Sports

April 2021

The Birds Are Back in Town!

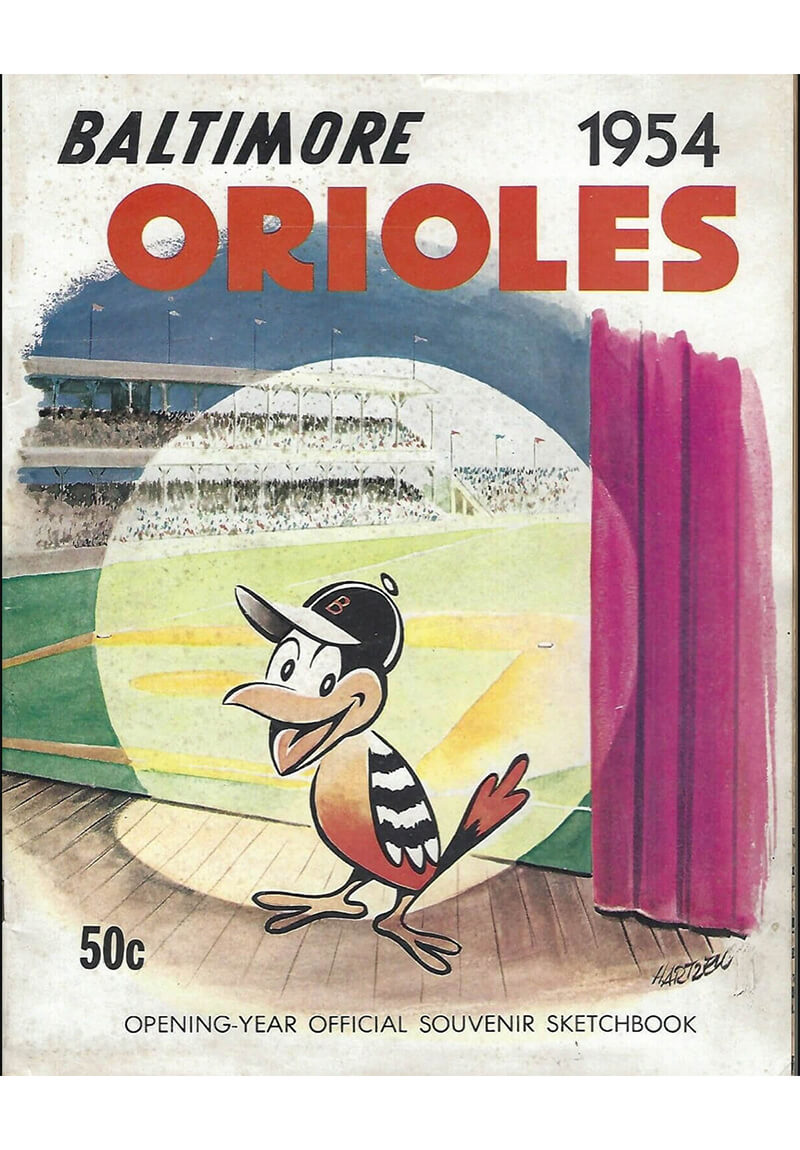

After 52 seasons without big-league baseball, opening day in ’54 was one for the ages.

THE OLD-TIMERS STILL TALKED ABOUT Wee Willie Keeler, his 45-game hitting streak, and the original Orioles of the 1890s. Those colorful, spikes-sharpened brawlers had brought diamond glory to Baltimore, capturing consecutive pennants in 1894, 1895, and 1896, and winning back-to-back Temple Cups—the World Series of the era. There were few old-timers left, however, by the time big-league baseball finally returned to the city in 1954. The original O’s franchise had moved to New York after the 1902 season (where, cruel irony, they morphed into the Yankees). Incredibly, Baltimore, the birthplace of one of the game’s first great dynasties, had been without its own big-league club for more than half a century.

THE OLD-TIMERS STILL TALKED ABOUT Wee Willie Keeler, his 45-game hitting streak, and the original Orioles of the 1890s. Those colorful, spikes-sharpened brawlers had brought diamond glory to Baltimore, capturing consecutive pennants in 1894, 1895, and 1896, and winning back-to-back Temple Cups—the World Series of the era. There were few old-timers left, however, by the time big-league baseball finally returned to the city in 1954. The original O’s franchise had moved to New York after the 1902 season (where, cruel irony, they morphed into the Yankees). Incredibly, Baltimore, the birthplace of one of the game’s first great dynasties, had been without its own big-league club for more than half a century.

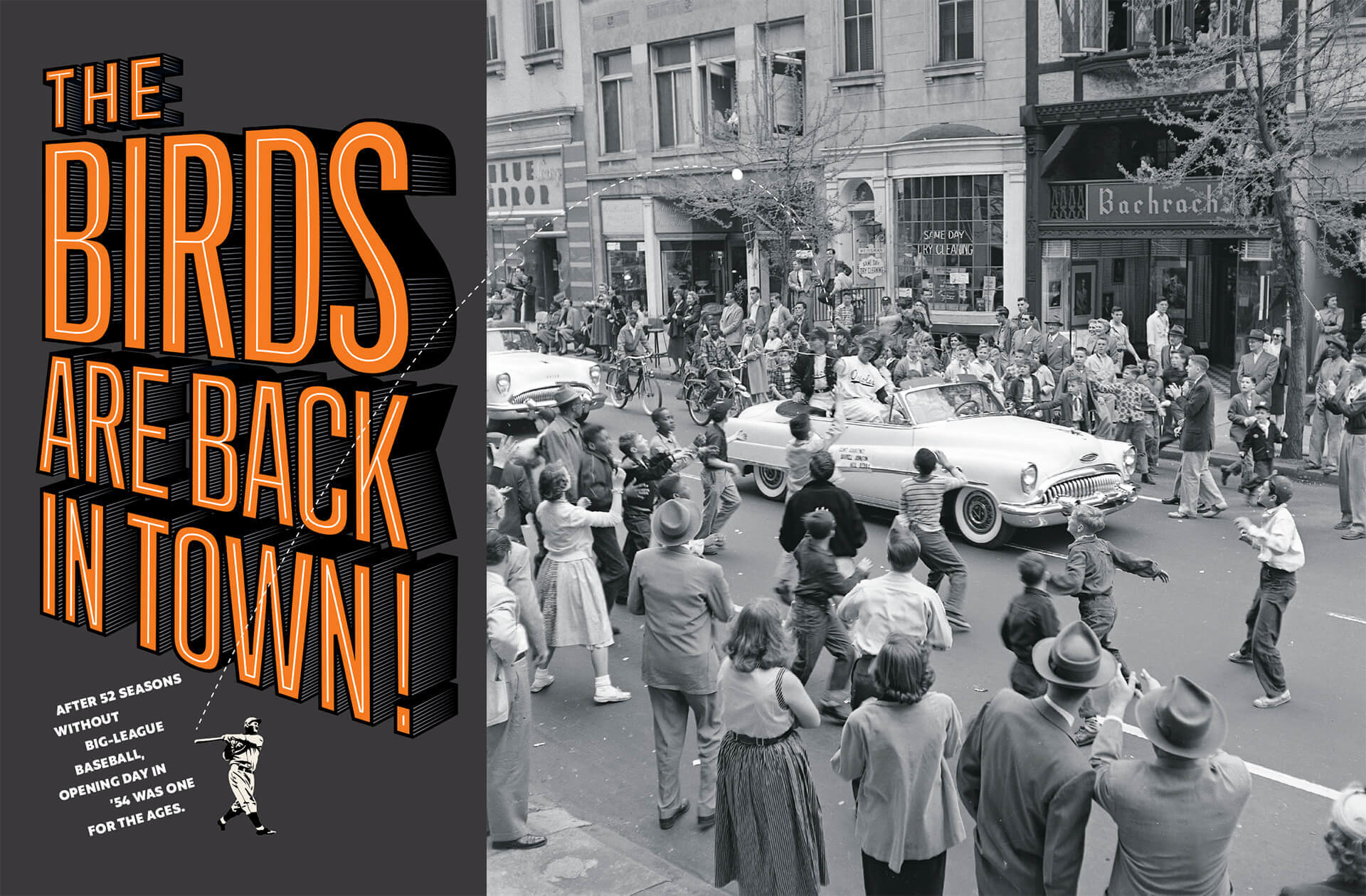

Still, throughout the first half of the 20th century, Baltimoreans continued to cherish their rich baseball heritage. Native son Babe Ruth started his professional career with what became the minor-league Orioles before starring for the Red Sox and then, of course, the damn Yankees. Lefty Grove, one of the game’s greatest pitchers, made his mark with the minor-league O’s, too. In the segregated ’20s, ’30s, and ’40s, the Black Sox and Elite Giants had produced Negro League championship teams here as well. And when big-league baseball officially returned on April 15, 1954, schools closed for the occasion, while city employees were given a half-day off. A massive throng, estimated at between 350,000 and 500,000 fans, jammed the Opening Day procession route from Camden Station—where the team had arrived by train from Detroit after splitting two games—up to Memorial Stadium in Waverly. None other than Blanche McGraw, the widow of 1890s O’s third baseman and Hall of Fame manager John McGraw, was on hand and exclaimed, “What a wonderful, wonderful parade! I wouldn’t have missed this for anything.”

There were two-dozen marching bands and floats, but it was the 11 convertible-carloads of ballplayers in their crisp white home uniforms that caused the biggest commotion. Kids clamored in the streets for the 20,000 plastic baseballs their new heroes tossed out to the crowd.

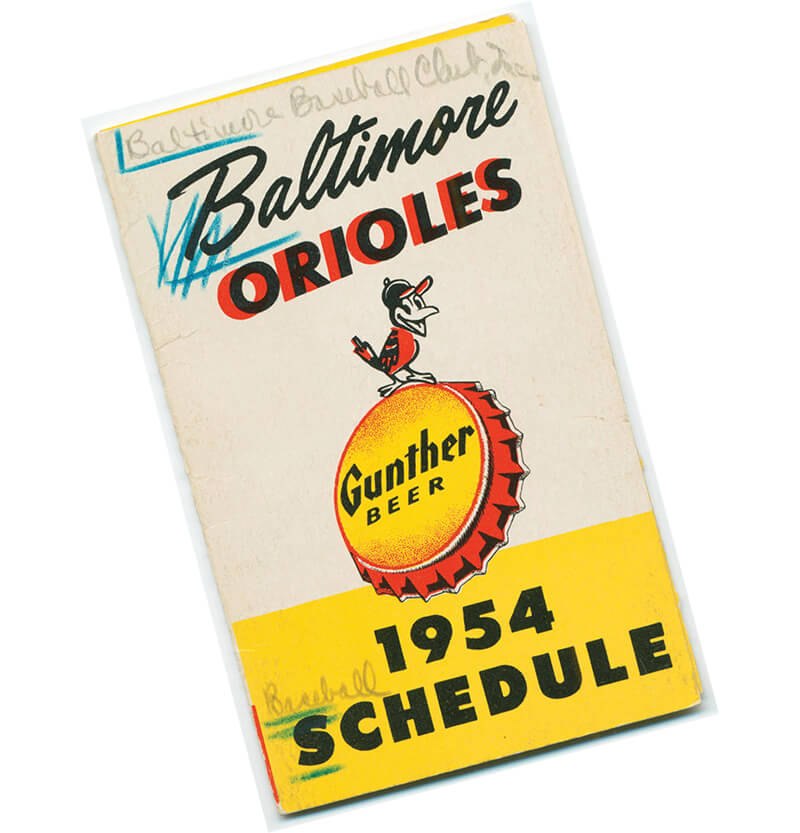

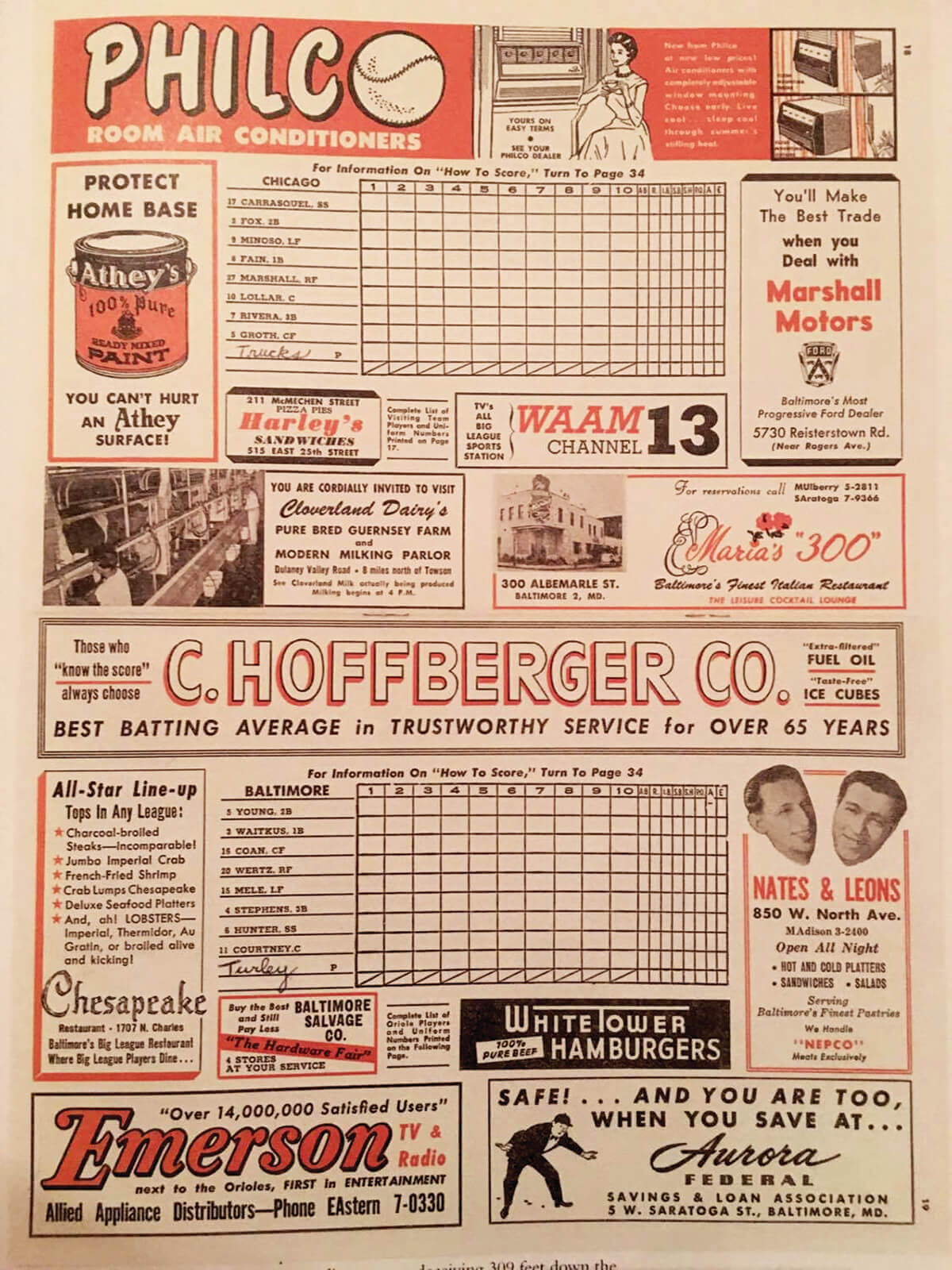

ORIOLES SCHEDULE OF HOME AND AWAY GAMES FOR THE 1954 SEASON. THAT FIRST SEASON, THE ORIOLES WON 54 AND LOST 100 GAMES, WINDING UP 57 GAMES BEHIND THE LEAGUE-LEADING CLEVELAND INDIANS. BALTIMORE ORIOLES 1954 SCHEDULE, BROCHURE BY GUNTHER BREWING CO., 1954, MARYLAND DEPT EPHEMERA COLLECTION, EPFL. COURTESY ENOCH PRATT FREE LIBRARY.

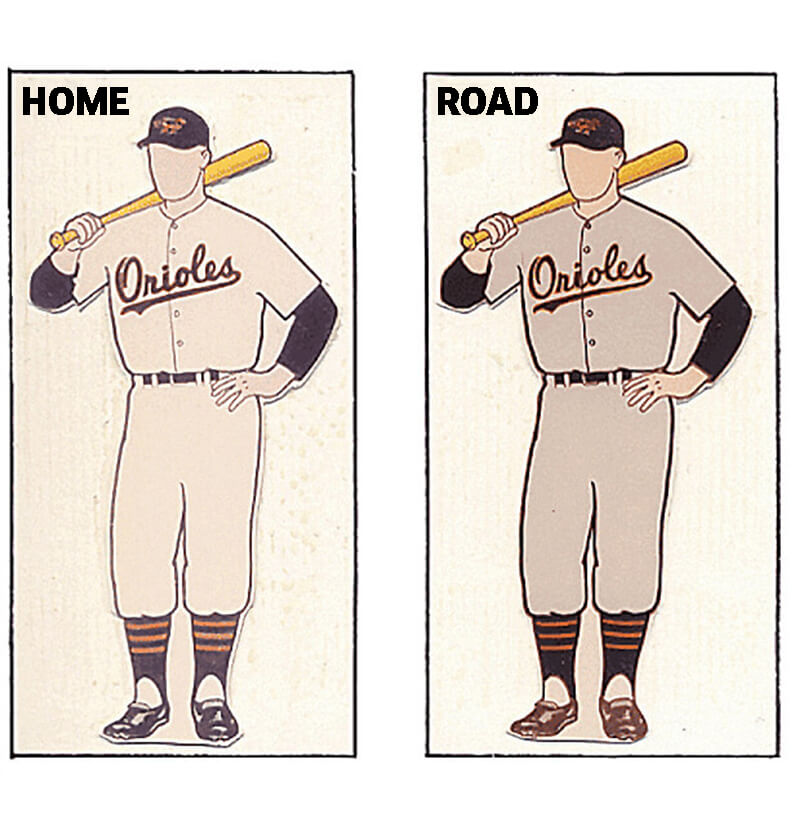

GRAPHIC ILLUSTRATION OF THE ORIOLES’ 1954 HOME AND AWAY UNIFORMS. BY MARC OKKONEN FOR THE ONLINE EXHIBIT, “DRESSED TO THE NINES, A HISTORY OF THE BASEBALL UNIFORM,” AT THE BASEBALL HALL OF FAME.COURTESY OF MARC OKKONEN.

“WHAT A WONDERFUL, WONDERFUL PARADE! I WOULDN’T HAVE MISSED THIS FOR ANYTHING.”

THE BALTIMORE SUN

Whether the new Orioles, relocating from St. Louis, where they lost 100 games in their final season as the historically inept Browns, would suddenly deliver a second Golden Age of Baseball in Baltimore wasn’t especially important. Not right away. What mattered in 1954 was that major-league baseball was back in town. That said, the first game at the reconstructed and rechristened Memorial Stadium played out to perfection. Twenty-three-year-old O’s starter “Bullet Bob” Turley went the distance, allowing just seven hits and one run while striking out nine Chicago White Sox. Clint Courtney, a squat, bespectacled catcher who resembled Harry Truman, hit the first-ever home run at Memorial Stadium in the third inning. In the fourth, former All-Star third baseman Vern Stephens crashed a second homer to carry the already-beloved Birds to a 3-1 victory before 46,354 euphoric fans. Thousands more had crammed into the city’s restaurants and bars, taking long lunch hours to catch the game on black-and-white television sets. “If they win this one,” one excited fan told a reporter, “they can have the town.” Downtown offices were universally described as “deserted,” while local department stores, with the TVs in their appliance sections tuned to the game, were “well patronized,” according to next day accounts in the Baltimore Sun.

In fact, after edging the Tigers the previous day, the O’s had put together a two-game winning streak and wrapped up their first home opener in 52 years in a three-way tie for the American League lead.

’54 FACTS

Memorial Stadium was still being reconfigured for big-league play, and its dimensions were extraordinary in 1954—446 feet to right-center, left-center, and straightaway center.

The only thing missing from the festivities had been Mayor Thomas D’Alesandro, Jr., who remained at Bon Secours Hospital for what was described as an extended “checkup and rest.” In his stead, Vice President Richard Nixon tossed out the ceremonial first pitch.

Two years earlier, D’Alesandro had joined forces with Clarence Miles, the founder of one of Baltimore’s prominent law firms, Miles & Stockbridge, to bring a major-league team to the city. “The culmination of a great dream,” said Miles, the team’s new president and chairman, of the first modern Opening Day, what has become our city’s unofficial civic holiday.

The Sun’s editorial board headlined the occasion “an auspicious beginning.”

“The biggest thing since beer came back,” said one excited O’s fan, linking the celebration to the repeal of Prohibition two decades prior.

“A MARRIAGE MADE IN HEAVEN, IT’S HARD TO IMAGINE ONE WITHOUT THE OTHER TODAY.”

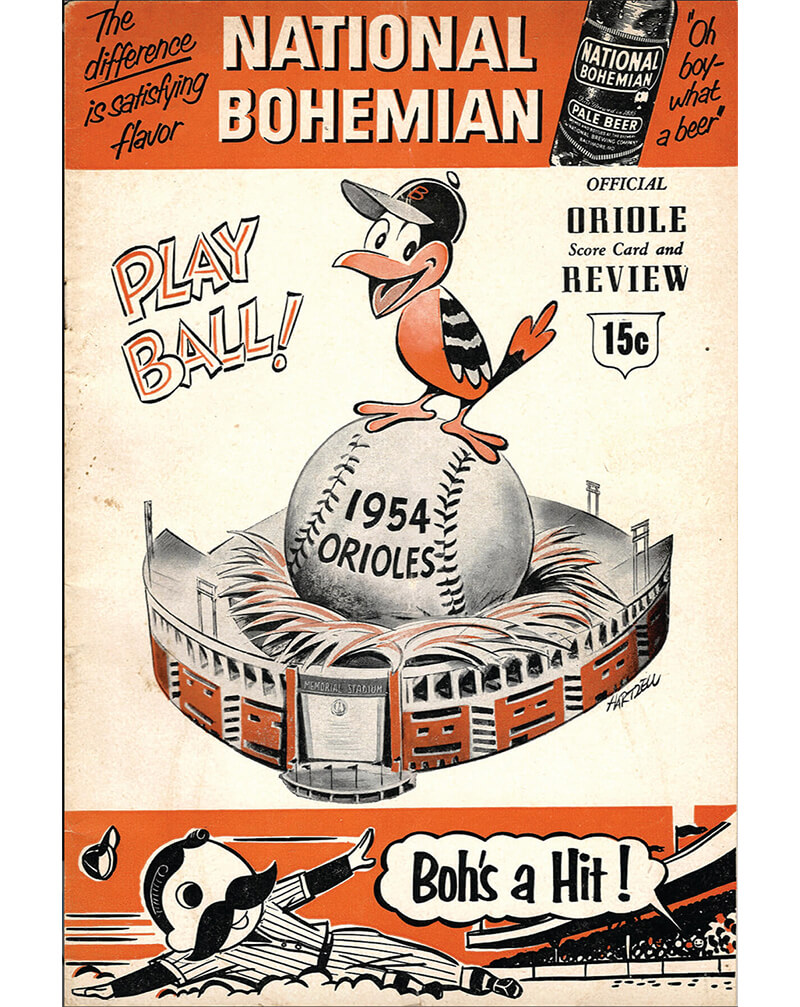

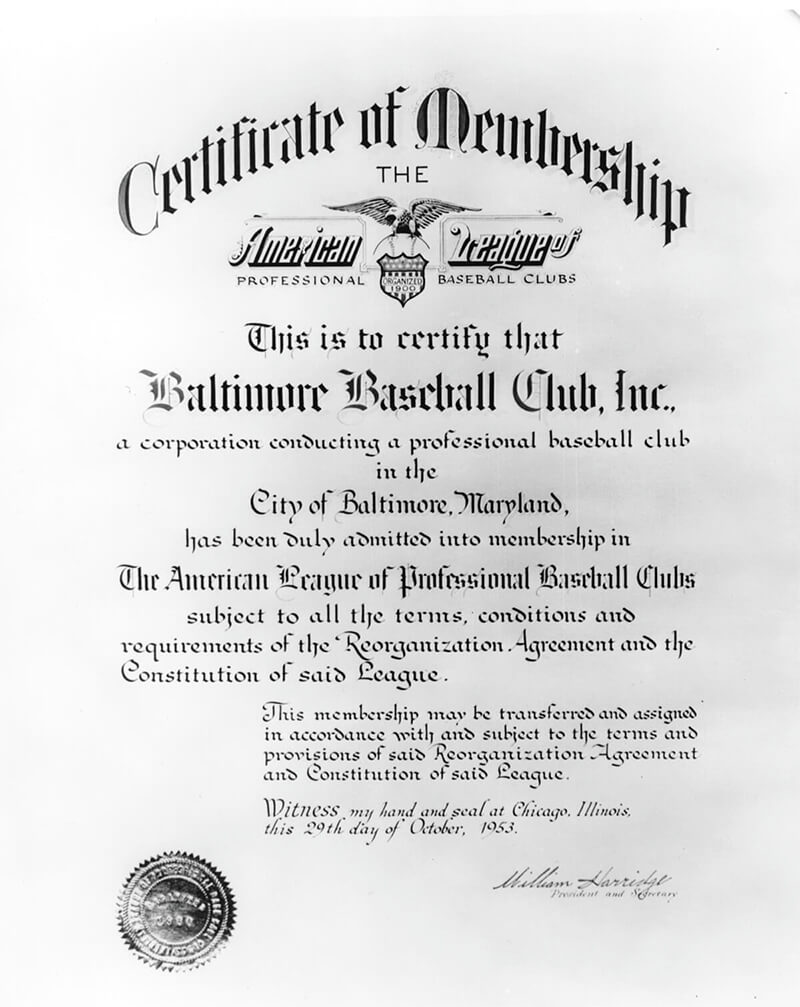

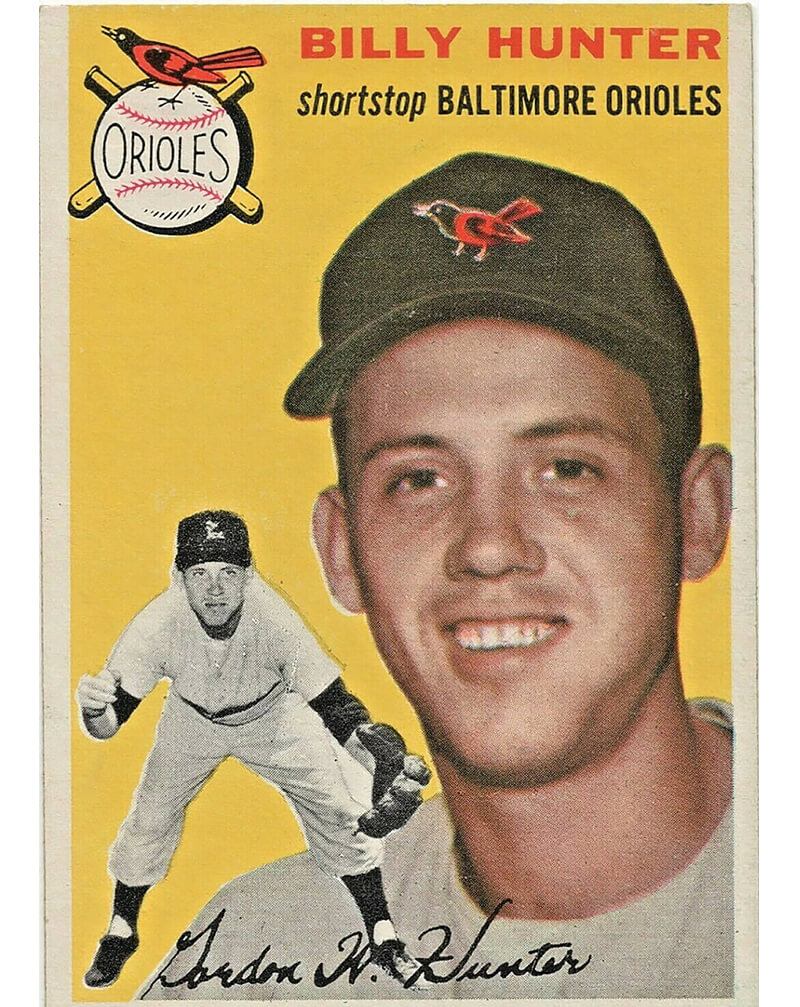

Clint courtney hits the first hr at memorial stadium, COURTESY OF THE BALTIMORE ORIOLES. o's scorecard, COURTESY OF THE SOCIETY FOR AMERICAN BASEBALL RESEARCH; certification of o's entry into the american league, COURTESY OF THE BALTIMORE ORIOLES; billy hunter's ’54 topps card, Courtesy of THE TOPPS COMPANY.

Luring a franchise to switch cities is a complex and fraught process, as Baltimoreans understand. Convincing St. Louis Browns owner Bill Veeck to sell his team to Baltimore ownership and getting the deal approved by the league’s owners (even though most did not care for Veeck) was no exception. Initially, the unconventional Browns owner—he once signed 3-foot-7-inch Eddie Gaedel as a pinch-hitter and later promoted the infamous Disco Demolition Night after gaining a controlling interest in the White Sox in 1970s—had hoped to dislodge the rival Cardinals from St. Louis. It looked like he might succeed, too, when their owner was convicted of tax evasion and the team appeared to be headed to Houston, before Anheuser-Busch put in a successful bid.

Recognizing he couldn’t compete with the brewing giant, Veeck then attempted to move his Browns to Milwaukee, the burgeoning “Beer Capital of the World.” But he was thwarted by fellow owners, who preferred the Boston Braves. Veeck next met with D’Alesandro and Miles, and after the 1953 season, they cut a deal. Under the initial plan, Veeck agreed to sell half of his 80 percent share to Baltimore investors, but remain principal owner. Despite assurances from American League president Will Harridge that approval was a formality, only half of the AL owners voted in favor. Reportedly, Yankees co-owner Del Webb was drumming up support for a Browns move to Los Angeles, where he held other business interests. Miles and D’Alesandro eventually realized, however, that the other owners had nixed the Baltimore proposal simply because they wanted Veeck out of baseball completely. Over the next three days, Miles lined up $2.5 million in additional funding to buy out Veeck’s stake. (To get an idea of how stressful the endeavor was, Miles subsequently spent two weeks in the hospital recovering from exhaustion.)

’54 FACTS

Born in Western Baltimore County, starting second baseman Bobby Young was a familiar face to local fans and one of the more popular early O’s.

Not surprisingly, given the symbiotic relationship between baseball and beer, Baltimore’s largest investor was Jerold Hoffberger, president of the National Brewing Company, makers of hometown favorite “Natty Boh.” A marriage made in heaven, it’s hard to imagine one without the other today. Hoffberger also helped quell the objections of Washington Senators owner Calvin Griffith, who held a potential veto given his team’s proximity to Baltimore, suggesting the brewery sponsor the Senators on radio and television. (A 56-foot National Bohemian sign shaped like a beer bottle stood, technically in play, next to the Griffith Field scoreboard until 1961.)

Other clubs on the move typically held on to their nicknames and team colors in an attempt to maintain a sense of franchise continuity, at least in the eyes of their owners, if not the fans. (Consider how little sense the onetime Brooklyn Trolley Dodgers made in Los Angeles.) In contrast, Baltimore’s owners immediately renamed the franchise the Orioles, an homage to the city’s storied baseball past, while also adopting the colors of the Maryland state bird. The relocation was also unique in that Baltimore’s wheelers and dealers had pulled a big-league franchise east. In the 1950s, the Dodgers (Brooklyn to Los Angeles), Giants (New York to San Francisco), Braves (Boston to Milwaukee), and Athletics (Philadelphia to Kansas City), all went west, chasing population trends.

’54 FACTS

Eddie Rommel, a Baltimore native and former pitcher who twice won 20 games for the Philadelphia A’s, was the home plate umpire at the ’54 home opener.

By the time D’Alesandro returned home by train from New York after helping ink the deal, the news had hit the papers. The mayor was greeted as a savior. Hundreds of baseball fans, not to mention the St. Leo’s School marching band from Little Italy, packed the lawn and concourse at Mount Royal Station as he disembarked to announce the agreement was official just weeks after the end of the ’53 season. “Welcome! A Hit!” read one sign. “Our 50-year dream has come true. Thanks to Tommy, Clarence.”

Spotting his wife Nancy in the crowd—it was their 25th anniversary—D’Alesandro described it as “one of the greatest days of my life.” He and Miles also left no doubt as to who had been most intent on submarining Baltimore’s chances. Apparently, not only did Del Webb wish to place the Browns in California rather than Maryland, he didn’t want another baseball club on the East Coast, period, believing that with seven teams at the time between Boston, New York, Philadelphia, and Washington, his Yankees had enough competition in the region.

Handed an old 1890s baseball bat from the original Orioles as a ceremonial gift after arriving back in Baltimore, D’Alesandro quipped: “You should’ve given this to me when I went up to New York.”

“WELCOME! A HIT! OUR 50-YEAR DREAM HAS COME TRUE. THANKS TO TOMMY, CLARENCE.”

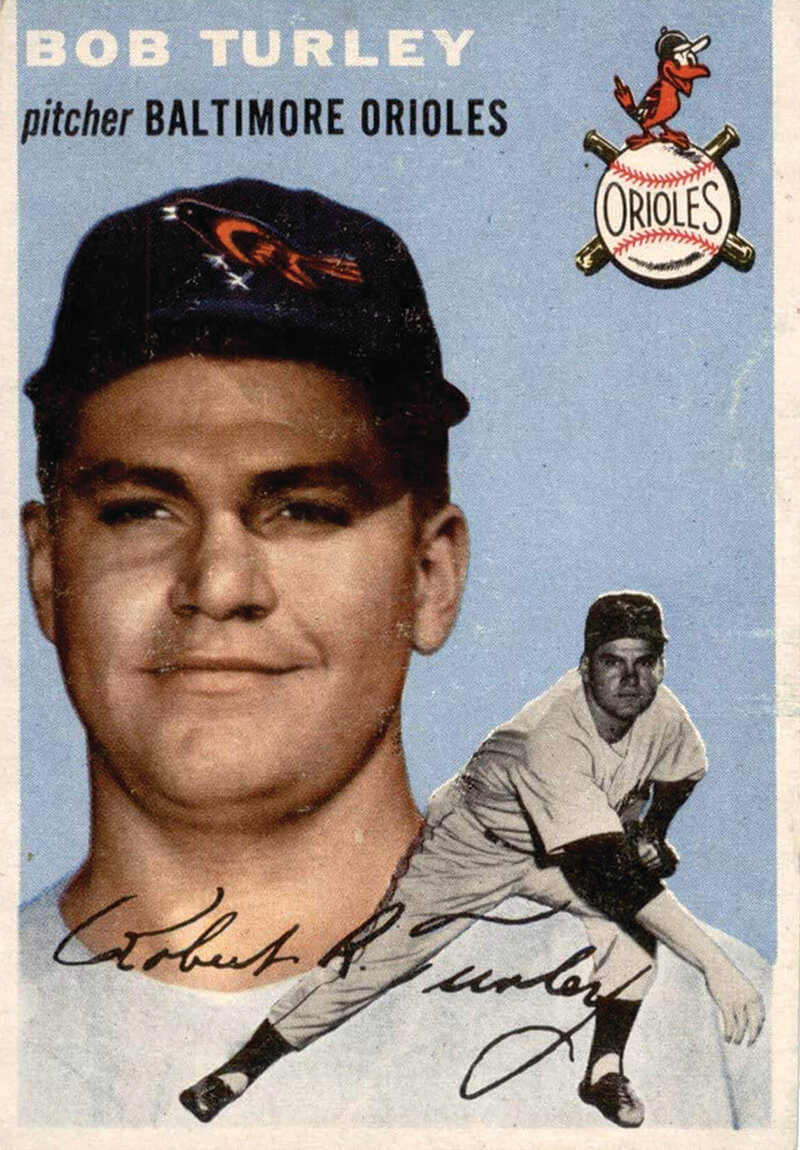

O’S MANAGER JIMMY DYKES, LOOKING SURPRISED BY ALL THE HOOPLA, RIDES IN THE OPENING DAY PARADE, 1954. PHOTO COURTESY OF AP IMAGES; BOB TURLEY’S 1954 TOPPS BASEBALL CARD COURTESY OF THE TOPPS COMPANY; ORIOLES 1954 OPENING DAY REPLICA SCORECARD, COURTESY OF THE BALTIMORE ORIOLES; A 1954 ORIOLES OPENING YEAR SOUVENIR SKETCHBOOK, COURTESY OF THE SOCIETY FOR AMERICAN BASEBALL RESEARCH.

“Do I remember? Are you kidding? I went to watch the parade coming up Charles Street, and I went to the game Opening Day,” says 85-year-old former Baltimore News-American and Sun baseball writer Jim Henneman, who still pens columns for Press Box. “I was all in.”

Then 18, Henneman recalls talk about the Browns coming to Baltimore had been “in the air” the year before during his senior year at Calvert Hall, where he had been a standout pitcher. “It was something the guys on the team talked about all the time.” Growing up in Ednor Gardens, three-and-a-half blocks from Memorial Stadium, he had worked in the then-minor league Orioles clubhouse while in high school. He’d scooped up a bleacher seat for the 1954 home opener as soon as tickets went on sale. “It was a spectacle,” he says. “It was an event. The AAA minor-league team in Baltimore always had a rabid fan base. It wasn’t unusual for them to draw 10,000 for a big weekday game, or 18,000 or 20,000 over a weekend, but this was different. It was sold out— the Orioles said they could’ve filled Memorial Stadium twice over—and you had a lot of VIPs who might not normally go to a game, but went there to see and be seen. I remember the Orioles’ two home runs and 3-1 score. Even more vividly, I remember watching Bob Turley take a no-hitter into the ninth inning against Cleveland in the first night game at Memorial Stadium in his next start.”

It’s worth noting the O’s lost that Turley no-hit bid a week after the opener. The hard-throwing righthander had allowed a single and a home run to all-stars Al Rosen and Larry Doby in the last frame and took a tough one-run loss. After starting their inaugural season 2-1, the Birds would not post a winning record again for the rest of the season. Nor for the next four years, in fact, until they started the 1958 season 2-0. The Orioles would lose exactly 100 games by the end of 1954, but a winning season had not been expected, and, strange as it may seem, was not the key stat for measuring that first campaign’s success. That was attendance.

’54 FACTS

Ernie Harwell, who would go on to call baseball games for 52 seasons, including 42 with the Detroit Tigers, served as the O’s play-by-play man from 1954-1959.

On the heels of a half-century without big-league ball, Baltimore needed to prove they were a legit major-league town more than anything else. “That first year, they got a pass on the field,” Henneman says. “The goal the whole year was to draw one million people—no small feat when you lose 100 games, but they did it. One of the stories I heard later was that the Orioles spun the turnstiles a few extra times toward the end of the season.”

MEMORIAL STADIUM’S ART-DECO FACADE AND UNIQUE LETTERING WAS ICONIC AND STOOD ALONE FOR A SHORT TIME EVEN AFTER THE REST OF THE STADIUM WAS TORN DOWN. Library of Congress

On the field, the 1954 Orioles were something akin to an expansion team. The agreement to bring the lowly Browns to Baltimore had come so late in 1953 that general manager Art Ehlers, a Baltimore native who had been working for the Philadelphia A’s, and manager Jimmy Dykes, recently fired by the A’s, had both been hired just a few months before pitchers and catchers were scheduled to report to spring training. Like most expansion clubs, the ’54 team was a mixture of has-beens and not-yets, which isn’t to say it wasn’t a memorable group. Eddie Waikus, for example, the team’s 34-year-old first baseman, had been shot years before in a Chicago hotel by a female stalker, an incident said to have inspired Bernard Malamud’s literary baseball classic The Natural. Veteran slugger Vic Wertz, from York, Pennsylvania, was traded during the season to Cleveland and later hit a blast in the World Series that Willie Mays turned into the most famous catch in baseball history. The aforementioned squat, glasses-wearing catcher, Clint Courtney, nicknamed as Scrap Iron around the league, was better known for his on-the-field brawls (including a pair of run-ins with the Yankees’ pugnacious Billy Martin) than his hitting prowess. Twenty-four-year-old Don Larsen, who would go 3-21 for the O’s in ’54, pitched what remains the only perfect World Series game two years later— for, who else, the Yankees. After the season, in a deal involving 17 players and still the biggest trade ever, the Orioles also sent Turley to the Yankees, where he won the Cy Young Award in 1958. In summary, Orioles fans’ long hatred of the Yankees is built into our DNA.

’54 FACTS

The Orioles’ biggest win of the 1954 season was a 10-0 shellacking of the New York Yankees on July 30 in front of 27,385 hometown fans.

What’s remarkable, however—despite the 100 losses and a roster quickly turned over from top to bottom—is that the key pieces for the Orioles’ subsequent 25-yearrun of excellence were in place by the end of that first year. Not that diehards need reminding, but from 1960 to 1985, the O’s would win six pennants, three World Series titles, and more regular season games than any other team in baseball, Bronx Bombers included. The key players weren’t in the dugout in 1954, but in the ownership box, the front office, and heading the farm system and scouting department.

Also true: During that very first offseason, the Orioles got a tip about the future cornerstone of the team, a certain 17-year-old Arkansas schoolboy named Brooks Robinson. (A prescient Sun headline the following year based on reports from the O’s winter league manager in South America: “Birds May Be O.K. At Third.”)

Toward the end of the 1954 season, the O’s fledgling ownership group made a bold move that set the course of the franchise for the ensuing quarter-century. In a stroke of impatience and genius, with nine games left on the schedule, they lured manager Paul Richards away from the Chicago White Sox. (The same team the O’s beat in their home opener to begin the year.) Remarkably, the owners pried Richards loose from the Sox after his Chicago squad had already won 91 games. Richards, who had lifted the traditionally cellar-dwelling South Siders out of the basement in his four years in the Windy City, was considered one of the top men in the game and a rising managerial star. They enticed him with the rare opportunity to serve as both general manager and field manager, building his own club from the ground up. The hypercompetitive Richards, a no-nonsense former catcher, could not resist the challenge of remaking the perennial worst franchise in the league (the former Browns) and put his baseball theories to the test. How badly did Richards like to win? He taught Sunday school at his Baptist church in the off-season and was known for cheating at golf and having “the foulest mouth in the major leagues,” according to one umpire.

Although they fought like hell, Richards kept the similarly sharp and strong-willed farm director he inherited, Jim McLaughlin, whose efforts had gone for naught with the financially strapped Browns. McLaughlin’s top scout, Jim Russo, remained in place as well. (Russo stayed with the O’s until 1986). Adamant about getting at least two sets of eyes on every potential signee, McLaughlin is often credited with creating the first holistic system for appraising talent—a Moneyball mind decades before Moneyball, in other words. To his credit, McLaughlin, like Richards, also knew front office and managerial talent when he saw it. He hired future director of player personnel Harry Dalton, today a member of the Orioles Hall of Fame, just before the start of the ’54 season.

Richards believed in pitching and defense, teaching the same “don’t beat yourself” fundamentals at every step of the Orioles farm system. He penned an influential book, Modern Baseball Strategy, a year after arriving in Baltimore and put together an instructional manual for the O’s minor league managers and coaches, which soon included Earl Weaver and Cal Ripken Sr. It’s no small coincidence that both Weaver and Cal Sr. started their minor league tenures with the organization, Earl as a manager and Cal Sr. as a catcher, in 1957. Richards’ working manual evolved into what became known as “The Oriole Way.” Eventually, the O’s early front office, scouting team, and coaches would sign and develop not just Brooks Robinson, but Boog Powell, Dave McNally, Jim Palmer, Andy Etchebarren, Mark Belanger, Davey Johnson, Eddie Watt, and Tom Phoebus, among others, all members of both the 1966 and 1970 World Series championship clubs.

It had taken six years for Richards to put a winning team on the field, but once they got there, the O’s only suffered two losing seasons (’62 and ’67) until 1986. The youthful 1960 “Baby Birds” challenged the Yankees for the pennant into mid-September and earned Richards manager-of-the-year honors. That club, cementing Baltimore’s love affair with the still-new Orioles, starred young pitchers Chuck Estrada, Milt Pappas, Steve Barber, and Jack Fischer, all of whom won at least 10 games and were just 21 or 22 years old, and sluggers Jim Gentile and Gus Triandos. When Gus moved his family into a new development in Timonium in 1962, they named a street after the three-time All-Star—Triandos Drive.

The same year the Birds broke through, the then-23-year-old Robinson came into his own, making his first All-Star team and winning the first of his 16 Gold Gloves. He finished third in the MVP voting, behind guys named Roger Maris and Mickey Mantle.

“Oh, we had a good club, a bunch of us, pitchers Chuck Estrada and Wes Stock, shortstop Ronnie Hansen, who is still a good friend, second baseman Marv Breeding, we’d all played together in Vancouver in 1959,” recalls Robinson. “We gave the Yankees all they could handle. I think we snuck up on people that year.”

“Of course,” the 83-year-old Hall-of-Famer adds, noting the Birds remained a contender in ’63, ’64, and ’65, “we didn’t get over the hump until we got Frank.”

In what remains one the most lopsided baseball trades ever, new director of player personnel Harry Dalton pulled the trigger on a deal before the 1966 season that had been in the works for weeks. Dalton and the O’s sent Pappas plus reliever Jack Baldschun and an outfield prospect named Dick Simpson to the Cincinnati Reds in exchange for their former National League MVP Frank Robinson, infamously described afterward as “an old 30” by Reds owner Bill DeWitt.

In his 19th game, Frank Robinson hit the only home run ever out of Memorial Stadium, sending a message that he was far from over-the-hill. He went on in ’66 to capture the Triple Crown, lead the O’s to the World Series title, and earn AL MVP honors—still the only player to win that award in both leagues. “Frank was the best player I ever played with, an unbelievable competitor, and he became a lifelong friend,” Robinson says of his fellow Hallof- Famer, who passed away in 2019. “Our wives became good friends. On the road, we’d check to see where each other was going for dinner after the game, and I know that helped bring the team together. We were like a family in those days. There wasn’t anything I wouldn’t do for him or that he wouldn’t do for me.”

There is one other link between the 1954 O’s and that great team with Brooks and Frank, which made three straight trips to the World Series and was described on the April 1971 cover of Sports Illustrated as “The Best Damn Team in Baseball.” And that’s Billy Hunter. Middle-aged and older Birds fans will likely recall the colorful Hunter as a longtime third-base coach, first for Hank Bauer and then for Earl Weaver. His tour of duty waving runners home lasted from 1963 to 1977, when he left to manage the Texas Rangers. No team in baseball had a better record during that stretch than the Orioles.

Hunter had been the O’s starting shortstop in 1954 before he, too, was traded to New York. Hunter, however, used his Yankees’ World Series money the next year to put a down payment on a house in Cockeysville. The 92-year-old Hunter still lives in that same home. Bauer, his former Yankees teammate, asked him to join him in Baltimore when he took over as manager in ’63.

What was the difference between Bauer and Weaver? “Weaver was ready, always ready for a scrap,” says Hunter, who took over managing duties multiple times every year following the combustible Weaver’s inevitable ejections. “Bauer was a born scrapper, too, he just hid it better. They both really wanted to win. That’s what they had in common. We all did.”

To ease the tensions during the season, it was Hunter who convinced a reluctant Frank Robinson to serve as “judge” in the O’s legendary, post-game Kangaroo Court. “The idea was, loosen everybody up and point out mistakes at the same time,” he says. “It was a good way, in a lighter atmosphere, to get a point across about a missed sign or someone throwing to the wrong base.”

With all the pennant-clinching games and World Series contests he ultimately participated in, there aren’t a lot of moments that stand out from the 100-loss ’54 season, Hunter admits. But there is one that remains indelible.

“When we got to Camden Station from Detroit—and how about that, where they play now—we arrived in our new home uniforms,” says Hunter, 67 years later, recalling the details as if it happened yesterday. “We got into the convertibles and made the trip from downtown to Memorial Stadium. I don’t know how long it took, but it was unbelievable. There were people everywhere, hanging out of the windows all the way, and I don’t know how deep on the sidewalk. I was in a car with Vern Stephens and Chico Garcia, throwing balls out to the crowd. It was like we had won the war or the World Series, and we hadn’t played a game yet in Baltimore. We couldn’t believe it. We were looking at each other and thinking, ‘What a difference from St. Louis.’”

ORIOLES 1954 BY THE NUMBERS

OPENING DAY PARADE: 350,000-500,000 fans line Charles Street

HOME OPENER APRIL 15: O’s win 3-1 before 46,354 fans

MOST GAMES OVER .500: 1

DAYS IN FIRST PLACE: 1

EJECTED: Manager Jimmy Dykes from both ends of June 6 doubleheader

TICKETS: Field Box—$3.00; Gen. Admission—$1.50; Bleachers—75¢

LONGEST GAME: 17 innings (8-7 win over Boston, June 23)

LONGEST WINNING STREAK: 5 games (June 23 - June 27)

LONGEST LOSING STREAK: 14 games (Aug. 11 - Aug. 25)

MOST RUNS SCORED: 10 (July 30 & Aug. 2, both wins)

MOST RUNS ALLOWED: 14 (April 14, May 23, & May 28, all losses)

WALK-OFF WINS: 9

WALK-OFF LOSSES: 13

TOP HITTER: Cal Abrams (.293 average)

TOP PITCHER: Bob Turley (14-15, 3.46 ERA)

RECORD: 54-100 (.351) 7th place

ATTENDANCE: O’s draw 1,060,910 fans to Memorial Stadium. Source: 1954 Orioles media guide