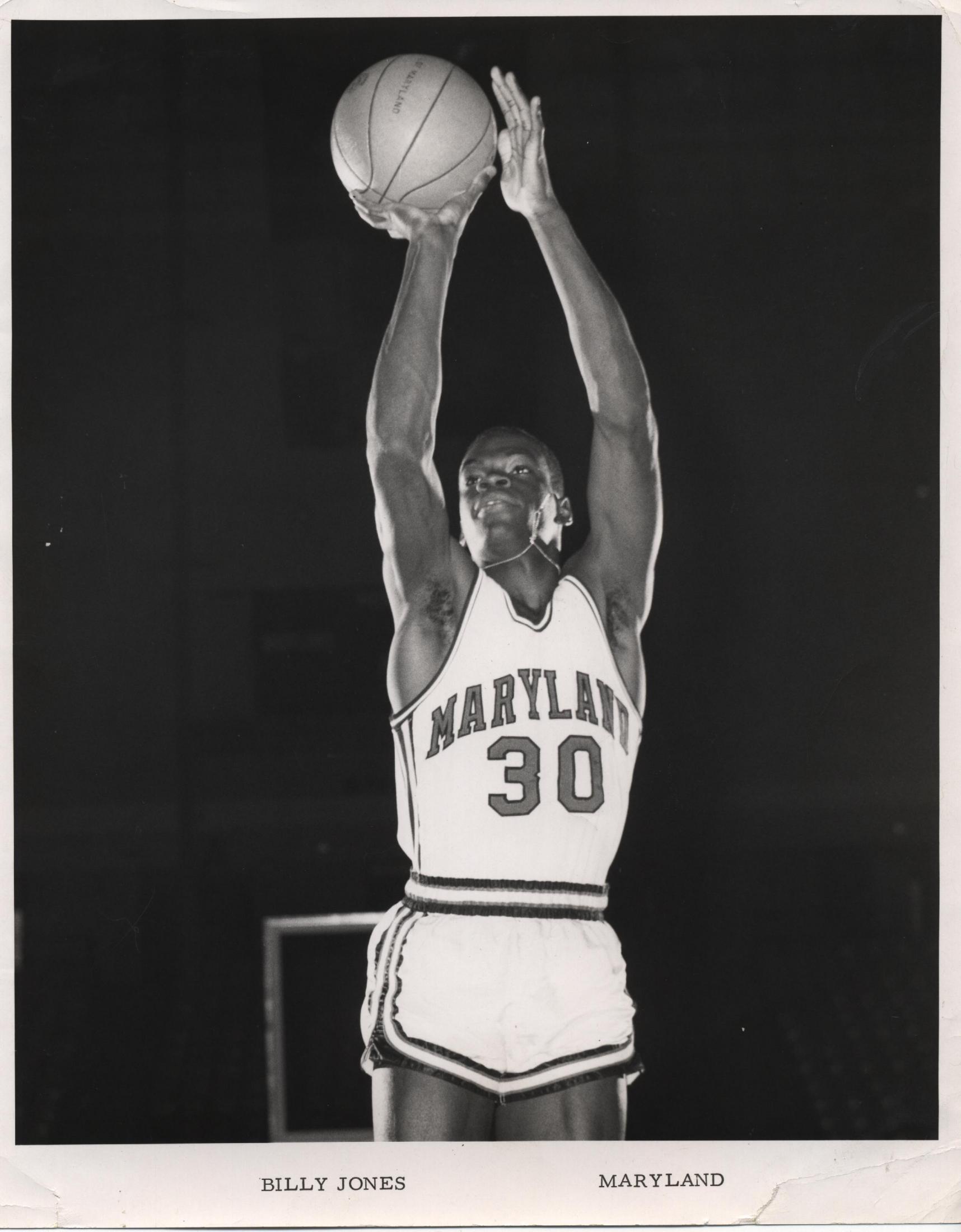

Darryl Hill can’t recall specific conversations he had with Billy Jones after the former Towson High basketball star followed him to the University of Maryland—where the two would become the first Black athletes to play for the Terps in their respective sports.

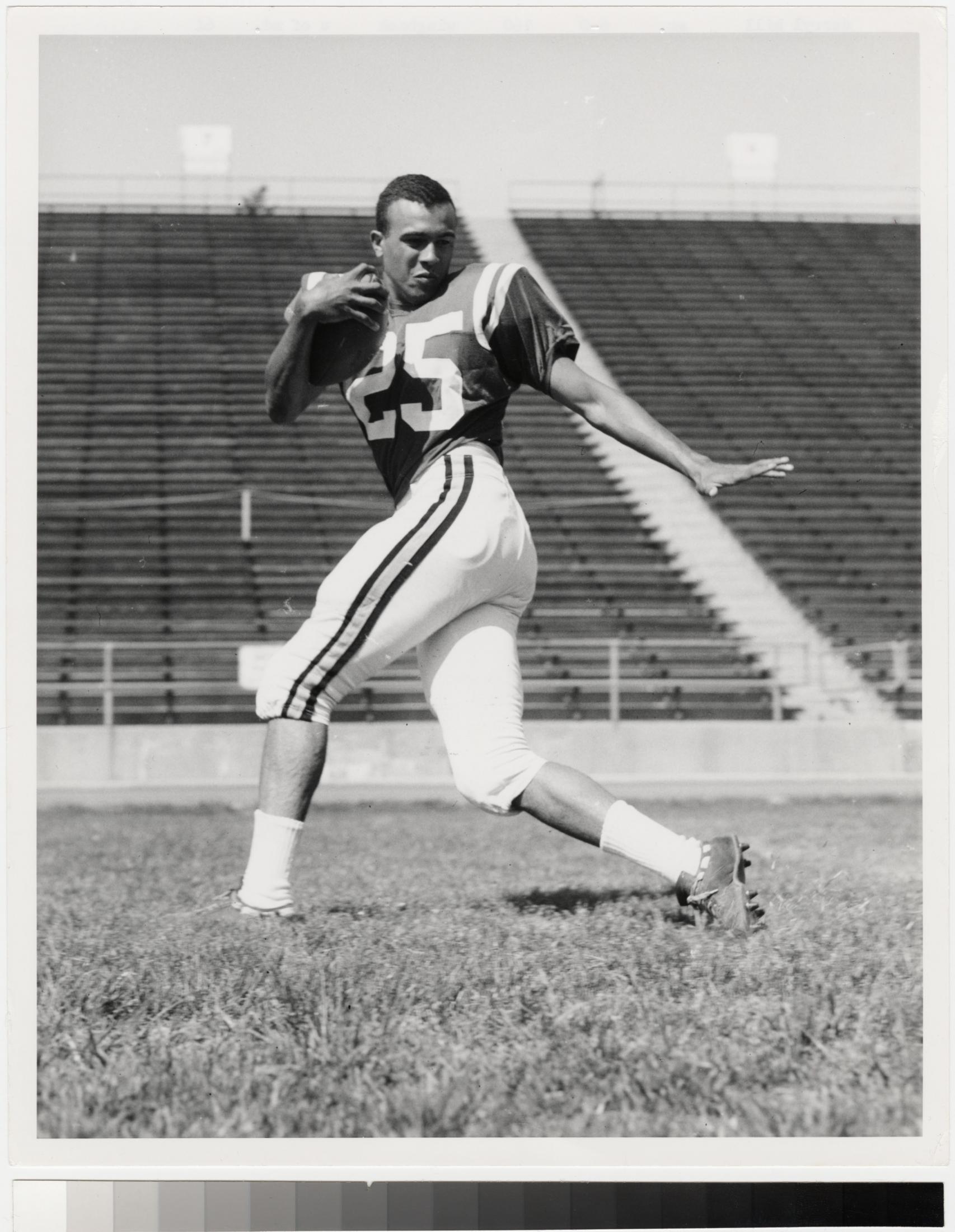

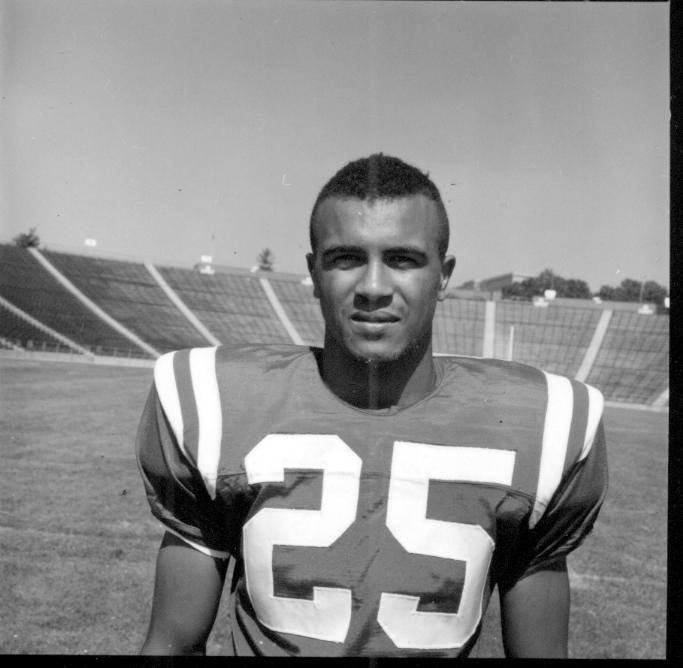

By the time Jones arrived in 1964, Hill was a senior who had not only broken the Atlantic Coast Conference’s (ACC) color line, but also set several school and league football records as a standout wide receiver and punt/kick returner.

Nearly 60 years later, Hill says he clearly had some advice for Jones and Pete Johnson, another Black player who came to the school at the same time as Jones but wound up redshirting as a sophomore and not officially starting his career until a year later.

It would serve them all well during their years in College Park.

“I’m sure I told them to keep their heads down, try to attract as little attention as possible,” Hill, 77, recalled last week.

Hill and Jones have long been linked to opening the door for Black athletes in the ACC. Now, there is an even more lasting connection between the two septuagenarians, with their surnames hyphenated on the recently completed Jones-Hill House—the new home for Maryland football.

“Billy said getting your name on a building is a more permanent recognition of your accomplishment,” Hill said at an unveiling of the new facility last week. “Papers, books, newspaper articles, even plaques and memorabilia, they can all disappear, but that building is going to be there no matter what. It’s a lasting memorial.”

While honoring Hill’s legacy had occasionally been mentioned as the facility was being built, the addition of Jones’ came as a surprise—even to Jones himself. He recalled getting on a Zoom call in April with university president Darryll Pines, athletic director Damon Evans, Under Armour founder and executive chairman Kevin Plank, and Hall of Fame coach Gary Williams—a former teammate and still a close friend.

“I thought this was a big alumni hit for the money,” Jones, 74, said with a laugh. “They’re coming with the big guns. They don’t want thousands, they want some serious numbers. When they laid it out for me, I was just dumbfounded. I was honored and humbled beyond belief, and just absolutely amazed they wanted to do this.”

The state-of-the-art facility, six years in the making at a cost of nearly $150 million, was built in stages. The first phase opened with an indoor football practice space that was constructed within the shell of Cole Field House—the iconic arena where the Terps played basketball from 1955 to 2002.

Speaking to the media after a walk-through of the entire facility Friday, Evans credited Hill and Jones for being “trailblazers” on the college level.

“When you talk about Billy Jones and Darryl Hill, what they went through, they set the standard for people such as myself and [third-year football coach] Mike Locksley,” Evans said, “and for a lot of our student-athletes to be able attend an institution such as the University of Maryland, as well as participate in intercollegiate athletics.”

Both Jones and Hill credit their respective upbringings for helping them adjust to college life and survive the treacherous journey for Black athletes in the South during the turbulent 1960s.

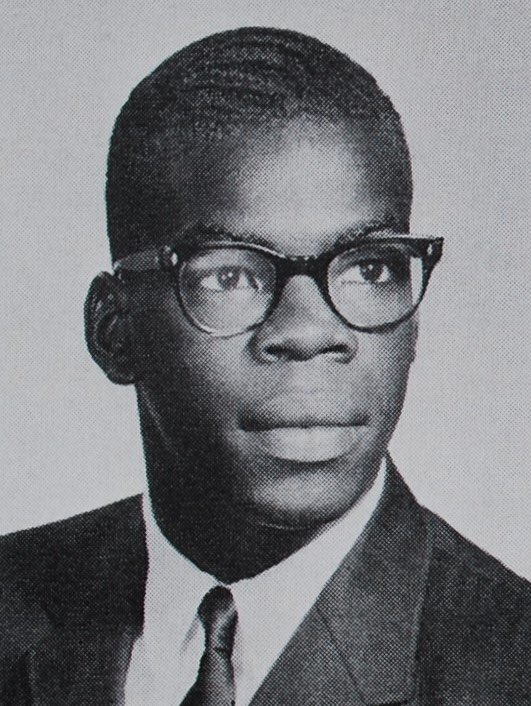

Jones said that his life in the predominantly Black enclave of East Towson gave him the athletic skills and strength of character to succeed both at a nearly all-white Towson High—which he led to a state title in 1963—and then in college, where he and Hill were among 250 Black students in an enrollment of around 13,000.

Hill’s experience as the first Black football player at his private Catholic high school in Washington, D.C., where he graduated two years ahead of his class, as well as at the Naval Academy, where he played a year before transferring, proved invaluable as a Terp.

And just as Hill has often thanked football teammate Jerry Fishman for helping shield him from the threats he faced, particularly when the team went on the road, Jones said that Williams and another teammate, Joe Harrington, went out of their way to make him feel comfortable as a freshman.

“Gary Williams and Joe Harrington were the first players to greet us,” Jones said. “They made sure we had rides, they looked out for us, they always made sure that I was squared away. Gary still has my back to this day.”

Given Maryland’s long affiliation as the northernmost school in the ACC, both players experienced their share of racism during their careers as Terps. Hill received death threats before he ever stepped on the field at Byrd Stadium. He saw the president of Clemson University intervene on behalf of his mother when she was denied entrance to the football stadium in Death Valley, having her sit in his private box during a game in which her son set an ACC record for receptions.

The most lasting memory for Jones happened before a game at South Carolina State University.

“The ball rolled into the stands during the warmup and it’s like two rows in, and I go and get it,” Jones recalled. “I lean over to pick up the ball and there’s a gentleman with a brown suit and a cigar. He whips the cigar out of his mouth, blows the smoke in the air and just looks me right in the face from about three feet away and says ‘[the N-word].’”

By Jones’ junior year, when Pete Johnson had joined the team, Jones said that Rich Drescher, an all-American discus thrower who also played basketball for the Terps, often served as their unofficial bodyguard on road trips through the South.

The six-foot-four, 235-pound Drescher had grown up in Cambridge, Maryland, a hotbed for racial unrest in the 1960s. “He was a man’s man,” Jones said. “He was a great travel partner, he quietly looked out for us. I don’t tell people enough about Rich Drescher.”

Jones had not been inside the indoor practice facility at Maryland when it first opened in 2017, and was impressed with the expanse of the building in its entirety when he and Hill went back and toured it as part of an event with donors last Friday.

“It is amazing,” said Jones, who was the head coach at UMBC from 1974 to 1986. “It is absolutely phenomenal.”

The new building includes a 24,000-square-foot strength and conditioning room that is four times the size of the space used in the previous Gossett Team House, which will now be turned into a center for academic support. There are 126 individual dressing stalls that feature a recliner and ottoman for each player, as well as an automatic charging station. The players’ lounge has a recording studio and a barber shop that can be converted into a DJ station.

Calling the completion of the project “Christmas in June,” Locksley hopes that the new football facility can help the Terps continue the progress they made on the field last season—an impressive road win at Penn State being the highlight of Locksley’s tenure to date—as well as in recruiting.

“Like I told our team earlier today, it isn’t that we hit the lottery and it’s time to lay back and enjoy the fruits of the lottery,” Locksley said. “This building shows excellence, which sets a standard. Our players have to understand that excellence is the standard. I like to say, ‘The best is ahead.’ We’re looking forward to being able to display the commitment that Damon, the university, and all of our supporters have made to us.”

While Evans credited Plank, whose $25-million donation kickstarted the fundraising, as well as longtime athletic donor Barry Gossett, Locksley made sure to thank three men who had passed away after helping the project get to the finish line.

He expressed his gratitude to Maryland State Senate president Thomas V. ‘Mike’ Miller, who passed away in January, as well as donors Mark Butler and Rich Novak, also a former Terp quarterback. Butler, who died in December of 2019, has his name attached to the tunnel that will take the team from the facility to the field at Maryland Stadium. Novak, who died in March, has his and his widow’s name on the locker room.

For Jones’ part, he also doesn’t want to see Pete Johnson’s name forgotten in telling the history of Maryland athletics. Johnson passed away in 2015, a year before ground was broken on what is now known as the Hill-Jones House.

“You can’t tell my story without telling Pete’s story,” Jones said.

Meet the Author: Don Markus covered sports for the Baltimore Sun for 35 years, including nearly two decades focusing on University of Maryland athletics.