Travel & Outdoors

The Wonder of the Bay

What would we be without the Chesapeake? Maryland’s natural treasure remains a source of awe and wonder.

By Lydia Woolever

Spot Illustrations by Rose Wong

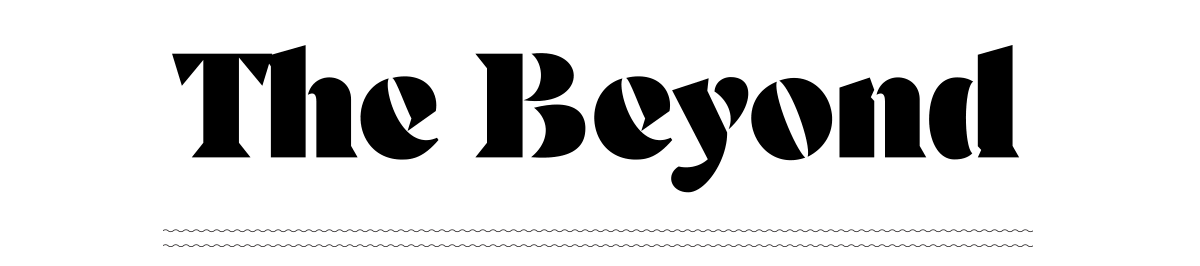

Opener: Photography By Cameron Davidson

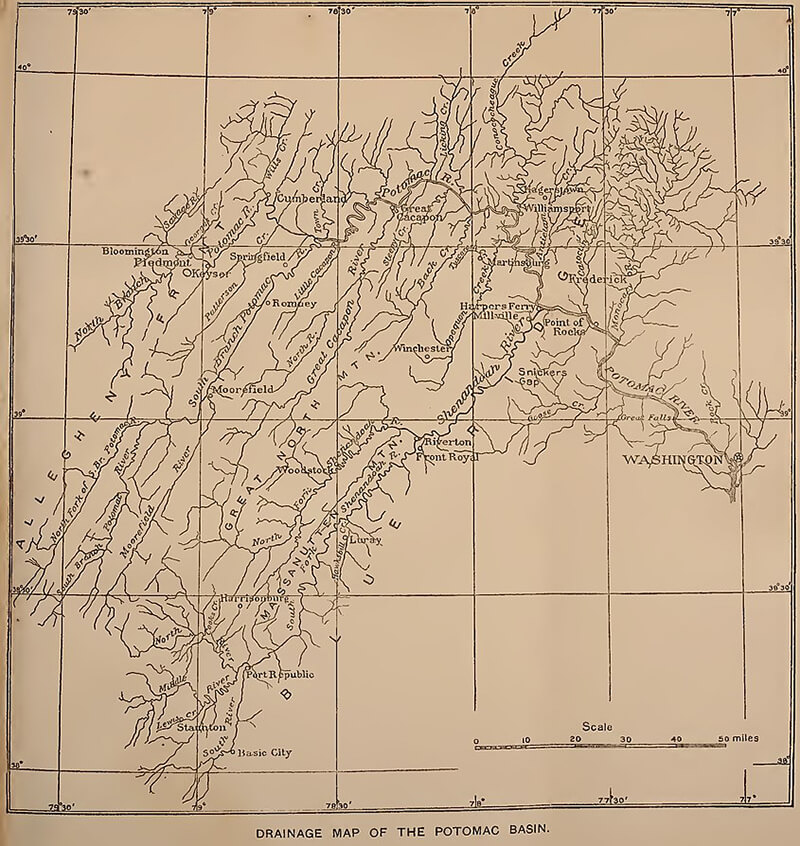

o anywhere in Maryland and you’ll find it. If you’re lucky, it’s within view or even reach. The old saying goes that if you live in the Old Line State, you’re never more than a few minutes from the Chesapeake Bay. And whether we know it or not, the nation’s largest estuary is all around us, flowing like arteries throughout this landscape. In the mountains of Western Maryland, small streams and creeks trickle south to larger tributaries, like the wide and majestic Potomac River, which cuts through our nation’s capital, then follows the western crag of Southern Maryland before heading out toward open water. In the central cities, like Baltimore and Annapolis, downtowns are designed around rippling harbors, and on the rural Eastern Shore, land slinks into rhythmic tidewater, as black-eyed Susan-clad signs that speckle the low-lying roadsides herald this place as “Chesapeake Country,” a nickname we could anoint the entire state.

In fact, in this region, nothing might connect us more—not crab cakes, not Old Bay, not the Orioles, not Natty Boh beer, all of which, one way or another, are also inspired by the Chesapeake. The Bay informs our history. It drives our industry. It fuels our economy. Whether you’re a waterman or sailor or seafood lover—or not—it inspires the way we eat, and play, and live.

It is the heartbeat of this place, and both literally and figuratively, we are entangled in it, with some 11,000 miles of shoreline crisscrossing not just Maryland, but beyond—from the Atlantic Ocean in Virginia to the Appalachian Mountains in West Virginia, through Delaware and Pennsylvania, up into upstate New York, where its 64,000 square-mile watershed begins.

Immense and immeasurable, “it is probably the most impressive body of water in the United States,” wrote Sun photographer A. Aubrey Bodine in 1954, which, we would argue, remains true to this day.

What would we be without the Chesapeake? Below, we’ll explore the ways this natural treasure has shaped who we are, turn to experts about the effects we’ve had, and endeavor to capture just a drop of the wonder that still moves us to save the Bay.

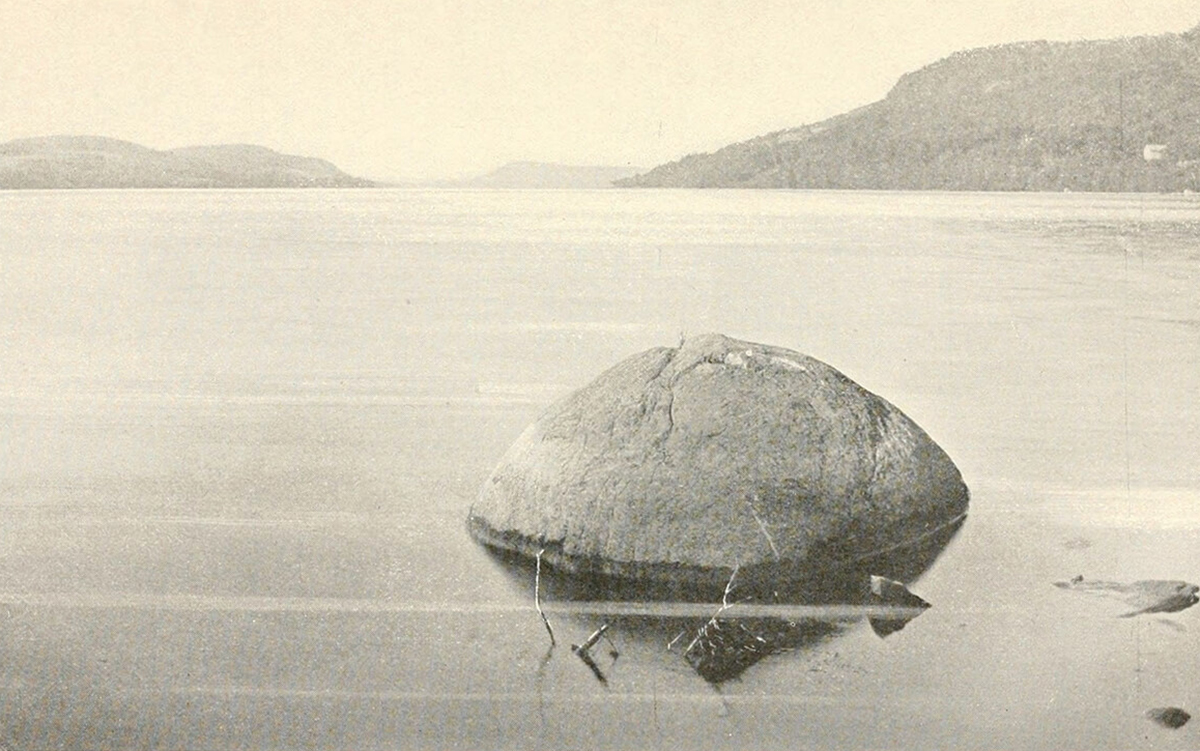

Council Rock on Otsego Lake at the headwaters of the Chesapeake Bay in upstate New York.—WIKIMEDIA COMMONS

FROM THE TOP

AT THE SOURCE

Let us begin with a lake in upstate New York.

y early November, most of the leaves have fallen from the trees on Otsego Lake along the foothills of the Catskill Mountains in Cooperstown, New York. Dappled in light, they float on clear waters, and with a slight breeze, flow south, past Council Rock—a small boulder sitting a stone’s throw from the shore, as old as the last ice age—then onwards, to the headwaters of the Susquehanna River.

It’s beautiful, sure, but also a bit anticlimactic. At the mouth of the lake, the mighty Susquehanna starts as a mere trickle—little more than a narrow stream that could comfortably be crossed with a rope swing—before gently wrapping beneath the village’s Main Street bridge and disappearing around a leafy bend. But eventually, it will snake its way a whopping 444 miles south, through fields, farms, and forests, towns and cities, becoming the longest river this side of the Mississippi, then dumping into its basin, the Chesapeake Bay. Five hours north of Baltimore, the birthplace of our estuary is where lake and river meet in the Empire State.

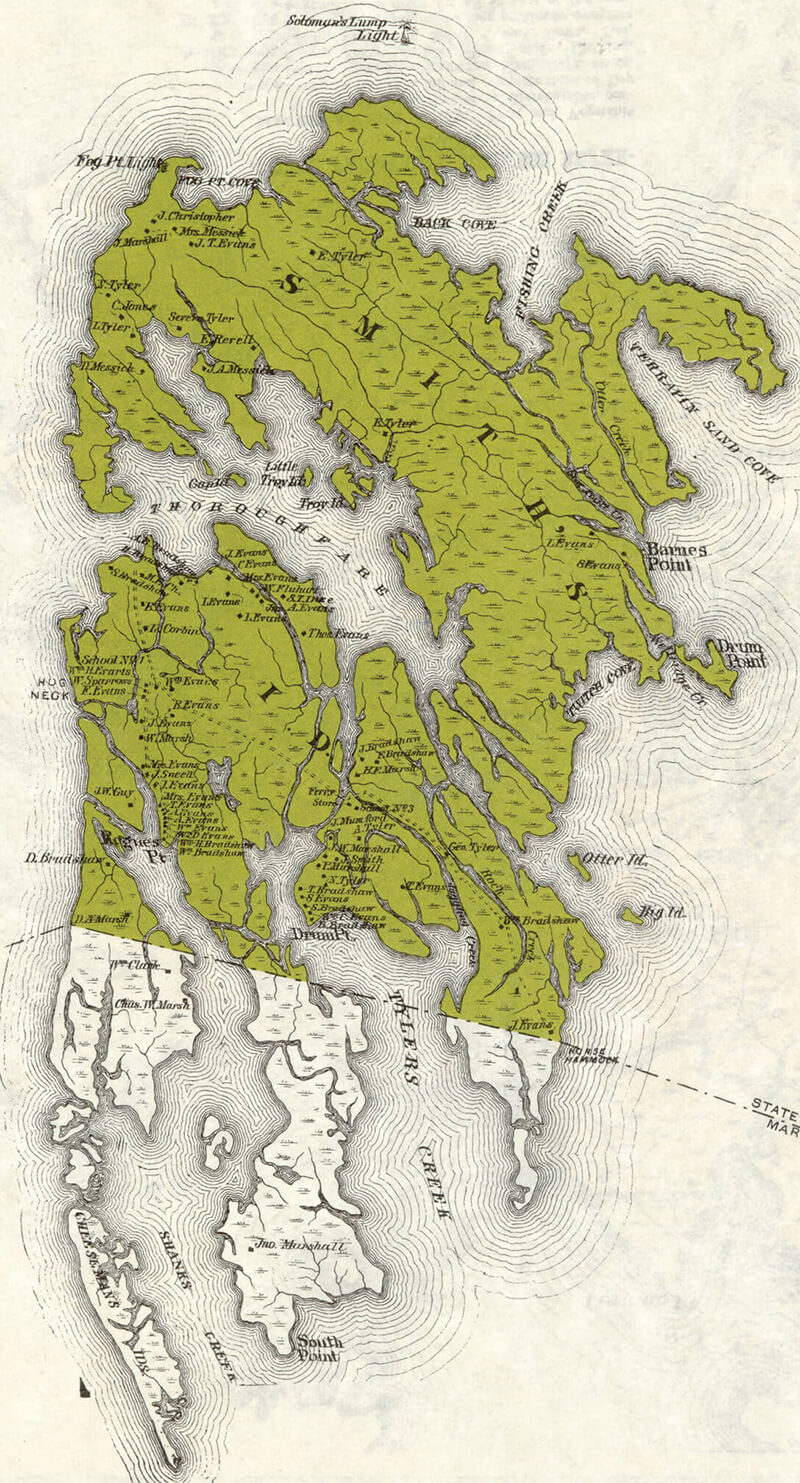

Of course, it’s easy for Marylanders to bristle at the thought of this, but the Chesapeake—Algonquian for “at a big river” or “mother of waters”—is not just the Bay proper, its broad waves speckled with white-sailed skipjacks and spanned by our state’s iconic Bay Bridge. Instead, it really is its watershed, aka the surrounding 64,000-square-mile landscape that covers six states, plus Washington, D.C., and is carved with a sprawling system of more than 100,000 streams, creeks, and rivers (known as tributaries) that provide half of its water.

A week later in Havre de Grace, many of those same ripples first spotted in upstate New York have now made their way to Maryland. Further south, they will become increasingly brackish—a mix of freshwater from the tributaries and saltwater from the Atlantic Ocean. Altogether, they will mingle into the 18 trillion gallons that fill our shorelines, with some heading further still, on out to the sea itself. It’s a millennia-old journey, dating back long before there ever was a Chesapeake.

THE HEADWATERS OF THE CHESAPEAKE IN NEW YORK, WHICH WILL ENTER MARYLAND IN A MATTER OF DAYS, BEFORE MAKING THEIR WAY TO THE OCEAN, OUR MAGNIFICENT BAY.

THE SUSQUEHANNA RIVER, CIRCA 1887.—WIKIMEDIA COMMONS

GEOLOGY

THE ORIGIN STORY

How glaciers, global warming, and one giant meteor helped create the Chesapeake.

long, long time ago. That’s when the Chesapeake Bay was born. And the number changes, depending on who you ask or how you look at it. Some say it’s 10,000 years ago, when this estuary—a body of water that blends rivers and oceans—first settled into its modern state. Others claim that it’s even older, dating to when the land first gave way to a wider and wider river valley—the predecessor of our present Bay. And few could argue, too, that it goes back further than that, to when the dinosaurs once reigned.

Whatever its birthday, the Bay’s formation is an epic and extraordinary story that sets the tone for its current magnitude. “We’re talking hundreds of millions of years,” says Richard Ortt, acting director of the Maryland Geological Survey. “Are you ready for a history lesson?”

ANCIENT OCEAN SHORELINE IN MARYLAND, CIRCA AT LEAST 12,000 YEARS AGO.—WIKIMEDIA COMMONS

Before there was an Atlantic Ocean, what we now think of as North America collided with North Africa as part of one colossal supercontinent, known as Pangea, and surrounded on all sides by open water. As those lands converged, immense pressure pushed the Earth’s crust upwards, creating what would eventually become the gentle rolling slopes of our modern Appalachian Mountains. Back then, though—about 200 million years ago—these ridgelines reached up as high as the Himalayas.

Over the epochs that followed, tectonic shifts caused the terrain to pull apart again, and those towering peaks eroded with it, their tippy-top sediments hauled east for a hundred miles to form the Atlantic Coastal Plain, on which we now sit. But picture this: our beaches ending not at Ocean City, but rather out on the edge of the continental shelf, where the land ended, the water still gets deep, and the early Atlantic originally began.

What did Maryland look like back then? “It changes through time,” says Carl Hobbs, geology professor emeritus at the Virginia Institute of Marine Science. Over the eons, swings between ice ages and global warming fluctuated sea levels by hundreds of feet. As glaciers melted, their runoff carved the ancestral Susquehanna River out of the land, and that over time, its valley would eventually become the Chesapeake. At times, too, a shallow ocean stretched west, filled with prehistoric sharks, whales, and sea turtles. Its waves came right up to the high-elevation “fall line”—think the Jones, Gwynns, and Gunpowder—that still cuts through the heart of Baltimore, which was then surrounded by tropical rainforest.

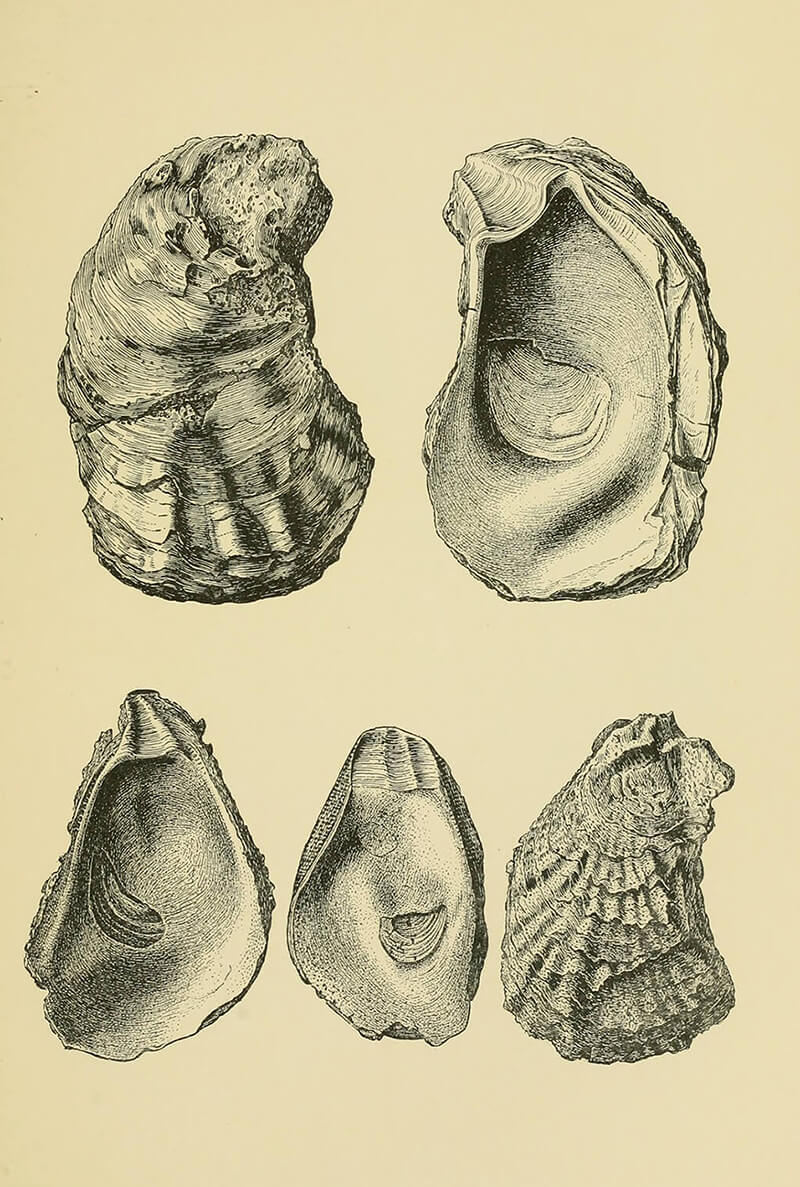

MIOCENE ERA SHELLS OF THE CHESAPEAKE BAY.-WIKIMEDIA COMMONS

But that all got interrupted 35 million years ago, when, in a twist of geological fate, a meteor struck off the coast of what we now know as southeast Virginia. As many as three miles wide, this celestial rock crashed into the region at a staggering 76,000 miles per hour, leaving behind a crater twice the size of Rhode Island and as deep as the Grand Canyon—“a hell of a hole,” says Hobbs, and still the largest known in the United States. A subsequent tsunami wiped out much of the life on land, though it wasn’t a total loss.

While the meteor did not technically make the Bay, as is often rumored, that cataclysmic impact would certainly influence its creation. Rivers flow downhill, so over time, the surrounding tributaries shifted their directions to convene at this new depression, near the future mouth of the Chesapeake. Before that, the Susquehanna had hooked a left and headed right out to the ocean, over what is now the Eastern Shore—no Bay required.

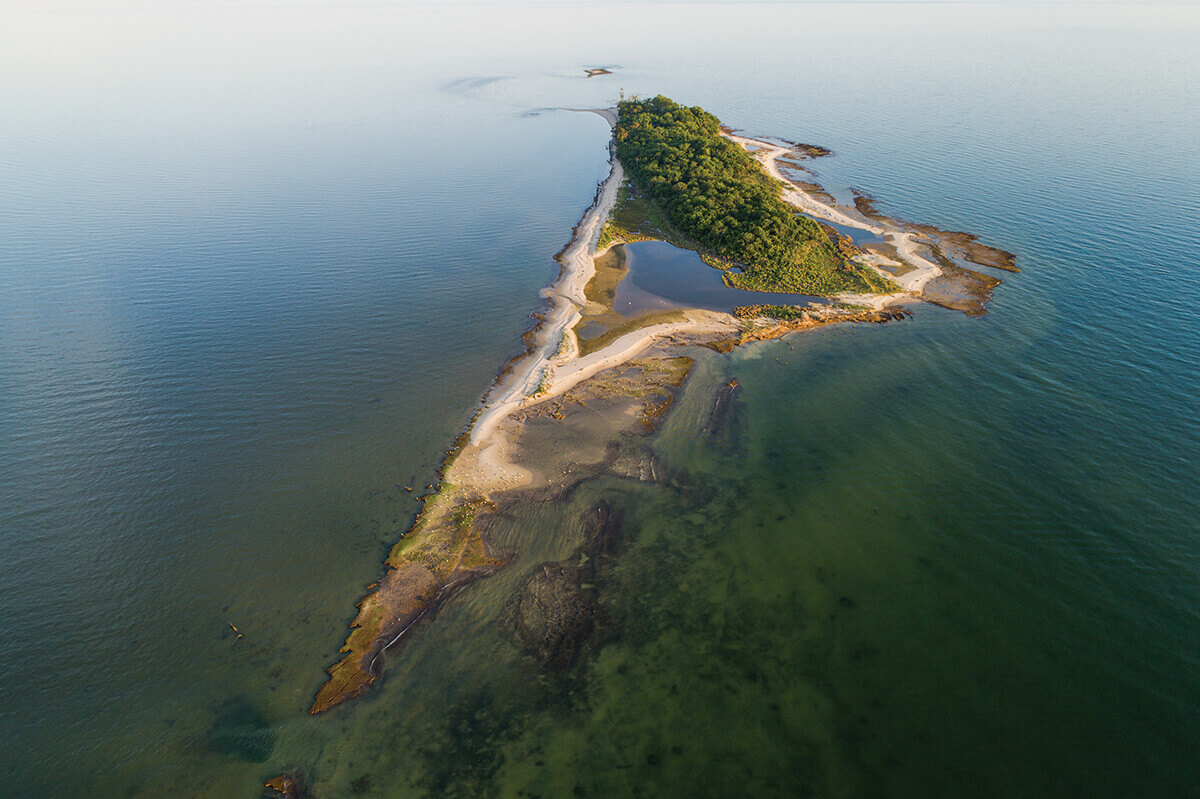

At that time, the Delmarva Peninsula didn’t exist yet. It would only show up over the last two million years, when glaciers sometimes reached as far south as Pennsylvania. Their mile-thick ice sheets pressed down on the Earth’s crust, once again pushing up sediment, which, over periods of rising seas, slowly sifted down the coast. Above the drowned Atlantic Coastal Plain, the Eastern Shore is essentially an ancient sandbar, sitting atop the long-lost crests of Appalachia.

In fact, it is ultimately the Shore that deserves credit for establishing the Chesapeake. Because without its 170-mile lowlands to both protect our state’s western edges from Atlantic waves and direct nearby tributaries towards its southern tip, an estuary might have never formed here. Who knows—Baltimore could have been a beach town, as up and down the western shore, “Those long rises of land that you can trace for hundreds of miles,” says Hobbs, “are old ocean shorelines.” Instead, we live between a quiet harbor and that looming fall line, where a supercontinent once stood, its enduring elevations now tumbling into tributaries toward the Bay.

And believe it or not, that big body of water is still changing. Glaciers continue to recede from some 20,000 years ago, and as the load has lightened on the Earth’s surface, parts of the Atlantic Coastal Plain slowly settle and, with the help of a warming climate and rising sea levels, begin to sink.

Always, too, there are currents, tides, winds, and rains that erode the land in one corner and deposit it in another. Old channels fill in. New sandbars curl out. And humans, of course, have an impact.

Today, the Chesapeake Bay proper is 200 miles long, ranging from three to 30 miles wide, with an average depth of only 21 feet. Below that bottom, traces of the old Susquehanna remain, its deep canyon slowly filled in with layers of time.

“Are we done?” says Ortt. “No. This is history. And the process is ongoing.”

It’s possible to commune with the past lifetimes of the Chesapeake. Just go stand at the edge of the Calvert Cliffs in Southern Maryland, and with enough luck, a relic might just reveal itself. An hour and a half south of Baltimore, along the Bay’s western shore, this ancient treasure trove spans 24 miles, notable not just for swimmable beaches but an abundance of fossils, sharks’ teeth, and seashells in its bluffs and along its strands, some as many as 18 million years old. During the Miocene Epoch, the region was a shallow sea, bound by tidal marshes, freshwater swamps, and bald cypress trees, not reaching land until modern-day Washington, D.C. Marine life was plentiful, and over the ages, their remains became buried under layer upon layer of sediment, being preserved for beachcombers like nine-year-old Molly Sampson, who discovered a palm-size Megalodon tooth this Christmas, or paleontologists of the nearby Calvert Marine Museum, where specimens from its 100,000-piece collection are regularly on display.

GET ON THE BAY

CAMP AT ELK NECK

At the top of the Bay, Elk Neck State Park sits on a spit of cliff straddled by open water and its namesake river in Cecil County on the Eastern Shore, with campsites that afford epic views down the estuary, plus a sandy beach and scenic lighthouse.

FLYFISH THE GUNPOWDER

Right in our own backyard, the Gunpowder River has long been heralded as an elite flyfishing grounds, beloved by the late Frederick native and famous fisherman Lefty Kreh Several stocked areas offer chances to catch-and-release brown and rainbow trout.

SAIL THE SEVERN

Hands down, the most iconic way to explore the Bay is by sailing along its waterways. In our state capital, hop on the Schooner Woodwind or Wilma Lee skipjack to see landmarks like the Annapolis harbor, watermen’s workboats, and the Bay Bridge.

PADDLE THE POCOMOKE

This lower Eastern Shore river, with its cypress swamps and flowering lily pads, is like a trip to the Louisiana Bayou. Float through the flora on a rented kayak from Snow Hill’s Pocomoke River Canoe Company.

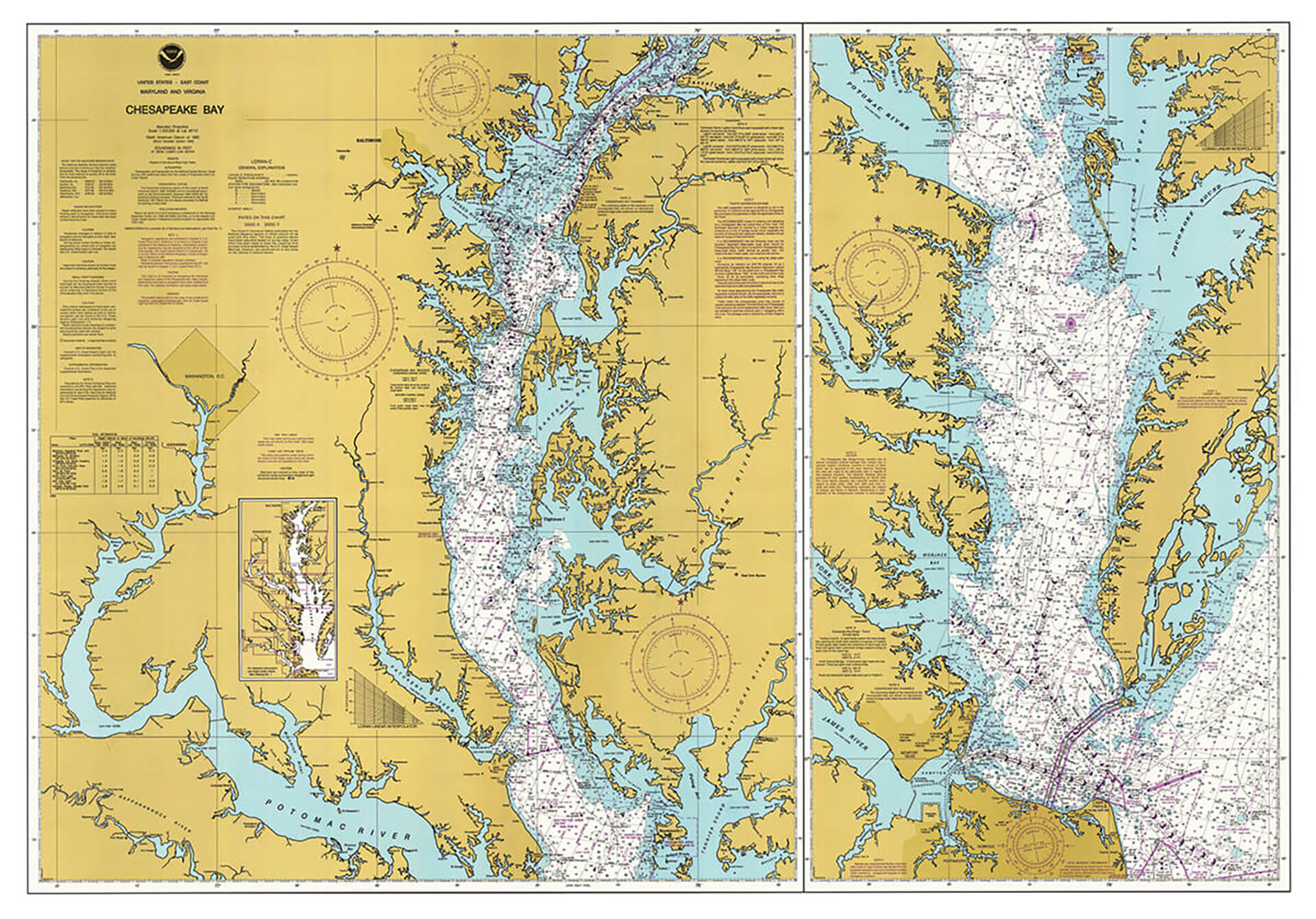

A NAUTICAL CHART OF THE CHESAPEAKE BAY. COURTESY OF THE NATIONAL OCEANIC AND ATMOSPHERIC ADMINISTRATION

NAVIGATION

There are some days when the Downtown Sailing Center keelboats can really feel the essence of our state nickname, the Land of Pleasant Living (allegedly invented by Natty Boh executives on top of the Bay Bridge in the 1950s). “Getting out past Fort McHenry, you’re able to look back and see all of Baltimore, and it really is pretty,” says Josh Johns, the nonprofit’s youth coordinator. But there are also other times when a wind kicks up or a storm rolls in and everything changes quickly. “I got caught in a microburst just past the Francis Scott Key Bridge,” says Johns. “It ripped my sails to shreds.”

The Chesapeake is often lauded with a sea of superlatives. Largest in the nation. Extraordinarily long. Especially shallow. Overflowing with marine life. But by its nature, it is also an estuary that defies categorization. Compared to the Gulf of Maine, its tides are modest, driven by the gravitational pull of the moon and the occasional downpour, swinging an average 1.4 feet each day in Baltimore. And because of its north-south orientation, “we get pretty strong wind influences on [local] sea level,” says Victoria Coles, oceanography professor at the University of Maryland Center for Environmental Sciences (UMCES), notably during hurricanes.

Those storms slip through the Bay’s narrow mouth, their gusts pushing up that huge volume of water, causing flooding along our shorelines. But even the right breeze can increase typically mild waves over its wide surface, becoming downright choppy. “On nice days, it’s very predictable—kind of low and slow moving,” says Christopher Paternostro, oceanographer at the National Atmosphere and Oceanographic Administration (NOAA). “But it can definitely get churned up.”

Luckily, the Bay’s craggy shoreline helps reduce some of that surf, usually to a property owner’s chagrin, and for boaters caught in nor’easters or summer squalls, its infinite edges can provide safe harbor, their shoals and sandbars leftover from that ancient Susquehannal carving of the estuary. Just navigate carefully—even if you run aground, the bottom is mostly sand and mud. “In most parts of the Bay, even out in exposed waters,” says Pete Lesher, an avid sailor and chief historian at the Chesapeake Bay Maritime Museum (CBMM) in St. Michaels, “you’re never terribly far from shore.”

A BLUE CRAB SWIMS UNDER WATER.—PHOTOGRAPHY BY JAY FLEMING

BIODIVERSITY

CRABS, OYSTERS, AND ROCKFISH—OH MY!

Part of a diverse and dynamic ecosystem, the estuary’s waterways abound with wildlife.

t the southern tip of North Point State Park in Edgemere, there is a thousand-foot fishing pier that juts out into the upper Chesapeake. With Baltimore City at your back, it’s hard to imagine that beneath the water’s surface, there exists another metropolis, just as vibrant and complex. Schools of fish stream north and south. Reptiles glide back and forth. Mollusks linger along the bottom, and a multitude of microbes drifts throughout like snowflakes.

From the freshwater streams of the watershed tributaries to the tidal marshes of the Bay’s middle to its saltwater mouth at the Atlantic Ocean, more than 3,000 species of flora and fauna live across the myriad environments of this estuary. There are those we know well—the holy trinity of blue crabs, oysters, and striped bass (that’s rockfish to locals)—as well as some 300 other types of fish, 170 other types of shellfish, dolphins, Diamondback terrapins, otters, and, of course, jellyfish—the Bay being home to its own unique kind. There’s even the occasional seahorse. Not to mention the rest of the life, from white-tailed and wild turkey to beavers and black bear, that lives on land.

“Estuaries are really cool places because they are so dynamic,” says Sean Corson, director of NOAA’s Chesapeake Bay Office. “You’ve got these huge rivers with huge pulses of freshwater draining huge watersheds into this quite shallow body of water with a narrow mouth, making it a very productive environment that supports a huge range of species.” In fact, ecosystems like the Chesapeake are some of the most biologically productive on the planet. And their physical features play a pivotal role.

It’s been said that a six-foot man could walk much of the Bay without getting the top of his head wet—24 percent, to be exact. That shallow depth allows light to permeate the water and, through photosynthesis, essentially feed phytoplankton, which work their way up the food chain. Varying salinities create ideal conditions for a variety of species, from freshwater and saltwater specialists to brackish in-betweeners. There are those who migrate in for certain seasons and others who live here year-round. “In the summer, we have cownose rays that come from Cape Hatteras,” says Matthew Ogburn, senior scientist at the Smithsonian Environmental Research Center (SERC) in Edgewater. “And in the winter, species like herring and shad make their way from Long Island or the Gulf of Maine.” And with the help of wind and rain, the surrounding watershed seeps nutrients from the landscape, which, at the right levels, help the wildlife survive—and flourish.

Indeed, “The Bay is so large and has so many connections,” says Dave Secor, marine biology professor at UMCES, “which is a key reason why it’s so diverse.”

As one might expect, the wildlife itself is also interacts constantly. Take oysters, for instance. These immobile mollusks filter phytoplankton from the water and provide habitat for small fish like menhaden. Those tiny foragers are an important food source for rockfish, but themselves feed on the likes of zooplankton, which include baby blue crab larvae. Later, those adult crustaceans will, in turn, eat oysters and even other crabs, before being devoured by birds, bigger fish, and humans, who dine on the bivalves and rockfish, too. Oyster reefs also help dampen waves that cause erosion, thus protecting our shorelines. And, with their water-cleaning abilities, they create more hospitable growing conditions for underwater grasses, which, in full circle, provide protection for their predators.

On the whole, the Bay is full of delicate balances, and both big and small shifts can have significant ripple effects across the ecosystem. Could local declines in menhaden be causing the drop in rockfish populations? Is the rise of invasive blue catfish influencing historic lows for crabs? Will warming water temperatures push more species like flounder out of the estuary? Where do new species fit in, like the Carolina shrimp now moving up the Bay? And what will it mean for the Chesapeake’s resilience to climate change? Only time will tell.

“At a really broad scale, the most biodiverse places are further south, with the most being the tropics and the least being the poles,” says Ogburn. “In theory, biodiversity might actually be increasing. But it means big changes over time.”

WILDLIFE

Behold, feathers in flight!

Aquatic creatures aren’t the only stars of the Chesapeake. For some, birds get top billing here, with both wildlife lovers and waterfowl hunters alike flocking to observe their abundances in the heart of the Atlantic Flyway, while locals mark the seasons by their migrations. In the spring, ospreys, eagles, and both green and great blue herons are common sights along our shorelines. Come winter, hundreds of ducks, geese, tundra swans, and snowy egrets descend upon the waterways, arriving from as far north as the upper reaches of Canada. But of course, there’s nothing more miraculous than spotting a Baltimore oriole, found along local riverbanks in summertime.

If you throw a fishing line enough times in the Bay these days, the odds are likely that, before long, you’re going to haul up a trespasser. The blue catfish is the biggest culprit, with an estimated 100 million of them now living in the estuary, even though they don’t belong here. Thanks to human error, these whiskered bottom-feeders were introduced in Virginia for recreational angling in the 1970s, spreading vigorously and becoming a voracious new predator for baby crabs, juvenile rockfish, and lots of other native species, disrupting our natural ecosystems. But they’re not the only ones; the newly infamous snakehead—sharp-toothed and able to walk on land—is just one of the Bay’s 200-some invasives. But fortunately, humans can help. Those two, at least, are edible and increasingly found on local restaurant menus. And guess what? They actually taste good. Save the Bay by eating them.

TASTE THE BAY

NATIONAL HARD CRAB DERBY

Forget Preakness—for 76 years, the hottest race in Maryland has taken place on Labor Day Weekend in Crisfield, once dubbed the “crab capital of the world.” In peak Eastern Shore fashion, come see which crustacean can scuttle the fastest. Stay for the crab picking, crab cooking, and Miss Crab Claw contests.

U.S. OYSTER FESTIVAL

Some of Baltimore’s best seafood slingers bring their bivalve skills to this festival’s national shucking competition. At the St. Mary’s Fairgrounds in Southern Maryland on the third weekend of October, swing by the tasting tent to slurp shooters and half-shells grown in nearby waters.

NATIONAL MUSKRAT FESTIVAL

What a little water-loving rodent for such a wildly polarizing Chesapeake creature. In February, cast your squirminess aside, when a Dorchester County middle school transforms into the state celebration of all things muskrat, with wild-game tastings, world-championship skinning contests, and pageants where the winners take home fur sashes.

THE SPRING SHAD RUN ON THE POTOMAC RIVER, CIRCA 1950.—PHOTOGRAPHY BY A. AUBREY BODINE

AT RISK

On the verge of collapse, some of our once-famous species get a second chance.

For a long time, it was the rite of spring—fishermen crowding the river’s edge in wait for the annual shad run, when millions of silvery slivers returned from the ocean to their native tribtuaries to spawn. Latin for the “most delicious,” these rich bony fish were coveted for both their buttery flesh, typically smoked over cedar planks, and their luxurious roe, considered a delicacy.

“Our heart goes out in pity to those luckless Americans who know nothing of the Chesapeake shad,” wrote H.L. Mencken in a 1907 Sun, which at the time seemed like an unthinkable possibility. After all, this was the Bay’s first commercial fishery, a staple food for Native Americans, and the “savior” that fed George Washington’s troops during the American Revolution, but the Baltimore Bard’s words would prove alarmingly prescient.

By 1980, Maryland shuttered its shad season, those once-abundant populations having plummeted to historic lows due to overharvest, pollution, and, perhaps biggest of all, the addition of dams like the Conowingo. Those blocked the migrations of myriad species, including herring, sturgeon, and eel, with consequences up and down the food chain.

But restoration efforts are now underway across the state, including on the Patapsco River in Baltimore. Three major dams have been removed, and scientists are now waiting to see whether the fins return. “It’s been a challenge,” says SERC’s Ogburn, who’s leading such studies, “but we’ve seen some fish moving upstream.”

SCENES OF NATIVE AMERICANS IN CHESAPEAKE VIRGINIA, CIRCA 1590. COURTESY OF THE MARINERS' MUSEUM

PEOPLE

A WORLD OF WATER

The first Marylanders lived close to the land and tides.

ust 20 miles north of the Maryland line, surrounded by a wide flat vista of Pennsylvania forest, a series of island-like boulders rise from the middle of the Susquehanna River. At certain times of day, when the tide recedes, a series of etchings reveal themselves—petroglyphs of people, animals, spirits—and tell an ancient story of this tributary.

“Human habitation in the Chesapeake Bay region goes back a long time,” says CBMM’s Lesher, “before the Chesapeake Bay even existed.”

Indeed, Native Americans arrived in this region more than 10,000 years ago, during the end of the last ice age, when the estuary was just a dry sweep of land along the ancestral Susquehanna. Small bands evolved into more than 40 tribes, always following the waters and their ample food sources—first with inland tributaries, then, as temperatures warmed, the widening Bay. Archaeologists have found their millennia-old oyster shell piles along the Potomac, near Annapolis, and on the Eastern Shore, and their handcrafted fishing traps inform the modern trotlines and pound nets we still use to thiday. When Europeans showed up in the 1600s, many Indigenous communities helped the settlers survive, but new disease, colonial conflict, and forced exile led to their dramatic declines.

Still, more than 40,000 Marylanders identify as at least part Native American today, with three tribes—the Piscataway Conoy, Piscataway Indian Nation, and Accohannock—officially recognized by the state, though others also remain. (The Lumbee also now reside in Baltimore, having migrated from North Carolina in recent decades.) And their influence is all around us, from the roads we travel, to the names of our towns and waterways (Patapsco is Algonquian for “backwater”), to sacred sites across the estuary.

“We have been here, we are the people of the Chesapeake,” says Piscataway Conoy tribal chairman Francis Gray, whose ancestral lands extend along the Western Shore, from the Patapsco River in Baltimore County through Southern Maryland, where his people work with the National Park Service, NOAA, and regional waterkeeper associations on local environmental projects. “In our worldview, the Bay is a living entity.”

DEVELOPMENT

The city was built on the back of its marshy basin.

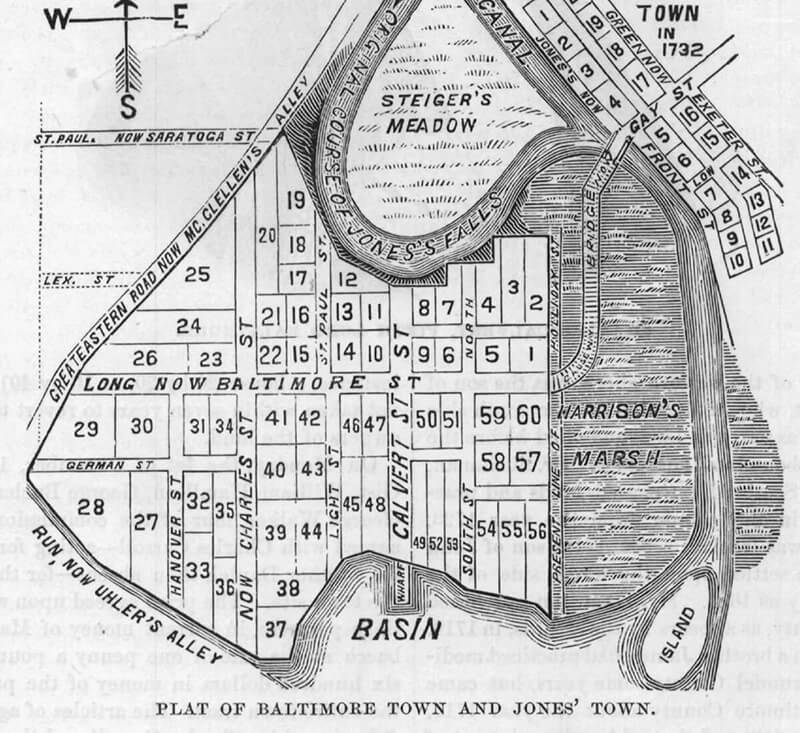

EARLY PLAT OF BALTIMORE TOWN AND JONES TOWN.—WIKIMEDIA COMMONS

When Baltimore Museum of Industry visitors ask how the city came to be, senior docent Jack Burkert knows the answer: “I take them to the window and point to the harbor . . . it begins here.” In 1661, an English Quaker named David Jones built the first farm in the region, just north of a marshy basin off the Patapsco River—on a plot of land and along a winding stream that would both eventually take his name (Jonestown and the Jones Falls, respectively). Before long, other settlers were drawn to those fertile soils and fine forests, and by 1729, Baltimore Town was established as a future tobacco port. It never quite became one, but over the centuries, a booming hub did develop around its waterfront, starting with the deepest docks in Fells Point. From Woodberry to Curtis Bay, neighborhoods fanned out along the waterways, founded on industries that were forged by the harbor and fueled by immigrants whose port of entry was the Chesapeake. “Looking at old maps, you can see the city grow in this concentric circle, bigger and bigger, out from the harbor,” says historian Johns Hopkins (no relation) of the nonprofit Baltimore Heritage (BH). “But the oldest part remains right there.”

In the summer of 1608, Captain John Smith launched a small sloop from Virginia’s Jamestown and started to make his way up the Chesapeake. The English explorer was in search of precious metals and a passage to the Pacific Ocean, part of his home country’s quest to capture a viable colony in the “New World.” Instead, through storms, seasickness, and a near-death by stingray, he found a different kind of gold mine: “the most pleasant place ever known” with “large and pleasant navigable rivers” where “heaven and earth never agreed better to frame a place for man’s habitation” along a “fair bay, compassed but for the mouth, with fruitful and delightsome land.” While historians have since questioned some of Smith’s details (like that run-in with Pocahontas), his records would inspire others to explore, and then colonize, this estuary, shaping where we live today. A complicated character, indeed, but he offers us a peek into the Bay that once was—as well as old Baltimore. His noted “bank of red clay” would eventually become Federal Hill.

Trace the lines of any Chesapeake skipjack and you’ll follow the shape of water. Maryland’s state boat is part of a long lineage of local watercraft that were built for this particular estuary. Like log canoes, pungies, bugeyes, and even Baltimore clippers before them, their shallow hulls were made for the shoals of our tidal waterways. Simple sails were fit for both our mild winds and smaller crews, so more energy could be spent, say, fending off the British or harvesting oysters. Materials hailed from nearby natural resources, like white oak and yellow pine forests, while some designs and techniques dated back to Indigenous shipwrights.

Before roads, boats were our Buicks, used for everything from carrying cargo to just getting from A to B. And up and down the Bay, a few of the region’s once-prolific boatyards still exist, like the Patuxent Small Craft Center on Solomons in Southern Maryland, or the Chesapeake Bay Maritime Museum, where they just finished a replica of the Maryland Dove that belonged to Lord Baltimore. In Baltimore, head to the harbor to watch canvas unfurl when the Sigsee, Constellation, and Pride leave their slips. And any time you cross over the Bay Bridge, know that those iconic deadrise workboats are a hat-tip to their predecessors, with some of the same graceful curves riding the waves as they have for centuries.

SUMMER LOG CANOE RACES ON THE MILES RIVER.

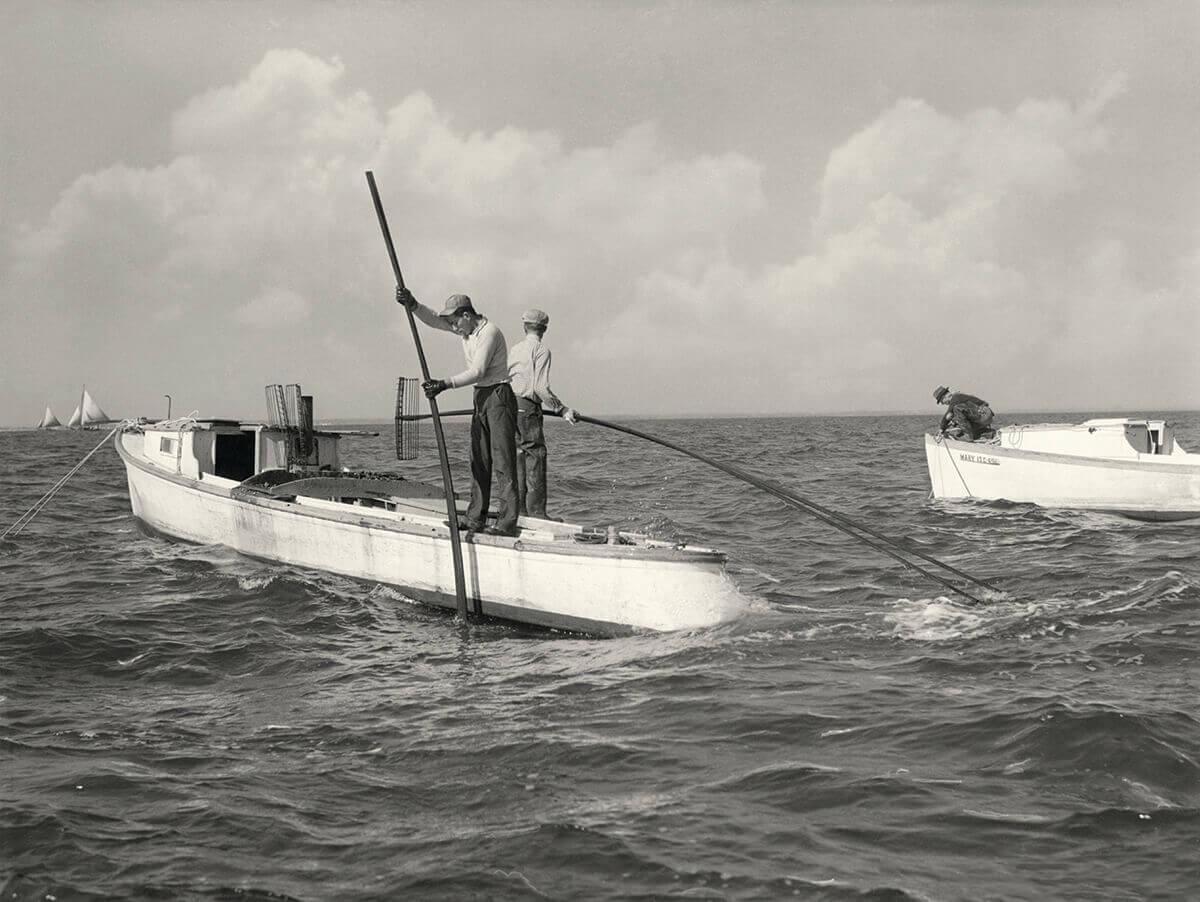

OYSTER TONGING ON THE BAY, CIRCA 1950.—PHOTOGRAPHY BY A. AUBREY BODINE

ECONOMY

THE AGE OF INDUSTRY

An estuary that could launch a thousand ships—and then some.

riving along the Jones Falls Expressway, motorists often forget that the once-rushing stream of its namesake is now buried beneath them. And not just any stream, but a 17-mile tributary so significant that it can be credited with the transformation, if not creation, of Baltimore.

Before it was a bona fide boomtown, the city was just a sleepy backwater with a struggling tobacco trade, with economic success felt further south, on the plantations of the Eastern Shore and Southern Maryland. That is, until the 1750s, when Scottish colonist John Stevenson got the grand idea to sell a different crop that actually liked the local landscape. He packed up a few bushels of wheat, bid it goodbye down the swampy harbor, and the rest is history.

Dozens of water-driven gristmills soon scrambled to that old geological highline—the Jones and Gwynns Falls, as well as along the Patapsco River—and Baltimore flour made Maryland the “breadbasket of the American Revolution.” “That was the city’s first big success,” says Baltimore Heritage’s Hopkins. From there, “Our harbor became busier and busier, then people start sending all sorts of stuff out of it.”

Of course, to move that merchandise, we needed ships, and Fells Point’s first shipyard heeded the call. Soon, other boat-building operations lined the waterfront, with wharves and warehouses rising to meet demand, launching the city’s second industry. Ironworks forged anchors. Fiber factories twisted hemp into rope. And as agriculture diversified, those old mills turned to flax, then cotton, making Baltimore the nation’s largest maker of “duck canvas,” aka sails. The Chesapeake was now a maritime Mecca, and the city’s eventual clipper ships can be credited with winning the War of 1812, thus saving America.

It was around this same time that we also began using boats to hungrily harvest the Bay’s finest export: seafood. Inspired by a growing population, watermen took to the then-prodigious oyster reefs—once solely used for local sustenance and so large they were navigational hazards—then sold their catch through Baltimore. Some of it traveled on ice via the B&O Railroad, but for better shelf life, with the advent of steam, the city’s first cannery opened in 1849, followed—like shipyards—by a hundred others, gaining the town its reputation as “Oyster City.” In the off-season, they packed produce—sweet corn, tomatoes, peaches—sailed in from the Eastern Shore. “Waterways were the highways,” says the BMI’s Burkert. “We had ships that went in every direction in and out Baltimore.”

Fittingly, too, those cans were made of steel manufactured just down the harbor, at Sparrows Point. The freshly dredged shipping channel launched another new era, with deep-sea vessels pouring into Bethlehem Steel and the Port of Baltimore, which remains the ninth most valuable in the country.

Over the years, the Bay’s industry has evolved—exit tinned fish, enter recreation and tourism—but the estuary endures as an economic powerhouse. Fisheries still bring in $300 million annually, while restoration-related projects create thousands of jobs. And in Baltimore, one particularly sweet vestige hangs on today. By the late 19th century, sugar refineries speckled the harbor, says Hopkins. “You can still watch the big old ships, coming and going with Domino.”

FOODWAYS

The patron saint of Chesapeake cuisine, chef John Shields shares a few fond memories.

If we only had one word to describe the Bay’s terroir, that would be easy: brackish. Mencken referred to this slightly salty place as “the great protein factory,” and aquatic ingredients are undoubtedly the heart and soul of our local foodways, much as they always have been. But few chefs champion that bounty quite like John Shields of Gertrude’s Chesapeake Kitchen. Since 1998, he’s kept first-rate fried oysters and classic crab soup flowing in Baltimore, though the 71-year-old Parkville native has spent a lifetime loving the Bay’s seafood.

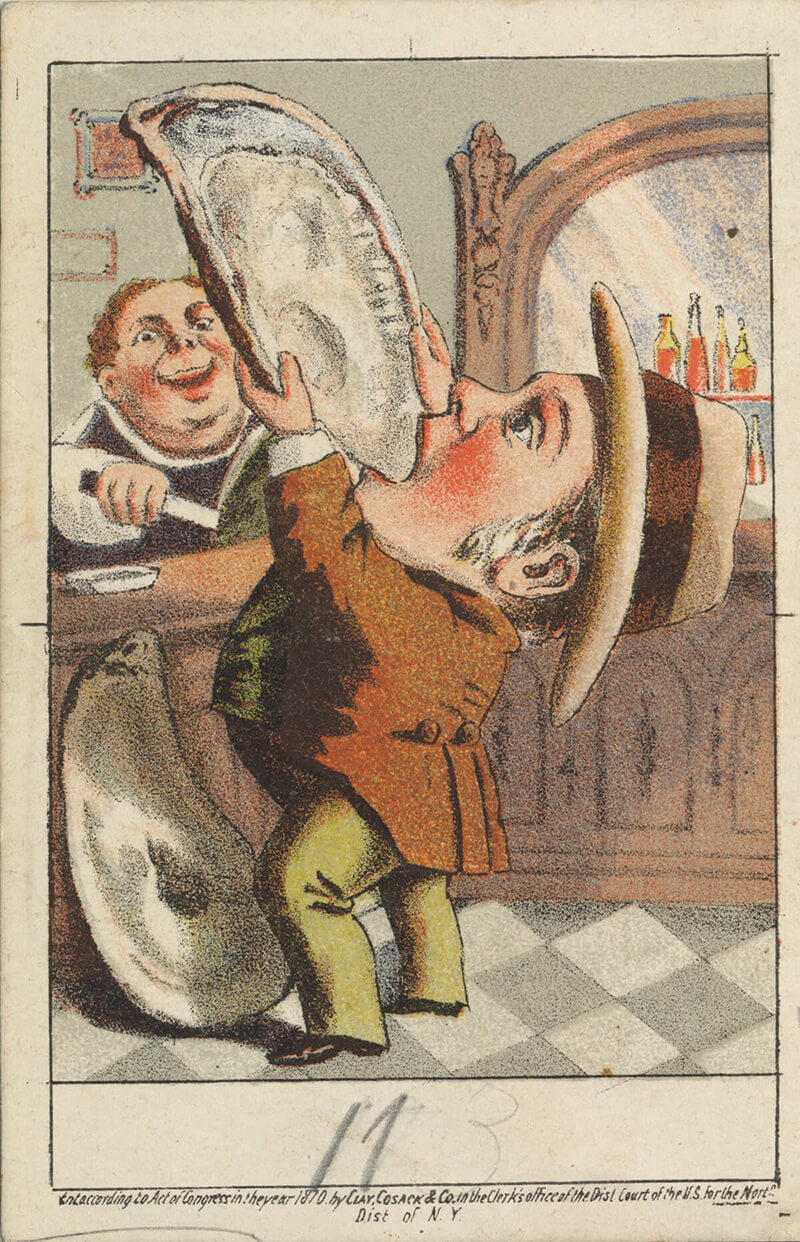

AN 1870 OYSTER ADVERTISEMENT. COURTESY OF THE NATIONAL MUSEUM OF AMERICAN HISTORY

On public markets:

“These days, we have ‘sexy’

seafood, but back in the day, it

was pan-fry fish. Perch, herring—like Herring Run! We lived

here in Baltimore and there

were so many wonderful fishmongers.

North Avenue Market.

Cross Street. And of course,

Faidley’s at Lexington.”

On the best striped bass:

“One of my favorite things, my

grandmother, Gertie, would

make once or twice a month

during the season, typically

when the relatives went fishing

and brought home a beautiful

rockfish. She’d butter a baking pan, slice in some onions,

take the whole fish, wrap it in

bacon from the German

butcher down the street, put

it in the pan, then pour local

milk in the bottom. It would

roast and steam all at the

same time. It was so good,

but also so simple.”

On beginner bivalves:

“Growing up, I had a pretty

working-class upbringing. I

remember some of my father’s

friends would come

home after working a night

shift, grab us kids, and take

us to the corner bar. For

breakfast, they’d get platters

of oysters and glasses of

locally brewed beer. I remember

thinking that was the

coolest thing. Way better

than my oatmeal.”

There is a place on the upper Eastern Shore where fields lead to forests that turn to bluffs that tumble into the tranquil Sassafras River, and if you arrive too late after the autumn equinox, it will smell like sweet garbage. Weeks prior, this pawpaw grove hung heavy with the perfectly ripe version of North America’s largest native fruit—dusty green, the size of your palm, soft to the touch, like a naked avocado. Until recently, such wild orchards were one of the watershed’s best-kept secrets, with only multi-generation fans and master foragers knowing exactly where to find them. But once you’ve studied their smooth trunks and sizable leaves, you realize: They’re everywhere, and always near local streams and riverbeds. Maryland is one of the pawpaw’s 26 home states, and that custardy pulp is now making its way onto regional menus—a fleeting delicacy usually served in the shape of jams, pies, and ice creams. Long before that, though, they were a common food for Native American communities, Lewis and Clark expeditions, and African Americans on the Underground Railroad. That first taste should involve cracking one open, grabbing a spoon, and eating it raw. Just catch them before they fall—and ferment. At that point, they’re raccoon food.