Birds are disappearing across Maryland—and North America. But citizens and scientists on the ground offer room for hope.

ust before dawn on one of the last days of winter, the houses are still dark and the roads mostly empty as the first peach light begins to break along the horizon of Maryland’s Eastern Shore. In fact, the moon seems to be the only one out here, riding high above switchgrass fields and silhouette tree lines. That is until you reach the end of a long dirt lane and step outside of your car to listen. The sound comes from every angle and consumes the senses—trills and tweets, warbles and whistles—the invisible chorus of birdsong, rising with the morning sun.

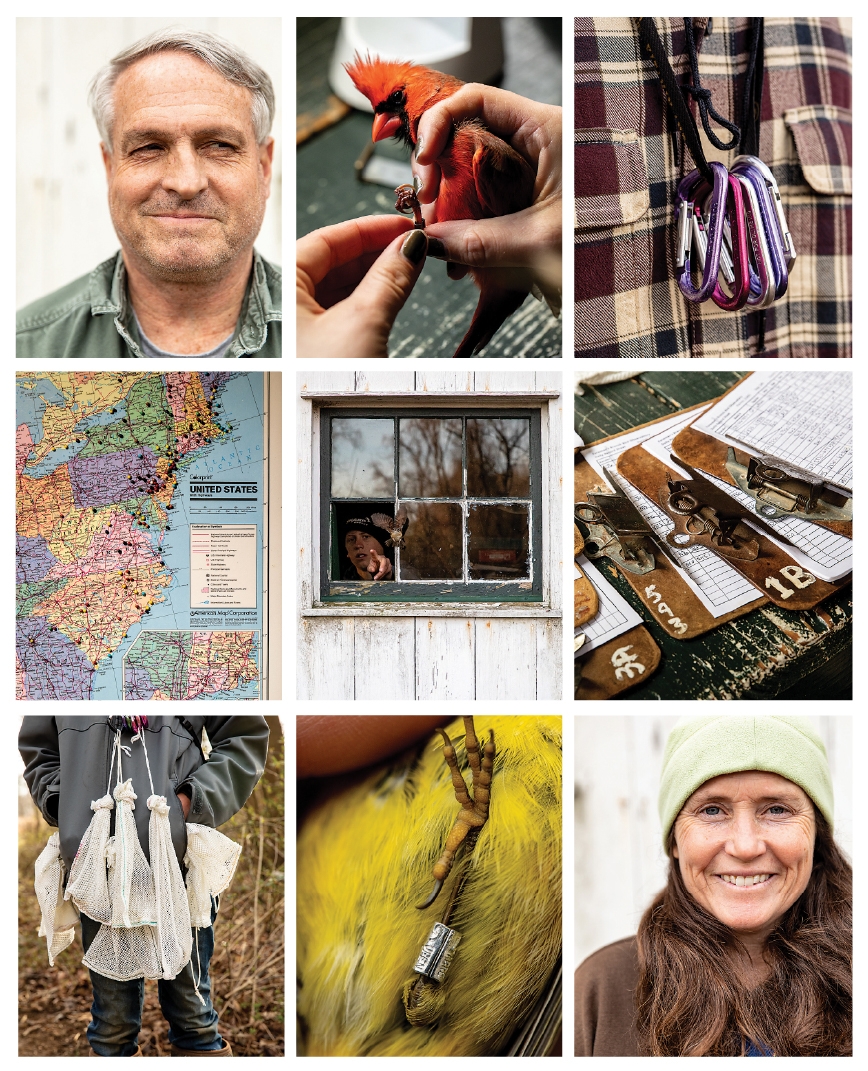

Before long, there is also the crunch of muck boots on fallen leaves as Jim Gruber trudges uphill from behind the old Foreman’s Branch field office, a half-dozen bulging mesh bags dangling from his hips. He heads inside into a small square room, walls covered in curling maps and stacked ceiling high with faded guidebooks, then hangs each fluttering specimen like an ornament from the exposed rafters.

Gruber, director of this Washington College operation in rural Chestertown, along with resident field ecologist Maren Gimpel and their three students interns, are soon seated at a long table, reaching their hands into the bags and gently pulling out live birds—cardinals, sparrows, a tufted titmouse—all surprisingly calm, nestled between their middle and forefingers. Under the glow of desk lamps, they fasten a tiny metal band stamped with nine digits to each of the birds’ even tinier ankles, determine age and sex, and measure wing length and weight before opening a small windowpane and releasing them back into the open air.

Fear not, they fly off, completely unphased by this alien abduction.

“This is a white-throated sparrow,” says Gimpel, holding a brownish bird with a yellow forehead. “They’re only here in winter, and their song is a really nice clear whistle: ‘Old-sam, pea-body, pea-body, pea-body,’” and off it goes.

At least once an hour, the team treks out across this sprawling countryside, through the woods and along the field edges, toward a labyrinth of some 90 nylon nets that catch these birds in their loose pockets. From March through May, they’ll band everything from hawks to hummingbirds, then return again come autumn, marking some 15,000 birds a year. At the end of the season, their records will be reported to the federal government and stored for science, much as they have been since the observatory began in the late 1990s.

But over those years, there have also been changes.

“Myrtle warblers are way down, whip-poor-wills are gone,” says Gruber, running down a mental list. “You used to go out in the summer evenings and hear them calling near Tolchester Beach.”

“We’ve all inevitably heard an older birder say, ‘In my day, there used to be…,’” adds Gimpel. “Those stories sound crazy to us now.”

For this crew, the disappearances are concerning, but the importance of their work is not about yesterday, or tomorrow, when they’ll do it all over again. They want to know, like many others: What will things look like in the next 100 years, or 50, or 20?

And they're not the only ones who want to know.

“This is a white-throated sparrow. They’re only here in winter, and their song is a really nice clear whistle: ‘Old-sam, pea-body, pea-body, pea-body.’”

top row, from left: Jim Gruber, banding director; a band is applied to a cardinal's leg; carabiners for carrying mesh bags. middle row, from left: a map depicting later sightings of Foreman's banded birds; intern Jonathan Irons releases a Carolina wren; data sheets. Bottom row, from left: bagged birds; a banded palm warbler; field ecologist Maren Gimpel.

top row, from left: Jim Gruber, banding director; a band is applied to a cardinal's leg; carabiners for carrying mesh bags. middle row, from left: a map depicting later sightings of Foreman's banded birds; intern Jonathan Irons releases a Carolina wren; data sheets. Bottom row, from left: bagged birds; a banded palm warbler; field ecologist Maren Gimpel.

top row, from left: Jim Gruber, banding director; a band is applied to a cardinal's leg; carabiners for carrying mesh bags. middle row, from left: a map depicting later sightings of Foreman's banded birds; intern Jonathan Irons releases a Carolina wren; data sheets. Bottom row, from left: bagged birds; a banded palm warbler; field ecologist Maren Gimpel.

top row, from left: Jim Gruber, banding director; a band is applied to a cardinal's leg; carabiners for carrying mesh bags. middle row, from left: a map depicting later sightings of Foreman's banded birds; intern Jonathan Irons releases a Carolina wren; data sheets. Bottom row, from left: bagged birds; a banded palm warbler; field ecologist Maren Gimpel. It’s not every day that ornithology makes national headlines, but last fall, the prestigious academic journal Science released a report that sent shockwaves throughout the birding community, and beyond. In the last 50 years, it said, North American bird populations have plummeted by nearly 30 percent, with a staggering 2.9 billion birds lost since 1970.

“Bye-bye, birdie,” wrote Reuters. “The skies are emptying out,” said The New York Times.

While experts have long known that certain birds were diminishing, this ambitious study, led by researchers from a panoply of universities, government agencies, and nonprofits, revealed widespread loss. Across 529 species, a few populations improved, but the majority declined, often sharply.

“It’s not just these highly threatened birds,” said lead author Kenneth V. Rosenberg of Cornell University to the Times. “It’s across the board,” including traditionally abundant common birds like robins, cardinals, and blackbirds. A quarter of all blue jays and almost half of all Baltimore orioles have vanished.

And these losses likely have ominous implications beyond just bird populations—the proverbial canary in the coal mine. “Birds are a really important ecological link: they disperse seeds, they control insects, they can act as pollinators,” says David Curson, conservation director at the National Audubon Society’s Maryland-D.C. chapter. “Because they’re so visible and audible, making them easy to count compared to other animals, they’re important indicators of the wellbeing of our natural ecosystems.”

“If you take away one species, you might not notice the difference,” adds Gabriel Foley, coordinator for the region’s Breeding Bird Atlas survey, a five-year collaboration between the Department of Natural Resources, the Maryland Ornithological Society, the Maryland Bird Conservation Partnership, and the Cornell Lab of Ornithology to study local populations. “But as you remove more and more, things start to fall apart, like a Jenga tower. Something somewhere is wrong if you see massive declines like a third of your overall bird population gone over just a few decades.”

A cardinal wing.

A cardinal wing.

A cardinal wing.

A cardinal wing.Much of what was reported in the Science paper would not have been possible without the Patuxent Wildlife Research Center, located just down I-95 in Laurel and run by the U.S. Geological Survey on the same Fish & Wildlife Service refuge where famed conservationist Rachel Carson worked before writing her prophetic Silent Spring.

Here, Keith Pardieck now oversees the North American Breeding Bird Survey, which provided a bulk of the report’s data. One of the primary ways we understand the populations and trends of this continent’s birds, the survey takes place each breeding season, mostly throughout the month of June, when hordes of skilled birders set out on some 3,000 routes, including 54 in Maryland, each comprised of 50 roadside stops with rigorous protocols for counting every bird they see or hear. The data is then analyzed by the likes of veteran biologist John Sauer, who co-authored the Science piece, and released to the public, with records dating back to its inception in the 1960s.

“We can tell which direction the populations are going: are they increasing, are they decreasing?” says Pardieck. “It serves as any early warning system.”

And until last year, “We knew that populations were trending downward, but we didn’t have a scientifically defensible way to identify actual numbers,” says John French, Patuxent’s director. “And the numbers were big. They were rather shocking. These are significant declines.”

But where are the birds going? And why? The answers, in many ways, come down to us.

While Maryland’s natural diversity is one of the small state’s greatest strengths, from the dense woods of the Appalachian Mountains to the sandy shores of the Atlantic Coast, its human population has more than doubled since 1950, leading to habitat loss and fragmentation throughout wetlands, grasslands, and forest. Between 2010 and 2017 alone, Anne Arundel County lost nearly 3,000 acres of trees.

“People have to live somewhere,” says the Atlas’ Foley. “But for every development that goes in, there’s now another woodlot or meadow that’s been lost, and you don’t really get those back.”

For that, the Audubon Society has designated 43 “Important Bird Areas” across the state, or more than one million acres of essential habitat, including the grounds of Foreman’s Branch, as well as the Patapsco Valley and Prettyboy Reservoir in Baltimore County. But cities also play a vital role.

“Baltimore is an important stopover for migratory birds,” says Audubon’s Curson. “They can seek shelter and refuel at places like Patterson Park, where sometimes in early May, it can sound just like the Canadian forest.”

At the same time, urban areas can also look like ornithological crime scenes. “Four months out of the year, we walk about 25 buildings downtown and find at least 300 dead birds,” says Lindsey Jacks of Lights Out Baltimore, a nonprofit aimed at promoting bird-safe buildings, with collisions being a leading cause of avian mortality after outdoor cats (which, yes, really, account for as many as 3.7 billion annual deaths nationwide). “If you think about the rest of the city, then multiply that by the rest of Maryland, you can start to see how a billion birds are impacted in the U.S. alone each year.”

An early morning walk.

An early morning walk.

An early morning walk.

An early morning walk.Homes and low-rise buildings are the biggest offenders, she says, particularly those with windows across from greenspaces, as birds primarily collide with the reflected tree line. Injured birds are taken to the county’s Phoenix Wildlife Center for rehabilitation, while the dead ones go to the Smithsonian National Museum of Natural History collections or Johns Hopkins University’s School of Medicine for cancer and aging research. Lights Out also works with local businesses, like the National Aquarium, to mitigate exteriors with films and netting, or to turn lights off at night during periods of migration, so as to not confuse birds that navigate by starlight. Though statewide legislation to mandate bird-friendly government buildings stalled in the General Assembly this spring, it seems likely to pass next year.

But even out in the country, trouble remains, as modern agriculture and its intensive farming practices have greatly reduced hedgerow habitat for species like bobwhite quail, while also increasing pesticide use, which diminishes their food source, and worse.

“Remember years ago, when you’d drive down a country road at night and have bug splatter all over your windshield,” poses Robin Todd, head of the Maryland Ornithological Society, which maintains 2,264 acres of wildlife sanctuaries across the state. Insect populations are on the downturn, too, and as a result, “Aerial insectivores—swallows, swifts, nightjars, flycatchers, who catch food on the wing—are suffering real declines.”

“Common nighthawks used to fly around in the floodlights at sports arenas like Camden Yards, but it’s really unusual to see them now,” says Audubon’s Curson. “I think they’re telling us something.”

In mid-March, Maryland banned chlorpyrifos, a pesticide linked to developmental issues in children, as well as the likes of disorientation and death in birds, though Governor Hogan ultimately vetoed the measure. Last summer, the Environmental Protection Agency also backed out of its nationwide ban, seen by many as a victory for chemical companies.

And while 12 neonicotinoid-containing products were prohibited by the EPA last spring, dozens remain on the market, in everything from sprays to seed coatings, that also harm beneficial insects like bees, while impairing the cognitive abilities and appetites of birds.

Looking toward the future, though, it seems the most imminent threat might be that of climate change. Two-thirds of North American bird species are at increasing risk of extinction from global warming this century if current trends continue, according to a new Audubon study using data from Patuxent’s BBS and the United Nations’ Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, among others.

Extreme weather events, such as heat waves and the heavy rains that historically ravaged Ellicott City, could threaten their ecological balance. With rising temperatures, millions of birds are now migrating earlier, and “we’re concerned that delicate timing could be thrown out of kilter,” says Todd, noting the important synchronization of migration and nesting timelines with those of insect hatches.

Experts expect that many creatures, from butterflies to fish and particularly birds, will also shift their ranges northward. “We’ve been seeing this already,” says Patuxent’s French. “But whether they expand northward, or contract from the south, and if their current conditions are actually found elsewhere, that still needs to be explored.”

Other birds will be there, too, of course, fighting for the same food and habitat.

From left: cardinal; white-throated sparrow; palm warbler; tufted titmouse.

From left: cardinal; white-throated sparrow; palm warbler; tufted titmouse.

From left: cardinal; white-throated sparrow; palm warbler; tufted titmouse.

From left: cardinal; white-throated sparrow; palm warbler; tufted titmouse.Forest and coastal birds are most at risk in Maryland, according to the Audubon study, though many species are still vulnerable, including the Baltimore oriole. Local numbers remain largely consistent, but nearly 20 percent of their range could be lost during worst-case temperature increases. Meanwhile, the American woodcock and red-headed woodpecker would lose nearly all of their regional ground, while common birds, like house wrens and goldfinches, could be pushed entirely out of the state.

“It’s a call to action,” says Curson, noting the study’s findings that lower temperature increases will endanger far fewer birds.

His team is prioritizing the state’s tidal marshes and coastal bays in Dorchester and Worcester counties, which are highly vulnerable to sea-level rise. “Climate change poses an existential threat to these ecosystems and the birds that live in them,” he says, pointing to specialist species like the saltmarsh sparrow, which nests on the very edge of that sinking shoreline. With the Fish & Wildlife Service, they’re looking at ways to save the low-lying landscape, such as rebuilding parts of the Blackwater National Wildlife Refuge with native grasses and sediment dredged from the bay’s shipping channels, all in order to save the birds.

“You have to remain an optimist,” says Curson.

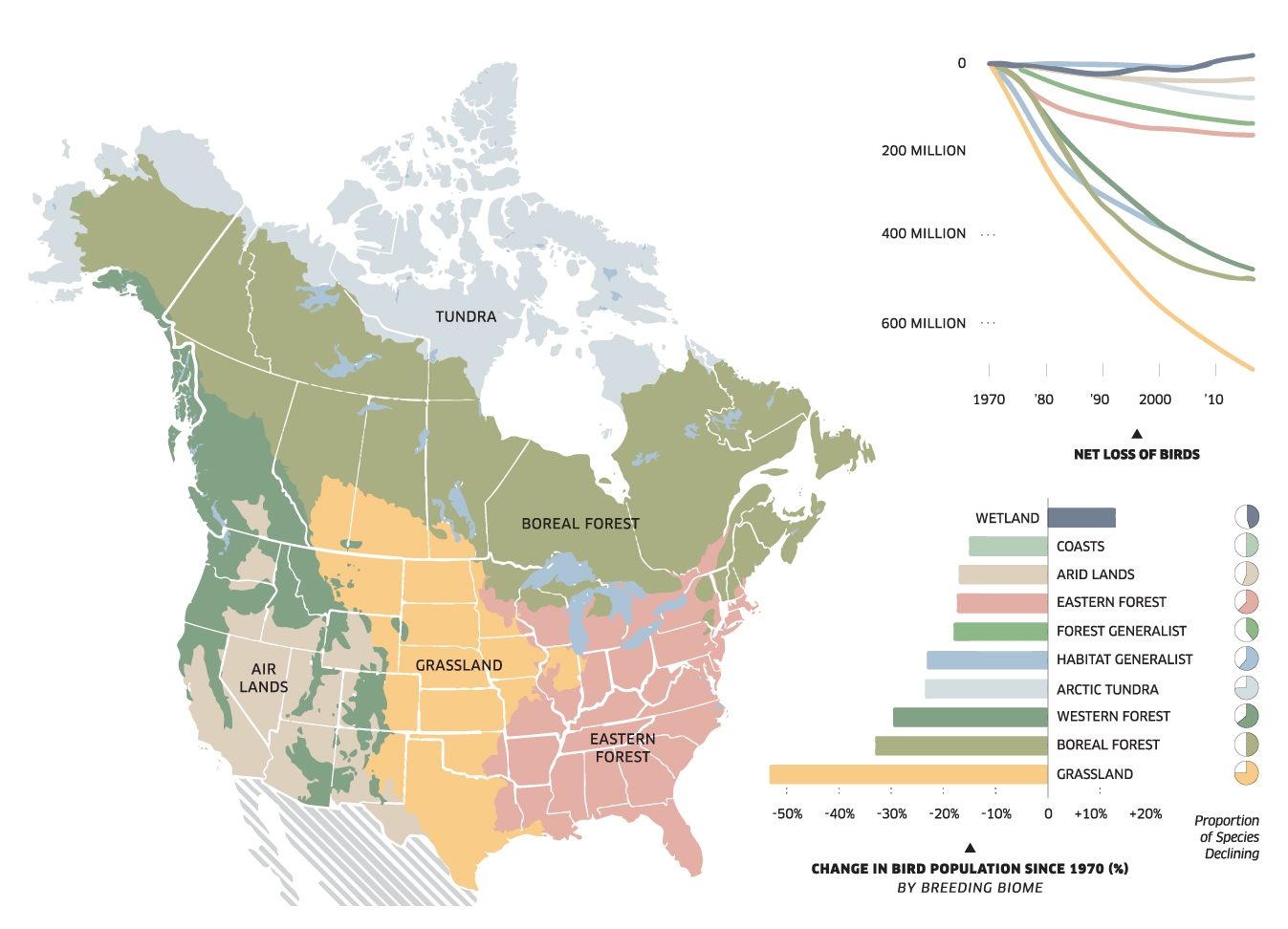

THE GREAT DISAPPEARANCE OF NORTH AMERICAN BIRDS

A survey of 529 bird species in the United States and Canada found that bird populations have fallen by 29 percent since 1970, a loss of nearly three billion birds.

A survey of 529 bird species in the United States and Canada found that bird populations have fallen by 29 percent since 1970, a loss of nearly three billion birds.

Source: science

After all, there is room for hope, with two of the nation’s most iconic success stories located right here on the Chesapeake.

At Patuxent’s Bird Banding Laboratory, circa 1920, biologist Jennifer Malpass and her colleagues keep all the bands that go out to the country’s 7,550 permitted banders, like Gruber and Gimpel, who altogether mark more than one million new birds each year, as approved by the Federal Migratory Bird Treaty Act. The world’s largest repository of banded bird data, they have more than 77 million banding records, stretching back nearly 100 years, and over five million encounter records, aka follow-up sightings from enthusiasts who capture the nine-digit codes in their binoculars or camera lenses, as well as from hunters who legally harvest waterfowl.

In these parts, it might sound contradictory, but waterfowl, such as ducks and Canada geese, are one of the few bird groups on the upswing, due in large part to the historic relationship between the BBL and the hunting community, which reports tens of thousands of encounters each winter, which then inform state and federal regulations, from harvest limits to hunting-season length. Hunters also pay annual fees, which contribute to habitat conservation. Nearly six million acres have been saved so far.

Raptors, too—bald eagles, ospreys, peregrine falcons—have dramatically rebounded since the 1970s, thanks to the ban of DDT, a once commonly used pesticide that pushed these birds of prey to the brink of extinction. Compared to 44 some 40 years ago, there are now at least 1,200 breeding pairs of our national bird throughout the state, with 200 or so nests monitored by volunteers of the Maryland Bird Conservation Partnership, which is also starting a similar program for barn owls and American kestrels.

“We may call them ‘our birds,’ but the reality is many other people across the country and world consider them their birds, too,” says the BBL’s Malpass. “It takes a whole village, and only by working together can we make a difference.”

CLOCKWISE, FROM Top LEFT: Birds are released back into the wild; the field office at work; birds awaiting their measurements; various bands.EDNA's plans.

CLOCKWISE, FROM Top LEFT: Birds are released back into the wild; the field office at work; birds awaiting their measurements; various bands.EDNA's plans.

CLOCKWISE, FROM Top LEFT: Birds are released back into the wild; the field office at work; birds awaiting their measurements; various bands.EDNA's plans.

CLOCKWISE, FROM Top LEFT: Birds are released back into the wild; the field office at work; birds awaiting their measurements; various bands.EDNA's plans.And over the next five years, Maryland will be home to a prime example of such community teamwork and citizen science with the Breeding Bird Atlas, the third-ever to be completed in Maryland and D.C. “It gives us a snapshot of how local populations are doing, and in quite good detail,” says Foley.

Like the BBS, present and past Atlases, like those completed in the 1980s and early 2000s, will inform the future, with the current iteration running through 2024, paying particular attention to the state’s 87 rare, threatened, or endangered species. But unlike the BBS, the Atlas is open to every skill level, and taking place across the entire state. “If you find a robin nesting in your backyard, you can report that,” says Foley, with observations submitted via Cornell’s eBird app or website. He expects more than 1,000 participants, seeing it as an easy way to get more young people involved in birding.

In 2020, the average birder is a white woman, aged 53 or older, with an above-average income. “Diversity is limited in bird-watching, but it’s certainly growing,” says Foley, citing newer groups such as the Feminist Bird Club and the Queer Birders of North America.

“WE MAY CALL THEM ‘OUR BIRDS,’ BUT THE REALITY IS MANY OTHER PEOPLE ACROSS THE COUNTRY AND WORLD THINK OF THEM AS THEIR BIRDS, TOO. IT TAKES A WHOLE VILLAGE.”

And from a small yellow brick rowhome on the edge of Highlandtown, the Patterson Park Audubon Center has been working toward that sort of inclusivity for decades.

“We want the future of conservation to look like Baltimore and we need to listen to these young people’s perspectives,” says center director Susie Creamer, who has helped create a green pipeline of sorts for the neighborhood’s large African-American and Hispanic communities, from pre-K nature programs through high-school camp counselor positions.

Their Embajadores de Aves, or Bird Ambassadors program, also teaches environmental education to Spanish-speaking adults who then implement local action plans, like street cleanups and habitat plantings, with many finding the a-ha moment in connecting the migrations of birds and people. “Both are traveling incredible distances and enduring many challenges to come to the U.S. and find a safe place to raise their families,” says Creamer.

The center hosts year-round community nature walks and native garden design workshops, too, even offering a special certifications for local residents and businesses who prioritize planting native plants throughout the city. Those species in particular have evolved complex relationships with birds up-and-down the food chain and through pollination over the centuries.

And by expanding and connecting these pockets of urban greenspace, the ultimate goal is to turn the city into a sort of oasis for birds—and Baltimoreans.

“It’s really for all of us,” says Creamer. “If the birds thrive, so do we.”

Editor’s Note: After publication, Maryland legislators banned the use of chlorpyrifos in 2021, the same year that the pesticide was banned by the EPA.