Style & Shopping

We’ll Always Have Paris West: Meet the Crew Behind the Enduring Eyeglass Shop

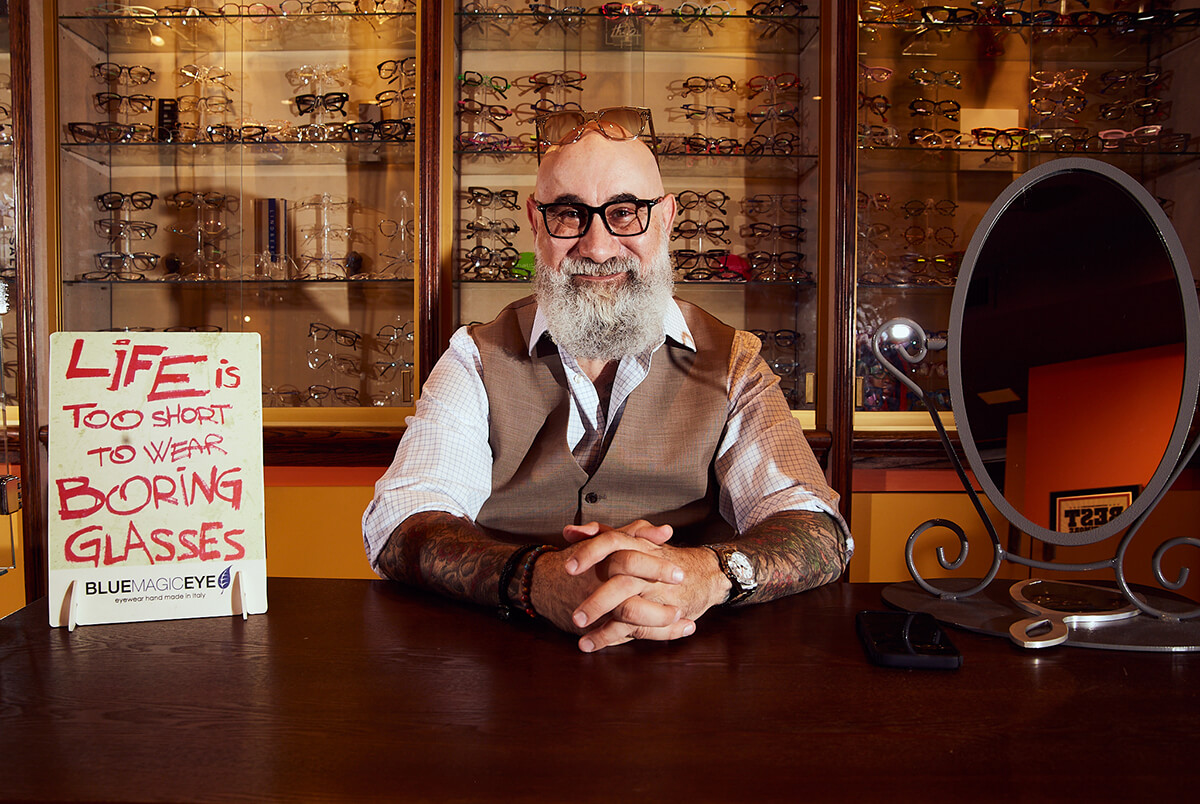

For owner Jordan Flitter, it’s been a spec-tacular 28 years in business.

You expect a laugh track to be playing when you walk through the glass doors of Paris West Optical in the heart of Mt. Vernon. It has an endearing Everybody Loves Raymond vibe, with owner Jordan Flitter, 53, playing the role of Ray, a sweet curmudgeon who bellyaches about his family while simultaneously basking in the glow of their presence. Mom Harrelyn Rosenthal and brother Lance Flitter both work with Flitter, along with a sitcom-worthy cast of characters including a childhood best friend.

It’s easy to see why his staff and customers are drawn to him. He tells it like it is and has created an expansive career on the premise of honesty and hard work. What’s more, the man loves glasses. He can’t get enough of them. He geeks out over a brilliantly crafted pair of spectacles the way some guys react to high-end cars or the latest tech gadget. Glasses aren’t just his business, they’re his passion—and he passes that passion along to his customers.

Not bad for a kid who dropped out of high school. Flitter grew up poor in Delaware County, Pennsylvania, a suburb of Philadelphia. “We had government cheese and the blue card to get free lunches,” he says.

He left school in 11th grade and started working for a telemarketing firm—making $500 a week. He liked having money, but his mom was heartbroken. To appease her, Flitter said he would return to school but only in the work studies program, which allowed him to continue working while simultaneously earning enough credits to graduate. “Long story short, I kept the same job…until the FBI shut it down,” he says with a straight face. That’s how most of Flitter’s stories go—almost unbelievable tales that propel him onward to the next adventure. He never derails, just switches to a different set of tracks.

To stay in the work studies program, he’d have to find another job. “Pick something off the board,” the program coordinator told him. He saw “apprentice optician,” and pointed at it. “What’s an optician?” he asked. He was told, “They make eyeglasses.” His next question: “What’s the pay?” And that was that—an almost three-decade career was born. “I didn’t wear glasses,” laughs Flitter. “I didn’t do sunglasses.”

But soon he was learning the craft at the spectacle mothership—LensCrafters. When a co-worker left for a smaller shop—“No nights, no weekends, and better pay,” he boasted—Flitter was instantly jealous. He’d always dreamt of that kind of independence. He left LensCrafters for a job with a small, independent optician. When the optician retired, he gave Flitter a great reference and he was quickly hired at a high-end eyewear boutique in Philadelphia. That gig worked out so well that Flitter bought the business—but it wasn’t quite as legit as he hoped. (“The guy I ended up buying the store from was having an affair with his office manager. He wanted to hide the assets from his divorce.”) Reminder: Never a dull moment with this guy. He bought a second business from the same man, but something just didn’t feel right, so Flitter opened up a third location on his own.

Not all the businesses worked out. A shopping center went bankrupt, so the store he had there closed. Next, a friend who was working for him embezzled money from another location and Flitter was forced to liquidate. (He did save the cabinets, which are still in use at Paris West.) Then there was another incident, says Flitter, where the original owner (the one having the affair) showed up and took back his merchandise at gunpoint. (See?!)

In the midst of all that, Flitter was in and out of the hospital—he was later diagnosed with non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma, a type of blood cancer. He was barely 23 years old. The Phillies went to the World Series that year and Flitter spent a lot of time watching baseball games from a hospital room.

“I didn’t feel bad for myself. I was just angry,” he says. “Anger is a good motivator.”

He knew it was time to get out of Philadelphia. Baltimore was on his radar because of the hospitals—“I always associated Johns Hopkins with cancer-curing”—and because of his mother’s uncle, who lived in Pikesville and had always acted as a mentor to him. Flitter figured he’d move to Baltimore and become an optometrist. But his great-uncle convinced him that wasn’t necessary. He should keep doing what he did best—running a full-service luxury optical boutique—and hire an optometrist as his employee.

Flitter ended up taking a space on Charles Street—across from the Baltimore Basilica—that had been home to Bowen & King. “The fact that it was an optical shop prior seemed like divine intervention,” he says. He signed a three-year lease and opened in June 1995. “We’re here longer than the Ravens,” jokes Flitter, a line he’s surely used before—but a fact he’s justifiably proud of.

He already had the name picked out. “I wanted a name that wasn’t generic and implied high fashion,” says Flitter. He narrowed it down to Milan West or Paris West—names that evoked two glamorous cities where many of their exclusive frames originated. “But Paris West rolled off the tongue better.”

He made that decision when he was 18—seven years before he opened his first Baltimore store. “I always knew I wanted to be self-employed.” Even as an eight-year-old, when most kids can’t even say the word “entrepreneur,” he dreamt of being one. “My dad was an entrepreneur too,” says Flitter. To him that meant never answering to anyone but himself. It also meant a lot of learning on the job and not always doing things the “right way.”

“I WANTED A NAME THAT WASN’T GENERIC AND IMPLIED HIGH FASHION…”

Paris West has a quirky, artsy vibe that reflects the sensibilities of its owner. The walls are pumpkin orange and mustard yellow. There’s abstract art painted by a customer behind a giant orange faux-marble counter that always has a bowl of Jolly Ranchers. The glass cases line every wall, and the frames are displayed like delectable pastries—you don’t know which one to try first. From the outside, the huge windows—with the familiar logo—promise “exotic eyewear” and “The Joy of Spex,” a definite nod to Flitter’s sense of humor.

He doesn’t fit into a mold, and that seems to be what makes him so popular. Again, he doesn’t just sell glasses—he’s obsessed with them.

“You’re supposed to turn over your inventory three to four times a year,” he says. “Mine turns, but it’s measured in decades not years.”

That might be because he has somewhere around 8,000 frames in the store. (“And the ones in your garage,” his mother reminds him.) It started as a way to differentiate himself from other shops. He wanted even the most discerning, picky customer to come in and say, “Wow, I can find glasses here.” And they do. As one customer leaves with her tween, Flitter says, “She started coming here when she was single.” Another has bought 40 pairs of frames from him.

In 2006 he moved from 403 N. Charles Street to his current location at 521 N. Charles Street, a block from the Washington Monument, because he and his landlord didn’t get along. (Flitter recounts their rift in much more colorful language.) It’s been 17 years in his “new” space and he just signed a 10-year extension, starting next year.

Flitter is flanked by his mother and brother almost the entire interview. They nod, and interject a few times, but mostly they listen. Lance, who has his own frame line, Leap Eyewear, pops up to answer the phone and help customers. Flitter, his arms covered in tattoos and a big bushy beard enveloping his friendly face, is the king of the gentle jabs—especially with his mother.

“I don’t get paid,” she mentions. (Though she is sporting a beautiful new pair of frames—on the house, naturally.) “I just hang out here.” I know, Flitter ribs, “I never hired you.” She and Lance come down every Friday and Saturday from Philadelphia. Her job seems to simply be mom—lovingly intrusive and supportive to her sons and the customers. (More on that later.)

It’s that familial atmosphere that has made the store so irreplaceable to Flitter. “I almost sold,” he admits. “I was offered over a million dollars by a private equity company to sell.” Mom Harrelyn, acting like a Greek chorus, pipes in, “Why didn’t you sell?”—even though she knows the answer. “Well, they would’ve required me to work for them for three years,” Flitter explains. And they both start laughing. They know Flitter would never work for anyone. Plus, he says, “My mother said I’ll be bored if I retired.”

That’s not really true. He’s tired a lot of days. Though he’s been cancer-free since 2010, he’s also battling an autoimmune disease. But he feels a sense of responsibility to the people who work for him. “I hate to think my whole identity is this place, because that would be sad,” says Flitter. “But I try to take care of my family and my friends—it’s half the reason I’m doing this now.”

The other half is the customers. A handsome patron walks in holding two pairs of high-end glasses that need adjustments. “My mom has a crush on you,” Flitter tells him as Harrelyn shushes him while laughing.

Flitter knows every customer, every pair of glasses they’ve ever bought from him, and probably what their next pair should be. When the customer leaves 15 minutes later, after some sweet flirty banter with Harrelyn, Flitter points out that he has left almost $1,400 worth of glasses at the shop without any sort of receipt. The customers trust him.

FLITTER KNOWS EVERY CUSTOMER, EVERY PAIR OF GLASSES THEY’VE EVER BOUGHT FROM HIM, AND PROBABLY WHAT THEIR NEXT PAIR SHOULD BE.

“I’ve had to ‘fire’ three customers,” Flitter cracks. “Two apologized and I took them back. One guy never came back, but he also threatened to kill me.” There’s barely time to process that story when he’s on to the next: “I was supposed to meet my customer Karen last week, but I stabbed myself in the foot…” (It was a dropped box cutter that sliced his foot, and he ended up with three stitches. He’s fine.)

Karen is a customer from his Bel Air location, which opened in 2013. He assumed ownership from optician Bruce Linder before he passed away of cancer. Linder’s shop on Main Street had been a fixture for 37 years and, knowing how sick he was, he wanted to be assured that his customers were in good hands. It took some convincing from Linder, but over a five-hour lunch—“we both like to talk”—Flitter felt like the two were kindred spirits and eventually agreed to the purchase.

So, now it’s been 10 years of running two stores—through a pandemic, through the rise of discount eyewear brand Warby Parker, through two burglaries. And Paris West perseveres.

“We’re at this weird place where there’s less and less small businesses and less and less personalized service,” observes Flitter. “There’s less artisans and a lot of mass-produced commoditized things.”

Yet, 90 percent of what he sells are lines that people haven’t heard of before. These companies are Flitter’s favorite—the small-batch, independently-owned brands that have been in business for a century.

After a few lean years Flitter wasn’t sure if that mattered to his customers. But then people started coming back. “They’re dropping off their Warby Parker glasses to donate, and we were getting more referrals and we started getting more young people,” he says. And he noticed it was the “young people” who appreciated the selection but especially the customer service. “If you buy something from a big chain, you’re never going to talk to the owner, much less the CEO of the company,” he notes. And yet here was a CEO who remembered everything about them—including their prescription strength.

But regardless of all that, Flitter spends a lot of time talking with his therapist about imposter syndrome. “I feel like I shouldn’t be doing this. I shouldn’t be running a business,” he says. Sometimes he focuses on what he didn’t do instead of everything he did. “I’m not a doctor. I’m not even officially trained. I just learned on the job as an apprentice. I didn’t go to school.”

All around him activity is happening at Paris West. The phone is ringing, orders are being processed, a customer is looking at frames. Despite his self-doubt, the shop is doing exactly what it should.

“I always have this fear that things are going to end,” Flitter says, “but that probably just keeps me moving.”