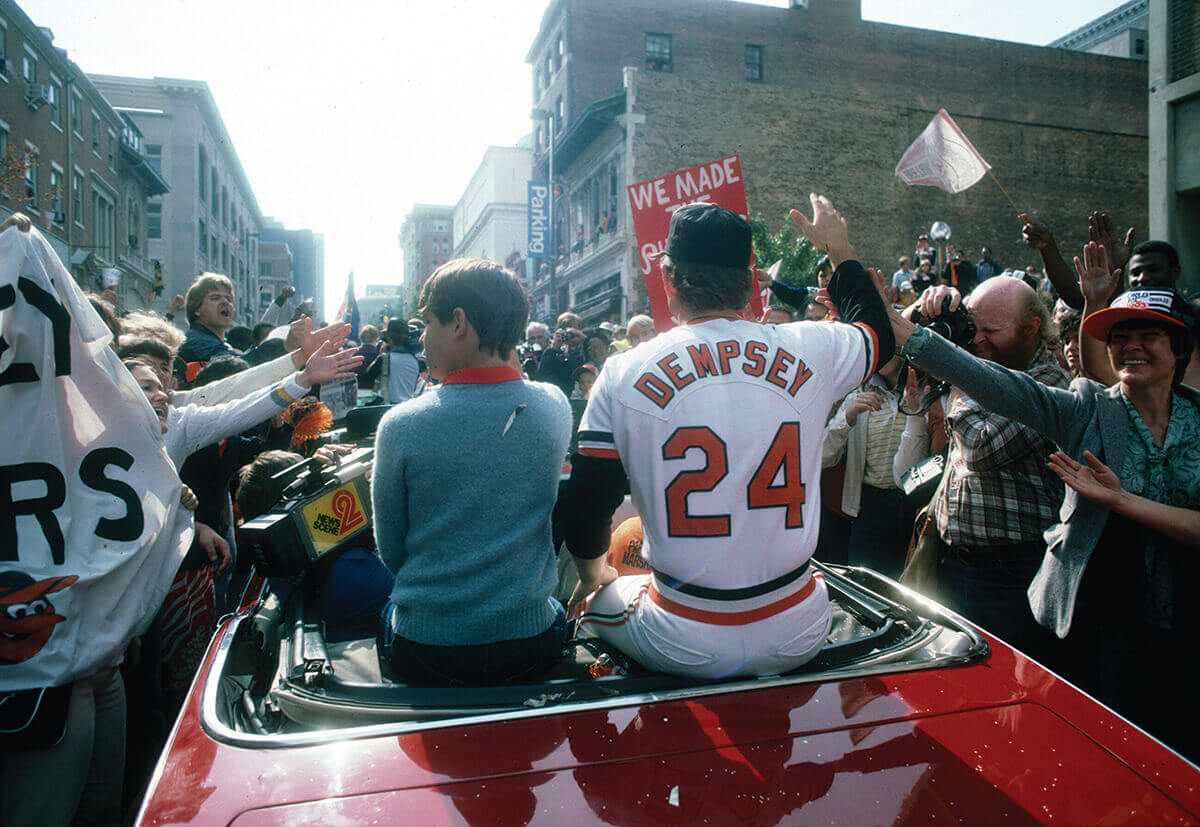

Eddie Murray meets an adoring young fan during the Orioles downtown parade.—Permission from Baltimore Sun Media. All Rights Reserved.

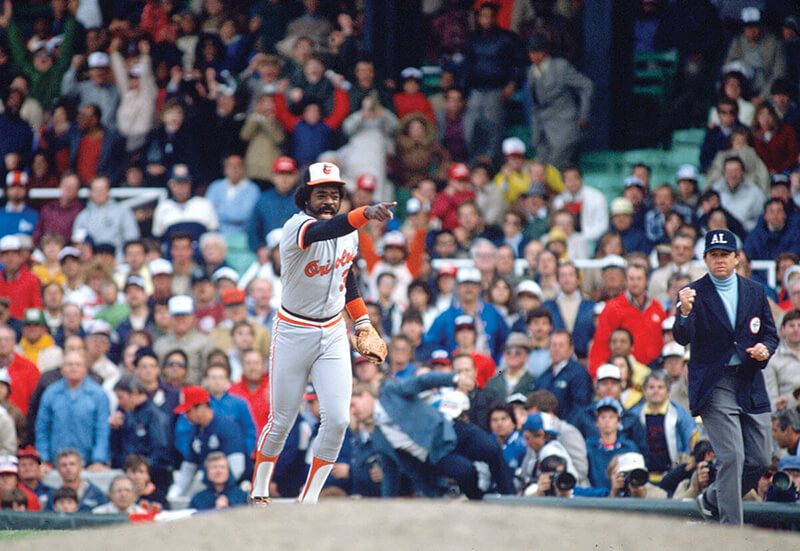

hroughout the entire 1960s and 1970s, the

Orioles had great starting pitching, played

Gold Glove defense, and hit three-run homers—their hallmark—winning more games

than any other team in baseball over those two decades.

But in truth, Baltimore at the time was still more of a

Colts town. The O’s struggled to draw a one million fans

annually, despite fielding legends named Brooks, Boog,

and Frank, and not one, two, or even three 20-game winners,

but four—the incomparable Jim Palmer, Dave McNally, Mike Cuellar, and Pat Dobson. They were also led

by a fiery, chain-smoking manager nicknamed the Earl of

Baltimore, whose operatic encounters with umpires were

worth the price of admission alone. It’s shocking, in hindsight,

the team hadn’t fully captured the imagination of

the Baltimore fans.

hroughout the entire 1960s and 1970s, the

Orioles had great starting pitching, played

Gold Glove defense, and hit three-run homers—their hallmark—winning more games

than any other team in baseball over those two decades.

But in truth, Baltimore at the time was still more of a

Colts town. The O’s struggled to draw a one million fans

annually, despite fielding legends named Brooks, Boog,

and Frank, and not one, two, or even three 20-game winners,

but four—the incomparable Jim Palmer, Dave McNally, Mike Cuellar, and Pat Dobson. They were also led

by a fiery, chain-smoking manager nicknamed the Earl of

Baltimore, whose operatic encounters with umpires were

worth the price of admission alone. It’s shocking, in hindsight,

the team hadn’t fully captured the imagination of

the Baltimore fans.

That all changed after DeCinces’ HR. More than a 1.6 million fans spun through the turnstiles that year in ’79, shattering the franchise record. It didn’t hurt that Colts owner Bob Irsay was busy leading that storied franchise into destruction. Four years later, in ’83, Orioles attendance topped more than two million for the first time. Combined with the opening of the nationally acclaimed Harborplace two years earlier, Baltimore felt like a city on the rise.

John Lowenstein watches his world series game 2 home run at memorial stadium. —AP Images

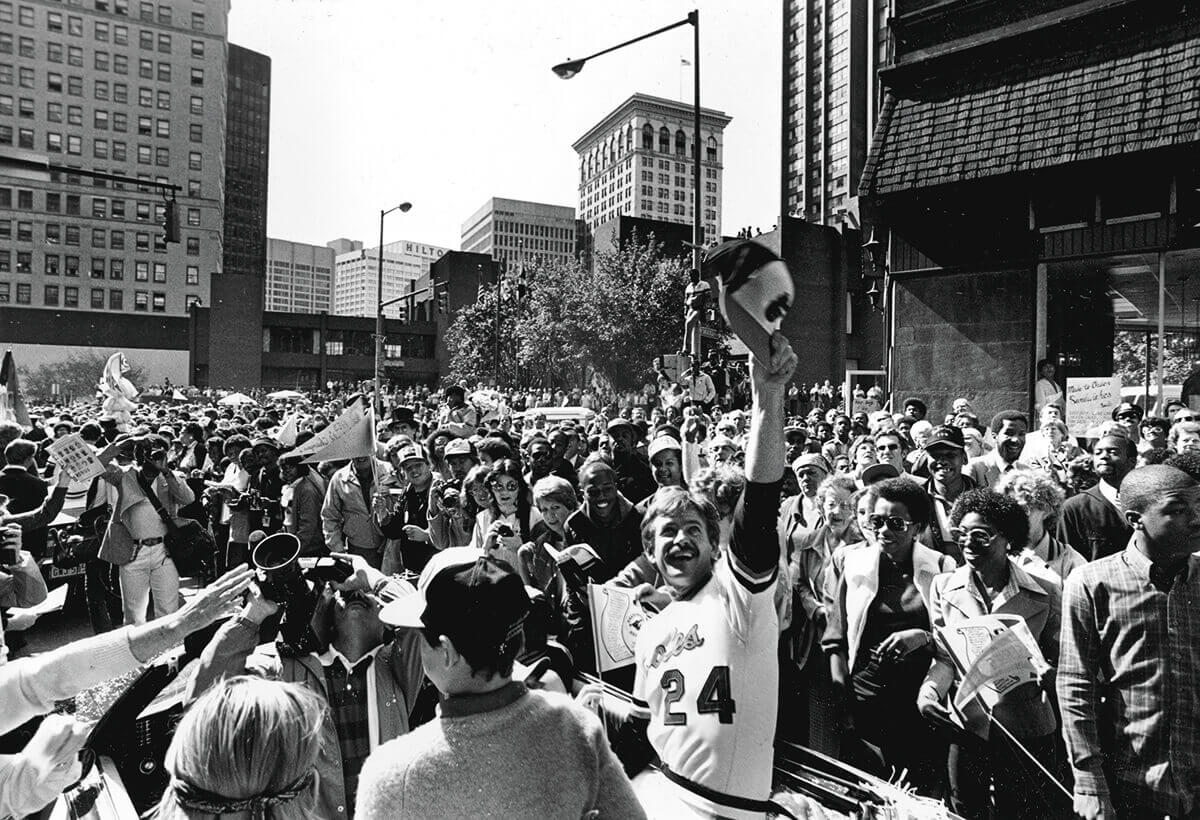

“We celebrated and all that after we won. But what I remember most is that because we were in Philadelphia‚ we bussed back that night to Baltimore,” says McGregor, who later served as a pitching coach in the organization and was invited down to spring training again this year as an advisor. “Every overpass had people with banners and signs, congratulating us. The closer we got to Baltimore, the more people were on the overpasses with banners and signs, and people began honking their horns. When we got to Memorial Stadium, there must have been 10,000 people in the parking lot alone. That was wild. So was the parade two days later.”

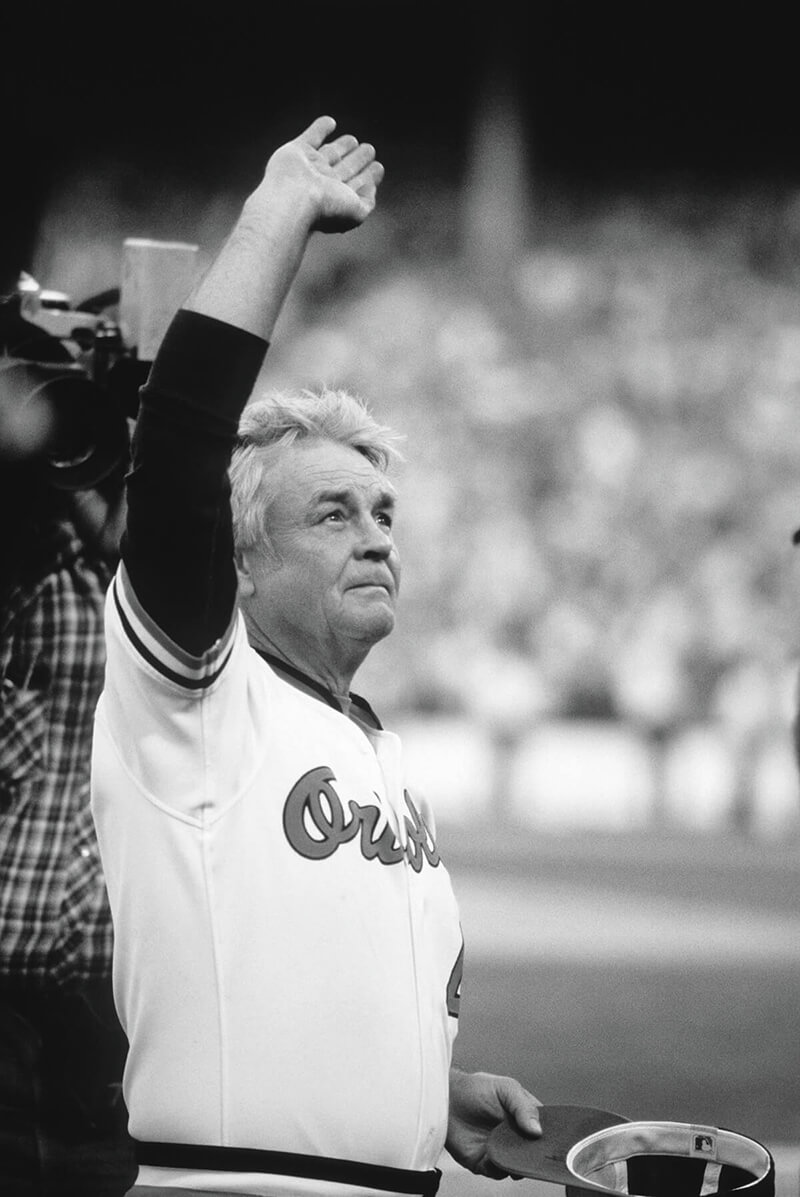

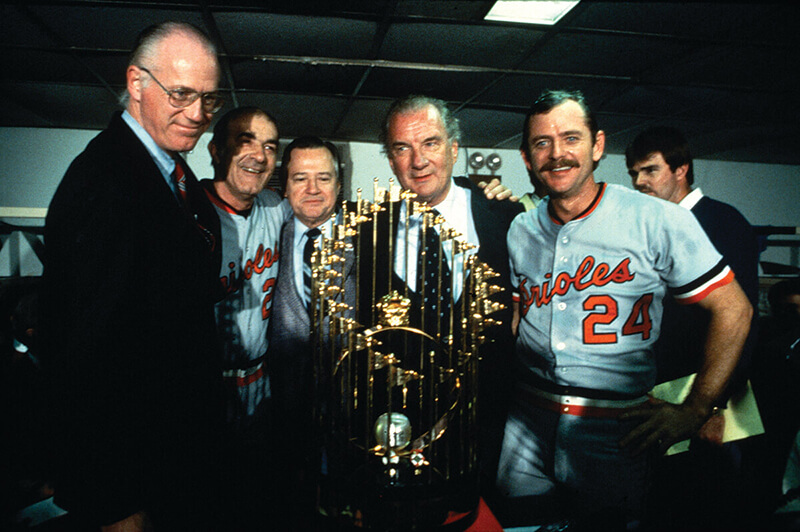

Police estimated 35,000-40,000 fans in total, counting those jamming the streets around the ballpark, welcomed the team home that night. An estimated 100,000 fans, leaving work early or taking Tuesday off altogether, turned out for the ticker tape parade two days later. It seemed like the good times, which had begun with the “Baby Birds” breakout season in 1960, would never end. But they did, rather abruptly. Although the 1983 O’s were not quite the collection of superstars those loaded ’69, ’70, and ’71 teams were (they were more a well-built roster of veterans and role players), none of those on hand for the parade could have predicted the harrowing descent that followed. Five short years later, the Orioles lost 21 straight to open the 1988 season, falling from model franchise to a Sports Illustrated cover symbol of futility.

“When I was there, they’d bring up at least one player [from minor league Rochester] that helped the team every year,” Singleton says, noting standout rookie pitcher Mike Boddicker was promoted when Jim Palmer went on the disabled list. But the farm system dried up. “Guys were aging, and the front office and ownership decided to go the free agent route and that didn’t work out. Then, they traded Eddie Murray, who I know wasn’t happy with the way things were going, but which I still think was a big mistake.”

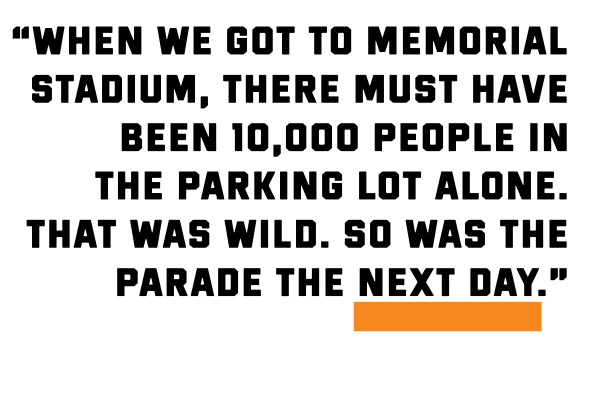

The orioles mob the pitchers mound at veterans stadium in Philadelphia after clinching the 1983 World Series.—Courtesy of the Baltimore Orioles.

arl Weaver had actually announced that

he would be retiring in the 1982 season

years before. Interestingly, it was not immediately

noted by The Baltimore Sun. At

least, the initial announcement isn’t found in a

search of their archives. Likely, the O’s beat reporters

were more concerned with the matter at hand, namely

the 1979 World Series. But Weaver’s announcement

was mentioned by The New York Times in a sidebar in

their sports section. Speaking before the sixth game

of the ’79 series at Memorial Stadium, Weaver said he

had originally planned to quit managing when his

contract expired after the 1980 season, but that the

rampant inflation of the past few years necessitated

he put in two more seasons in the dugout, “so I can be

comfortable until I get my baseball pension.”

arl Weaver had actually announced that

he would be retiring in the 1982 season

years before. Interestingly, it was not immediately

noted by The Baltimore Sun. At

least, the initial announcement isn’t found in a

search of their archives. Likely, the O’s beat reporters

were more concerned with the matter at hand, namely

the 1979 World Series. But Weaver’s announcement

was mentioned by The New York Times in a sidebar in

their sports section. Speaking before the sixth game

of the ’79 series at Memorial Stadium, Weaver said he

had originally planned to quit managing when his

contract expired after the 1980 season, but that the

rampant inflation of the past few years necessitated

he put in two more seasons in the dugout, “so I can be

comfortable until I get my baseball pension.”

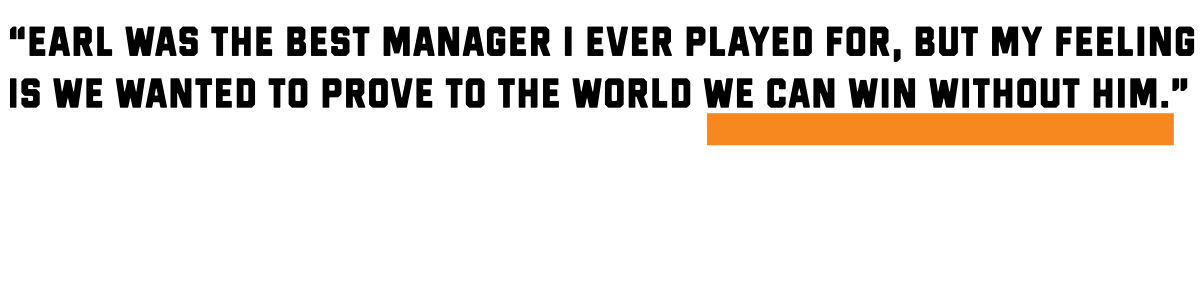

Longtime orioles Manager Earl Weaver Waving Goodbye to the Crowd at Memorial Stadium on the Last Day of the 1982 Season. —Getty Images.

“If I get in another three years, I’ll be lucky,” the then-49-year-old manager said. “Fifteen years with one club is a lot.”

A couple of days later, after Orioles bats had gone cold and they dropped the series to Willie Stargell and company, Weaver was named American League Manager of the Year by the Associated Press. It was the third time Weaver had won the award, having also earned the honor in ’73 and ’77, and deservedly so—the Birds had won a surprising 102 games in 1979, following a fourth-place finish in the AL East in 1978. In a story about the Manager of the Year Award, which was accompanied by a photograph of the skipper and his wife, Marianna, at their Perry Hall home, Sun reporter John W. Stewart finally added in the last paragraph that Weaver had said earlier in the week that he would “definitely” retire after the 1982 season.

A few days later, The New York Times followed up with an interview with Weaver. As Yankee partisans, we assume, the Times sports department was apparently quite interested in the machinations in Baltimore, which had battled the Bronx Bombers for American League supremacy for much of Weaver’s tenure. “This is a young man’s game,” Weaver said. “A lot of managers tend to stick around and get stale. I never want that to happen. I’ve made up my mind that wherever I am at the end of 1982, that’ll be all for Earl Weaver. I’ll be 52 then. In this game, that’s not early retirement.”

Top: Jim Dwyer scoring a key run in game 4. —AP Images.

Ultimately, the timing could not have proved more devastating and perhaps more perfect. Roaring back into contention over the last month of the ’82 regular season, the O’s needed to sweep the frontrunning Milwaukee Brewers in the season-finale four-game series at Memorial Stadium to make the playoffs. The Orioles took the first three games by a combined score of 26-7, and more than 51,000 fans packed the stands for Sunday’s game to witness either an AL East-clinching win—or Weaver’s last ballgame. Unfortunately, it proved the latter as the Brewers’ Robin Yount hit two home runs off Palmer, who had won 13 of 14 down the stretch in what would be his last big season. For more than 20 minutes after the game, the Memorial Stadium crowd remained, pleading for a curtain call from Weaver, which finally came, eliciting a deafening crescendo of cheers. Howard Cosell, calling the game for ABC-TV—and granted, given to hyperbole—described the moment as “one of the most remarkable scenes maybe that you will ever see in sport.”

A month later, Joe Altobelli, who could not have been more different than Weaver in terms of personality, was named manager. Altobelli had served a long managing apprenticeship in the O’s farm system, including six seasons in AAA Rochester, the O’s top farm club, before getting an offer to helm the San Francisco Giants. He subsequently led the Giants for three years with mixed results, but in his favor was his experience managing several key O’s players in Rochester and his two first-place finishes there. His low-key demeanor was also a welcome relief to the Orioles veterans, who knew how to prepare and play without Weaver’s haranguing. Plus, they still had the benefit of longtime O’s coach Cal Ripken Sr. and pitching guru Ray Miller in the dugout.

“Earl was a stickler on playing the game the right way and if you didn’t, he was on your case, there was none of this, ‘Wait around ‘til tomorrow to talk about it,’” says Singleton. “He was the best manager I ever played for, but my feeling was—and if you asked some of the guys, I think they’d say the say same thing—we wanted to prove to the world we can win without him. Joe was completely different. He had a veteran team and knew it. He just made out the lineup, let us play, and we won day after day until we eventually won the World Series.”

Commissioner Bowie Kuhn presents the World Series trophy to manager Joe Altobelli, O's owner Edward Bennett Williams, and catcher Rick Dempsey, the Series MVP.—COURTESY OF THE BALTIMORE ORIOLES.

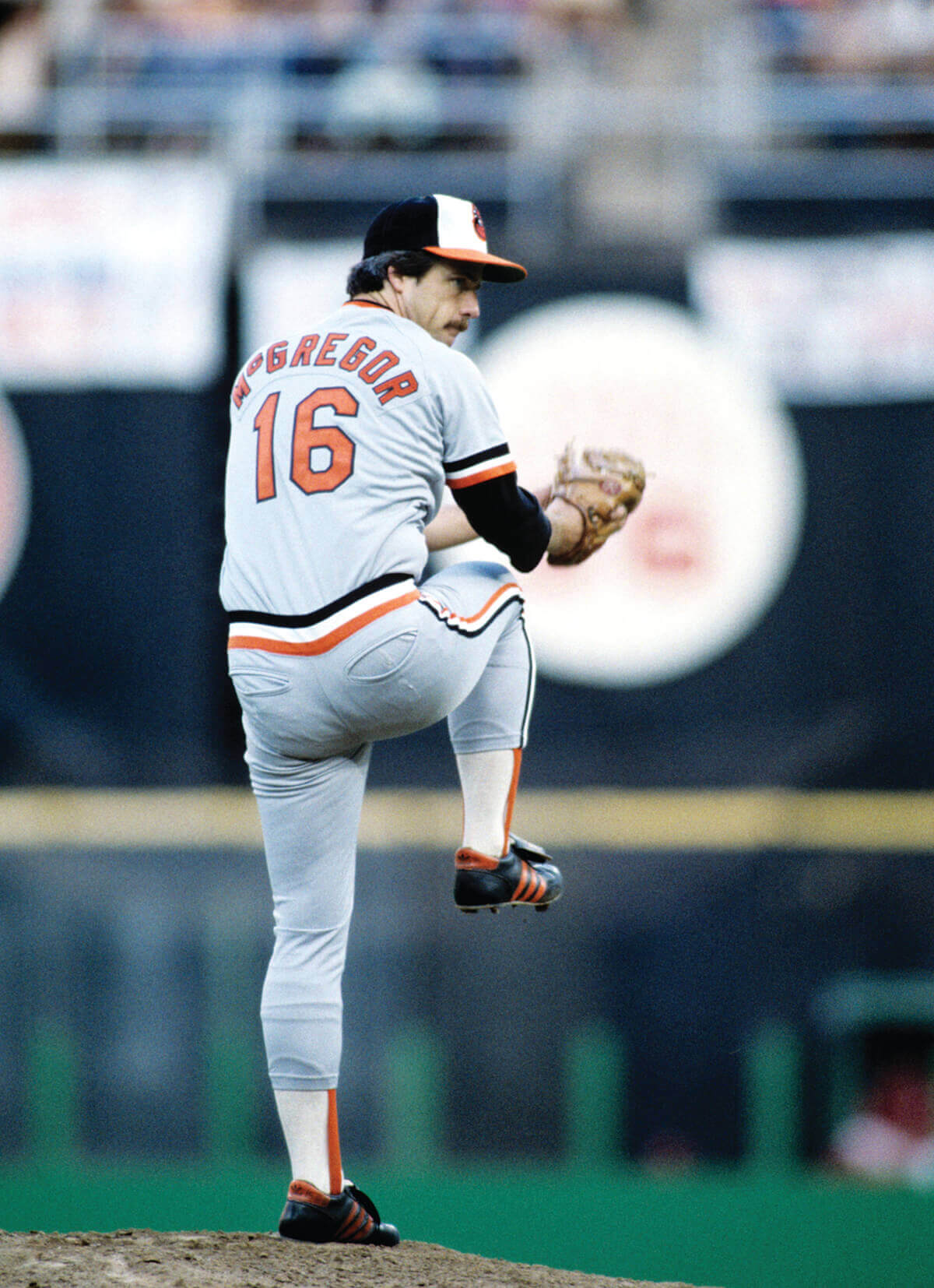

Proving they could make it without Earl was certainly some of the motivation for the 1983 season. But not a lot of extra motivation was needed after several years of frustration. Not only had the O’s failed to bring home a World Series title in 1979, in 1980 they’d won 100 games and still finished second in the division to the Yankees. In the split-season strike year of 1981, they’d finished two games back of the Yankees in the first half of the season and missed the playoffs. For many, including 36-year-old starters Bumbry, Singleton, and colorful John Lowenstein, as well as Palmer, the twilight of their careers had already arrived—they knew it. Dempsey, although he would play for many more years, including for the 1988 World Series-winning Dodgers, was 33. Right fielder Dan Ford was 31. Second baseman Rich Dauer was 30.

Orioles Catcher And 1983 World Series Mvp Rick Dempsey Tipping His Cap To Baltimore Fans At The City Parade Honoring The Team.—AP Images

Bumbry and Singleton, in particular, had worked hard to come back from injury-plagued campaigns in ’82. As soon as January arrived, the pitching staff began throwing under the supervision of bullpen coach Elrod Hendricks in the tunnels beneath Memorial Stadium. In fact, for the first time in a decade, the notorious slow-starting Birds got off to a winning record in April.

Then, the typical ups and downs of a 162-game baseball season arrived. Palmer spent much of the season out of commission. Mike Flanagan, who’d won the Cy Young in 1979, had gotten off to a 6-0 start, but was lost for a long period due to injury. Dennis Martinez, who had won 16 the year before, struggled all season. Star reliever Tippy Martinez missed three weeks with appendicitis. Ford, hitting .281 in mid-June, missed 25 games with an inflamed knee injury. Twice, they lost seven games in a row. None of it mattered—they battled back through it all.

Twenty-one-year-old Storm Davis, among others, rose to the occasion, logging 200 innings and going 13-7. Ultimately, it was two guys not with the team at the start of the season who solidified the pitching staff and defense. Boddicker won 16 games after joining the team in May. Mid-season pick-up Todd Cruz, a shortstop with tremendous range and a canon arm, was put at third base, lifting the infield play to an elite level.

Cruz also hit a homer and drove in six runs in his debut—always a good sign. Baseball players are nothing if not superstitious and when Tippy Martinez picked three Toronto Blue Jays off first base in one inning during the late August playoff race, the O’s had the look and spirit of a team of destiny. By the end of the season, they’d spent 118 days in first place, winning 98 games and besting the AL East runner-up Tigers by six games.

After winning the world series in 1966 and 1970, it took the orioles 13 years to win their third title—and their last to date. —Courtesy of the Baltimore Orioles

In the American League Championship Series, they dropped the opener to the White Sox, but then won three straight to advance—after another unsung hero, Tito Landrum, cracked a dramatic HR into a stiff Chicago wind at Comiskey Park.

Finally, it was Dempsey’s turn to provide the heroics. One of the very best, if not the best, defensive catchers of his generation, the gritty, fun-loving backstop was not known for his bat. But against Philadelphia, he set a record, which stands to this day, with five extra-base hits in a 5-game World Series. Almost everyone had at least one big moment, however. Backup centerfielder John Shelby, Cruz, Dauer, and Lowenstein, who hit a key HR, were the offensive stars in the O’s Game 2 win. In Game 3, Ford hit a home run and Palmer, coming out of the bullpen, picked up the win. In Game 4, Dauer and platoon right fielder Jim Dwyer delivered multi-hit games with Sammy Stewart tossing 2.1 innings of shutout relief.

They were not the 1927 Yankees, but the ’83 Orioles played selfless baseball and knew how to win— whether it was a pitching duel, a slugfest, or an endurance contest. “We had chemistry. It’s hard to explain, but you know it when you have it—you feel like you’re never out of a game,” says Dempsey. “You know, I have two World Series records. The one people know, the five extra-base hits in a 5-game series, and one no one does, which is that I’m the only World Series MVP that got pinch-hit for twice—both times by Ken Singleton. Ken was a DH at that point in his career and that was a year they weren’t using a DH in the World Series. At the plate, Ken did everything Cal and Eddie could do, but he never complained about not playing. That’s the kind of team we had.”

For what it’s worth, McGregor, Singleton, and Dempsey all see hope in the current crop of young Orioles, who put together their first winning season after five long rebuilding years, which included three 100-plus losing seasons.

Nearly all of the young O’s are homegrown, like in the glory days. In particular, Dempsey highlights the well-regarded rookie catcher Adley Rutschman, whose call-up last season kicked the whole team into a higher gear. “He’s the guy that I thought brought a competitive spirit and winning attitude and you could see was the guy trying to lift everyone else up,” Dempsey said.

“You need players like that. Leaders like that. Guys who play with some fire and aren’t thinking about their next contract and who they’re going to sign with.”

Forty years ago, things were different with the Orioles, Dempsey says. The team’s desire to win, he says, was palpable. As was the bond between the city and the team. He and other key members had been with the club since the mid-1970s. After beating the Phillies and arriving at Memorial Stadium near midnight, Dempsey and Rich Dauer made their way to the ad hoc stage and hugged each other as the crowd chanted “M-V-P.” Then Dempsey stepped to the microphone.

“In 1979, we came back [after losing the World Series to Pittsburgh], and there was a lot of people who came out who had a lot of tears in their eyes because we lost,” the catcher reminded the throng of Oriole diehards. “This year we got tears in our eyes because we won.”

“ED-DIE, ED-DIE, ED-DIE!”—Orioles’ Hall of Fame First Baseman Recalls Baltimore’s Last World Series Title

On the 40th anniversary of the Orioles’ 1983 World Series championship, we queried Eddie Murray, the O’s iconic, switch-hitting slugger, about his memories of that season. The following is a lightly edited version of that email Q&A:

How did you guys feel in spring training and going into Opening Day in 1983? After an epic late-season playoff bid, the team fell just short on the last day of the ’82 season, losing to the Milwaukee Brewers before a packed house at Memorial Stadium. And then of course Earl Weaver retired, and Joe Altobelli was named the new manager in the off-season. You couldn’t get any more confident than us that year coming in. We lost on the last day of the season in ’82 and I tell you—we really thought we were going to win. To lose that game, we just knew we were winning in ’83, and we actually came out and did exactly that. I think any coach could tell we believed in ourselves, and we did.

Was there also lingering disappointment from 1979, when the team lost the World Series to the Pirates, or from coming so close to the playoffs in ’80 and ’81, as well as ’82? The ‘82 season gave us all of the fuel we needed. We were really close at the end, and it was really disappointing. To get up 3-1 [in the World Series], and to lose, that was really tough. You just try to keep moving on and dust it off your shoulders.

In those Orioles Magic days, when the club was smashing attendance records at Memorial Stadium, what was the biggest reason for the team’s incredible success? The reason we won is because we really believed in what we were doing. You have to catch the ball in order to win, and you have to be able to pitch the ball. A lot of people would come in and would play us knowing we weren’t going to give them the game. It was going to be a tough game. We weren’t going to make a lot of errors—it was what Baltimore was known for. Teams had to go out there and play their complete game because we weren’t going to give it to them.

You were in a bit of a World Series slump going into what proved to be the decisive Game 5 in Philadelphia. As any O’s fan of a certain age recalls, you subsequently smashed two home runs to pace the series-clinching, 5-0 win. What were you thinking in the clubhouse beforehand, and what’s your recollection of that game? [Veteran second baseman] Richie Dauer comes over and says, “How you doing kid? How you doing?” And I say, “What do you mean, ‘How am I doing? I’m doing good.’” Then Richie starts running around the locker room yelling, “The kid’s guaranteed it! The kid’s guaranteed it.” I start yelling at Richie not to do that. But I go up to bat the first time and I hit a home run. I come in the dugout, shake everybody’s hand, sit down, and then I look at Richie and say, “Richie, that’s not it.” So, I go up to bat the second time, and I think I hit my name on the scoreboard. I come back in the dugout, shake everybody’s hand, and sit down and look down at the end of the bench and say, “Richie, that’s not it.” You don’t want people to know what’s hurting, but I only actually had one good swing [in me] batting right-handed. I turn to the end of the dugout and, when they bring in a left-handed pitcher, I look down the dugout and I say, “I’ve got one swing.” I get up to bat and I hit it out of the ballpark into the upper deck, but it just misses the foul pole by five feet. [Nearly, a third home run.] Then I say to myself “Oh god, that’s it. Now all I can do is poke the ball to right field.”

With the franchise in decline by the late-’80s, you were eventually traded, playing for the Dodgers, Mets, and Indians before about coming home to Baltimore and hitting your 500th home run at Camden Yards in 1996. Did it feel like a full circle moment for you like it did for the fans? Absolutely, but you’re glad to get it over. You’re just so close and glad to get there. I told Cal as soon as I came in the door that particular day, that I would hit it that day. He asked me why, and I said “Well, nobody had bothered me. Nobody has said anything about it today.” Then we were running our sprints early in the evening after batting practice to get ready for the game. I run my first sprint and I get back and I’m ready to run my second, and I see they’re showing something on the videoboard. I didn’t know it was the same day that Cal broke the record [the year before] for his consecutive games.

I also had to get it in under the 12 a.m. hour because we had rain that day. It was good to get it over with.

So, it’s been 40 years since the last ticker-tape parade for the Orioles, which was just an amazing scene and outpouring of affection for the team. We hope there will be another someday, the club finally seems on a solid trajectory, but how well do you remember that experience? The parade was outstanding. You could play this game a lot of years and not have a parade, so you won’t ever forget it. I can still remember somebody handed me a little kid that was on the car for a little bit with me. The parade is a moment that goes right along with the World Series—you don’t get many of those moments.